Perfect People, Perfect Country

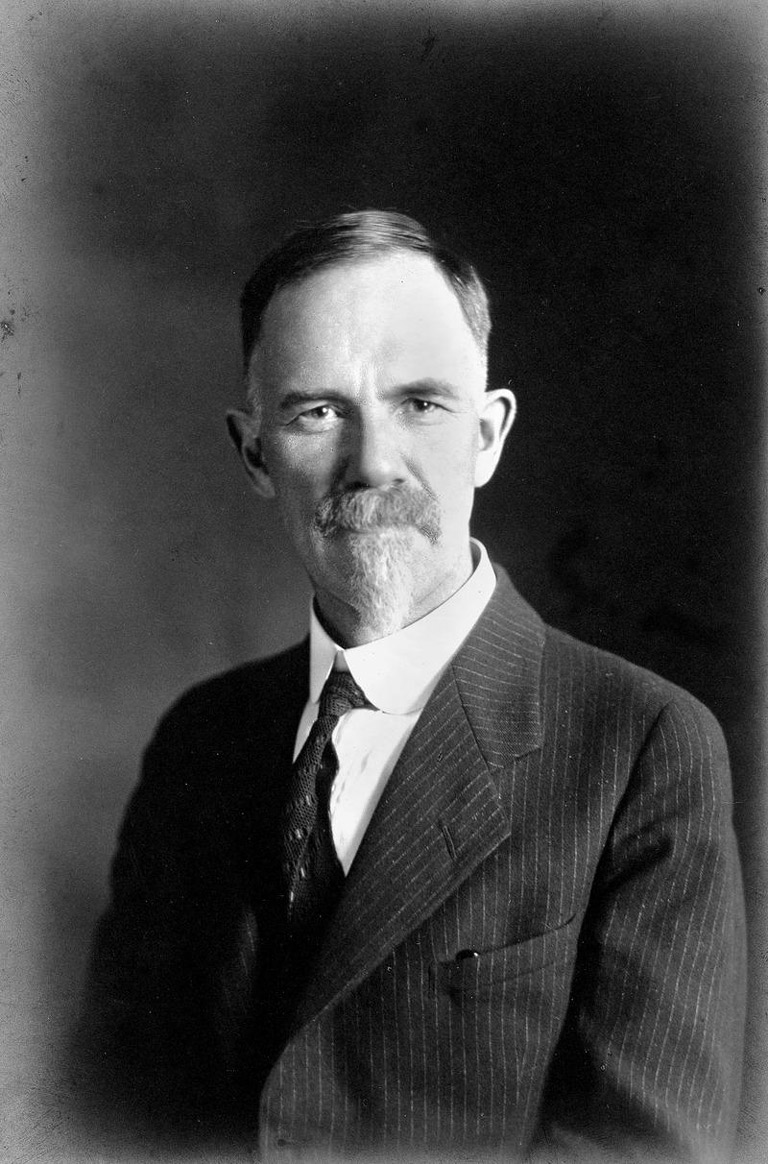

Dr. Helen MacMurchy had a noble mission. She was determined to save Canada from the ills of the modern world. To accomplish this, however, meant confronting the problem of the “feeble-minded,” as she and others called “mentally defective” individuals who threatened the health of the nation.

MacMurchy is remembered today as one of the country’s pioneers of public health.

Although she often sounded like such champions of the early twentieth-century eugenics movement as American Charles Davenport in her passionate conviction that feeble-mindedness — clearly linked, she argued, to crime, prostitution, and juvenile delinquency — and an open-door immigration policy posed a real threat to Canadian survival.

Indeed, these fears were realized when W.G. Smith, a psychology professor at the University of Toronto, published his book A Study in Canadian Immigration in 1920.

Among other “disturbing” facts, Smith’s calculations showed that while at New York’s Ellis Island, “the Americans’ rate of rejection of mental defectives was one to every 1,590 immigrants ... Canada’s was only one to every 10,127 as evidence of leniency of the latter country’s screening process.”

MacMurchy was influenced by the work of such U.S. eugenicists as Henry Goddard and, in particular, Richard Dugdale.

Dugdale was the author of a celebrated heredity study published in 1877 that showed how the union of an upstate New York frontiersman he called Max Juke and his “degenerate” (or morally inferior) wife in the 1730s were responsible for seven generations of misfits and criminals.

Like her mentors, MacMurchy accepted that “individual inadequacy,” rather than environment factors, had caused a crisis and required a bold solution.

“Poverty, of course, is not a simple, but a complex condition,” she wrote in a 1912 report. “It probably means poor health, inefficiency, lack of energy, less than average intelligence or force in some way, not enough imagination to see the importance of details.”

Born in Ontario in 1862, MacMurchy, seemingly prim and proper from a young age, was also unorthodox; she opted to become a doctor, which was not a usual career choice for a Canadian woman at the turn of the century.

She graduated from Women’s Medical College in Toronto in 1901 and then furthered her studies at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Returning to Canada, she was the first woman offered a position in the Toronto General Hospital's Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

She gradually became more active in public health and starting in 1906 submitted reports on the feeble-minded to the Ontario government. She was appointed the province’s first inspector of the feebleminded in 1914 and briefly worked for the Ontario education department supervising special-education classes.

Recognized for her expertise in the area, the federal government recruited her for its newly established Department of Health in 1920. She ran its Division of Maternal and Child Welfare for the next fourteen years, taking a special interest in reducing infant mortality — a problem she typically blamed on “ignorant mothers.”

The same year she became an Ottawa civil servant, she also published her bestselling book The Almosts: A Study of the Feeble-Minded (1920). Using research she had conducted during her work as Ontario’s inspector of the feebleminded, MacMurchy educated Canadians (as well as Americans, since the book was published in Boston) beyond the medical and political communities on the unfit and degenerate menace afflicting the country — yet always with a feeling of empathy.

One had to treat the feeble-minded with care, she noted, yet never lose sight of the fact that they were abnormal and had to be treated as such. “It is the age of true democracy,” she wrote, “that will not only give every one justice, but will redeem the waste products of humanity and give the mental defective all the chance he needs to develop his gifts and all the protection he needs to keep away from evils and temptations that he never will be grown-up enough to resist, and that society cannot afford to let him fall a victim to.”

Should society, in fact, have failed these hopeless and helpless people, then the consequences would be severe. The feeble-minded might have been a small percentage of the total population, but as she maintained in a 1916 report — “with dubious statistical precision,” as Canadian eugenics historian Angus McLaren has put it — they accounted for the vast majority of alcoholics, juvenile delinquents, unmarried mothers, and prostitutes.

Quoting from the work of an American physician, Dr. Walter Fernald, she expressed the sentiment shared by eugenicists across North America that “every mental defective is a potential criminal.”

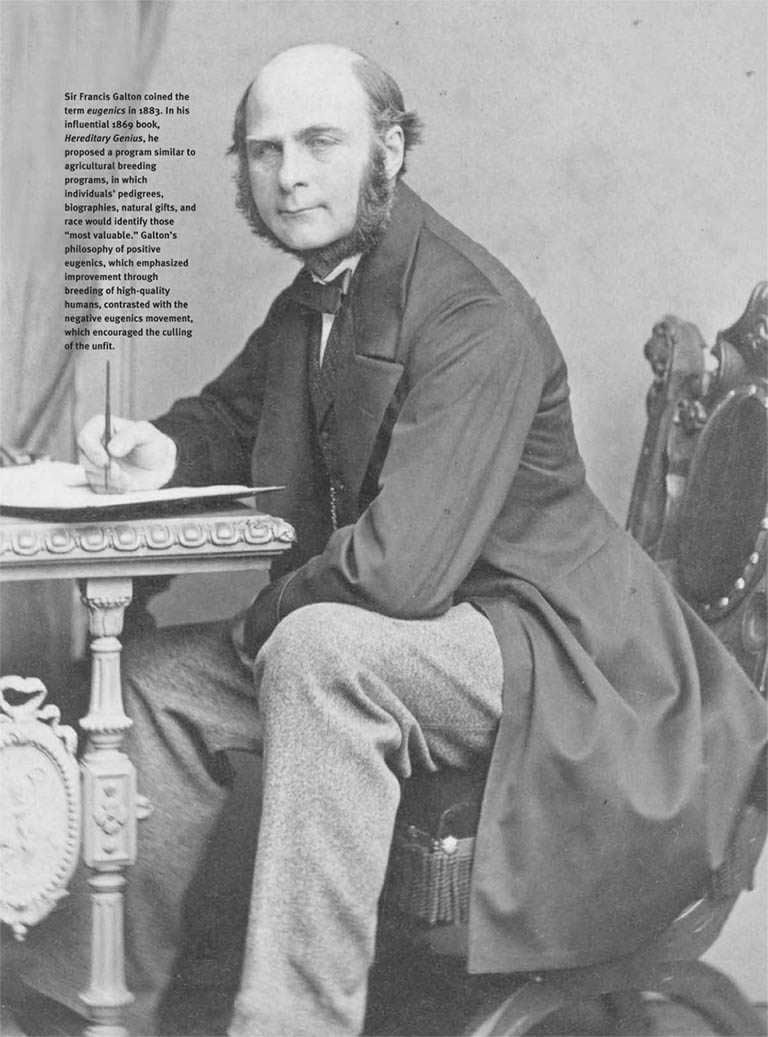

It was Charles Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton who coined the term eugenics in 1883, following the publication of his book Hereditary Genius in 1869. It was derived from the Greek root meaning “good in birth” or “noble in heredity” to describe his utopian scheme.

Eugenics was, he said, “a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognizance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had.”

So convinced was he of the flawlessness of his theory, he believed “its principles ought to become one of the dominant motives in a civilized nation, much as if they were one of its religious tenets.”

The scientific and intellectual communities did not immediately embrace Galton’s plan for a better and fitter world. Many later did. Their faith in the paramount significance of heredity was not really confirmed until the turn of the century. In 1900, scientists showed renewed interest in and acceptance of the work of an Austrian monk and botanist named Gregor Mendel, who had extensively studied the breeding of pea plants in the 1860s.

From his experiments, Mendel had been able to draw reasonable conclusions about what he called “elements” — dominant and recessive genes — which were passed on from one generation to the next.

“Mendel’s law of segregation and independent assortment,” as it became known, laid the foundation of modern genetics (a term first used in 1906). It only made sense to early eugenicists that human traits — not just physical, but also intellectual and moral characteristics — were transmitted in the same way.

That was the view, at any rate, of influential scientists and writers like Karl Pearson in England and especially Charles Davenport in the United States, who operated a huge eugenics institution at Cold Spring Harbor, outside of New York City. Davenport participated in international eugenic conferences in Germany (organized by the International Society for Racial Hygiene) and was involved in national conferences on “race betterment” on how to improve “American stock.”

One such gathering took place in 1915 in San Francisco in conjunction with the Panama Pacific Exposition being held in the city at the time. Davenport’s group mounted an effective eugenics exhibit at the Palace of Education, complete with graphs, photographs, and portraits displaying the impact of heredity on the American population. For the thousands of people visiting the exhibit, it was a lesson in “the rapid increase of race degeneracy.”

During this period, and again in the early 1920s, middle-class Americans and Canadians could not hear or read enough about eugenics. Countless articles appeared in the New York Times and other newspapers espousing its virtues, and the best magazines — Harper’s Weekly, Atlantic Monthly, Saturday Evening Post, and the New Republic — profiled the movement’s proponents and analyzed their apparently scientifically sound findings.

Writers such as J.F. Bobbitt, Granville Stanley Hall (a prolific American educator), and particularly journalist Albert E. Wiggam, author of the 1923 bestseller The New Decalogue of Science, spread the gospel of eugenics across North America.

At Harvard, Columbia, Cornell, and other North American colleges and universities, eugenics found its way into the science curriculum. “We know enough about agriculture so that the agricultural production of the country could be doubled if the knowledge were applied,” claimed Charles Van Hise, a geologist and president of the University of Wisconsin.

“We know enough about disease so that if the knowledge were utilized, infectious and contagious diseases would be substantially destroyed in the United States within a score of years; we know enough about eugenics so that if the knowledge were applied, the defective classes would disappear within a generation.”

The tremendous appeal of the eugenics movement was partly based on hope and partly on fear — hope for building a stronger and more intelligent populace, and fear that the trend was going in the opposite direction.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Progressive-minded Americans and Canadians watched in trepidation as their respective countries were swamped by foreigners, who not only challenged the supremacy of the Nordic or Anglo-Saxon race, but also brought to their cities nothing but poverty, slums, crime, prostitution, and corruption.

“National deterioration,” was what pro-eugenic academics and propagandists called it in Britain.

Then the First World War began, and they saw their best and brightest march off to die in the battlefields of Belgium and France, while the unfit, weaklings, degenerates, and feeble-minded remained at home to reproduce more of their own kind. (It was not lost on eugenic supporters that improvements in modern medicine and the quality of life generally also permitted the weak and feeble-minded to survive and have children when in an earlier era they might have perished).

Most eugenicists dwelled incessantly on controlling the birth rate of the unfit, but for some, eliminating the feeble-minded altogether was the obvious next step.

In London, George Bernard Shaw, the Fabian socialist and dramatist, who preached positive eugenics, which emphasized the importance of “good breeding quality,” also argued that “extermination must be put on a scientific basis if it is ever to be carried out humanely.” Adding, “If we desire a certain type of civilization and culture, we must exterminate the sort of people who do not fit it.”

Novelist D.H. Lawrence was more direct and eerily prophetic. In a letter to a friend in 1908 he explained his plan to save the world:

“If I had my way, I would build a lethal chamber as big as the Crystal Palace, with a military band playing softly, and a Cinematograph working brightly; then I’d go out in the back streets and main streets and bring them in, all the sick, the halt, and the maimed; I would lead them gently, and they would smile me a weary thanks.”

Lawrence died in the south of France in 1930, not knowing that the Nazis would indeed implement such a devastating policy ten years later.

Most Canadian supporters of eugenics would not have gone that far. Education and a more efficient immigration inspection system were necessary.

But Helen MacMurchy, among others, also campaigned for segregation and sterilization of the “feeble-minded” as the best method to protect the country’s well-being. Birth control, in MacMurchy’s opinion, was not a practical solution — she referred to it as “unnatural” and “contrary to one’s higher instincts.”

Still, Canadian politicians were more reticent than were the Americans to introduce sterilization legislation. Following the precedent set in Indiana in 1907 — the first of more than a dozen states to pass sterilization laws — Dr. John Godfrey attempted five years later to introduce a sterilization bill for asylum patients in the Ontario Legislature.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Despite support from such esteemed medical experts as psychiatrist Charles Clarke of the Toronto General Hospital and a staunch proponent of eugenics, the provincial government took a more cautious approach.

Unlike Americans, some Canadians, perhaps, were not as certain that an aggressive eugenics program would result in a glorious future. Sensing that the public was uncertain how to proceed, Ontario politicians let the matter drop for the moment.

Throughout the twenties, women’s groups in particular continued to push for legalized sterilization. In British Columbia and Alberta, Nellie McClung, Judge Emily Murphy, and Henrietta Edwards, among others, believed sterilization was a panacea for society’s ills.

In her memoirs published in 1945, McClung recalled visiting one prairie family who had sterilized their feeble-minded daughter, named Katie. The effect was apparently soothing, almost magical.

“Katie was well and neatly dressed,” wrote McClung. “Her mother told me that she was taking full charge of the chickens now, and in the evenings was doing Norwegian knitting which had a ready sale in the neighbourhood. The home was happy again.”

Always more pragmatic than McClung, Emily Murphy, an Alberta police magistrate (considered the first female judge in Canada as well as the British Empire), was also more direct.

“We protect the public against diseased and distempered cattle,” she declared. “We should similarly protect them against the offal of humanity.”

Sterilization bills were introduced into the B.C. and Alberta legislatures. In B.C., the government decided to appoint a Royal Commission on Mental Hygiene in 1925. It took more than two years to study the issue, although the commissioners — who were influenced by developments in the United States — recommended the sterilization of individuals in mental institutions.

The editors of the Vancouver Sun added their support in an editorial. Sterilization, they wrote, was “the only reasonable way of protecting the strains from which the world must draw its leaders.” By the time the commissioners submitted their final report in 1928, however, there had been a change in government in B.C. and the matter was not resolved for another five years.

Events were more decisive in Alberta.

Support for a sterilization law had been voiced in the provincial legislature since the early 1920s. Lectures, presentations, and articles had convinced many Albertans of the pressing need to deal decisively with this issue. Asked Margaret Gunn, the president of the United Farm Women of Alberta in 1924:

“Shall we continue our present system of merely taking charge of the very lowest physical and mental types, those who cause a menace to the state, the feeble-minded who in large measure fill our jails and penitentiaries and make up the great substratum of humanity — social derelicts, doomed because of congenital inferiority to lead lives that are crass and unlovely, and to lower the vitality of our civilization?”

She advised the government to adopt a policy of “racial betterment through the weeding out of undesirable strains,” adding that “democracy was never intended for degenerates.”

George Hoadley, the health minister in John Brownlee’s United Farmers of Alberta government, concurred with such sentiments. Arguing that the continuing increase in the province’s feeble-minded population — a majority of whom he pointed out were foreigners — was an undue burden on taxpayers, he introduced a sexual sterilization bill in February 1928.

Still, not everyone approved. Soon Alberta newspapers were filled with letters to the editor from concerned citizens who questioned what they regarded as the government’s heavy-handed actions.

“Are we animals and soon to be classed as Tomworths, Holsteins or Clydes?” asked one writer in the Edmonton Journal.

“Possibly Mr. Hoadley in his desire for physical perfection will bring in a bill next year that all children, such as those suffering from infantile paralysis or any deformity, be taken to the high level bridge and thrown into the Saskatchewan.”

A group of prominent Edmonton residents organized the People’s Protective League to fight the proposed legislation, which it declared was “interfering with the rights of people.”

It was to no avail. The government passed Canada’s first sterilization act in early March along with provision for the establishment of a “eugenics board” (consisting of two medical practitioners and two lay people) whose job it was to evaluate each case on its own merits.

According to the act, parents or guardians were to be consulted before any medical procedure was to occur, a stipulation that was eliminated by the Social Credit government of William Aberhart in 1937. Alberta’s sterilization act remained untouched until it was finally repealed in 1972.

By then, 2,822 Albertans had been sterilized for reasons varying from possessing a “low IQ to apparent promiscuity.” (As Alberta historian Alvin Finkel also notes, in later years “some boys with Down’s syndrome had one testicle removed for the benefit of a researcher into the causes of Down’s.)

British Columbia instituted a similar bill in 1933, yet other provinces, including Ontario, where there always had been substantial support for such a law, felt that it was too drastic a measure. The Eugenics Society of Canada, organized by a group of committed academics and doctors in late 1930 to promote “race betterment” and sterilization, never stopped hoping that the situation would change.

During the thirties, Canadian and American physicians and scientists watched almost with envy as Hitler and the Nazis imposed their own eugenics program. In their view, it was something to behold.

According to a January 1936 article in the magazine Canadian Doctor, the Nazis’ policy had ensured that 200,000 unfit German citizens would not have children. The financial saving to Hitler’s government was supposedly enormous. That same year, Charles Davenport’s protégé Harry Laughlin was awarded an honorary doctorate of medicine by the University of Heidelberg for his eugenics work at Cold Spring Harbor.

He was unable to attend the ceremony but wrote to thank the university’s officials. It was, he noted, “evidence of a common understanding of German and American scientists of the nature of eugenics.”

Historians estimate that by the end of the Second World War, the Nazis, who had transformed their forced sterilization program of more than 400,000 individuals into a massive killing machine, had likely murdered 140,000 physically handicapped and mentally ill people.

At one mental institution in Nazi Germany, the staff toasted with beer the cremation of the ten-thousandth patient — a child gassed to death. In 1946, at the trial of Nazi doctors held at Nuremberg, one physician after the other stated that they had modelled their system after the one in the United States.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement