Leftover Questions

Kensington, P.E.I. April, 2022

“Hey Dad?” Ali wasn’t too sure about what she was seeing. It didn’t seem like it had been that long since they’d bought the fresh vegetables in the fridge drawer. Except now they weren’t looking too fresh. The carrots were getting wrinkly and the turnips had freckles.

She held up a bunch of celery. “Should I just chuck this stuff?”

Her dad looked up from the sink where he was scrubbing mushrooms. To make her point, Ali bent a stalk of celery. No snap. It just curved.

“Put it in the compost,” her dad said. “But don’t let Grandma see you.”

A cheerful voice floated down the hall. “Don’t let Grandma see what?”

Ali shrugged and grinned at her dad as her grandmother walked into the kitchen, scanning for whatever it was she wasn’t supposed to see. Ali’s dad popped the lid onto the compost bucket but the wilty celery and carrots still poked out.

“Don’t you dare throw out perfectly good food, Kevin,” his mother said firmly. She moved his hand, pulled out the aging veggies and waved them in triumph. “I can’t believe you were going to waste these!”

“We’re not throwing them in the garbage, Grandma. It’s compost. It turns into good stuff for the garden,” Ali piped up.

“The Island does have a pretty great composting program, mum,” said Ali’s dad. “It won’t just go into landfill.”

His mother sighed. “Ali, I’ve been composting since long before your father was born. Except we just called it being sensible. The hens got the potato peels and stale bread. The onion skins and cabbage stumps went into the pot.”

Ali couldn’t believe what she was hearing. “Wait, what? You made soup out of compost?”

“Not soup, dear. I boiled the leftover bits — carrot peels and parsley stems and whatnot — to make broth. I strained out the veggie bits and tossed them in the compost. Used the broth for soup.”

Ali looked at her dad, who nodded. “Your grandmother made sure we got every bit of use out of those vegetables. After they went onto the scrap pile they eventually turned into compost. We spread that on the garden to help grow more vegetables. And the soup was good, too!”

“Sounds like a lot of work,” Ali said. Seeing the look on her grandmother’s face, she quickly added “But very good for the environment. Our Green Club at school is going to have a vegetable garden this year.”

Her grandma rolled her eyes.

“Honestly! The way everybody talks about saving the planet, you’d think they invented the environment. If they talked less and gardened more — now that would be useful.” She pulled the carrots and celery out of the compost, rinsed off the coffee grounds and started peeling and chopping.

Ali opened the fridge again. “So, what are we having for supper, anyway?” Instantly, she wished she hadn’t asked. All her brain could think was, “Please don’t say leftovers! Please don’t say leftovers!”

Her dad pointed to some containers. “I was thinking of a reconstituted assemblage of the remnants of some previously enjoyed repasts.” Ali heaved a huge sigh. “Leftovers. I knew it.”

Her grandma threw an arm around her shoulders. “When you put it that way, it doesn’t sound so great. But I know how much you care about the environment. So, you should care about eating leftovers, too.”

Ali looked confused. “Grandma’s right,” her dad said. “I just read that Canadians waste more than half the food we buy. Imagine all the water and gas and energy that went into that food. Tractors to plant it. Irrigation. More machines to harvest it. Factories to process it and trucks to drive it to the store. All so that we can shove it to the back of the fridge and forget about it!”

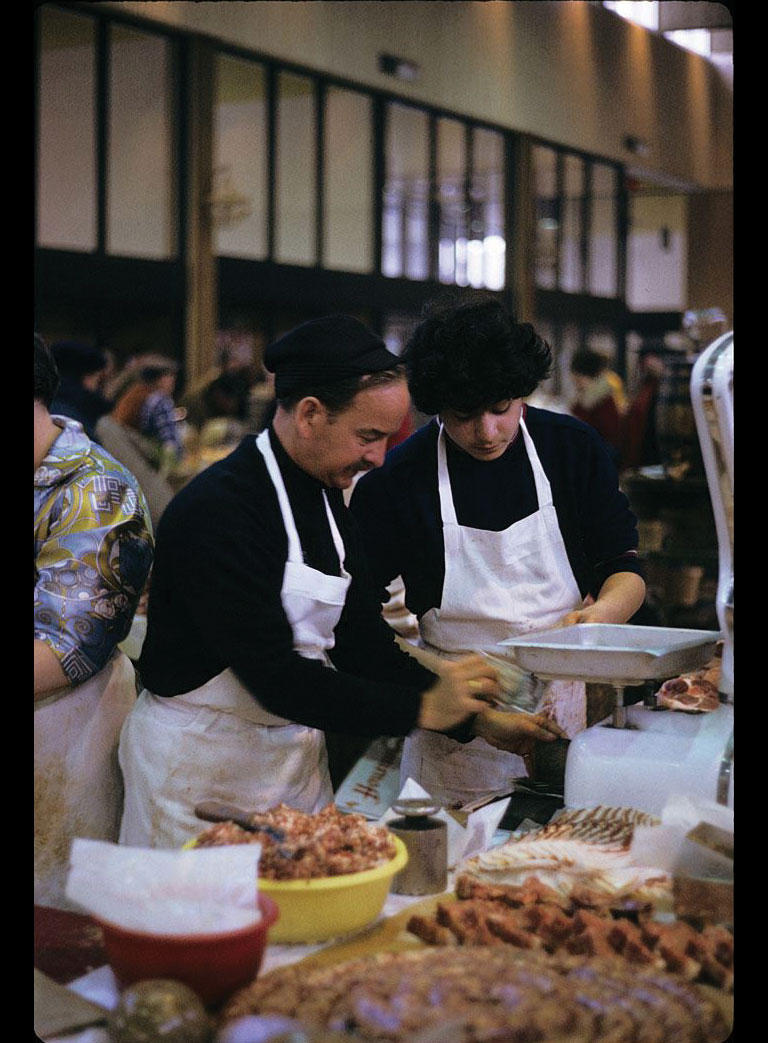

“Or let the store throw out the apples that aren’t quite perfect and the fish nobody bought,” added Ali’s grandmother. “It’s a terrible shame. We used every scrap of food because we couldn’t afford to buy more. And we certainly never left perfectly good food just sitting uneaten on our plates at a meal.”

Ali’s dad shrugged. “Sure, mum. But I’ve also seen you eat something just so it wouldn’t go bad. Eating food you don’t want is the same as wasting it.”

His mother shrugged. “You have so much more choice now — so many lovely things to eat. I just think that people forget to be grateful. They throw food out just because they don’t feel like eating it, and they let things go bad because they have too much.”

Ali looked at the fridge shelves loaded with fruit and cheese and, yes, leftovers. She looked at the open pantry loaded with pasta and cereal and snacks. She looked at her dad.

“You know what?” she said. “I think we could make a pretty great stir-fry out of that leftover chicken and the veggies.”

Her grandma flashed a big smile.

“Tasty and less waste-y! And we’ll be able to use up all that —”

Ali and her dad chimed in at the same time. “— perfectly good food!”

Food waste is a huge problem all over Canada.

More than 35 million tonnes of food produced here is lost or wasted every year. That costs the average Canadian household more than $1,700. Plus all that organic garbage releases gases like carbon dioxide and methane that cause climate change.

People on Prince Edward Island, like the family in our story, are some of the best recyclers and composters in the country. A 2014 study showed the average Islander kept 429 kilograms of waste out of landfills by sending it for recycling or composting. (That’s compared to a Canadian average of 255 kg per person.)

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive features both English and French versions of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids — 3 digital issues per year for as low as $13.99. Tariff-exempt!