The Roots of Inequality

The reserve of Waywayseecappo was created along the Birdtail River of what is now western Manitoba in 1877 — ten years after Canadian Confederation, three years after the signing of Treaty 4, and one year after Parliament passed the first version of the Indian Act. The community of Rossburn was begun by European settlers only two years later on the other side of the same river.

As the town and surrounding lands were populated by settlers, the movements of the Indigenous inhabitants became ever more restricted, and their very livelihood from hunting and fishing was threatened. But that was only the beginnings of a divergence in the fortunes of the neighbouring communities that in many ways mirrors the differences between the lives of Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians.

The authors of a new book say “there is nothing accidental or inevitable about poverty in Indigenous communities.” In Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation, Andrew Stobo Sniderman and Douglas Sanderson (Amo Binashi) trace the historical and continuing reasons why the prospects and outcomes for young people growing up in the two adjacent communities have been and remain so different.

Sanderson is the Prichard Wilson Chair in Law and Public Policy at the University of Toronto and is Swampy Cree, Beaver clan, of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation near The Pas, Manitoba. Sniderman is a writer, lawyer, and Rhodes Scholar from Montreal, as well as a former law student of Sanderson.

Sniderman and Sanderson say they wrote the book not only to demonstrate historical injustices revealed by their extensive research but also to “imagine a better future” where “Indigenous children and their communities are given a fair chance” to live as equals alongside non-Indigenous Canadians. They note their efforts to use terminology such as “Indian,” “Native,” or “Indigenous” as appropriate to particular contexts.

‘Let Us Live Here Like Brothers’

by Andrew Stobo Sniderman and Douglas Sanderson (Amo Binashi)

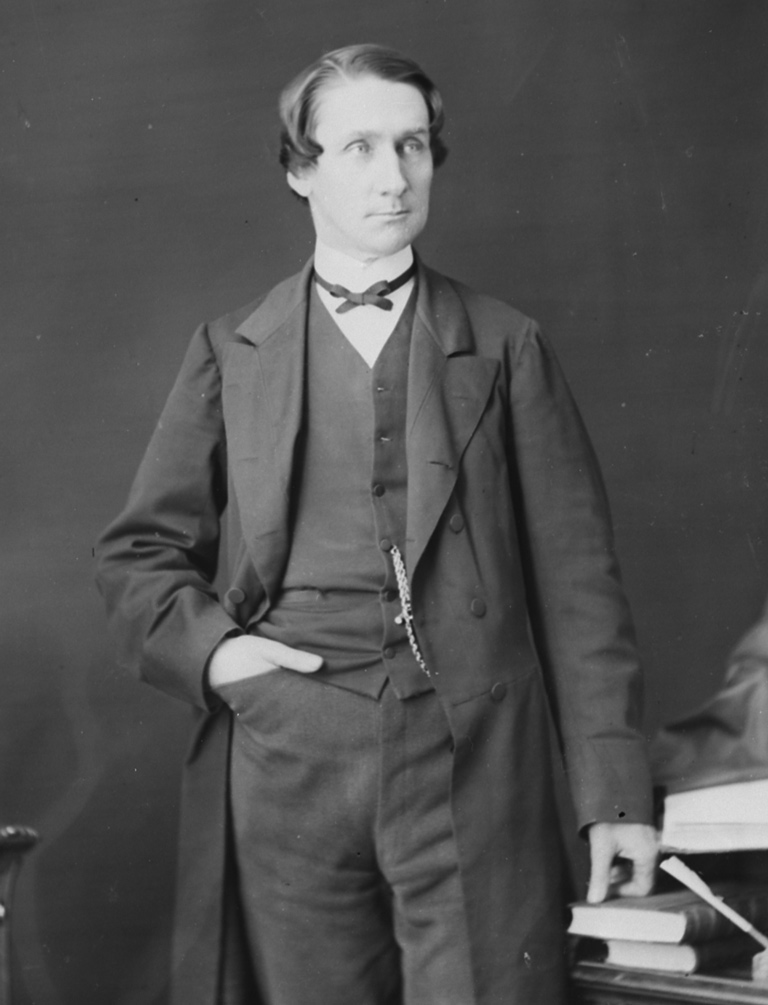

“What I have to talk about concerns you, your children, and their children, who are yet unborn,” the treaty negotiator Alexander Morris said to hundreds of Cree and Ojibway Indians gathered inside a cavernous tent three hundred kilometres northwest of Winnipeg. “What I want is for you to take the Queen’s hand, through mine, and shake hands with her forever.”

The year was 1874, and Canada was seven years old. Politicians in faraway Ottawa dreamed of a railway stretching from the east coast to the Pacific Ocean bearing goods and settlers. With this spine of iron, Canada could stand up to the United States. But a major obstacle was blocking this grand plan: Indigenous Peoples claimed to own the land over which these trains would run. So the government sent Morris, a lawyer and politician with a gift for metaphor, to make a series of deals.

Morris arrived with two armed battalions dressed in Her Majesty’s signature redcoats —113 men in all, along with a two-hundred-pound cannon. Indians made up the majority in the prairies, and Morris estimated that they could field as many as five thousand warriors for battle, if it came to that. But he did not want a fight. The federal government had neither the will nor the means to conquer the West with soldiers and bullets. Ottawa preferred to avoid the kind of bloody, drawn-out “Indian wars” that were then roiling the American Midwest. Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie instructed Morris that “our true policy was to make friends of [the Indians] even at a considerable cost.”

At these treaty talks in the fall of 1874, Morris was charged with securing control of 120,000 square kilometres without firing a shot. Negotiations began on September 8, just as the landscape was darkening from green to brown following the first overnight frosts. The soldiers accompanying Morris had erected a marquee tent on the shore of Lac Qu’Appelle — the “Calling Lake,” named for its echoes. At dawn, a layer of mist covered the water, but the white veil lifted as the sun climbed. Morris dispatched a bugler to announce the start of the first meeting. The blasts from the brass horn rolled across the water.

Like other statesmen of his day, Alexander Morris was an unabashed imperialist. He hoped “Christianity and civilization” would replace “heathenism and paganism among the Indian tribes.” Yet he did recognize what he called the “natural title of the Indians to the lands,” as had Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, who characterized Indians as “the original owners of the soil.” Morris’s job was to settle their claims.

The year before, in 1873, Morris had received a letter from a group of Chiefs in the prairies who had spotted white surveyors marking off land. The Chiefs wished to “inform your Honor that we have never been a party to any Treaty ... made to extinguish our title to Land which we claim as ours ... and therefore can not understand why this land should be surveyed.” One of the Chiefs was identified as Wahwashecaboo, an early spelling of Waywayseecappo.

Cree and Ojibway negotiators knew their long-standing ties to the land and ongoing presence gave them some leverage, but they also understood that their bargaining position had been deteriorating. Recent smallpox epidemics in the prairies had subjected each Native life to a coin toss: one in two died. And the buffalo that had provided them with food, clothing, and shelter were depleted, owing in part to a concerted American campaign to slaughter the herds. (“Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone,” a U.S. Army colonel once boasted.) Indians on the prairies were in acute need of new livelihoods.

They also sensed that trickles of white settlers augured a flood. As one Cree leader put it, Indians could not “stop the power of the white man from spreading over the land like the grasshoppers that cloud the sky and then fall to consume every blade of grass and every leaf on the trees in their path.”

Another threat lay to the south: American traders who crossed the border were showing no qualms about killing Indians who got in their way. Morris referred to these incidents as the “constant eruptions of American desperadoes.” During one incursion of heavily armed traders across the Canadian border in the summer of 1873, more than twenty Indians were killed in what came to be known as the Cypress Hills Massacre. And the cavalry of the United States Army was feared even more — Indians referred to them as the “long knives.” For the Cree and Ojibway Indians who gathered at Lac Qu’Appelle, a deal with the Queen’s redcoats seemed like a safer bet than the alternatives.

Morris, a seasoned negotiator, knew which strings to pluck. “We are here to talk with you about the land,” he said to those gathered in the marquee tent. “The Queen knows that you are poor. ... She knows that the winters are cold, and your children are often hungry. She has always cared for her red children as much as for her white. Out of her generous heart and liberal hand she wants to do something for you, so that when the buffalo get scarcer, and they are scarce enough now, you may be able to do something for yourselves.”

In response, two Cree Chiefs, Kakushiway and Kawacatoose, sought to unnerve Morris. They arranged for bags full of soil to be carried into the tent and laid at Morris’s feet. Kawacatoose asked Morris how much money he had brought, because for each sack of dirt Morris would need a full sack of money. Then Kawacatoose said, “This country is not for sale.”

One of the main Ojibway spokespeople was Otakaonan (translated to English as “The Gambler”). He belonged to the band led by Chief Waywayseecappo, who had not himself travelled to Lac Qu’Appelle for reasons lost to history.

Speaking through a translator, Otakaonan opened by recalling how his people had welcomed European settlers to the plains. “When the white skin comes here from far away I love him all the same,” he said to Morris. Yet Otakaonan objected to the way the government had recognized land rights claimed by the Hudson’s Bay Company, a British trading group that had been operating in the area. Four years before, in 1870, the federal government had paid £300,000 to the company to purchase these supposed land rights. Otakaonan did not think the Hudson’s Bay Company should have been paid for territory it did not rightfully own.

“When one Indian takes anything from another we call it stealing,” Otakaonan said.

“What did the Company steal from you?” Morris asked.

“The earth, trees, grass, stones, all that which I see with my eyes.”

Morris was unmoved. “Who made the earth, the grass, the stone and the wood?” he asked. “The Great Spirit. He made them for all his children to use, and it is not stealing to use the gift of the Great Spirit.” Morris pointed out that the Ojibway had themselves arrived on the prairies only a few generations before, after migrating west from the Great Lakes region in the eighteenth century. (Morris left unspoken the fact that aggressive Euro-Canadian settlement was a cause of the Ojibway migration.) “We won’t say [the Ojibway] stole the land and the stones and the trees,” Morris continued. “No ... the land is wide ... it is big enough for us both, let us live here like brothers.”

This sentiment met with approval from an Indian named Pahtahkaywenin, who agreed on the need for co-operation: “God gives us land in different places and when we meet together as friends, we ask from each other and do not quarrel as we do so.” To reach a deal, Morris offered one-time cash gifts, annual payments, and hunting rights on land that remained unsettled. He promised 640 acres for every family of five on “reserves,” land that would be protected from encroachment by settlers. The government would also provide agricultural assistance so that, in time, farms on reserves would provide the livelihood that buffalo no longer could. And the government pledged to build schools on the reserves and send teachers, so that Indians might “learn the cunning of the white man.”

“We won’t deceive you with smooth words,” Morris insisted. “We have no object but your good at heart.”

“Is it true you are bringing the Queen’s kindness?” a Chief asked.

“Yes, to those who are here and those who are absent,” Morris replied.

“Is it true that my child will not be troubled for what you are bringing him?”

“The Queen’s power will be around him.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

After six days of negotiations, a document titled “Treaty No. 4” was finalized on September 17, 1874. Morris had likely arrived at Lac Qu’Appelle with a pre-drafted template that left only a few blank spaces for dates, names, territorial limits, and payment amounts. The final text of Treaty 4 was virtually indistinguishable from another treaty Morris had negotiated the year before (“Treaty No. 3”), which applied to another massive expanse of territory in Ontario and Manitoba. Morris would ultimately negotiate four similar treaties dealing with land between the

Great Lakes and the Rocky Mountains.

It is highly doubtful that government and Indian negotiators shared the same understanding of what Treaty 4 meant. The text was written in English, which the Indian negotiators could not read. When Morris instructed a translator to read the document out loud before the parties formally signed, a white observer found it “immensely amusing” to watch the translator’s “look of dismay and consternation” as he attempted to hold the “bulky-looking document” and convert the English into Cree and Ojibway.

According to oral history, the Chiefs believed that the treaty represented a partnership that bonded Indians and settlers into one family, with a commitment to share the land and bring mutual aid. The government would take a more narrow view, relying heavily on the legalese affirming, among other things, that with their signatures the Chiefs agreed to “cede, release, surrender and yield up ... all their rights, titles and privileges whatsoever, to the lands.” (This provision became known as the “surrender clause.”) Morris would later describe the terms of the treaty as “fair and just.” One hundred years later, a group of Indigenous leaders in Manitoba would describe Treaty 4, and other treaties like it, as “one of the outstanding swindles of all time.”

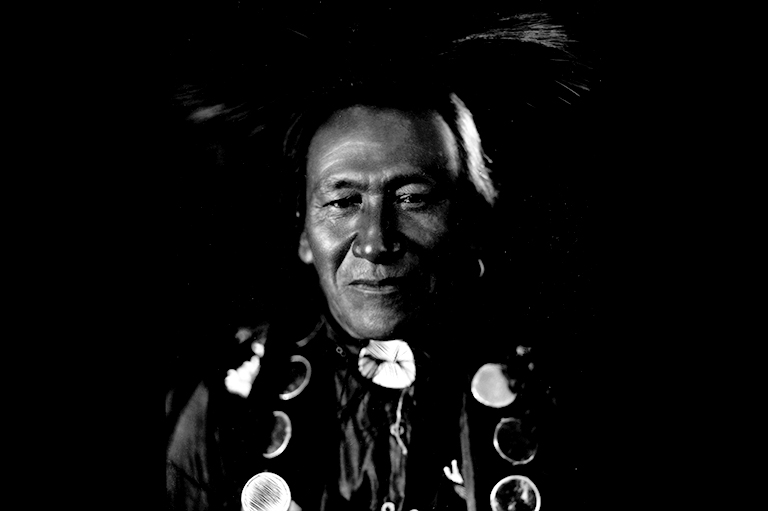

After a signing ceremony, Morris travelled two hundred kilometres east to Fort Ellice, where he was to meet with more Indian leaders who had not been present at the Lac Qu’Appelle negotiations. Among them was Chief Waywayseecappo, who was then around fifty years old.

At least as far back as 1859, Waywayseecappo had been trading furs at the Hudson’s Bay Company outpost in Fort Ellice, in exchange for cloth, flints, knives, tobacco, and ammunition. A company trader described Waywayseecappo as “a giant in size and ancient in days and devilment.” Morris wanted Waywayseecappo to sign Treaty 4 on behalf of the fifty families in his band, which Otakaonan had not had the authority to do at Lac Qu’Appelle. “What we offer will be for your good,” said Morris. “I think you are not wiser than your brothers.”

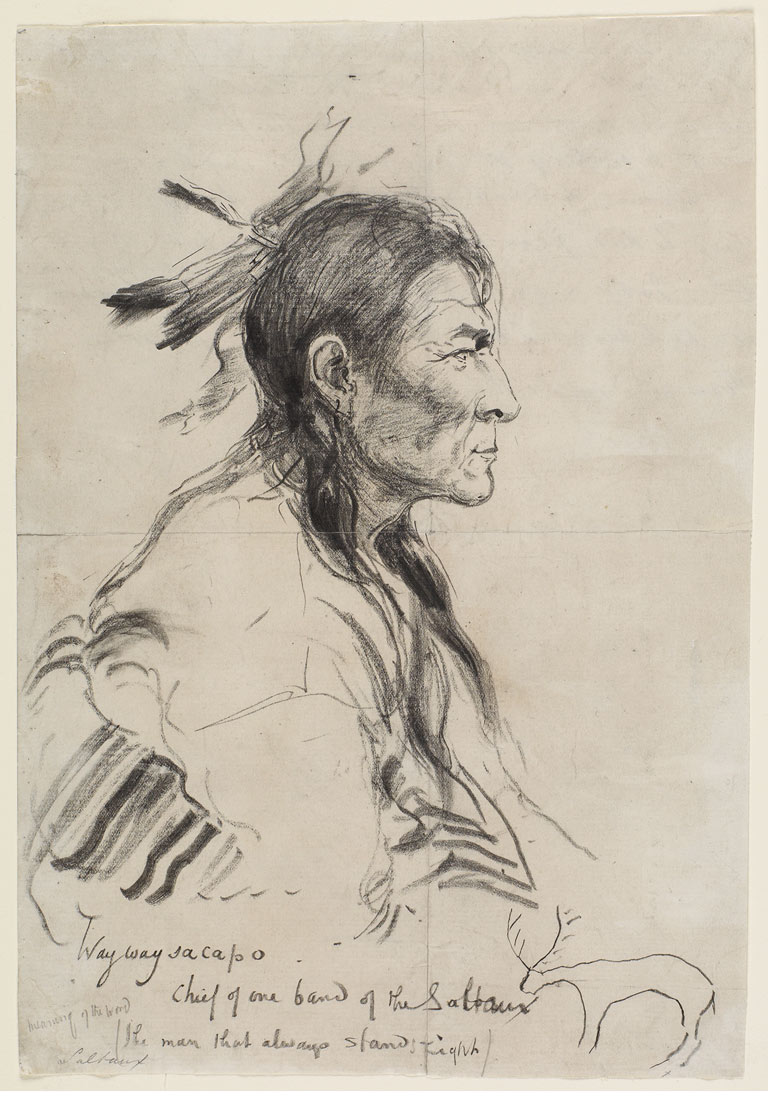

A witness to the meeting sketched Waywayseecappo’s profile with a lump of charcoal, leaving his only surviving likeness.

Chief Waywayseecappo, who could not read or write English, signed the treaty with an “X.” His name, transcribed as “Waywa- se-ca-pow,” was translated as “the Man proud of standing upright.” It is difficult to say what Chief Waywayseecappo thought about the treaty….

The Waywayseecappo reserve and the town of Rossburn were created within two years of each other, and not by coincidence.

After signing Treaty 4, Chief Waywayseecappo requested reserve land in an area where his band had planted its summer gardens since the early 1800s, inside a far larger Traditional Territory where they had lived, hunted, and traded for the previous century. The reserve was formally established in 1877, and some two hundred people moved there. Among them were families named Longclaws, Keewaytincappo, and Jandrew — names that later featured in some of the thickest branches of Maureen Twovoice’s family tree. For a time, the government referred to the community as Lizard Point, a name inspired by the dark green salamanders that were ubiquitous in the area after extended periods of rain. An early map of the reserve — formally known as Indian Reserve #62 — shows that it is bordered on the east by the Birdtail River.

Treaty 4 simultaneously authorized the creation of reserves and declared “that it is the desire of Her Majesty to open up [land] for settlement, immigration, trade and such other purposes.” And so it was that a mere two years after the Waywayseecappo reserve was established, a wave of settlers made their way to the valley of the Birdtail, just as Her Majesty Queen Victoria had supposedly desired. …

Early relations between the new town and the reserve appear to have been largely friendly. Indians from Waywayseecappo visited Rossburn to trade moccasins, baskets, and rugs. They also sold tanned moosehides, dried elk meat, and fish from the largest lake on the reserve. Some settlers in Rossburn were given Ojibway names: one elderly man was called Wapawayap—“white eyebrow.” … According to an 1882 report by a federal official, “These Indians are all very well disposed towards the settlers, and whenever trouble has arisen it has, on all occasions which I have investigated, been directly attributable to the settlers, who dislike to see the Indians in possession of desirable locations.”

Chief Waywayseecappo himself developed friendships in town. …

It is possible to imagine how the relationship between Waywayseecappo and Rossburn might have deepened over time, built on respect, trade, and friendship. But that is not how things turned out — not at this time, not in Canada. …

One particular incident seems to capture a shift in the relationship between the two communities. In 1884, two settlers built a stone grist mill with a water wheel along the Birdtail River. The purpose of the mill was to produce flour, but one of its effects was to block fish from making their way up the river to the reserve. That year, Waywayseecappo’s residents “complained of starvation” to a federal official, in part because of the effect of the mill on their access to fish. At the time, the federal Indian agent responsible for the area was Lawrence Herchmer, who showed little sympathy. Rather, Herchmer believed hunger would motivate more industrious farming, which he saw as a necessary step in the civilizing of Indians. “A little starvation will do them good,” he wrote.

Just as families in Waywayseecappo struggled with an abrupt and painful transition from traditional livelihoods, so did many other communities that had been abruptly transplanted to reserves. To make matters worse, aberrant weather caused widespread crop failures in 1883 and 1884. Across the prairies, the overwhelming majority of Indians were depending on government food rations of bacon and flour to survive. It was called “the Time of the Great Hunger.”

In the summer of 1884, within a decade of Alexander Morris’s grand pronouncement during treaty negotiations, a group of two thousand Cree Indians assembled near Duck Lake (in present-day Saskatchewan). They discussed fears of being “cheated” by a government that had made “sweet promises” in order to “get their country from them.” They claimed that the government had not been living up to its treaty commitments, including the promises of agricultural support and supplies, and they said that Indians had been “reduced to absolute and complete dependence upon what relief is extended to them.” They told a federal official that “it is almost too hard for them to bear the treatment received at the hands of the government,” yet they were “glad the young men have not resorted to violent measures.”

The peace did not last another year.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement