Fuelling Anger

Eastern environmentalists chant, “End Fossil Fuels” and provide the votes for carbon taxes. Albertans, aware of what fuelled their prosperity — and the East’s industries, too — respond with: “Build that pipeline!” Ottawa leads a national response to a global pandemic — and a convoy organized by leaders from the West invades Ottawa as if it were the capital of a foreign enemy. Housing, health care, inflation, the environment, reconciliation — each issue seems to have Ottawa and the premiers caught up in wedge issues and mutual accusations. Politicians face hate slogans and threats every time they speak in public. National mandates, provincial sovereignty, firewalls: In Canada these days, division seems to make good politics. Is the country falling apart? Can’t anyone do anything without a fight?

As a student of Canadian history and a writer for Canada’s History, I have devoted a couple of books, a lot of writing, and a citizen’s concern to the political and constitutional history of Canada and its regions. Can constitutional and political history contribute anything helpful in these unsettled times? To say simply that times like these have been experienced before — well, isn’t that all one expects from a historian? But it is true: Canada has a long history of falling apart.

The disintegration of this unwieldy nation-state has been declared inevitable many times, back to the 1860s and up to today. Nova Scotians wanted to secede even before the ink on the Confederation documents was dry. The year 1885 saw the crisis over the hanging of Manitoba Métis leader Louis Riel. The First World War conscription crisis rocked the country in 1917. Then a constitutional deadlock set the provincial and federal governments against each other during the Great Depression of the 1930s. There have been innumerable plans for absorption into the United States, not to mention the Quebec independence movement from the 1960s onward and Alberta’s resistance to the National Energy Policy in the 1980s. Today the First Nations’ challenge to “our home on Native land” leaves Canadians to ponder who really owns this territory.

Yet Canada’s boundaries, its constitution, and its institutions have endured, flexing in response to challenges but never yet broken. History suggests the country can hold; accommodations can be made.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Conflicts over the exploitation of natural resources may be playing out today in debates over restricting fossil fuel extraction to limit greenhouse-gas emissions, but, as journalist and historian Mary Janigan points out in her 2012 book Let the Eastern Bastards Freeze in the Dark, different levels of government also came into conflict over natural resources in the 1920s — and successfully resolved their differences.

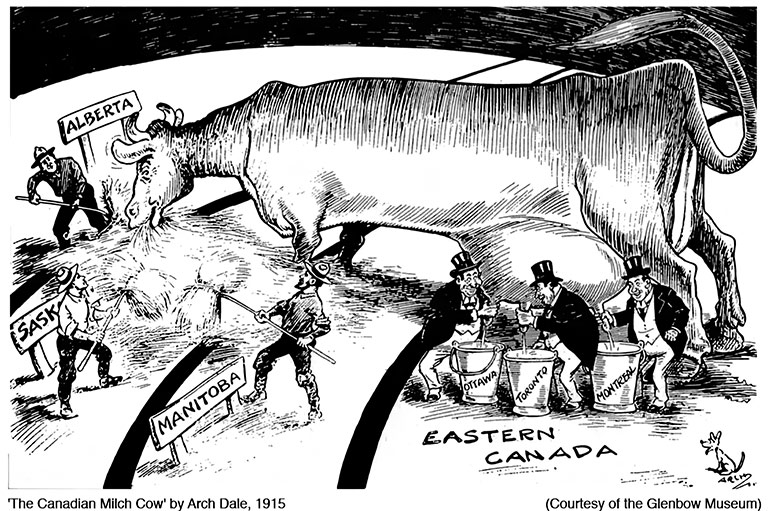

In the 1920s, the Prairie provinces struggled to gain control of their natural resources. The other provinces had always had that authority, but when Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan became provinces Ottawa denied them those powers. To their fury, the Western provinces couldn’t even get the other provinces to support their rights. The Maritime provinces needed money; they argued that their taxes had paid for the development of the West and that they were entitled to a share of the revenue from Western resources. Federal-provincial conferences on the question regularly collapsed in anger and frustration.

The Western claim to the same powers as all other provinces eventually prevailed. As Janigan observes, politicians and bureaucrats did manage to work out a solution. Despite all the headline fury, they worked together, and by 1930 the Western provinces controlled their own resources. In the next decade, when the great petroleum discoveries began at Leduc, Alberta, there was no doubt that the revenues were Alberta’s to control.

In her second book, The Art of Sharing, Janigan explores an even deeper dispute. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, provinces had the authority to help their citizens, but they lacked the money. Richer provinces struggled on, but resource-dependent provinces could not support schools, hospitals, social welfare, and other government services — the most basic functions of government. Ottawa, with its access to a broad range of revenues, could find the money, but the constitution forbade the federal government from spending on matters that were in the provinces’ jurisdiction: basically, on everything that was needed to fight the Depression.

During the late 1930s and 1940s, this fundamental constitutional mismatch was dumped into the lap of a Royal Commission. It was called Rowell-Sirois for its two leaders: Newton Rowell, an Ontario judge, and Joseph Sirois, a Quebec lawyer and scholar. The great Manitoba editor J.W. Dafoe (who was a commission member) and Premier Angus L. Macdonald of Nova Scotia (who was not) made huge contributions to Rowell-Sirois’s plan for constitutional adjustments: They proposed how federal tax revenues and provincial powers could work together to enable provinces to fulfil essential functions even in hard times.

At the time, Rowell-Sirois’s recommendations were rejected or just ignored, and attention turned to the Second World War. It was mostly the war, not the wisdom of statesmen, that put the Depression-scarred nation back to work and on a path to prosperity. Janigan admits that a failed Royal Commission from nearly a century ago sounds like one of the dullest topics possible. She points out, however, that an idea that Rowell-Sirois explored would become central to the Canadian federal experiment. This was equalization. The Depression had taught that the federation could not hold if a few prosperous regions could afford decent schools, hospitals, highways, and other public services, while the others simply could not. “Every federation in the world has some kind of equalization system, except the United States,” Janigan told me.

In the prosperous 1950s, Rowell-Sirois’s case for equalization returned to the Canadian agenda. No provincial government would ever have to contribute. The federal government accepted that it would cover the full cost of equalization. It was Liberal Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent who presided over the negotiations and got equalization passed into law. Conservative John Diefenbaker, who succeeded St. Laurent, sent out the first equalization cheques soon after taking office. “How long Canada took, and how stubborn the premiers were in many places!” marvelled Janigan.

Advertisement

Equalization transformed provincial governments across Canada. Until the 1950s, most provincial governments were small, lacking in civil-service expertise, and limited in the programs they could afford to run. With equalization, even the poorest provinces could pay schoolteachers adequately, build critically needed highways and hospitals, and support their neediest citizens, without going cap in hand to Ottawa in every downturn. Despite all the subsequent controversies, Janigan remains convinced that equalization became “the improbable glue that holds the nation together” — the cornerstone on which today’s active and powerful provincial governments stand.

In the twenty-first century, with our glaciers melting, our forests burning, and our weather reports turning into terrifying threats, no topic looms larger in the national conversation — or divides the regions more — than climate change. It’s an issue that once again catalyzes the issues of resources, revenues, and regional divisions. If dealing with climate change requires a sudden retreat from fossil fuels, must Alberta go back to relying on, say, cattle ranching as its leading economic sector? No wonder Albertans have seen in federal climate policy both a raid on their resources and a threat to their prosperity. That’s no formula for peace and tranquility.

Trevor Tombe, an economics professor in Calgary, knows that political conflict over economic policy “really is a feature of Canada’s economy and has been from the very beginning.” Our regions have differently structured economies, he observes: Tensions between federal policy choices and regional economic priorities must be expected. As an example from history, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s National Policy in the 1870s favoured tariffs to protect Canadian industry (mostly located in Ontario and Quebec) but added to the equipment costs of prairie farmers and hobbled the shipping of the free-trading Maritimes.

Tombe counsels optimism. This kind of dispute, he said, “is something that we have managed from the very beginning. And I think that suggests that we will manage this time as well.” Fury in the daily media is not necessarily a guide to long-term possibilities.

Tombe urged me to see that Alberta’s economy is less dependent on oil and gas than many people think. “It is a large industry,” he said. “But it is less important as an employer here than the finance industry is in Ontario. And the amount of GDP accounted for by British Columbia’s real estate sector is — up until, say, this year — larger than what oil and gas is in Alberta.”

Oil revenues are central to Alberta’s budgeting, with huge deficits alternating with huge surpluses as global oil prices surge and collapse, he acknowledged. But, although the oil-and-gas sector accounts for about twenty-one per cent of Alberta’s annual GDP, the province also has many other strengths. It can diversify its sources of revenue beyond oil- and-gas dependence, notably to innovating in alternative energy sources. “I’d say climate policy is not something that poses some kind of existential challenge for Alberta. That’s why you see a lot of major oil-and-gas companies supporting policies like carbon pricing. Lowering our emissions is not something that turns Alberta’s economy into a have-not province. Far from it.”

Chris Turner, another Calgarian and a journalist who specialises in global climate policy, has been observing climate conferences and technological innovations around the world for years. The result is a 2022 book, How to Be a Climate Optimist. Turner is looking at the world, but his ideas apply directly to the climate-versus-economy concerns of Canada and Alberta.

Climate despair, Turner suggests, comes from endlessly hearing that to prevent climate catastrophe we must stop all the activities we value and give up all the things on which we rely. Turner argues instead that we should understand that, above all, the climate crisis is defined by sources of energy. And our sources of energy are changing faster than we realize. In fact, he writes, we have heard the promise of solar energy for so long that we may have failed to notice that the technology required for cheap, abundant solar-powered energy generation is already here.

Although solar power at present accounts for only a small fraction of worldwide energy production, it is rapidly growing just as technology is improving and the cost of solar generation is dropping. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), worldwide solar generation increased by twenty-six per cent in 2022 over the previous year, and solar is expected to overtake both natural gas and coal as a source of power by 2027. Solar already outcompetes fossil fuels on price: In 2010, the lowest price predicted for solar power in 2020 was about twenty-two cents per kilowatt-hour. The real price in 2020: five cents per kilowatt-hour. The IEA’s June 2023 Renewable Energy Market Update notes that “solar PV [photovoltaics] and onshore wind remain the cheapest option for new electricity generation in most countries.”

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

After decades of pessimism, Turner believes that the world can reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 using the solar technology we already have. His conclusion: We do not need to ban fossil fuels. The world economy is going to turn to renewable solar power, high-efficiency batteries, wind tech, and probably hydrogen energy, too — not because oil will be banned but because the new sources will be cheaper, more abundant, and more efficient. Some polls suggest that most Canadians already expect their next car purchase to be electric or hybrid gas-electric.

Does all this mean something for Canada’s East-West tensions? Surely it does. One perspective on that comes from another prairie expert. Vaclav Smil — the University of Manitoba scientist who is billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates’s go-to expert on climate futures — points out in his 2022 book How the World Really Works that fossil fuels are not going to vanish overnight. They will have a long tail, even as low-carbon energy sources take over.

Turner cites Smil’s work as support for his growing confidence that pipelines and climate action are compatible. Turner suggests the federal government believes that too: It is currently building the Trans Mountain pipeline from Alberta to the Pacific coast. That is, oil, including Alberta’s oil, will still be needed even as fossil fuels cease to be our primary source of energy and as solar technologies continue to rise among Alberta’s growth industries.

Climate crusaders and oil-industry advocates will no doubt be shouting at each other for a long time to come. Alberta and Ottawa will probably still be fighting over energy policy in 2050; it’s part of their job. But Trevor Tombe and Chris Turner, both Albertans, want to tell us that the energy transition now in progress need not be a disaster for Alberta, nor something over which to impoverish the province or tear apart the country. Solutions are available as the province makes a gradual transition from fossil-fuel extraction to the production of alternate energies.

Will solutions be achieved? The greatest hurdle may lie more in the general political dysfunction in East-West relations than specifically in Alberta’s uncertain ability to thrive in a low-carbon world. “Number one, the discourse has to remain respectful, no matter how disturbed people get,” Mary Janigan told me. “And number two, it’s not in anyone’s interest to twist the facts.” There was a lot of heat in East-West confrontations from the 1920s to the 1950s. But in the records of those crises Janigan read of politicians and civil servants who argued hard but respected facts. “I didn’t see too many incorrect assertions when I read the transcripts of those federal-provincial conferences. And when someone was inaccurate, they took each other on. It’s the mechanics, the process of federalism, that we do have to work it out.”

Trevor Tombe was more blunt: “Canada’s very diverse. Tensions are unavoidable, and natural, and okay to exist.” But he faults federal politics and politicians for not speaking to the national interest. “Our politics today really does slice and dice the electorate, and I fault all parties. No one’s really speaking about the country and its overall interests or trying to find things that are common across regions.... What we need are voices that can speak to not just regional interests and not just partisan interests but to broader national ones.”

Michael Chong, Member of Parliament for Wellington-Halton-Hills in Ontario, has some first-hand insights into the problems of Canadian political culture. He is best known for his Reform Act of 2014, in which he persuaded his fellow MPs to give a little more authority to backbench MPs, including the power to remove their leaders from office.

Chong wonders whether the Canadian Parliament can effectively balance regional interests and the national interest. He links its failure in this regard to the fact that ordinary MPs no longer believe they can effectively wield the tools of Parliament. MPs, he said, “have lost the right to speak in the House of Commons” unless given permission by their leader to do so. “It sounds astounding as I say it, but that is a fact.” Because of the unique centralization of power in party leaders in the Canadian version of parliamentary democracy, Chong argues, debate doesn’t matter anymore in the House of Commons.

“The votes are preordained,” he said, the results known before discussion even begins. There is no point in applying reason or evidence to persuade one’s fellow MPs, whose minds have been made up for them. So Commons debates are about performance and filibuster. Our political parties “become their leaders, in a way that you do not see in other democracies,” said Chong.

Social media have recently done much to turn online discussions of politics into shouting, bullying, and abuse. But in effect the House of Commons has been tolerating similar tactics since long before the Internet. In the Commons chamber, cheering for the leader and harassing the other side have become the only work most MPs have. Parliamentary debate only works if MPs who hear persuasive arguments can have enough influence to change their leaders’ minds, and if their yea or nay can make a difference.

Chong suggests that when parliamentary debate is stifled, national issues become inflamed instead of being negotiated. A caucus of representatives can change its mind, but premiers and prime ministers must always strike poses of uncompromising strength for fear of being seen as weak. When every Canadian issue becomes directly linked to individual party leaders’ permanent need to be strong, the space for respectful discussion and fruitful compromise shrinks to nothing. “The East-West divide becomes a characteristic of the parties,” he explained. The Conservative Party becomes the vehicle for Western grievance, while the Liberal Party becomes a vehicle for deafness or resistance to Western grievance, because of the leaders who control those parties.

Respect, attention to national perspectives, and reasonable accommodation of differences — the crying needs outlined by Janigan and Tombe — are casualties of the way our political parties have restructured parliamentary representation and parliamentary debate. “If you want it to be less vicious and more substantive, then one of the things that needs to change is MPs have to be given meaningful work rather than repeating vacuous talking points.”

Advertisement

Chong locates our Canadian dysfunction in a crisis of political culture as much as in particular issues that divide East and West. How can we create a political culture in which East-West tensions can be, if not solved, at least addressed in ways that are less toxic?

First, perhaps we need to accept that there will always be regional tensions and federal-provincial divisions in Canada. Canadians may at times be inclined to dismiss our constitution as a relic of a distant, irrelevant past. But the foundation of the constitution of 1867 was the federal concept, which provided for provinces and provincial governments within the federation and gave them authority for matters of a local and private nature.

In 1867 Canadians were expected not to look to Ottawa for everything. “The provinces are not … subservient to the Parliament of Canada; each body is independent and supreme within the limits of its own jurisdiction,” declared Oliver Mowat, who helped to draft the constitution and then served as premier of Ontario from 1872 to 1896. Not only were provincial governments empowered to act independently in the matters the constitution entrusted to them, but those governments could also represent their regions and their citizens in standing up to the national government when its policies inconvenienced or offended local interests. Federalism was not invented to put an end to regional differences and federal-provincial disagreements; it created a framework in which those disagreements could be discussed and managed.

But that process for managing tensions presumes that both levels of government will stay within their lanes — with provincial and federal governments each taking care of the responsibilities assigned to them by the constitution and respecting the boundaries between them.

This may have been easier in the past. In Canada’s early years the division of powers was stark and clear in many fields. Education, health care, social welfare, and other matters were clearly provincial responsibilities. But early on, the provinces left the costs of these matters to charity or to religious institutions. No province spent a lot on them. The poorer provinces could barely afford to provide basic social services even in good times, let alone in the depressed 1930s.

Today the provinces are no longer poor relations. Resource revenues and, where needed, provincial income taxes have expanded to meet the rising costs of social programs. Provinces in need have access to equalization payments from the federal government. And many provincial services, like medicare, have become shared-cost programs where the provinces still run the programs but Ottawa contributes funding, subject to certain conditions.

Perhaps shared-funding agreements have blurred our sense of the traditional division of powers and responsibilities between Ottawa and the provinces. Today many Canadians seem to look to Ottawa for action whatever the problem. Too few nurses, hospital beds, or ambulance drivers in provincial health-care systems? We think of medicare as a national commitment and blame Ottawa for the shortcomings. Problems in the schools and the universities? Education remains a provincial responsibility, but Canadians call for national mandates in learning. A shortage of affordable housing? It’s essentially a provincial matter, again, but we look to Ottawa to solve the problem or take the blame.

In that climate, it may be natural for provincial politicians to follow the trend. They can always blame Ottawa for underfunding health care, or universities, or housing, instead of being held accountable for their own responsibilities. East-West tensions and federal-provincial relations might be more easily addressed if Canadians retained the habit of holding provincial governments accountable for provincial matters and federal governments accountable for federal ones. As some of the wealthiest provinces, the Western provinces could demonstrate to the country the best health-care programs, the most prestigious educational institutions, the most effective systems of urban government — and gain both confidence and influence in their dealings with the rest of the country as a result. We would still have East-West tensions, but they might be better defined and more peaceably managed if citizens everywhere held both federal and provincial representatives accountable within the boundaries of their specific responsibilities.

Michael Chong points out how top-down and leader-centred Canadian politics — both federal and provincial — has become over many decades. Our leaders are no longer chosen by their fellow elected politicians or held accountable by the representatives we send to Parliament and the legislatures. Cabinet ministers no longer run their own departments, let alone wield a restraining hand on leaders who long since ceased to be first among equals and have grown into virtually presidential figures.

In the past, prime ministers had cause for moderation in negotiations with premiers. Influential MPs and powerful cabinet ministers would vigorously represent their provinces and stand up against any leader who attacked them. Similarly, premiers dealing with Ottawa had ambitious ministers and backbenchers prepared to challenge them if they failed to deliver results. Deep in our parliamentary history, and still common in other parliamentary systems, a vital function of legislators has been to serve as a check on their leaders. Today, however, a Canadian premier or prime minister may often find there is no downside to ramping up tensions with the other level of government.

Mary Janigan’s histories showed me that, over a century and more, Canada has been able to make immense changes in how it provides and pays for the services Canadians want and require. Trevor Tombe and Chris Turner gave me some confidence that the energy issues that have seemed most threatening to Western livelihoods and Western prosperity can be dealt with more successfully than we often imagine.

Because we are a big country with profound regional distinctions, we will always have East-West and federal-provincial tensions. But to handle those tensions, and to make regional rivalries a source of strength and pride rather than anger and frustration, we need to rethink how we imagine and talk about regional and national responsibilities. Even more, we need to revive parliamentary traditions. Strong leaders who refuse to consult or to compromise are a dime a dozen. What’s missing are vigorous, confident parliamentarians able to rein in the leaders and stand up for tolerance and accommodation.

While we celebrate Earth Month every April, it's important to remember our impact on nature and the environment every day. The First Nations, Inuit and Metis of Canada understood the importance of living in harmony with nature, and shared that knowledge with new arrivals as early as the 15th century.

If you believe that stories of climate and nature, and their impacts on early Canadians, should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement