Reclaiming Saint Kateri

On April 17, 1680, a young unmarried woman died in a little settlement on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. She was a Mohawk. As a child she had suffered from smallpox, and its ravages left her with permanent scars. In the last few years of her short life, she had become a devout Christian.

That much is agreed upon. The rest is open to debate.

In the eyes of Roman Catholics, the woman born with the name Tekakwitha is now Saint Kateri. Pope Benedict canonized her in a ceremony at the Vatican in 2012. Yet, long before her canonization, Kateri — an Aboriginal version of Catherine, the name she chose when she converted to Christianity — had been the object of intense devotion.

To Catholics, her readiness to suffer without complaint, her self-willed virginity, her fierce love of the sacraments — such qualities prove that she lived out her faith in an exemplary manner. According to the Jesuit missionaries who were near her at the end, she told her friends to “Take courage” and “Never give up mortification.” She lost the world and found herself in God.

Many Mohawks, especially those who adhere to the Longhouse traditions, see things very differently. In their eyes, Tekakwitha was a victim of colonialism. Having abandoned her own community, she cast her lot with the French invaders of her people’s land. The French instilled in her a foreign religion that promoted ideals contrary to those of the Iroquois Confederacy, to which the Mohawks belonged. After she died, her image was used by the church to help stamp out Iroquois culture and to promote a vision of assimilation that remains alive to this day. In this Mohawk view, her life is to be regretted, not held up as a model.

Such is the division of opinion about Kateri Tekakwitha. In the Mohawk town of Kahnawake, where some of her remains lie in an imposing church near the St. Lawrence River, Kateri is one more source of discord in a remarkable community — one that is full of strong, tough, successful people but is all too familiar with bitter differences. The Jesuits hoped she would become a rallying symbol. She has proved to be anything but.

And yet, in the past few years, another view has begun to emerge — a view that suggests a way forward, a chance to understand Kateri beyond the ruptures of belief.

“I think of her as a storyteller,” said Orenda Boucher-Curotte, standing on a street in Kahnawake near Kateri School, just down the road from the Kateri Memorial Hospital Centre. “She’s our window into women’s lives in that particular period. What were the women facing? What kind of experiences were they having?”

Boucher-Curotte attended Kateri School when it was Catholic-run; now it’s non-denominational. She earned a master of arts in the history and philosophy of religion from Concordia University and is studying for a Ph.D. at the University of Ottawa. She notes that the early texts about Kateri were written not just from a European standpoint but from a male one, too. “Yet we know,” she said, “women were integral to the survival of that society. What interests me are the relationships she cultivated, before and after she came here. How can we reread her story, understanding it from a Mohawk world view?”

The way the tale usually goes, Tekakwitha was the daughter of a Mohawk chief and an Algonquin woman who had been captured and absorbed into Mohawk society. They lived in what is now upstate New York, in a village whose spelling has gone down in history as Caughnawaga (“by the rapids” in the Mohawk language). The mid-seventeenth century was a period of great turbulence, with societies and nations dissolving and reshaping themselves as European weapons, diseases, and beliefs swept over eastern North America. A smallpox epidemic left Tekakwitha an orphan, facially scarred and with poor sight. At four she was adopted by an uncle on her father’s side.

Or was she? Boucher-Curotte is not so sure. “The story doesn’t make sense to me. She should have gone with her mother’s brother. The Jesuits may have confused the kinship ties — they don’t talk about her mother. I’m curious about all the things the Jesuits left out. Why did they leave them out?”

Missionaries were active in Caughnawaga, and Kateri was baptized at the age of twenty, on Easter Sunday, 1676. That fall she travelled north to the Jesuit mission on the St. Lawrence to live in the company of other converts. The community was founded as a refuge for “praying Indians.” The mission was located east of present-day Kahnawake; it moved to its present location, across the river from the Lachine Rapids, early in the eighteenth century. Kateri lived only three years at the mission, spending much of her time in acts of fasting and extreme penance.

“Jesus, I love you,” she said, before expiring in the arms of a female friend. Then, as the Jesuit priest Pierre Cholenec wrote, “This face, so marked and swarthy, suddenly changed about a quarter of an hour after her death, and became in a moment so beautiful and so white that I observed it immediately.” To the faithful, this was Kateri’s first miracle. She became known as “Lily of the Mohawks” forever linked to a white flower that connotes chastity, purity, and innocence. The lily was also a royal emblem of France and would eventually be a symbol of Quebec. Today, in the Catholic church at Kahnawake — named after the first Jesuit missionary to Asia, Saint Francis Xavier — her tomb has a carved lily.

Cholenec’s story has been hugely influential. Yet, by describing Kateri’s natural skin colour as “swarthy” and by associating beauty with whiteness, the priest created a troubling image for Aboriginal people. Before she was canonized, Kateri was beatified — a preliminary step on the ladder of sainthood. Maybe it’s just a spelling mistake, maybe it’s a Freudian slip, but a booklet about Kateri that is still available in the gift shop of the Saint Francis Xavier Mission at Kahnawake declares that, in 1884, the bishops of the United States asked Pope Leo XIII “to institute the process for the beautification of Catherine Tekakwitha.” To the church she was indeed beautiful, once death had whitened her skin.

Darren Bonaparte, a Mohawk historian from Akwesasne, titled his 2009 book about Kateri “A Lily Among Thorns.” For him the phrase not only refers to the Old Testament verse in the Song of Solomon but also suggests how Kateri’s people are too often viewed. Bonaparte set out to reclaim Kateri as a Mohawk woman. “It’s as if she has always been a porcelain icon,” he wrote. “Her memory has been so thoroughly appropriated that even her own people speak of her in terms taken verbatim from the writings of others. For a nation that has laboured for the repatriation of human remains, wampum belts, false face masks, and other significant items held by museums and universities, we seem to have neglected something just as important —the memory of one of our own.”

Today, Kahnawake, in addition to its Catholic church, has three flourishing longhouses where traditional spirituality is practised. The community also contains three small Protestant churches. Yet, through nearly all of the Kahnawake’s long history, the dominant world view was Catholic. Akwiranò:ron Martin Loft, the supervisor of public programs at the Kanien’kehá:ka Onkwawén:na Raotitióhkwa Language and Cultural Centre, grew up at the end of that era. “We used to go to the church for baptism, first communion, catechism,” he recalled, “and Kateri’s bones were on display. When we were children we used to kneel there and look down at the bones. Her image was there in the background. We had to kiss the glass and then wipe it clean with a little cloth for the next person.”

Only a few of Kateri’s bones are still in Kahnawake. As her fame grew, the church distributed relics as far afield as Montana, South Dakota, and the Vatican. Her skull went to Akwesasne, where it disappeared in a fire. A theft of one of her bones from the church in Kahnawake means that only a small replica is now on show. Such are the risks of sanctity.

“When I arrived here,” said Ron Boyer, “I’d say the reservation was ninety-eight per cent Catholic.” Boyer is an Ojibway man from northern Ontario who, as he jokes, “was kidnapped by the Mohawks. My wife’s a Mohawk, and she always says, “We’re not fussy who we adopt.’” They settled in Kahnawake in 1957 and are among the small minority of Kahnawake residents who remain devout Catholics. Indeed, Boyer is an ordained deacon and spent seven years as the “vice-postulator” for Kateri Tekakwitha, building a case for her to be canonized. Meanwhile, the Vatican awaited a miracle clear enough for the already beatified Kateri to step into sainthood.

The miracle arrived with news of a six-year-old boy in Washington state, Jake Finkbonner, who had contracted flesh-eating disease through a cut on his lip. The bacteria spread quickly, the last rites were performed, and the boy’s life hung by a thread. But Jake’s father, a member of the Coast Salish nation, had heard stories of Kateri when he was young, and, at the urging of the parish priest, the family prayed to Kateri. A Mohawk nun who was a family friend visited Jake in hospital and placed a tiny relic of Kateri on his leg. Inexplicably the boy recovered, though his face will always be scarred. Soon Ron Boyer’s work was complete.

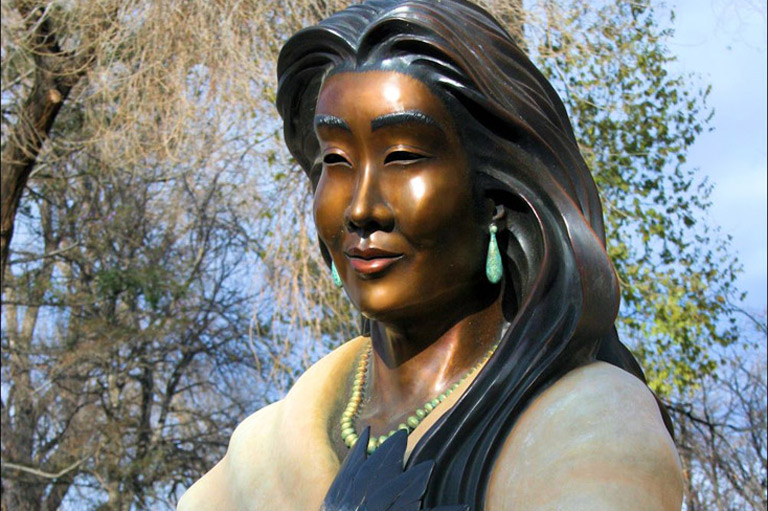

One thing this story reveals is the extent to which devotion to Kateri has spread all over North America — and, indeed, farther south. On the day she was canonized in Rome, the church in Kahnawake held a large service, and Orenda Boucher-Curotte recalls meeting a woman who had flown in from Guatemala. “Kateri Circles” for American Indians exist in about twenty-five American states; at the Mission Dolores in San Francisco, where Spanish Franciscans established the first white settlement in the region, a statue of Kateri stands in the garden. In New York City, a bas relief of Kateri decorates the main doors of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. For Aboriginal Catholics everywhere, she remains a powerful symbol.

But a symbol of what, exactly? “Catherine Tekakwitha,” says the narrator of Leonard Cohen’s novel Beautiful Losers, “I have come to rescue you from the Jesuits.” Cohen was writing in the mid-1960s, when there was “a plastic reproduction of your little body on the dashboard of every Montreal taxi.” Now the power of the Catholic Church in the province has receded dramatically, and the meanings of Kateri’s suffering and death are in dispute. In most of Quebec, her name is still recognized, but her story seems to belong to a distant, priest-ridden past. Yet vestiges of that past remain. Boucher-Curotte points out that, at the Kahnawake service in 2012 celebrating the canonization, a priest referred to the non-Christian Mohawks of Kateri’s time as “heretics.”

When Martin Loft thinks of Kateri now, his mind dwells on subjects far removed from the faith of his boyhood. “It’s an incredible story,” he said. “It’s tragic. It’s uplifting, if you’re a believer. And, generally, people are proud that it makes us a well-known community. But you wonder about the legacy of residential schools, the abuses the people had to suffer, all the things that were done to ingrain Christianity in us. That’s part of the colonial legacy we have, and you could argue she’s a symbol of that.” He stops and catches himself. “You have to be careful what you say. You don’t want to offend people.”

Over the past year or so, Ron Boyer declares, Kateri’s canonization has brought a “very noticeable” increase in visitors. Other people aren’t so sure — and they don’t necessarily think it would be good if crowds of pilgrims began descending on Kahnawake.

“I’m surprised, and pleasantly so,” said Brian Deer, a respected elder and Longhouse member, “that there wasn’t more hullabaloo about her canonization.” Sure, hundreds of visitors came to Kahnawake when she was sainted and many residents of Kahnawake made a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Rome for the occasion. “But, after that weekend, I didn’t notice an influx of tourists. What I feared the most was that Quebec province would hijack her for tourist purposes — but it didn’t happen.”

Deer said Kateri is “not on the radar” for most people in Kahnawake today. She is seldom talked about, except for an occasional negative remark made by people who are hostile to the church. Admittedly, her name remains prominent. But just because the school and the hospital have Kateri in their title doesn’t mean people stop to think about the saint every time they go there.

Steve Bonspiel, the editor and publisher of the Eastern Door,Kahnawake’s main newspaper, agrees with Boyer that “there’s been an increase of tour buses. I live near the church, and I pass by them every day. But the problem is, the church in Kahnawake doesn’t have any money, and they don’t want to spend anything for fear of not getting the returns.” In a community of about eight thousand residents, only about sixty people regularly attend Mass. The church no longer has a resident priest, and the dwindling number of parishioners struggle to pay an annual heating bill of roughly $25,000.

Unlike Brian Deer, Bonspiel hopes that Kahnawake will become a welcoming destination for tourists: “Pilgrims are coming here all the time, and they have nowhere to go. Even the people who aren’t Catholics know that we’re not going to stop them [from] coming here. At the end of the day, if they can find places to eat or hang out, the community would benefit.”

His motives for saying this are not purely economic. Bonspiel wants to break down some of the barriers that separate Kahnawake from the rest of society. “There’s still a prejudice,” he noted, “that Mohawks act in a certain way.” It’s less than twenty-five years since residents of the nearby town of Châteauguay infuriated by the Oka crisis, burned a Mohawk warrior in effigy. Some francophones still casually refer to Aboriginal people as “les sauvages.” If the church’s museum and gift shop were upgraded, and if local restaurants and cafes attracted more visitors, would outsiders begin to see Kahnawake more clearly?

Cross-cultural interaction is one of the things Kateri Tekakwitha did well. As an adolescent, despite her weak sight, she moved successfully from one community to another, impressing and finally humbling the black-robed priests she met along the way. “She was something other than a victim,” said Allan Greer, a historian at McGill University and the author of Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits, the standard academic work on the subject. “In my classes I present her as someone of a Mohawk culture who was pursuing Mohawk priorities.”

And what might those be? Greer, sipping a coffee in a west end Montreal cafe, looks slightly uncomfortable at being pressed. “I have misgivings about my own vocabulary,” he confessed before saying: “Spiritual power. In a situation of crisis and turmoil, which is what indigenous people were experiencing in the seventeenth century, they were pursuing not just survival but empowerment — which necessarily has a spiritual dimension. There’s almost a curiosity-driven exploration. People often think of the Jesuits as being heroic explorers of foreign lands — and that’s what she was, too. She was confronting the question: How do you figure out these strange people and their strange ways?”

Kateri was steeped in traditional religion as well as in Catholicism. For centuries, that duality of knowledge was very difficult to attain. Yet today, said Kahente Horn-Miller, the coordinator of the Kahnawake Legislative Coordinating Committee, “the distinctions — Longhouse, Protestant, Catholic — are not as strongly drawn as they were. I go to the church for funerals, I’ve been to the midnight Mass for the singing, and I know of other Longhouse people who do the same. My aunt is a devout Catholic, and she goes to the Longhouse as well as the church.” A generation or two ago, Longhouse people and Catholics in Kahnawake were never allowed to socialize. The lines are fuzzier now.

Orenda Boucher-Curotte, who also grew up in a Longhouse family, said that, for decades after the church’s influence had waned in Kahnawake, “men wouldn’t talk about Kateri, and women would roll their eyes. She didn’t represent what it meant to be a Mohawk woman. Motherhood is a central part of our culture, and she forsook that. The Jesuits always pointed out how different she was from the other converts. That’s one of the qualities of sainthood — they have to be different. But the reality is, she couldn’t have survived for twenty years after her parents died without being part of a community.”

Likewise, Kahente Horn-Miller suggested that different parts of Kateri’s story speak to different elements in the community. The miracle stories may not seem to resonate for Horn-Miller, yet Kateri’s “relics were used to heal others,” she said. “And, likewise, we have our ceremonies, our herbs, our rituals, our traditions. Those are areas where I can identify with her. I identify with her wanting to practise her religion, too.” Eventually such perceptions may allow more of the Longhouse adherents in Kahnawake to forgive Kateri her sainthood.

On a summer morning, Boucher-Curotte and I stroll around the Saint Francis Xavier Mission. She grew up attending a longhouse and, unlike most of the older generation, has seldom been inside the ornate church. We pass stations of the cross that have Mohawk names and carved prayers in the Mohawk language. But, in the church gift shop, a local volunteer named Cathy Rice shows less interest in talking about Kateri than about a 1907 bridge disaster in Quebec City that claimed the lives of seventy-five people, thirty-three of them from Kahnawake.

Near the front of the church stands a cross made of steel from the World Trade Center in New York; it was donated by Mohawk ironworkers after the terrorist attacks of 2001. Men from Kahnawake helped construct many of New York’s iconic skyscrapers. They took little part, however, in building the St. Lawrence Seaway in the late 1950s; the project meant that about five hundred hectares of Mohawk land were expropriated, and Kahnawake was cut off from the great river. Across the road from the church, a cenotaph honours the dead of several conflicts, including the War of 1812. Memories are long here, and Kateri is only the beginning.

A second volunteer emerges from a back room of the museum attached to the church. She is carrying an oval case with a narrow rib bone inside. “I took it out of the safe for you,” she explains. The label says, in French, “bone of Catherine Tekakwitha.” I hold the case in my hands. Orenda Boucher-Curotte is looking as surprised as I am. And a moment of visceral understanding comes to me: Kateri lived and died down the river from where I’m standing now. She became a symbol only because she once had a body. This small curved bone helped her live and breathe.

A saint, perhaps. A Mohawk woman, beyond doubt. I take a deep breath of my own and give back the oval case.

For more about Kateri’s remarkable life and legacy, see this video hosted by Father Thomas Rosica.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement