The Great Canadian Reindeer Project

On February 15, 1935, Andrew Bahr prepared to lead a bedraggled, scruffy herd of nearly 2,500 reindeer across the frozen, windswept channels of the Mackenzie River Delta. Departing from Alaska, he had been on the trail nearly five years. It was a venture that was supposed to have taken eighteen months, and this was the final push.

“Reindeer Near End of Four-Year Trek” announced the New York Times on October 7, 1934, “Canada Grooms Alaskan Herd for 70-Mile Lap Over Delta Ice to Mackenzie Basin.”

The previous fall had been cheerless, monotonous, and fraught with anxiety for Bahr and his small band of weary herders. As February approached, impatience and fear were at a peak. Bahr anxiously awaited the perfect conditions necessary for the final drive.

An attempt the previous spring to cross the delta had met with failure when an unexpected storm scattered the herd. It demoralized the herders and nearly ended the seemingly doomed venture. Bahr feared that the herd might never be brought across the delta. If the Mackenzie crossing failed for the second time, it could mean the end of the drive, the loss of four-and-a-half years of labour, the forfeiture of a small fortune for the Lomen Brothers Reindeer Corporation of Alaska, and the disappearance of a hopeful Canadian government enterprise, years in the planning.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The saga began just before the great market crash of 1929, when an Alaskan entrepreneur named Carl Lomen — the “Reindeer King” — signed a contract with the Canadian government to ship a herd of 3,000 reindeer 2,400 kilometres from Naboktoolik, Alaska, to the Mackenzie Delta, Northwest Territories, ostensibly to feed starving Inuvialuit (the Inuit people of the western Arctic).

As part of the Canadian government’s plan for asserting its sovereignty over the Arctic, it was establishing Royal Canadian Mounted Police outposts throughout the region and encouraging the Inuit to settle at permanent trading and administrative posts. In the 1920s, the western Arctic caribou herd did not yield sufficient numbers to feed the expanding communities of Aklavik and Tuktoyaktuk.

While hunting for a living had become unreliable, animal husbandry was believed to be stable and predictable. Reindeer held the most promise for success for domestication because of their suitability to the northern climate and their astounding breeding potential — a properly managed herd could double in size every three years.

“The Canadian government saw this as a single solution to two of their problems,” writes Thomas Conaty in his 2003 book titled The Reindeer Herders of the Mackenzie Delta. “First, reindeer herds would provide a constant supply of hides and meat for Inuit. Second, herding could be a means of settling Inuit in at least semi-permanent localities.”

Reindeer, a more easily domesticated cousin of the wild caribou, that the New York Times called “the camel of the frozen north,” had been thriving in Alaska for several decades since two separate herds were brought over from Siberia and Lapland near the end of the nineteenth century.

Advertisement

By 1925, the various herds in Alaska numbered more than 350,000 animals. Between 1918 and 1925, nearly two-million pounds of reindeer meat was processed and shipped south to the U.S. mainland. “The flavor of reindeer meat offers not the slightest suggestion of gaminess or wild animal flavor,” stated Alfred W. McCann, an American gourmand and newspaper columnist in New York in 1925.

“The meat is finer in texture than beef and far more tender. It has all the juiciness of beef with the texture of lamb, but tastes like neither. It is actually delicate in flavor.” McCann was promoting reindeer meat as a quality alternative to beef. Annual shipments had grown to 700,000 pounds by 1925, making it one of the most important industries in Alaska, second only to fishing. The reindeer industry was a local success story with local Alaskan ownership that employed over 600 Inuit and several hundred Laplanders.

The Canadian government, seeing the success of the reindeer industry in Alaska, contacted the Lomen Brothers Reindeer Company with an unprecedented proposal to establish a Canadian herd. They settled on a price of $75 a head for the delivery of 3,000 animals to Reindeer Station on the east side of the Mackenzie River Delta totaling $225,000 — a small fortune in those days.

The drive was optimistically expected to be completed by 1931, in less than two years. “If success can be achieved after the reindeer have been introduced,” claimed an editorial in the Montreal Gazette when news of the deal became public, “a new era may be opened up for Canada’s northland. A meat industry of great proportions may be developed.” It was to be called the Canadian Reindeer Project.

Neither the Canadian government nor the Lomens had any real concept of the logistical difficulties of manoeuvering thousands of fickle animals 2,400 kilometres across the northern tundra, but they knew just the man for the job. Andrew Bahr, a veteran Lap herder who had come to Alaska during the Klondike gold rush in 1898, was respected as one of the most dependable herders in Alaska.

Bahr’s prophetic words of wisdom, gleaned from years of experience, should have been a warning to the overly optimistic planners. “The deer run the herder,” he claimed, not the other way around.

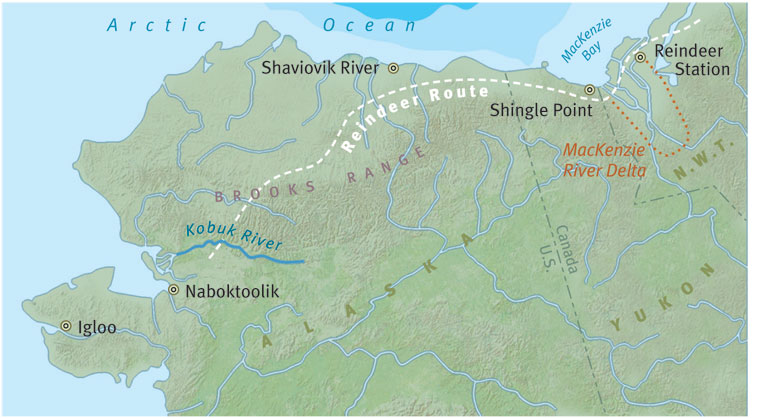

Bahr’s planned route cut across Alaska to Howard Pass in the Brooks Range and then followed the coast of the Arctic Ocean east into Canada. He ruled out a more southern route because it was impossible to drive reindeer through trees, and he avoided a northern route along the Alaska Coast to avoid mixing his animals with the small, local Inuit herds.

In 1926, the Canadian government had hired Danish botanist Alf Erling Porsild to scout the western Arctic for a suitable region to be the nucleus of the Canadian reindeer industry. In 1928, he reported that the Mackenzie River Delta held the greatest potential for success. Porsild eventually settled on a suitable range, and the government constructed a small town called Reindeer Station to be the administrative centre.

The drive had an inauspicious beginning. Near the end of November 1929, just as the herd was assembled from the surrounding region, a vicious storm lashed the tundra and destroyed the corral, and the reindeer issued forth to wander across the landscape. Unrelated events cast a shadow over the drive as well: on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929, the world stock markets crashed, sending thousands out of work, driving the price of beef, and eventually reindeer, to all-time lows.

The deal had already been signed, however, and in December 1929, a kilometre-long, undulating mass of reindeer numbering 3,442 were soon on the trail, milling, snorting, sniffing, and seemingly overbalanced by their massive antlers under the stark polar sky. They moved under the watchful eye of the sometimes taciturn, yet indomitable, Andrew Bahr. They were on their way to Canada.

Bahr, his men, and the large herd of reindeer would spend the next five years on the trail toiling through some of the most rugged terrain on the continent. They would endure wildly fluctuating temperatures, from sweltering humidity to bone-chilling polar gales; they would struggle through snow up to their waist and wade through stagnant swamps; they would suffer from lack of food, inadequate clothing and supplies; and, perhaps worst of all, they would be paid rather poorly.

Nevertheless, they plodded on each winter as blizzards lashed them piteously and wolves circled the herd driving the reindeer into a frenzy. “We were always looking for wolves,” recalled Matthias Hatta, one of the Lap herders. “They would come around in the dark and when it was stormy. You couldn’t see them. You would just fire into the air and scare them away ... they were mostly white wolves, like the snow ... there were sometimes twenty in one bunch.”

Reindeer are notoriously difficult to herd because they prefer walking into the wind. In the Arctic, shifting winds caused the animals to bolt, and Bahr spent weeks trudging back and forth across the tundra to retrieve them. Other problems hindered the drive as well.

When temperatures rose unexpectedly, the snow melted into a slushy quagmire, bogging the sleds down in the mess. When the temperature froze again, the land became smothered under a blanket of ice that prevented the reindeer from feeding on the lichens hidden underneath.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Bahr was philosophical. “We are now just training,” he reputedly said to his herders after the first year, “training dogs and training men. I must do much talking now to tell and show how things must be done. By and by, everyone will know what to do.”

They spent the first spring camped along the banks of the Kobuk River for the fawning season. The fawns were born in late April and early May and matured over the summer before the chaotic herd set off for the jagged spires of the Brooks Range in mid-October 1930. The Lomens had placed food caches along the route through Howard Pass, but for the herders it was a dreadful nightmare as frigid winds froze their faces, snow clogged the rocky chute, and the reindeer became frightened and edgy.

At -50° Celsius, a mist formed about the animals, enveloping the herd in an eerie, steaming cloud that blocked all vision and communication. Travel was excruciatingly slow, averaging less than two kilometres a day.

“We would have to be out watching the herd, walking around them, night and day looking for wolves and chasing some of the deer that would stray and get lost,” noted Matthias Hatta. “It was sixty below — sometimes seventy — and cold winds. We would work in shifts of twenty-four hours, but sometimes we would have to keep working for forty-eight hours or more. We didn’t get much sleep anytime.”

Once through the mountains, Bahr and his men spent the next two tedious years slogging back and forth along the same stretch of coast from the Shaviovik River to the Mackenzie Delta. The animals stampeded twice, in July 1931 and March 1933, and the bulk of the winter travel season was spent trying to locate the wayward beasts. (The arrival of the herd to their winter grazing ground was noted in the June 1933 issue of The Beaver.)

While winter travel had its difficulties, the idle summers near the coast were even worse. Added to the extreme boredom of continuously wandering the perimeter of the grazing herd, the insects almost drove the herders mad. Pestering black flies and mosquitoes hovered about them in a buzzing cloud. They wiggled through crude face netting and swarmed about the frying pans, crisping into a crust on the food.

For the reindeer, it was horrible. Some animals nearly died from blood loss, while others fell prey to the dreaded warble fly, which laid its eggs in their skin. The larvae painfully burrowed through the flesh until escaping the following spring. Another pest was the nostril fly, which laid its eggs in reindeer noses. The larvae gestated until the following summer when they burrowed into the throat and the poor reindeer sneezed them out in a bloody mass.

After three years on the trail, only two thousand reindeer were still with the herd. Hundreds had frozen to death, hundreds more bolted and were never recovered, and countless others were weakened by insects and devoured by wolves.

After three years on the trail, only two thousand reindeer were still with the herd. Hundreds had frozen to death, hundreds more bolted and were never recovered, and countless others were weakened by insects and devoured by wolves. The drive was years behind schedule, and all Bahr, who by now had earned the nickname “The Arctic Moses,” could tell the Lomens and the Canadian officials was that he was “making haste slowly.”

Crossing the Mackenzie Delta was the final obstacle, but a third stampede in June 1934 almost broke Bahrs spirit. After leading the herd onto the ice, a storm blew in. Through severe wind and cruel temperatures, the herders could not stop the frightened animals from bolting back to land.

To see the remnants of the herd fleeing west again was a devastating blow. The herders had had almost all they could take of the solitary tedium, poor food, and punishing conditions (one version of this account was published in the June 1934 issue of The Beaver). After wearily retracing his path and rounding up his flock, Bahr stationed the remnants of the herd at a good feeding ground near Shingle Point on the Arctic Coast for the long wait for winter. This one random storm delayed the arrival of the herd by nearly one year.

Finally, on February 15, 1935, more than five years after they set out, Bahr judged the conditions good for a crossing of the frozen Mackenzie River and led his weary band out onto the expanse of ice for the second time. No unseasonable storms shattered the herd, the snow cover held, and Bahr was able to lead them from island to island to the east side of the river after a three-day journey. The herd was corralled at last, at Reindeer Station, on March 6, 1935. It was the end of an odyssey. Although 2,370 reindeer reached their destination, more than three-quarters of them were born along the route.

In 1937, the United States government assumed control over the reindeer industry in Alaska and made it illegal for anyone other than an Indigenous person to own a female reindeer. The industry, already weakened by the Depression, collapsed within a few years, reduced from producing over 700,000 pounds of reindeer meat annually to only a few thousand. The industry has only been on the rebound in recent decades. The Canadian reindeer industry has had a similarly up-and-down history.

Advertisement

The objective of the Canadian government was for native peoples to become the independent owners of the herds, but initially, several families of Laplanders were hired to manage the project and teach the necessary skills in reindeer husbandry.

The technique of herding practiced by the Laplanders was called “close” herding. A family group travelled with the herd at all times, keeping a close watch on them. In the Canadian Arctic, however, this proved difficult.

The Canadian herd was huge by traditional standards — perhaps ten times the size of an average herd in Lapland — and tended to consume the forage quickly. Slow herding was also inefficient in time and labour and produced little remuneration.

In the 1940s, Canada’s great reindeer herd was split into four independent herds, which struggled along into the 1960s. During this time, Mikkel Pulk, head of the only Lapland family remaining, was the chief herder. Then the herds were again amalgamated and the style shifted to “open” herding, whereby the animals were turned loose in a specific range with little daily observation or direction. The grandson of Mikkel Pulk, Lloyd Binder, is part owner and manager of the herd today.

Initiated by the Canadian government and run by immigrant Lapland herders, the Canadian Reindeer Project was a monumental achievement with a noble objective. In 1929, the Edmonton Journal called it “the most spectacular reindeer drive in the history of the industry,” and it has remained so to this day.

Although it has admittedly never lived up to its original optimistic billing, reindeer herding has evolved into a multi-million-dollar industry in Canadas’ North. But practical considerations aside, the Canadian Reindeer Project stands as one of the most audacious, unusual, and exotic tales in Canadian history.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!