From Rink Wars to Ink Stars

Hockey illustrations go back as far as the game itself, and — along with the daily newspapers in which they regularly appeared — they’ve played central roles in both popularizing and commenting on the sport. In his book Picturing the Game: An Illustrated Story of Hockey, author and television producer Don Weekes presents hundreds of images that range from unattributed early drawings of game play to mischievous editorial cartoons that satirize the people involved in hockey as well as Canadians’ devotion to the game.

Weekes writes that, after seeing a decades-old hockey-related editorial cartoon by the Vancouver Sun’s Len Norris, and then learning the amazing story behind it, he became “fully invested in telling real hockey stories through the efforts of game illustrators and cartoonists whom we wouldn’t otherwise read about or know of.” It was the outset of a years-long project during which he discovered numerous examples of their remarkable work — including from the era when technical limitations meant that camera technology was unable to capture the speed and excitement of the game on ice.

Cartoonists also portrayed action off the ice, showing hockey audiences and team owners, as well as players both training for matches and celebrating their successes — or in the wake of defeat. According to Weekes, the images in Picturing the Game present “a funnier, more personal version of reality,” celebrating the sport and poking fun at it while showcasing the talents of generations of illustrators.

In the following excerpt he tells about the early years of competition for hockey’s top prize, the Stanley Cup, and shows how illustrators not only shared the excitement of those events but helped to shape Canada’s national winter pastime.

Chasing Stanley

by Don Weekes

The ancient play between two ancient hockey clubs in February 1889 is ancient history today. For whatever reason, its historical significance is seldom recognized in hockey’s timeline of momentous events. The few thousand fans who crammed themselves into Montreal’s Victoria Skating Rink had no inkling of what this particular game would mean to sport. Local reports wrote in great detail of the Montreal Wanderers’ 2–1 win against the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) and of the “surging, swaying mass of dense humanity [that] … packed the gallery and promenades of the rink.” It was the first contest of the much-anticipated championship series at that year’s Montreal Winter Carnival. That alone wasn’t what stirred the crowd, or what makes this match of such great consequence today.

Victoria Rink was appropriately festooned with decorations and “flags of various nations” to greet one highly distinguished first-time observer of hockey. Given the occasion, his arrival was heralded by a fanfare of trumpets. Each player lined up at centre ice. The band played “God Save the Queen.” Then, Victorias captain Jack Arnton called for three cheers, and everyone “join[ed] in the general enthusiasm” to welcome His Excellency, Frederick Arthur Stanley, Lord Stanley of Preston.

It was Stanley’s first winter in Canada. He had arrived eight months earlier from England to begin an eventful five-year term serving as the sixth Governor General of the Dominion, the country’s head of state, and its principal liaison to Britain and the Empire. Based on accounts, Stanley attended, and in some cases participated in, many of the carnival’s activities. He was immediately taken by hockey’s rush of play and its enthusiastic crowds. “His Excellency expressed … his great delight with the game of hockey and the expertness of the players.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

For the Stanleys, the sport would become a family affair. Several of Lord Stanley’s sons and his daughter Isobel took up play in informal contests at the Rideau Hall rink in Ottawa. Their active participation helped kindle hockey’s popularity, and that first game made a lasting impression on Stanley, as he would forever on its play.

Lord Stanley proved an ideal benefactor. He possessed a fondness for athletics and the principled credentials as Queen Victoria’s representative in Canada. His motivation to establish a championship trophy arose from an obligation to nurture that generation’s sense of nation building. But Stanley also saw a chance to improve the rudimentary challenge system of the AHAC (Amateur Hockey Association of Canada). The Montreal-based organization required that a championship team face a new challenger in each game for the title. Even though Ottawa was champion six times, winning the title after each of six wins throughout 1891–92 (four against Montreal), the AHAC still awarded that season’s final league championship to the Montrealers because they beat Ottawa 1–0 in the last challenge on March 7.

The baffling challenge setup and the AHAC’s final ruling likely troubled the fair-minded Stanley. About a week later at a raucous banquet feting the Ottawa team at Russell House Hotel in Ottawa, Stanley, through an aide, announced his new trophy and suggested an alternate, more sportsmanlike format to determine the season’s champion. At the next league meeting, in December 1892, the Ottawa Hockey Club proposed a “championship series” for the five teams in an eight-game season. The club with the most victories would be declared the titleholder.

This idea wasn’t entirely original. On previous occasions in 1890 and 1891, the Dominion Illustrated had called for “a play off at the end of the season for the championship of the Dominion.” Lord Stanley would make the notion real with his Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup. That spring, in 1893, the Montreal AAA was crowned its first recipient. By then, Stanley’s fiveyear posting as the Queen’s chief agent in Canada was over. He returned to England, neither a witness to any competition for his cup nor aware of how influential his silver bowl was in shaping a young country’s ice game.

Hockey has never monopolized the nation’s sporting landscape, but once organized the game found itself at home in our winters and its sense of purpose in the Stanley Cup. Awarded originally to promote amateur play, Lord Stanley’s silverware quickly became hockey’s greatest alchemist. It not only served an emergent Canadian nationhood; his modest bowl brought the game athletic validation and, in no time, attracted the public’s fascination and the purse strings of promoters everywhere.

The stiffest competition to Montreal’s domination of Stanley Cup play during its first decade didn’t come from larger populations but from the boomtown plains of Manitoba. The bleak and inescapably cold winters were ideal for making ice hard and young men into rugged sportsmen. It also made the Winnipeg Victorias Stanley Cup champions. A meeting place of traders who once plied its rivers and tributaries, Winnipeg’s punishing geography was, as American writer “Studs” Terkel reported on pre-modernity, a place where “One had to stand up and fight — fight the weather, fight the land or fight the rocks.” This homesteader resolve to civilize Canada was the genesis of early Western temperament in team play. As if the frozen prairies had birthed hockey’s spirit, the Vics adopted a belligerent style all their own.

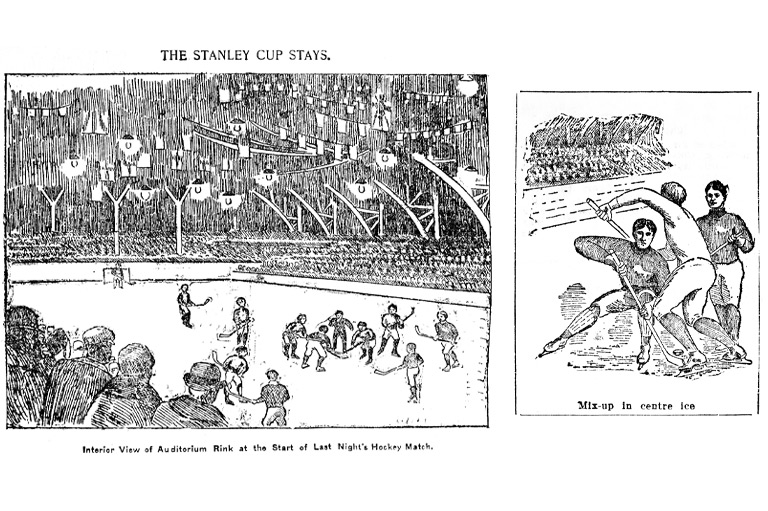

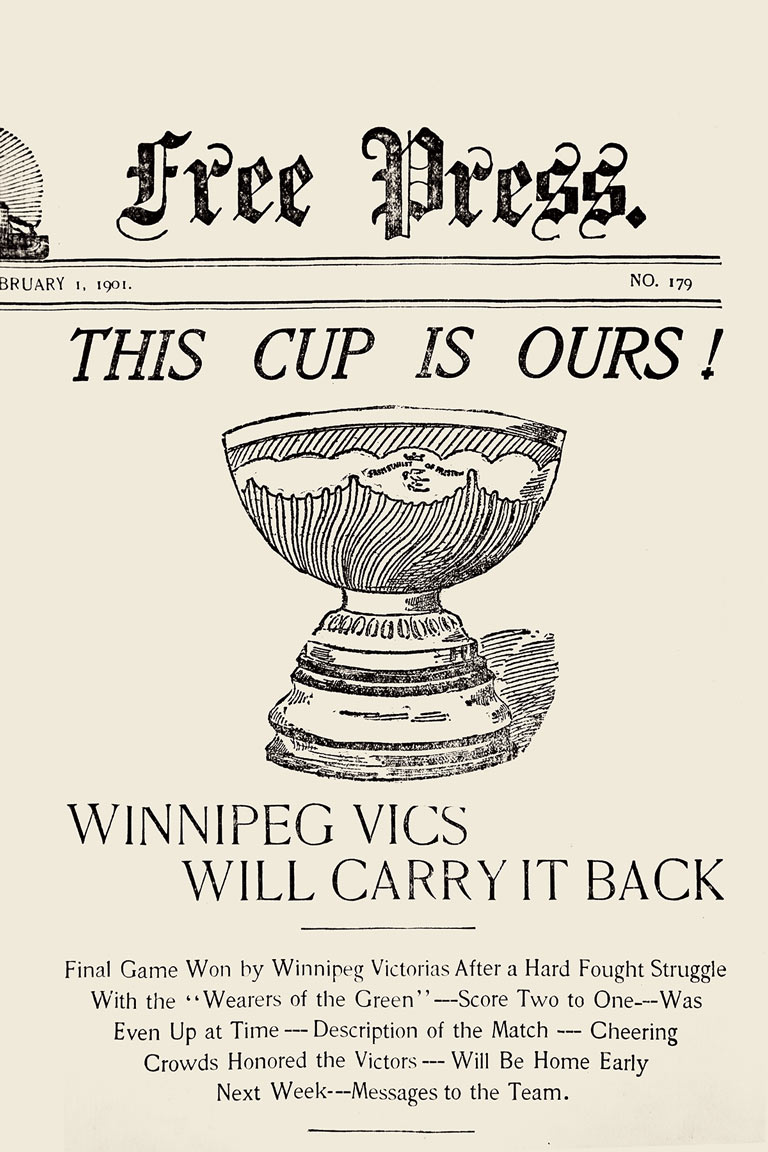

The newspaper coverage was no less bracing. After Winnipeg’s 4–3 win against Montreal in Game 1 of the 1901 cup challenge, the Manitoba Free Press headlined “The Vics After That Coveted Hockey Cup” under its main banner. It was a front-page rarity for hockey in a major Canadian daily. That Wednesday was no slow news day — not with breaking reports of the death of Queen Victoria (after whom the Winnipeg club was named).

Sketches of Burke Wood and future Hall of Famer Dan Bain highlighted the match’s account, the Vics’ win coming on a last-minute goal by Wood. “It took so many of the boys in green [Montreal] to watch Bain that Wood was left unchecked. The result was when he got a nice pass from [Tony] Gingras he landed the puck between the posts.” Following Winnipeg’s bestof- three sweep with Game 2’s 2–1 overtime victory, the Free Press’s front page said “This Cup Is Ours!” above a large sketch of the trophy.

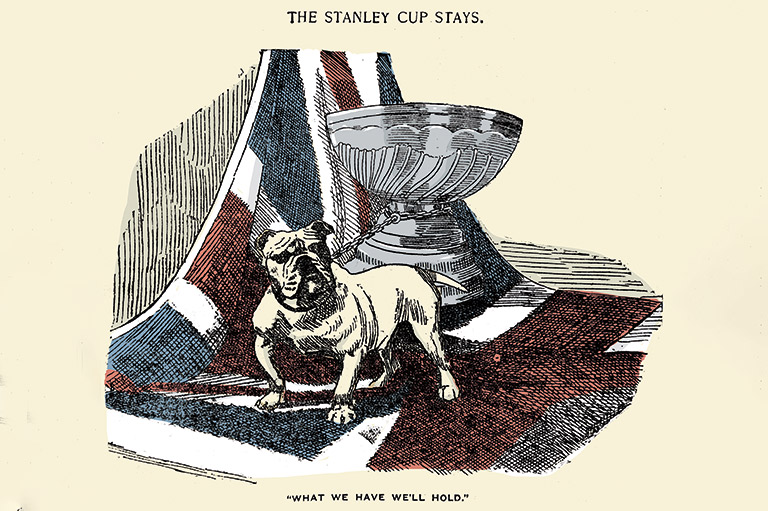

The next season, during Winnipeg’s 1902 cup challenge versus the Toronto Wellingtons, the paper blanketed its coverage with some of the earliest action scenes of Stanley Cup play. After Winnipeg won, the Free Press devoted half its front page to the game’s report and the illustration The Stanley Cup Stays. The sketch and the quote “What We Have We’ll Hold” were quite familiar to British Empire subjects. They referenced Maud Earl’s painting of the champion bulldog Dimboola alongside a draped Union Jack, which was immortalized in propaganda posters to promote the Boer War of 1899–1902. Earl was a renowned, British-born, American canine artist. Her image of Dimboola was so well-received that the bulldog became one of Britain’s most familiar stereotypes.

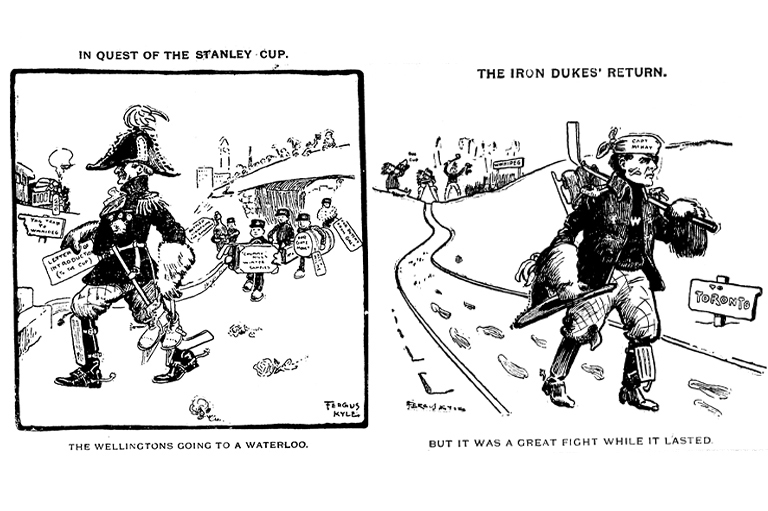

The January 1902 cup challenge marked Toronto’s first ascent into top-ranked play. The Wellingtons, known as the Iron Dukes, were two-time senior OHA (Ontario Hockey Association) champions, with more ambition than experience. Few photographs of their three-game series against Winnipeg survive. A better chronicle of events may be three J. Fergus Kyle illustrations that endure as a major advance in the visual documentation of playoff hockey.

“A born cartoonist,” Kyle themed his first drawing on Toronto’s unseasonably warm weather during January training workouts. No artificial ice meant dryland drills on turf, which proved a “great drawback to the hockeyists,” conceded Toronto’s Daily Star. Still, they were “not to be overlooked as possible winners of the trophy.” Veteran hockey watchers in Manitoba and Quebec were less optimistic. The Toronto squad had a short history in senior hockey, it iced few recognizable stars, and no Ontario team had ever claimed a national crown. Against the highly skilled Victorias, the Iron Dukes were, at best, Cinderellas.

Kyle’s second cartoon reflected his newspaper’s confidence in Toronto’s chances. The day before their departure for Winnipeg, he drew The Wellingtons Going to a Waterloo, a play on words that references the Duke of Wellington’s victory over Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. As Kyle saw it, Winnipeg was the routed French armies, and Toronto was the victorious British and Prussian forces. However, the Wellingtons’ valiant play would falter, losing by 5–3 counts in consecutive contests. “We were fairly beaten,” admitted captain George McKay. “We played as hard as we ever played in our lives, but the checking and the bodying was much harder than we were accustomed to, it was fierce … yet it was fair.”

This magnanimity of amateur spirit aside, in truth the Wellingtons limped away with numerous players hurt. McKay himself was forced to quit midway through Game 2 after “several hard body checks put him out of business.” Kyle’s final cartoon, The Iron Dukes’ Return, bookended his Waterloo theme. This time a battle- scarred McKay departs Winnipeg in defeat. He holds his navy cocked hat in hand out of respect to his victorious opponents.

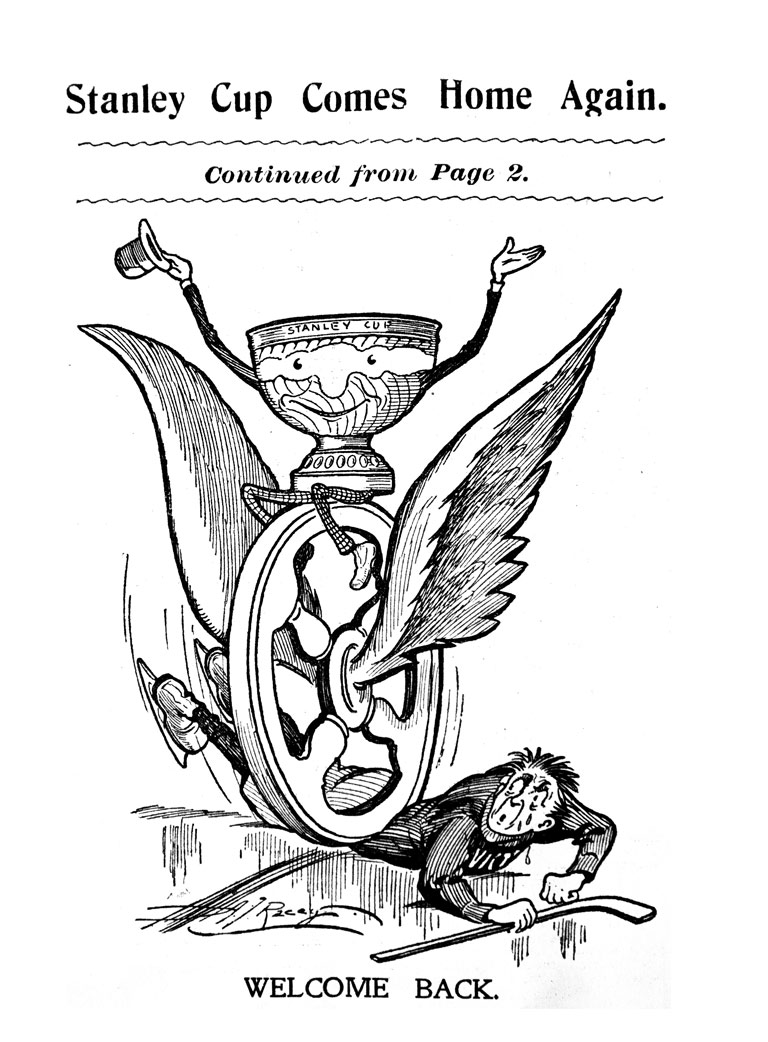

Two months later, in March 1902’s Stanley Cup challenge, Winnipeg faced an entirely different contender in the Montreal AAA. Perhaps travel-weary, the AAA lost the first match 1–0, but the team rebounded with a convincing 5–0 win in Game 2 before four thousand fans, some paying twenty-five dollars per seat. During the cup decider two nights later, the AAA scored twice in the first eleven minutes. After that, the tenacity of Montreal’s smaller defenders dominated play, famously stymying repeated blitzes by the bigger Winnipeg team. Reporters christened the AAA the “Little Men of Iron.” The moniker, along with Toronto’s Iron Dukes and Ottawa’s Silver Seven, became old-time hockey’s most familiar nicknames.

Upon their return to Montreal, Arthur Racey illustrated the cup in human form, with spindly arms and legs that straddled the AAA’s wingedwheel emblem. Political cartoonists had long personified the world as a human figure with the globe head. Racey’s Welcome Back may be first to adapt this cartooning staple to hockey.

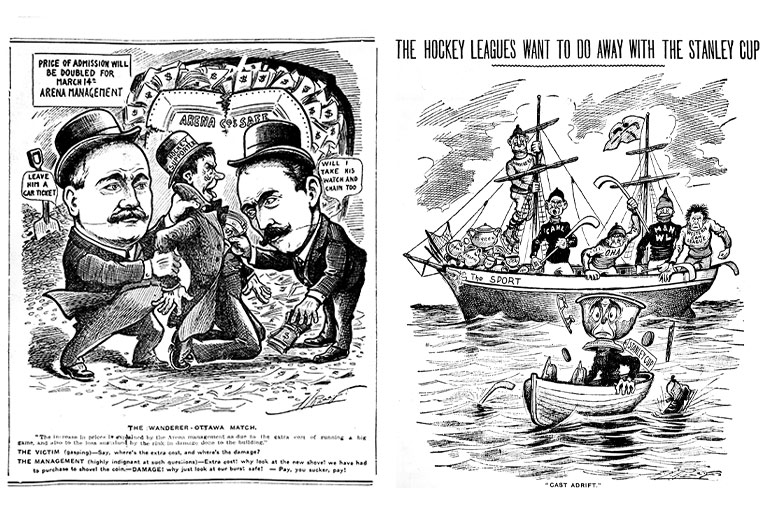

Most early drawings of cup competition amounted to crude illustrations of play or player headshots. On occasion, other newsprint artwork, such as Kyle’s portrayals of the 1902 Toronto Wellingtons, surpassed the standard fare in both idea and draftsmanship. More provocative interpretations came from the imagination of Arthur Racey. When others treaded prudently after complaints of ticket-price gouging by arena managers during 1906’s Stanley Cup, Racey drew a fan on bended knee, being strong-armed and bullied to “Pay, you sucker, pay!” It may appear facile today, but back then no one dared to graphically ridicule game concerns so sharply. ...

The Silver Seven was officially the Ottawa Hockey Club. Its lineage predates most teams, except McGill University, the Montreal Victorias, and the Quebec Hockey Team. Ottawa HC was a founding member of the first championship league, the AHAC, and had won OHA titles in the circuit’s first three years from 1891 to 1893. A decade later, during several magical winters, Ottawa rose to fame as the invincible and much-feared Silver Seven. Chasing cup challenges worth thirty-day reigns, Ottawa — the first cup winners from Ontario — went three for three, winning championships in January, February, and March of 1904. In their unfailing pursuit of Stanley, and owing much to the headlong rushes and wounding bodychecks of Frank McGee and Harvey Pulford, they ruled uninterrupted through nine challenges from 1903 to 1906.

The notoriety of the Silver Seven had a huge impact on the growth and commercialization of hockey. Almost immediately, wealthy buyers of hockey talent went on exorbitant spending sprees in their quixotic effort to claim Stanley. Their free-for-all bidding wars weren’t simply affluent indulgence. The wild endeavours promoted their hometowns and industries. Though, as Ambrose O’Brien discovered after signing Cyclone Taylor to his Renfrew Millionaires for a reported $5,250 in 1909–10, all-star talent assured nothing, except club deficits. Taylor did however become the highest-paid team athlete on a per-game basis in North America.

For all the cup accomplished in shaping Canada’s national pastime and influencing our winter customs, the much-coveted grail wasn’t impervious to criticism. Under the weight of its celebrity in an increasingly chaotic marketplace of ringers and rich entrepreneurs, the politics of hockey’s top award jeopardized its standing. How much was public posturing is debatable, but seldom has the cup stirred greater controversy than in 1903 and 1904.

The cup’s trustees faced a barrage of disputes, as Racey depicts in April 1904’s editorial Cast Adrift. A decade of cup challenges had league organizers in Western Canada, Ontario, and Quebec seriously rethinking its merits, believing the trophy “has become more of a nuisance than a blessing.” The cup never actually belonged to any one league, and now, noted Montreal Star reports, “A scheme is under way to relegate the Stanley Cup to the realm of past history, and to inaugurate a new trophy for competition among the hockey clubs of the Dominion.”

The Star’s story, no more than brief columns buried in the sports pages, caught the eye of Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL) president Harry J. Trihey, who promptly backpedalled, admitting that the call to set the cup “adrift … has been made somewhat prematurely.” Trihey appeared to be staging a power grab. He wanted a different board of cup trustees, one appointed by the leagues “to receive all challenges, settle all disputes, decide all protests and to frame rules and regulations to govern Cup contests.”

In reality, the trustees couldn’t oblige all challenge requests. “A multiplicity of hockey leagues is a mistake,” stated trustee Philip Ross, who sought an amalgamation between the CAHL and the newly formed Federal Amateur Hockey League. Otherwise, the trustees would “continue having a hard row to hoe to please everybody, yet keep the Cup emblematic of the genuine championship of hockey.”

Ross was right. Numerous leagues complicated matters. Yet he continued to schedule cup challenges during regular-season play. Only months earlier, a dispute arose after trustees accepted a challenge from the Winnipeg Rowing Club. The CAHL had bitterly complained that the three-game series against Ottawa, from December 30, 1903, to January 4, 1904, clashed with its January 2nd regularseason start. “The matches for the Cup have simply paralyzed the game here,” accused Montreal Victorias president Fred McRobie, who could have been addressing modern-day complaints over the stoppage of NHL play at Olympic time. “Unless the Cup matches are put on a proper system, like the footballers play,” declared McRobie, “the sooner the Cup leaves here never to come back the better.”

Hockey’s growing pains elicited more cup squabbles. The Star called Stanley “Hockey Trouble,” citing unresolved issues over money, violence, and playing schedules. During February 1903’s cup challenge against Winnipeg, Montreal AAA captain Dickie Boon threatened to return the cup to the trustees based on “the way we have been compelled to play, and the chances we have been compelled to take in the middle of the season of seeing our best men knocked out of business.” Boon furthered, “Mr. Ross has not administered his trust rightly, and anyhow the Cup is far from beneficial to the game; it is detrimental to it.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Referee Percy Quinn heaped on additional criticism. After that 1903 best-of-three series was extended to a fourth game (to settle the 2–2 overtime in Game 2), Quinn announced his retirement because “three matches are a sufficient number to officiate at” in cup challenges. True to his word, Quinn quit, and Ottawa’s Chauncey Kirby replaced him. Boon finished the series, captaining the AAA’s 4–1 Stanley Cup victory. He played another two years, without winning again.

The Stanley Cup survived, of course. It may have lost some lustre in all the drama and looked somewhat shopworn from its numerous challenges and subsequent celebrations. But it was still a good friend, even to its fault-finders. Moreover, the cup had grown increasingly important to Canadians. Keeping it seemed like the right and smart thing to do.

By now the Stanley Cup’s simple bowl shape — and, later, its barrel bottom — was becoming the most visible legacy of professional hockey and an exemplar of sporting play. In 1907, A. Anglin sketched the cup being held aloft in his modest masterpiece Say Uncle! Kenora, Ontario, had reached dizzying heights as the outliers of hockey, forever recognized as the smallest town to win the trophy. ...

Lord Stanley’s bowl had never officially been outside Canada’s borders. Then, in March 1917, the Seattle Metropolitans won the Cup. As Canadian fans can painfully appreciate today, Stanley was now residing in America, albeit as a first-time guest. For U.S. organizers, it wasn’t for lack of trying. A decade earlier, in January 1907, A.S. McSwigan, manager of the Pittsburgh Pro HC, called for a Stanley Cup challenge. The Pittsburgh Press hyped: “This would cause more interest in hockey than anything that has ever happened in the States.”

In Seattle, the cup final attracted the greatest sports crowd in civic history. The local press produced several photo illustrations and described the contest against Montreal as the first “world series ever fought on American ice.” Seattle’s Post-Intelligencer giddily wrote, “Seattle is hockey wild today,” and it dubbed the rival Canadiens the “French Wizards.” Fans across the northwest and as far as Alaska and Los Angeles packed Seattle’s arena. Dozens of reporters covered the series, three from Vancouver alone. Both telegraph companies in Washington State installed special wires at the arena to bring the games to distant places.

Interestingly, Stanley’s stateside residency brought little negative commentary. Most observers saw the news as an East-West hockey issue, rather than as a Canada-U.S. concern — or as a one-off, and not worth getting into a national froth over. One Toronto Daily Star editorial called the Mets’ victory “a good thing,” suggesting it remain in America because after the trophy had “drifted into the professional ranks … possession of the Stanley Cup has meant little or nothing.” This was just more bellyaching by Toronto’s press, still faithfully touting the superiority of amateur play. Cartoonists were no more inclined to tackle the issue, sketching little of the cup’s historic departure in 1917. Nobody was drawn and quartered in major newspapers — not the players, not the cup trustees, and not the Quebec-born Patrick brothers, who owned the Pacific Coast Hockey Association’s Seattle franchise and had raided the Toronto Blueshirts of five regulars for their Stanley Cupwinning Metropolitans.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement