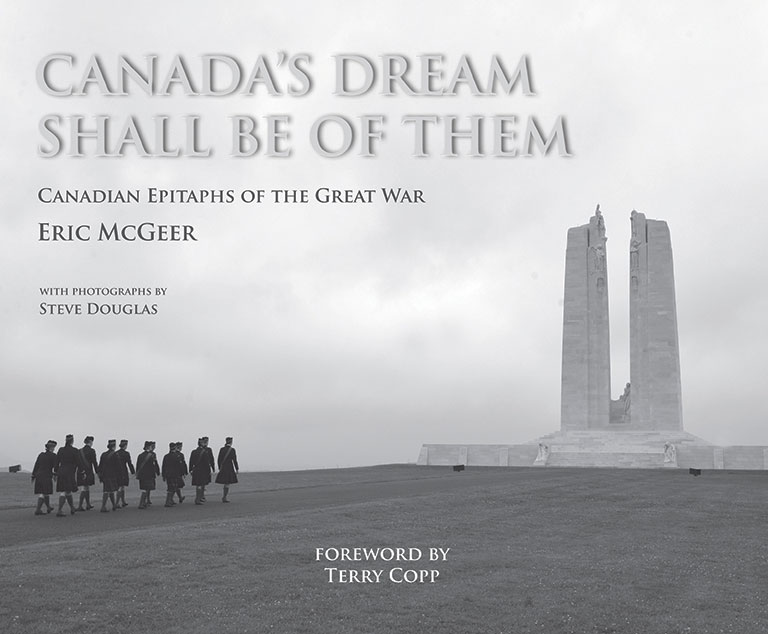

Canada's Dream Shall Be of Them

Canada's Dream Shall Be of Them: Canadians Epitaphs of the Great War

by Eric McGreer

Wilfrid Laurier University Press,

223 pages, $49.99

“Our dear daddy and our war hero. We miss you.” “J’ai fait mon devoir.” (I did my duty.) “Four years have passed and still I miss him. How I miss him none can tell. Mother.” “Killed in action. Beloved daughter of Angus & Mary Maud Macdonald, Brantford, Canada.” These moving epitaphs are but four of the thousands inscribed on headstones for Canadian soldiers and nurses who died in the First World War.

To visit the First World War cemeteries along the Western Front, or in hundreds of other locations around the world, is to feel the grief of silenced and shattered dreams. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) cemeteries, with their Crosses of Sacrifice set in tranquil landscapes, are the final resting place of Canada’s (and of what was once the British Empire’s) fallen. They number 1.7 million men and women of the Commonwealth forces for the two world wars, including some 66,000 Canadians.

The white Portland headstones mark the young and the middle-aged who never returned to their homes by providing, when possible, their name, rank, age, date of death, and unit. Canada’s silent army rests there for eternity.

Along the bottom of many of the headstones run epitaphs from grieving families. The next of kin were given sixty-six characters, including spaces, to find words to capture the haunting loss of a son, brother, father, uncle, or daughter. How does one sum up a life in a space that is less than half the length of a typical Twitter message?

In the beautifully produced Canada’s Dream Shall Be of Them, Eric McGeer’s story of Canada’s First World War epitaphs is accompanied by haunting photographs by Steve Douglas and colour reproductions of war art from the Canadian War Museum collection. McGeer offers a brief history of the war, its battles, and the CWGC, but it is the epitaphs themselves that convey the power of mourning widows, parents, and orphans who struggled to make sense of a life taken too soon.

Many of the next of kin drew solace in scripture. Others found the words of poets Rudyard Kipling or John McCrae more apt for giving expression to grief. Epitaphs appear in English, French, Latin, Danish, Welsh, Ukrainian, and other languages, too, reflecting the diversity of the Canadian Expeditionary Force that was 620,000 members strong.

Many epitaphs seem to accept the loss, as the survivors found strength in words of sacrifice regarding what many believed was a just war. But one wonders about the parents of nineteen-year-old Private Ernest Insley, killed on April 9, 1917, the first day of the Battle of Vimy Ridge: “Gone. One of the best. No words can bring him back.”

Next of kin were given twenty-six characters, including spaces, to find words to capture the haunting loss of a son, brother, father, uncle, or daughter – less than half the length of a Twitter message.

The CWGC was accommodating of the grief but refused overly angry or bitter wording. Nonetheless, it rarely censored chosen wordings. There is a moving epitaph for one British soldier who had been executed for desertion: “Shot at dawn. One of the first to enlist. A worthy son of his father.”

The epitaphs are agony rendered in stone. The family of seventeen-year-old Private Bruce Nickerson, of Clark’s Harbour, Nova Scotia, left this message: “We loved him well. Memory gives pride and sorrow.” One hundred years on, that pride and that sorrow continue to emanate from the gravestones.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement