Solving the Franklin Mystery

One summer day in the not-too-distant future, off King William Island in the High Arctic, scuba divers from Parks Canada will swim into the cabin on HMS Terror that Captain Francis Crozier once occupied.

Working carefully in freezing-cold water roughly twenty-three metres below the surface, these underwater archaeologists will search drawers and shelves, systematically gathering artifacts until — eureka! — they come upon an array of rusty metal cylinders or canisters.

Controlling their excitement, they will place these items in a specially designed lifting bag and bring them topside. Judging from past experience, only when they have delivered this cache to their colleagues will they give themselves over to the extraordinary rush of having entered history.

Almost certainly, the canisters will contain written records from the 1845 Franklin expedition, whose leadership Crozier inherited. Almost certainly, they will reveal answers to the greatest mystery of Arctic exploration: What happened to that expedition?

This year marks the 175th anniversary of the departure from England in May 1845 of the vessels HMS Erebus and HMS Terror.

Former warships newly fitted out with heating systems, reinforced hulls, and steam engines for use when the winds failed, the vessels sailed from Greenhithe (thirty-five kilometres south of London) with enough food to last three years. Under Sir John Franklin, the expedition was expected to locate and to travel through the long-sought Northwest Passage across the top of North America and to emerge into the Pacific Ocean trailing clouds of glory.

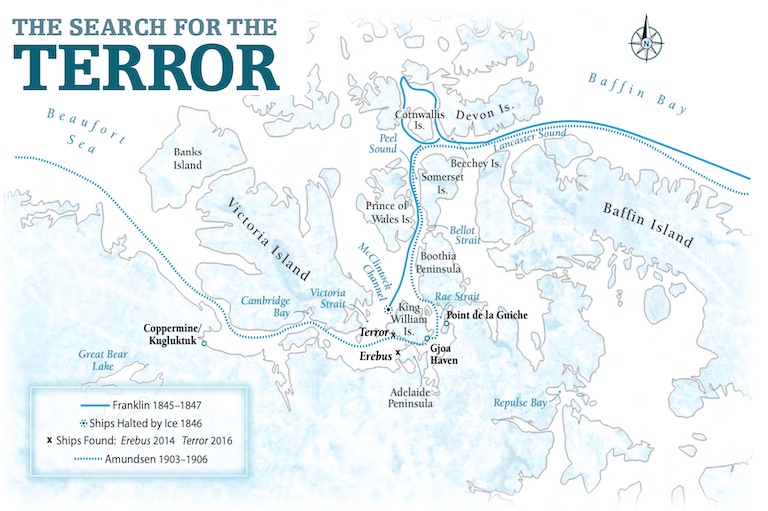

Those ships, as many readers will know, ended up half-way through the passage at the bottom of the sea. Canadian searchers located the wreck of the Erebus in 2014 and that of the Terror two years later.

Since those discoveries, Parks Canada divers have been investigating the two ships whenever Arctic conditions permit — usually for a week or ten days in late July or August. From the Erebus, just eleven metres below the surface, they have brought up dozens of relics, among them the ship’s bell.

In August 2019, during an exceptional seven-day calm, investigators got a first extended look at the wreck of the Terror.

They dropped a remotely operated vehicle, an ROV, through a hatch on the ship’s upper deck and steered it around to explore twenty compartments on a single deck. In a statement released by Parks Canada, underwater archaeologist Ryan Harris — who operated the ROV — said the Terror is so well-preserved that it looks like “a ship only recently deserted by its crew, seemingly forgotten by the passage of time.”

The video he captured shows china plates and bottles still stacked on shelves, weapons still standing in their racks, and officers’ cabins looking neat, trim, and ready for inspection.

Underwater archaeology manager Marc-André Bernier was especially struck by the pristine condition of Crozier’s cabin, which greatly surpassed the team’s expectations.

“Not only are the furniture and cabinets in place,” he said, “drawers are closed and many are buried in silt, encapsulating objects and documents in the best possible conditions for their survival. Each drawer and other enclosed space will be a treasure trove of unprecedented information on the fate of the Franklin expedition.” A buildup of sediment blocked access to Crozier’s sleeping quarters, which obviously cry out for inspection.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Back in 2017, while sailing in the Northwest Passage as a resource historian with Adventure Canada, I caught a presentation by Bernier. Speaking generally about the two Franklin ships, he flatly declared: “I expect to find human remains.

Most likely bones, skeletons.” Bernier reminded his listeners that Inuit testimony speaks of at least one body on what would appear to be the Erebus, and he added that he had seen flesh on bones before. “If sedimented, the remains could be very well preserved.” He cited the example of a wreck from 1770, HMS Swift, which researchers located in Patagonia: “They found a complete skeleton in uniform.”

While Bernier showed slides about the Parks Canada search, we sailed into a blizzard. As our ship, the Ocean Endeavour, heaved and rolled, some of us shuddered to think about facing such conditions in a small wooden ship.

And we found ourselves doing a quick calculation. The Endeavour is no multi-storey cruise ship, but it is still more than four times as long as HMS Erebus (137 metres to 32) and more than twice as wide (21 metres to 9). The Terror was smaller still.

The storm raged unabated into late afternoon. When Bernier finished presenting, he hurried up onto the bridge to confer. He had been planning to lead a visit to the site of the Erebus, where some of us would go snorkelling. But, with the swell reaching 1.5 metres, the wind gusting to gale force (upwards of fifty knots), and the Endeavour needing to navigate a narrow channel (0.3 to 0.6 nautical miles) to reach the site, the undertaking was clearly in jeopardy.

At the evening briefing, Bernier and Adventure Canada’s expedition leader, Matthew J. Swan, relayed the bad news. We would not be visiting the Erebus site after all.

Swan said the thought of putting Zodiacs into the water when the winds were blowing at more than 25 knots ... sending out passengers on a forty-minute Zodiac ride each way ... no, he couldn’t see it: “The Zodiacs would just flip.”

Bernier revealed that several Inuit guardians had established a five-tent campsite on an island near the wreck, but, he said, “three of those tents have blown off.”

Bernier regretfully rejected the idea that maybe we could wait out the storm where we were. Speaking from experience, he said these wind-and-wave conditions would already have stirred up sediment so badly that at best the wreck would become visible in three days.

And, if the storm continued, we might have to wait a week. Swan could only shake his head: “We’re disappointed, of course. But we’re motivated. We’ll try again next year.”

So they did. But not until two years later, on its sixth attempt, did Adventure Canada get voyagers to the site of the Erebus. There was no snorkelling, but passengers did travel by Zodiac through choppy waters to a Parks Canada barge positioned above the wreck, where they met archaeologists and Inuit guardians and watched real-time video of divers at work below.

Ushered into an artifacts lab on the barge, the visitors studied newly discovered objects, among them a ceramic bottle, leather boot sole, a glass decanter, and tiny tongs that may once have been used for sugar cubes.

Travel writer Jennifer Bain wrote later that, “Looking at these ancient objects transports us back to 1845, when Franklin and his men set sail from England on two ships, convinced they would find the fabled Northwest Passage.”

What happened to that expedition? Starting with the sailing from England in May 1845, the prevailing British narrative of the Franklin mystery tracks the final letters sent from the ships in July 1845 and moves through the discovery in 1850 of three graves on Beechey Island.

Those graves showed that Franklin had wintered on Beechey in 1845–46, but an intensive search of the island begun by Scottish whaling captain William Penny and American explorer Elisha Kent Kane turned up no indication of where the two ships had gone from there.

Subsequent search expeditions sent by the Royal Navy, the Hudson’s Bay Company — whose charter stipulated exploration — and Jane, Lady Franklin (widow of Sir John) produced no significant findings until 1854, when the Inuit made the first of many crucial contributions to discovering what came to be summarized as “the fate of Franklin.”

In April of that year, on the west coast of Boothia Peninsula, an Inuk named In-nook-poo-zhe-jook revealed to HBC explorer John Rae that the Franklin expedition had ended in catastrophe.

With the help of William Ouligbuck Jr., the finest Inuit interpreter of the era, Rae interviewed In-nook-poo-zhe-jook and more than a dozen other Inuit. They told him that a ship had sunk off the west coast of King William Island; that thirty-five or forty starving sailors had straggled south along that coast; and that some of the final survivors had been driven to cannibalism.

These revelations sparked an extraordinary backlash, with no less a figure than Charles Dickens writing two long screeds denouncing Rae and the Inuit.

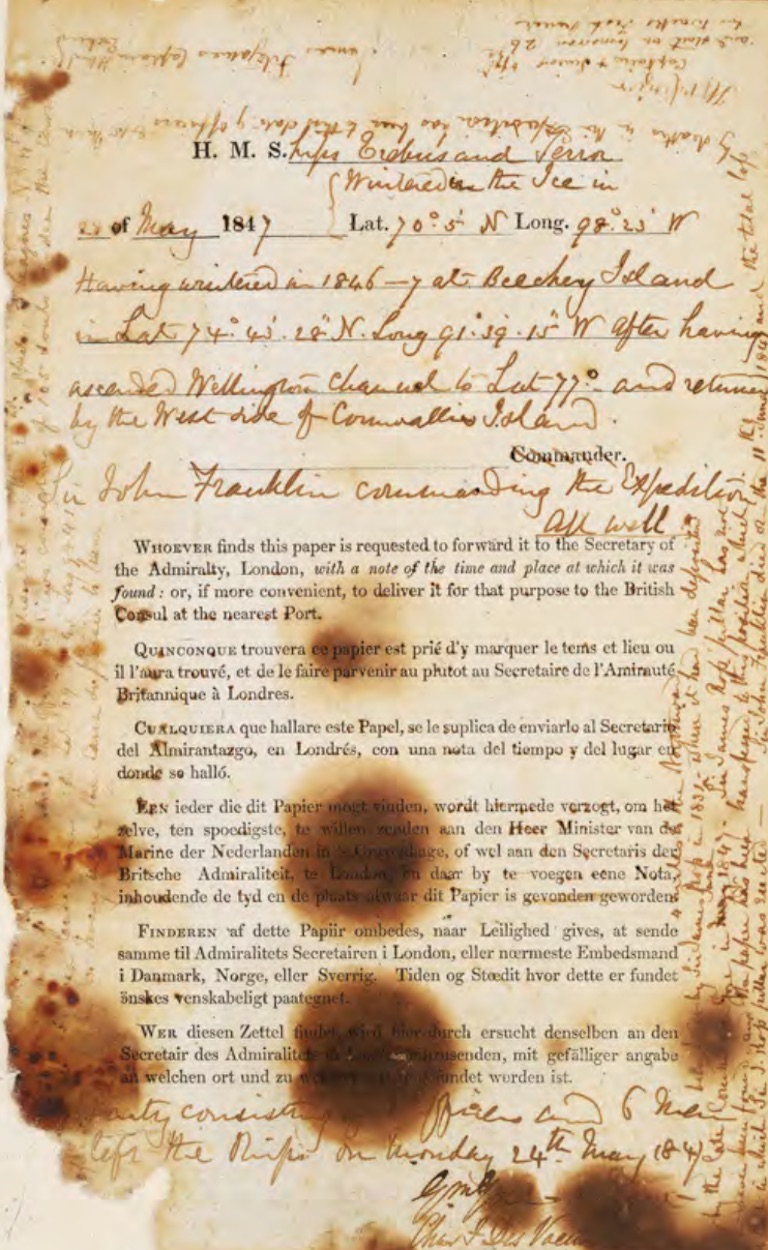

Rae’s findings radically narrowed the search area. And in 1859 a search expedition financed by Lady Franklin and led by naval officer Leopold McClintock turned up the “Victory Point note” — the only written document yet found from a member of the expedition illuminating its ultimate fate.

That note indicated that in 1848, with the ships trapped in ice and twenty-four men already dead, John Franklin among them, the remaining 105 men abandoned the ships and set out marching southward towards the Arctic coast.

McClintock also found dead bodies, an abandoned lifeboat, and numerous small artifacts, all of which raised more questions than they answered.

In the 1860s, following the discovery of the Victory Point note, the fluent-English-speaking woman Tookoolito, together with her husband, Ebierbing, enabled the American Charles Francis Hall to interview Inuit who had actually gone aboard one of the ships before it sank.

They provided invaluable eyewitness accounts that would later give rise to theories about what had happened to the expedition.

And, in the 1870s, an Inuk named Tulugaq, working with Ebierbing, guided the American Frederick Schwatka in searching for written records along the coasts of the continent and King William Island.

They found none but unearthed still more bodies, new locations, and eyewitness accounts. To these searchers, an aging Inuk named Puhtoorak said that in the early 1850s he had visited a big ship frozen in the ice and had seen the body of a dead white man lying in a bunk. He pointed to a location near where, more than a century later, the Erebus was eventually found.

Without these Inuit guides and translators, the truth of the Franklin expedition would never even have begun to emerge.

Through the twentieth century, scholars and researchers published works and debated theories, but Inuit testimony provided the breakthrough.

In 1991, after sifting through hundreds of pages of Inuit testimony gathered by Charles Francis Hall with the help of Tookoolito and Ebierbing, Canadian David C. Woodman published Unravelling the Franklin Mystery: Inuit Testimony, which offered a new, more complex reconstruction of the final months of the expedition.

Woodman argued that some of the 105 men who abandoned the two ships in 1848 later returned to one of them and remained aboard as it travelled south in the ice, with some men surviving as late as 1851.

He provided a rough geography for more focused ship searches. The late Inuit historian Louis Kamookak (1959–2018), who spent much of his adult life investigating the Franklin story, was one of those who then pointed the way to the 2014 discovery of Erebus. A second hunter from Gjoa Haven, Sammy Kogvik, led the way to the 2016 finding of Terror. The Indigenous contribution can hardly be overstated (see the sidebar at the end of this article).

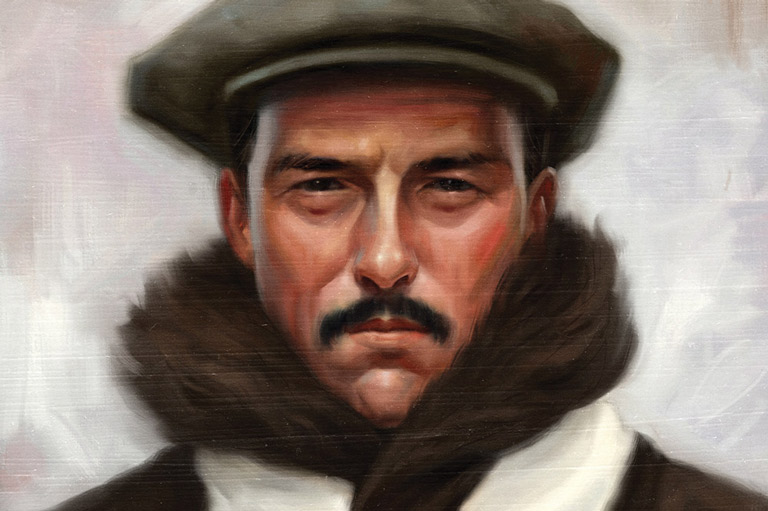

Nor would any commemoration of the lost Franklin expedition be complete without recognizing the role and the machinations of Jane, Lady Franklin. First, despite intense opposition, she got her husband appointed leader of the 1845 undertaking.

At age fifty-nine, over-weight, and out of shape, John Franklin was nobody’s first choice. Working behind the scenes, Lady Franklin secured the backing of several influential figures, foremost among them James Clark Ross, the clear front-runner who did not want the leadership.

Some argued that Franklin was not healthy enough to survive another Arctic winter, and his early death (June 1847) does raise questions.

After the two ships disappeared, Lady Franklin orchestrated an unprecedented search. Between 1848 and 1859, she variously organized, inspired, or financed eleven of the thirty-five search expeditions sent out by Great Britain and the United States — nearly one third.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

She wrote letters to international leaders, conducted subscription campaigns, consulted psychics, purchased sailing ships, and seconded officers from the Royal Navy. By stirring up public opinion and lobbying influential friends, she exerted relentless pressure on the British Admiralty and the Hudson’s Bay Company to keep searching.

After 1854, Jane Franklin fought tooth and nail to repudiate John Rae’s revelations that some members of the expedition had been driven to cannibalism.

She acquired the support of Charles Dickens, who shamed himself with a racist denunciation of the Inuit that has damaged his reputation forever.

Meanwhile, Lady Franklin repeatedly redefined the notion of geographical discovery to suit the lost expedition, ultimately advancing the nonsensical idea that halfway through the Northwest Passage, by reaching the Arctic coast of the continent, the starving sailors “forged the last link with their lives.”

Even today, educated people who should know better deny geography and abandon logic to follow her in arguing that the Franklin expedition somehow discovered the Northwest Passage.

Never mind. The search for the lost ships did accomplish the mapping of the Canadian Arctic. And Lady Franklin herself has earned a place in history as an early marketing genius. By erecting statues and memorials of her husband hither and yon, from Lincolnshire and Westminster Abbey in England to Hobart, Tasmania, she turned her hapless husband into an Arctic hero.

And so we arrive at final questions. From the note found at Victory Point on King William Island, we know that in April 1848 105 men departed the two ice-locked ships.

The note tells us that already nine officers and fifteen seamen had died. That represents thirty-seven per cent of officers but just fourteen per cent of crewmen, and the discrepancy is even greater if we subtract the three dead men buried on Beechey Island.

Why so many officers? Why such disproportion? Researchers have spent vast amounts of time and energy inquiring into the deaths of the first three sailors to die, even to the point of exhuming and analyzing their remains.

Did lead poisoning kill these men? Botulism? Zinc deficiency and tuberculosis? But here’s another question: What if those three early deaths were anomalies that contribute nothing to solving the larger mystery?

Perhaps those later twenty-one deaths resulted from some unrelated accident. A few scholars have wondered if those men ingested something the others did not. But none has connected the tragic fate of Franklin with the catastrophe that befell Dano-Norwegian explorer Jens Munk.

In 1619–20, while seeking the Northwest Passage, Munk led two ships filled with sailors in wintering at present-day Churchill, Manitoba. There his expedition lost a staggering sixty-two men out of sixty-five.

While researching my book Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage, I read Munk’s journal in translation and then turned up an article by Delbert Young that was published more than four decades ago in The Beaver magazine, now Canada’s History. In “Killer on the ‘Unicorn,’” Winter 1973, Young blamed the catastrophe on poorly cooked or raw polar-bear meat — a threat not then well understood.

Soon after reaching Churchill in September 1619, Munk reported that at every high tide white beluga whales entered the estuary of the river. His men caught one of them and dragged it ashore.

The next day, a “large white bear” turned up to feed on the whale. Munk shot and killed it. His men relished the bear meat. Munk had ordered the cook “just to boil it slightly, and then to keep it in vinegar for a night.” But he had the meat for his own table roasted and wrote that “it was of good taste and did not disagree with us.”

As Delbert Young observes, Churchill sits at the heart of polar bear country. After that first feasting the sailors probably consumed more polar bear meat. During his long career, Munk had seen men die of scurvy, and he knew how to treat that disease. He noted that it attacked some of his sailors, loosening their teeth and bruising their skin. But when men began to die in great numbers, he was baffled.

Their illness went far beyond anything he had seen. His chief cook died early in January, and from then on “violent sickness ... prevailed more and more.”

After a wide-ranging analysis, Young identified trichinosis as the probable killer — a parasitical disease that is endemic in polar bears.

Infected meat, undercooked, deposits embryonic larvae in a person’s stomach. These tiny parasites embed themselves in the intestines. They reproduce, enter the bloodstream, and, within weeks, encyst themselves in muscle tissue throughout the body.

They cause the terrible symptoms Munk describes and, left untreated, can culminate in death four to six weeks after ingestion.

So, back to the Franklin expedition. Could trichinosis, induced by eating raw polar bear meat, have killed those nine officers and twelve seamen? And could it have galvanized the remaining men into abandoning the ships?

Could it have rendered many of them so sick that they could hardly walk straight and have made the faces of some look black, so that they had to be quarantined in a separate tent? All of this accords with Inuit testimony.

In recent years, while visiting Beechey Island with Adventure Canada, I and my fellow voyagers have been driven off by polar bears. Rather than fire guns into the air, we retreat into the Zodiacs at the first sign of the bears’ approach. Faced with that same situation, Franklin’s men would have responded differently. They would have shot those bears and eaten them.

It’s true that, by the mid-nineteenth century, some sailors might have heard that polar bear meat could be dangerous. But can anyone doubt that the men of the Franklin expedition, subsisting on short rations and desperate for a change of diet, would have eaten it anyway?

Like Munk’s men, they would not have seen terrible and baffling symptoms arise until later.

In my view, undercooked polar bear meat, unevenly distributed among officers and crew, led not only to those lopsided fatality statistics but to the flight from the ships and, ultimately, the destruction of the expedition.

Within the next two or three years, those underwater archaeologists from Parks Canada will almost certainly turn up decisive evidence — written records, or human remains, or both — as they investigate the Erebus and the Terror. Do not be surprised if they determine that the sailors ate uncooked polar bear meat and fell victim to trichinosis.

How Indigenous Peoples Kept Franklin Alive

Without certain decisive interventions of Indigenous peoples we would not now be commemorating any expedition bearing the name of Sir John Franklin, because he would have been dead long before departure.

The first occasion occurred in 1821, when Yellowknives Dene led by Akaitcho saved Franklin from starving to death. On July 18 of that year, the thirty-five-year-old lieutenant established a campsite overlooking Coronation Gulf at the mouth of the Coppermine River in what’s now Nunavut.

A few kilometres upriver, he had taken unhappy leave of the Yellowknives, who had warned him against continuing his journey that late in the year.

Akaitcho had told Franklin that if he ventured east along the Arctic coast he would run out of food and would never return alive. Impervious to Indigenous advice, the Royal Navy man proceeded to the coast. From there, unprepared and short of food, he led nineteen men eastward.

As predicted, he encountered neither animals nor Inuit hunters; and, when Franklin finally did turn back, the expedition devolved into a death march marked by starvation, murder, and cannibalism. Eleven men died, and Franklin survived thanks only to a rescue party sent by Akaitcho.

Back in England, after publishing a narrative drawing heavily on the work of subordinates, Franklin was celebrated as “the man who ate his boots.” And by 1826 he was back in the Arctic again, charged with mapping more coastline. This time, the Indigenous intervener was an Inuit guide named Tattannoeuck who rescued the Royal Navy man from disaster and almost certain death.

On July 7, having reached the mouth of the Mackenzie River with two boats and fifteen men, Franklin felt moved to visit “a crowd of Esquimaux tents” on an island four kilometres distant. Halfway there, shallow waters forced a halt; but Franklin beckoned the Inuit to approach. Soon the boats were surrounded by two hundred and fifty Siglit Inuit in seventy-eight canoes.

Having invited two chiefs into his boat, Franklin found himself forcibly held in place while forty men produced knives and began ransacking the boats. Tattannoeuck jumped into the water, Franklin wrote later, “and rushing among the men on the shore, endeavored to stop their proceedings, till he was quite hoarse with speaking.” Franklin’s second-in-command, George Back, scared off most of the would-be thieves by firing into the air.

Tattannoeuck then “intrepidly went” ashore and told the Inuit that the white men had come only to help, and that he himself, well-clothed and comfortable, was proof “of the advantages to be derived from an intercourse with the whites.”

Tattannoeuck continued in this vein while surrounded by more than three dozen men, “and all of them with knives, and he quite unarmed. A greater instance of courage has not been I think recorded,” wrote Franklin.

Tattannoeuck remained onshore, talking and then singing with the strangers until at midnight the tide began to rise, and Franklin and his men set off rowing westward. If not for Tattannoeuck, these events at “Pillage Point” would certainly have ended differently.

Thanks to Akaitcho and Tattannoeuck, a Yellowknives Dene and an Inuk, John Franklin lived to see 1845. But then, by later vanishing into the Arctic, he engendered a search that engaged British, American, and even French adventurers, some of whom lost their own lives.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!