The Art of Reconciliation

Sometimes, challenging the idea that there is one official version of Canada’s past is handled best by artists rather than academics. Drawing on his Cree roots, art history, and a deep well of both rage and humour, Kent Monkman has created clever, beautiful, unsettling works that force us to re-examine what we think we know.

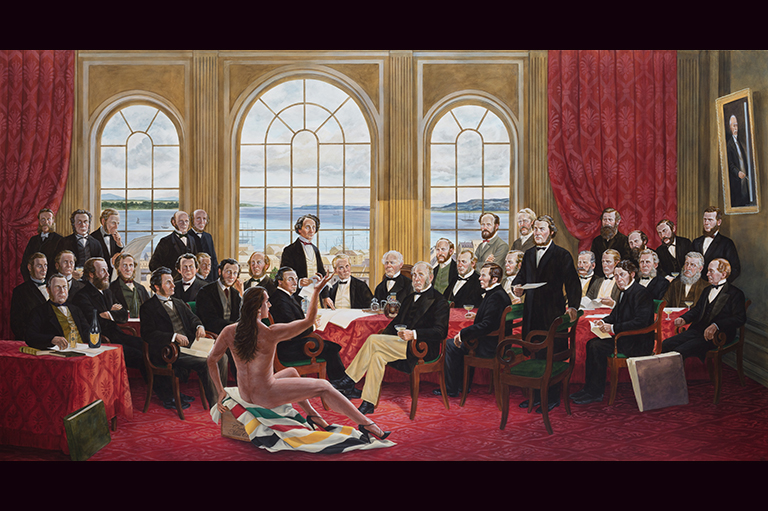

Monkman’s gender-bending time-traveller (his description) Miss Chief Eagle Testickle pops up in the past, present and future to jar viewers out of complacency. Picture the famous Robert Harris painting of the Fathers of Confederation. Monkman’s version features the same men in the same setting, but with a naked Miss Chief posing or perhaps holding forth in front of them. In this version, called ”The Daddies,” many of the august gentlemen are holding or eyeing booze, evoking the famous observation that “Confederation was floated through on champagne.”

Monkman’s work combines Indigenous symbolism, classical technique and historical reality to create an unflinching look at colonialism’s devastating impacts. In “Struggle for Balance”, men on a residential street help—or rape?—a Picassoesque woman while a car burns and an Indigenous woman sits with a baby on her lap. From the skies, a bald eagle and tattooed angels out of Caravaggio look on. Despair, hope, love and violence collide, unresolved.

Painful and joyful in almost equal measure, “Reincarceration” depicts emaciated wooden figures emerging from a distant residential school, wading into water and emerging on the other side to become fully human as they dance around a fire.

In one installation, a long table is laid for a feast, with fancy canapes, china, crystal and silver. At the far end are a few plates on rough boards scattered with bones of small animals. The piece, which highlights the impact of the end of the fur trade on Indigenous people, is titled “Starvation Plates”.

The brightly painted “The Scream” shows Mounties, priests and a nun ripping Indigenous children from their families—perhaps to take them to residential schools, perhaps as part of the Sixties scoop. The Mounties are nearly identical, with pale faces and short hair. They betray little emotion while the children and their parents scream and weep in anguish.

This is not a painting to glance at and walk by. It is a painting that enters the bloodstream and floods the heart. On the black walls to left and right are rows of neatly organized spaces; a few filled with beautifully carved or beaded cradleboards, others with institutional metal frames, and others simply bearing grim outlines resembling nothing more than small coffins.

This is art that steps in where impersonal, “official” history falters. It makes us wiser and more vulnerable, taking us to a place where understanding, and then healing, may just be possible.

Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Reconciliation runs from January 26 to March 4, 2017, at The Art Museum at the University of Toronto, after which it will tour across Canada as part of sesquicentennial celebrations.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement