Sir John Franklin's Erebus and Terror Expedition

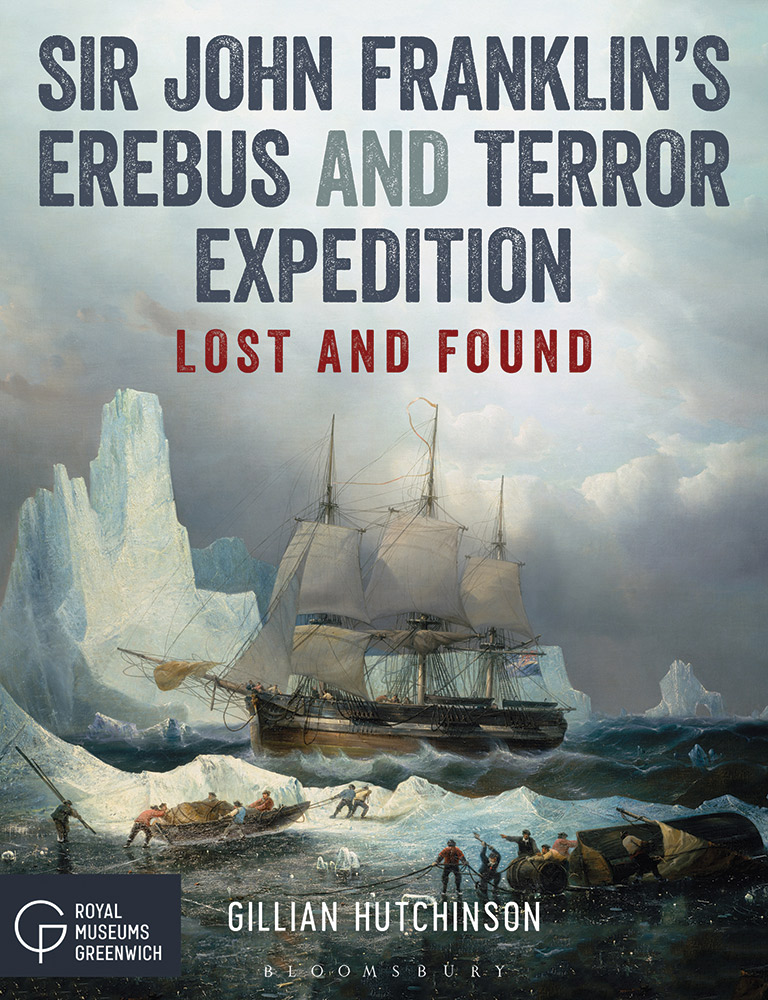

Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror Expedition: Lost and Found

by Gillian Hutchinson

Adlard Coles Nautical, 175 pages, $37

A double review with

Erebus: One Ship, Two Epic Voyages, and the Greatest Naval Mystery of All Time

by Michael Palin

Random House Canada, 368 pages, $37

Few episodes in Canadian history have inspired as many books and articles as the missing last expedition of Sir John Franklin. The recent discoveries of the wrecks of HMS Erebus in 2014 and HMS Terror in 2016 have further fuelled this publishing phenomenon. An overriding question for readers, whether Franklin enthusiasts, scholars, or members of the general reading public, is the extent to which any new book adds to the existing knowledge of Franklin, his ships, and the men who accompanied him to the Arctic.

Gillian Hutchinson’s Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror Expedition is an illustrated history focussing on images of Franklin artifacts, maps, written documents, paintings, and wood engravings, as well as the collection of daguerreotype portraits of the expedition’s officers made just before their departure in 1845. Many of the original objects reside in British collections, including at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, which co-published the book. Modern-day aspects of the Franklin story are covered in the penultimate chapter and illustrated with arresting surface and underwater colour photographs of the search and the wrecks discovered by Parks Canada’s researchers.

These diverse images carry much of the story that is told in mostly chronological fashion in ten chapters, from the search for the Northwest Passage to the modern-era investigations and discoveries of the ships. Exceptions to the chronological approach are chapters on Franklin and the two ships he commanded on his last fateful expedition.

Despite including several references to Inuit and reproducing the map of Franklin sites drawn by the Inuk Innookpoozhejook for the American explorer Charles Francis Hall, this book is light on Inuit aspects of the story. A chapter entitled “McClintock discovers the fate of the Franklin Expedition” does not fully acknowledge the contribution of Inuit who collected and traded many of the artifacts brought back by the explorers, and who contributed knowledge that significantly enabled McClintock’s revelations of 1859.

A welcome feature is the book’s transcription and publication of the original muster tables of the two ships, heretofore only accessible to researchers at the British National Archives. Providing the names, ages, places of birth, and family data of every crew member, the muster tables are valuable documents for Franklin researchers. Hutchinson’s book’s most important contribution is its selection and display of a large number of original artifacts relating to Franklin’s expedition, predecessor forays by the British navy, and succeeding voyages in search of the missing party.

As suggested by its title, Michael Palin’s Erebus: One Ship, Two Epic Voyages, and the Greatest Naval Mystery of All Time treats the larger history of HMS Erebus throughout its long history with the British navy, including its voyage to Antarctic regions from 1840 to 1843, its fateful last expedition of 1845, and the mystery regarding its fate. Palin is a gifted storyteller and has an unerring eye for illuminating anecdotes. His gripping account of the voyage of Erebus to Antarctica is particularly good and details an important period that will not be as familiar for many Franklin students. Palin’s treatment of work and daily life aboard the ships is engrossing. Drawing on personal correspondence, he offers insightful interpretations of the personalities of Franklin’s senior officers.

Palin provides a bibliography of books and articles he relied upon in researching his book and offers useful accounts of some of the important manuscript sources in the text. Yet, while he clearly made extensive use of original materials in British archival collections, it is disappointing that he did not incorporate these sources into his bibliography or reference them in notes. Hutchinson similarly does not provide notes, and neither author appears to have consulted North American manuscript collections. Palin compensates in part by relying on David Woodman’s treatment of Inuit sources in the latter’s book Unravelling the Franklin Mystery. Palin’s careful analysis of British manuscript sources is impressive, but he has not investigated Hall’s voluminous original field notebooks and journals at the Smithsonian Archives in Washington, D.C., the most important source of Inuit knowledge on the Franklin expedition from the nineteenth century.

British sources cannot in themselves tell the full story of the Franklin expedition. For example, Palin draws on comparative evidence to reconstruct expedition life on Erebus and Terror during nearly two years of besetment in the ice until the ships’ desertion in April 1848, implying that they largely confined their activities to life aboard ship. However, we have direct evidence in Inuit accounts collected by Hall that suggests Franklin’s men made a series of forays to King William Island in this interval, travelling well down its western shores. Palin summarizes the limitations of the provisions brought by the party from England but does not reference Inuit evidence of hunting and fishing activities by Francis Crozier’s party in areas between Cape Crozier and Cape Herschel. As well, Palin states that Franklin’s men did not seek to trade with Inuit for food, but Hall’s oral histories reveal that Crozier did trade with them for seal meat on at least one occasion.

Both books are engagingly written and accessible to a wide audience. They comprise significant assemblages of current knowledge of Franklin’s last expedition as revealed in the documentary sources and artifacts in British archives and museums and are thereby worthwhile contributions to the literature. What remains to be detailed and studied more fully is the evidence of Inuit observers as recorded from the 1850s to the present — something that holds the potential to further revise or even overturn existing understandings of this famous expedition and its many mysteries.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement