What You Can't See

The Pas, Manitoba, 2012

Liam’s mother wasn’t making much sense. As she flicked her thumb, the images on her phone rolled up and away. “What! No way! That’s just… As if! Oooo — I’d love to just — ”

Liam made a sorry-about-that face at his friend Oliver on the other side of the chess board. Finally, he couldn’t take it anymore. “You know we can hear you, right?”

His mum looked up, bewildered. A flush of pink crept over her cheeks as she jammed the phone in her back pocket. “I’m going to make tea. Do you want some?”

Liam grinned. “You’re always telling us we need to spend less time looking at screens.”

His mother shrugged, embarrassed. “I know. It’s just . . . sometimes I see these pictures my friends post and . . . it’s weird. They tell me they’re worried about money, but their social media is all about fancy trips and new cars.”

She wasn’t really paying attention to the boys anymore. “I mean, some of them — I know how unhappy they are, but then they post these photos where everyone’s smiling, and I don’t know what to believe.”

Oliver was nodding his head. “I know what you mean. My nôhkom had to go to residential school. She always says not to believe the pictures.”

“I didn’t know your grandma was at Guy Hill,” Liam’s mum said, her face serious now.

“She says the kids in the photos would get hit if they didn’t look happy for the photographer. We only have one picture of her when she was a girl. Her hair and her dress are like all the other girls. She says she was really sad and homesick inside, but in the picture, she’s smiling.”

The corners of his mouth turned down a little. “Well, her mouth is smiling. Her eyes aren’t.”

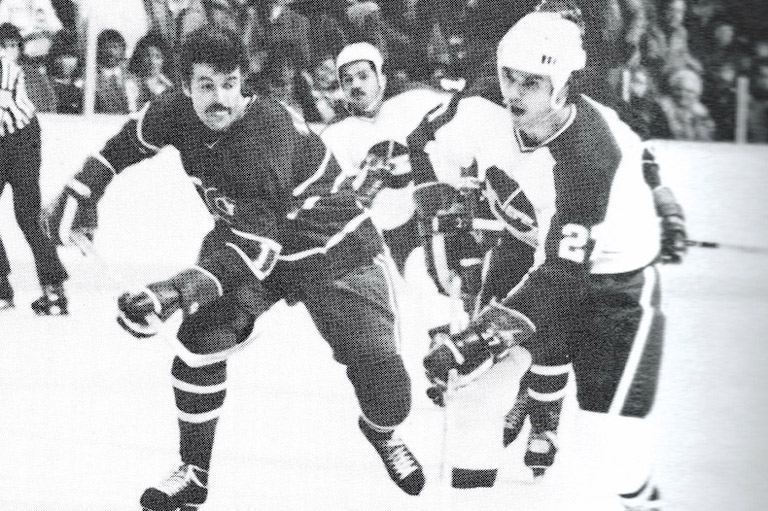

Now that he’d started, he wanted to keep talking. “My uncles played hockey on the school team. They have this great photo of them in red and white shirts before a game. They said it was the only good thing about being there. Hockey helped them forget how unhappy they were.”

Just then Liam’s dad wandered in, holding a big book. “Who’s winning?” Without waiting for an answer, he said, “Did I ever tell you about going to the provincial chess championships when I was 12?”

“About a million times!” Liam said teasingly, but his dad was lost in memories.

“I came in second in my age group. Beat some kid from Winnipeg who thought I was just this hick from up north. I was thrilled.” He poured himself a cup of tea. “But you’d never know it from the picture that went in the newspaper. I looked like I was about to cry. Everybody thought I was sad because I didn’t win. But the truth is . . .” he paused for effect, looking at the boys. “I really had to go to the bathroom!”

Liam glared at his dad, but Oliver burst out laughing. Trying to change the subject, Liam said, “I guess you never really know what’s going on in a photo. What you can’t see.”

His dad held up his book. “You know what I just learned? Some photographers at the start of the First World War needed good pictures, but they couldn’t get what they wanted. So they took photos of soldiers who were training, maybe added a few things and cropped the picture so you couldn’t see that it was nowhere near the battlefield. They weren’t trying to trick anybody — they got the real deal eventually.”

“Now that we’re talking about old photos . . . ” Liam’s mum pulled a big book off the shelf. Curious, the boys crowded around her to see the heavy pages full of photos. Grinning back at them was a much younger version of Liam’s dad. His hair curled in every direction down almost to his shoulders, and he was standing in front of a cherry-red car. “You kept refusing to get a decent haircut,” she smiled.

Pretending to be offended, Liam’s dad said, “I was planning to be a rock star!”

“I think you look great, Dad!” said Liam.

Oliver chimed in. “And that car is so cool!”

“Not if you had to actually ride in it,” Liam’s mum snorted. “It broke down right after I took this photo. Cost us a fortune to fix, and then it died completely a month later.”

She turned a page. Her face went still as she stared at a picture of a woman and two kids in matching sweaters and toothy smiles. “Is that you and Uncle Al?” Liam asked.

His mum didn’t seem to hear him at first. “He was having a tough time then. The kids were bullying him at school, but Grandma didn’t know, and he wouldn’t let me say anything. I wish I could have helped him.”

Liam’s dad put his arm around her shoulders. “We should go visit him and Paul one of these days. We haven’t been to Montreal in ages.”

She smiled and turned the page. “Oh, now here’s a nice one!”

“Mum! No!” Liam yelled. There for everyone to see was a baby who looked a whole lot like him peering over the edge of a bathtub, soapy bubbles everywhere.

Like the good friend he was, Oliver pretended to be studying the chess board. “Get ready to take a photo where you look really sad,” he said, “because I’m about to win.”

You never really know what people in a photo are thinking or feeling.

For instance, many pictures from residential schools show First Nations, Métis or Inuit kids smiling and playing. But it’s important to remember they were away from their families, living in unfamiliar buildings and eating strange food. They had to have a lot of strength to get through it. Guy Hill Residential School was a real place, and it did have a hockey program.

And yes, there are some famous fakes among the photos of the First World War, although there are far more images where photographers captured the all-tooreal horrors of battle. If your family has some photo albums, ask someone older to tell you the story behind what you see in the picture.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

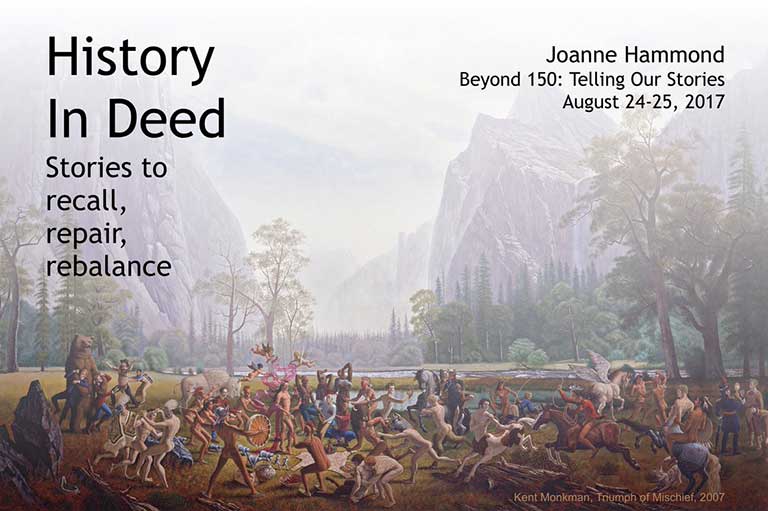

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive features both English and French versions of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids — 3 digital issues per year for as low as $13.99. Tariff-exempt!