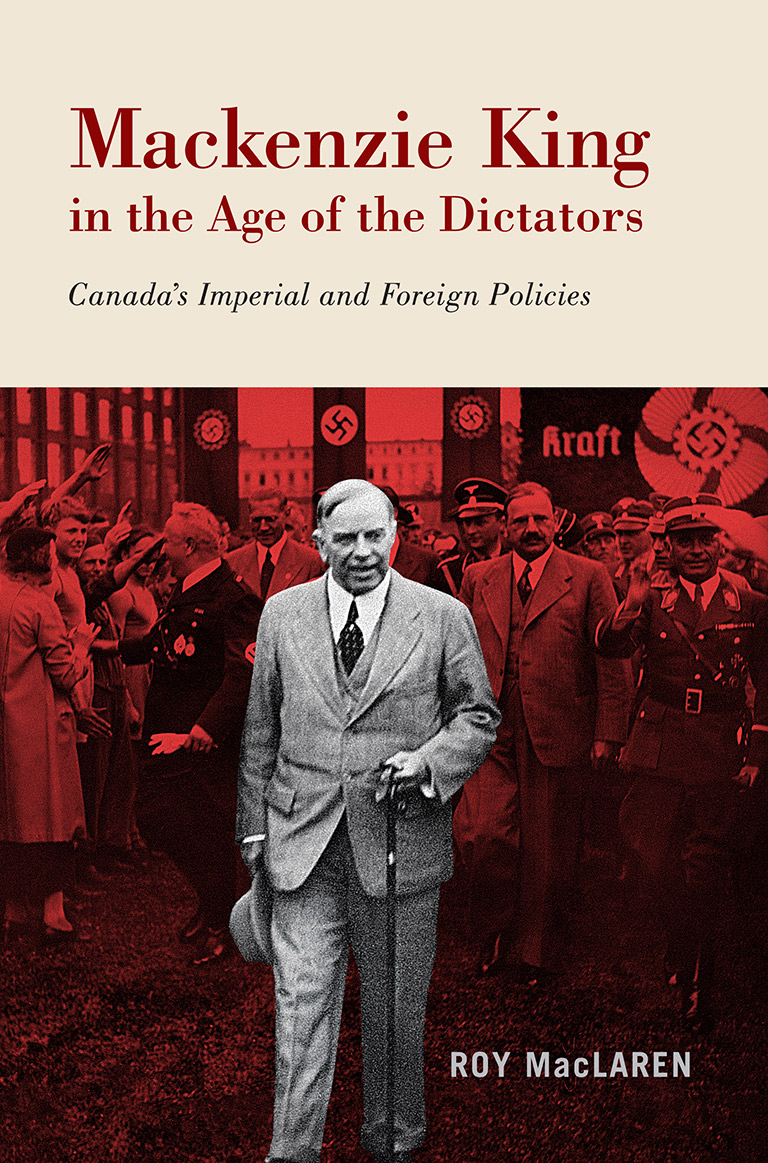

Mackenzie King in the Age of the Dictators

Mackenzie King in the Age of the Dictators: Canada’s Imperial and Foreign Policies

by Roy MacLaren

McGill-Queen’s University Press, 354 pages, $34.95

A double review with

Four Days in Hitler’s Germany: Mackenzie King’s Mission to Avert a Second World War

by Robert Teigrob

University of Toronto Press, 312 pages, $32.95

That Canada’s longest-serving prime minister was one extraordinarily odd duck is beyond dispute. A steady stream of books about William Lyon Mackenzie King and his peculiarities has mined the stupendous motherlode of eccentricity that is the diary King kept from 1893 until three days before his death in July 1950.

Military historian C.P. Stacey, himself one of those early miners as the author of A Very Double Life: The Private World of Mackenzie King, has called the King diary “the most important single political document in twentieth-century Canadian history” and said its contents will occupy researchers of many types “for generations to come.”

That prophecy, made in 1976, has indeed come true, the most recent proof being the nearly simultaneous publication of two very different but equally expert and fascinating examinations of King’s handling of Canada’s foreign policy in the period leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War.

Both works, Mackenzie King in the Age of the Dictators, by Roy MacLaren, and Four Days in Hitler’s Germany: Mackenzie King’s Mission to Avert a Second World War, by Robert Teigrob, rely heavily on the King diary. Indeed, without access to the prime minister’s private thoughts, neither book would be as insightful, as cringe-inducing, or, likely, even possible.

The two books, both brimming with rigorous, original research and startling detail, actually work very well as companion pieces. Whereas MacLaren, a former diplomat and federal cabinet minister, tracks in meticulous detail King’s approach to Canada’s foreign policy, from labour minister in Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government to his interwar stretch as prime minister, Ryerson University history professor Teigrob focuses more narrowly, and with exciting, satisfying depth, on King’s four-day visit to Nazi Germany and his controversial one-hour meeting with Adolf Hitler in June 1937.

Beware, though. Those only casually acquainted with King’s “double life,” notably his belief in spiritualism and his communication with dead family members, pets, and historical figures, should brace themselves for a shocking immersion into the bizarre mind of the man who led Canada for twenty-one years, including, to his qualified credit, through the challenges of the Second World War.

MacLaren provides a detailed history of King’s approach to pre-war foreign policy, which, in sum, was: “better to say nothing about the dictators and hope for the best.” King certainly did not “say nothing” to his diary about dictators and about all manner of other matters that were on his mind. We learn, for example, that King had an abiding fear of Americans, such as President Theodore Roosevelt, wanting to take over Canada; that he felt a kinship to Hitler because of the two leaders’ attachments to their mothers; and that he saw himself on a divine mission, fulfilling the destiny of his rebel grandfather and namesake, William Lyon Mackenzie, in trying to bring Britain and Germany together to avoid war.

The MacLaren book is particularly valuable for its examination of pro-fascist currents in Canada, one example being the Roman Catholic church in Quebec’s support of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini because of his recognition of the Vatican as an independent state and his fervent anti-communism.

And yes, both authors conclude that King was a bona fide anti-Semite, neither of them granting a man of his education and experience a pass for being a product of his xenophobic, intolerant times. Certainly the most infuriating and tragic aspect of King’s wilful denial of well-documented Nazi evil is his attitude towards Jews, which led to Canada’s refusal to accept significant numbers of refugees from the mounting Holocaust hell.

This was consistent with King’s strategy, which MacLaren lays out clearly, of viewing events on the international stage from the perspective of their impact on domestic electoral politics. Another example is King’s loathing of the collective-security provisions of the League of Nations, which he thought might ensnare Canada in a war in some distant land. King’s “muddling” played a critical role in that body’s failure to stand up to Mussolini and Hitler, thereby empowering the fascist duo in their territorial ambitions.

King’s “cheerleading” for Hitler’s regime got a tremendous boost during his tour of landmarks of the Nazi “miracle,” as Teigrob recounts in riveting detail. The photographs tell a very chilling story as well, especially one that shows King sitting proudly in Hitler’s seat at the All-German Sports Competitions while surrounded by Nazi bigwigs in full swastika-studded regalia.

Teigrob describes how King got a last look at some of the top Nazi henchmen he considered friends when he spent a day at the war crimes trials in Nuremberg in 1946. On the same visit, King, who never failed to inform his Nazi hosts that he was born and raised in the German settlement of Berlin, Ontario (now Kitchener), paid a return visit to the old-country Berlin to view the devastation wrought on the capital of the Third Reich by Hitler — the man, King had confided to his diary, whom he believed “might come to be thought of as one of the saviours of the world.”

This sentiment — along with much, much more that is unearthed in these substantial, important books — casts King as something much more dangerous and disturbing than the Weird Willie persona of a creepy, dithering dolt. If he could speak from beyond the grave, King would be displeased, but he would likely do nothing.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement