The Canadians Who Shaped Hollywood

New York, 1909.

The creative and hungry from all over the U.S., Canada, and beyond converged upon the city like bees to a honey jar. It had been only fourteen years since the first paying cinema audience had gazed in horror at the image of a full-size train hurtling towards them.

The thrill of that Lumiere brothers presentation in Paris had sent ripples all around the world. In North America, New York was the first major centre of production.

Public thirst for this magnificent new style of entertainment with its lifelike murders, magic tricks, and amazing stunts needed constant sating. New films were needed — and needed fast. No entertainment media before or since has had quite the lure as moving pictures in this period.

Anyone with a driving hunger to “make it” could stand a realistic chance of at least some kind of work in the industry. Crowd scenes, involving hundreds of extras, were common.

There were no ready-made qualifications for standing in front of a camera. Film actors and actresses had yet to be recognized in the same way as stage performers. And classically trained actors and actresses were suspicious of this new medium, which allowed for only ten-minute storylines and no dialogue.

Film actors were rarely even billed. The last thing producers wanted was a “star” who would demand a greater salary to match their drawing power.

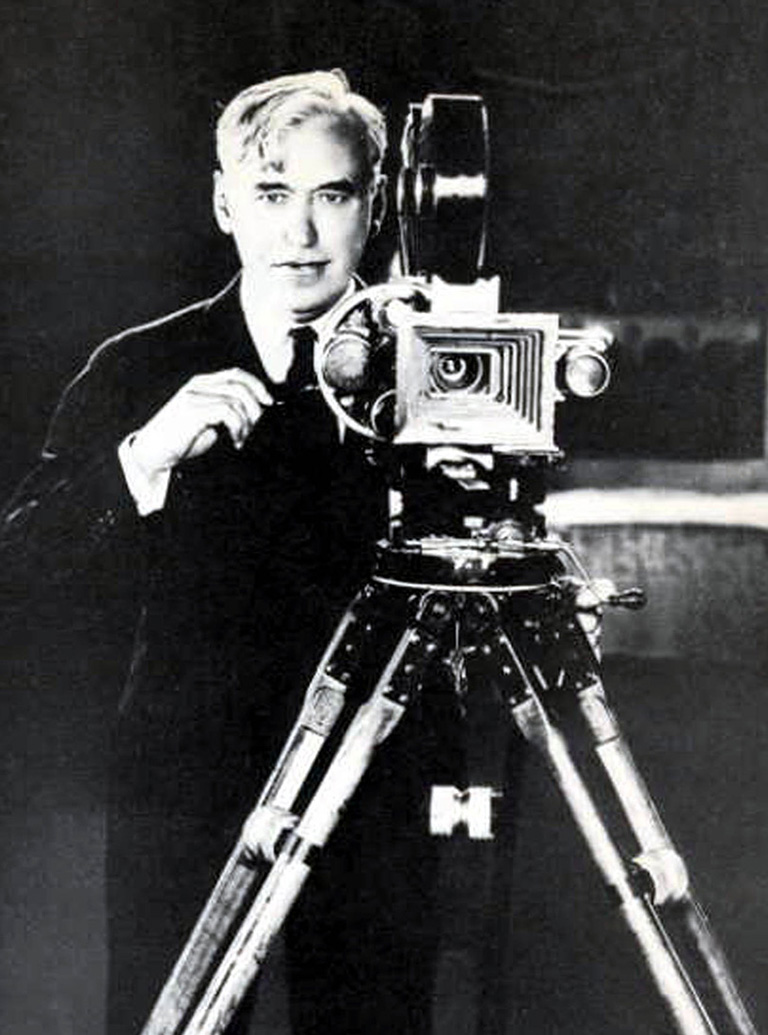

Qualities that made a good director, producer, or even camera operator had also yet to be defined. And no one was too squeamish about who did what. An actor was free to direct or write. And many writers and directors started as actors.

Into this egalitarian world came two Canadians of working-class origins who would permanently etch their influence onto the landscape of the moving picture. They were Mikall Sinnott (Mack Sennett) born in 1884 in Danville, Quebec, to Irish immigrant parents, and Gladys Smith (Mary Pickford), born in 1892 in Toronto.

Far from holding them back, humble origins were soon to propel their ambition. And an understanding of blue-collar sensibilities would also be a decisive factor helping both Canadians achieve popularity and success on a massive scale. Sennett and Pickford were both pioneers. Within a few short years, Sennett became the first major film producer who specialized in comedy. His style helped to define screen comedy in the silent era — and some would say beyond.

Pickford’s contribution was no less revolutionary. She would blow apart the idea of anonymity in screen acting, becoming the first woman who could be known, recognized, and sought after in her own right. By 1909 both Pickford and Sennett had gained entry into the world of film through the same rising star — principal director at the Biograph production company, D.W. Griffith.

Gladys Smith’s introduction to show business had come about through necessity rather than desire. Her father, a labourer, had been killed in a job-related accident when she was five years old. With little income, her mother resorted to putting her on the stage. The child toured as “Baby Gladys” so she could help feed her two younger siblings, Lottie and Jack.

Gladys made the successful transition from vaudeville to Broadway at the age of fourteen, changing her name to Mary Pickford. She was sixteen when she entered the offices at Biograph in 1909 and charmed Griffith into taking her on.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Sennett’s road to moving pictures was also uneven. When he left his native Quebec at the age of seventeen to find work in the American Iron Works in Connecticut, his only obvious show-business aspiration was to sing; his rich bass voice fueled dreams of the opera.

It was likely this dream that took him in 1902 to New York. He began to carve out a minor career in burlesque, which ultimately was to prove a major influence on his work in film.

Sennett approached Biograph a year before Pickford. He had already acted in many short films before he found himself opposite the golden-haired sixteen-year-old from Toronto in such shorts as The Gibson Goddess (1909) and The Englishmen and the Girl (1910).

By this time Griffith was already taking the whole Biograph company to California for the winter where fewer filming days were lost to bad weather. He also found an impressive range of natural landscapes — deserts, jungles, swamps, and mountains — that did not exist in the east.

While Griffith experimented with locales, two of his prodigies had ambitions of their own.

Like most actresses of her time, Pickford received no billing in her Biograph films. But as a former stage performer, she knew how to project her personality through the limitations of the medium.

Her trademark blond curls and her mixture of vulnerability and pluckiness were a cocktail audiences could not resist. Soon the public identified so strongly with the name in the intertitle of one of her films — “Little Mary” — that it stuck.

Astute and determined, the real Little Mary understood the business and her bargaining power within it. She realized that each time she moved from one company to another, she could negotiate afresh and improve on any existing contract. So Mary moved often, leaving Biograph for IMP (later to become Universal), from IMP to Majestic, back briefly to Biograph, then to the Famous Players Company.

She achieved this whole cycle in the three years between 1909 and 1912. Her weekly salary increased during the same period from $40 to $500.

Pickford soon anticipated the power of the modern film star by demanding (and getting) creative input into every aspect of the films in which she appeared. In 1916 she successfully lobbied her employer, Famous Players, for a separate production offshoot, The Mary Pickford Company, just for her movies. Three years later, together with Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Griffith, she formed United Artists.

Meanwhile, Pickford’s old Biograph colleague had also risen to prominence. Although consistently an actor in his years with Griffith (1908–1912), Mack Sennett was most drawn towards writing, directing, and producing. Constantly grilling Griffith and his technicians about every aspect of the industry, he contributed scripts for Griffith productions as early as 1909. By 1910 he was directing as well.

Sennett also focused much attention on the all-important craft of film editing. It was through this discipline that a straight scene could be made funny. Sennett soon became the master of “absurd” comedy. A typical Sennett scenario might find a small, two-door Ford coming to a hall by the curb. Out spills two, four, six, eight, twelve, twenty policemen.

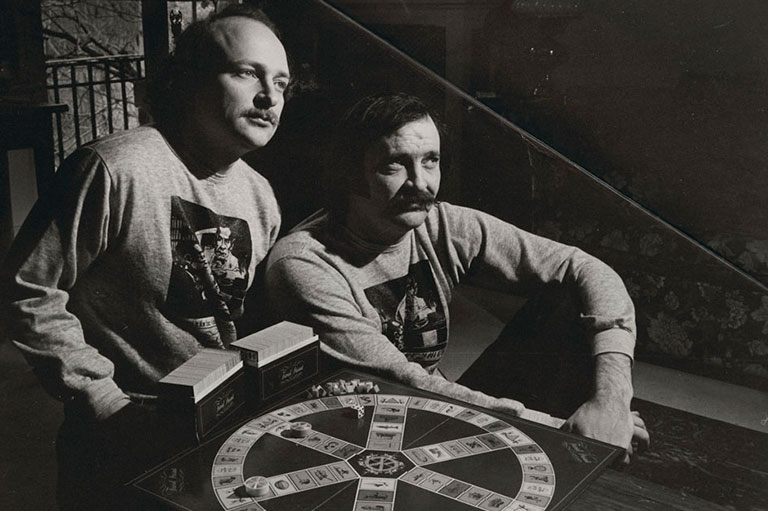

Like Pickford, Sennett wanted control of his product and in 1912 struck out on his own, forming Keystone in association with two former bookies.

He brought comedy talent from Biograph with him, notably his close friend Mabel Normand. But it was in spotting and hiring new comics that Sennett excelled. Many of the comic greats, such as Charlie Chaplin, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Harold Lloyd, and Ben Turpin, came through Keystone.

Although Sennett was influenced by the surreal comedy of French filmmaker George Melies and paid close attention to the trickery through which it was achieved, he brought in vital elements of his own. The vulgarity, the exaggerated caricatures, the lampooning of authority figures, and the sheer physical speed owed much to his own stints in burlesque and his knowledge of working-class tastes.

While his one-time mentor Griffith was drawn to vast stories with noble themes, Sennett was drawn to the anatomy of instant laughter. And often this meant parodying the “serious” films of the day. In Sennett’s first feature comedy, Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914), tiny Charlie Chaplin (before he invented his tramp character) is a city slicker preying upon an innocent farm girl played by the enormous Marie Dressier (Farm waif preyed upon by sophisticated rake was a stock melodramatic situation in “serious” films.)

Sennett inserted the incongruous or absurd into other popular storylines, casting cross-eyed Ben Turpin or Fatty Arbuckle as the dashing romantic hero.

Keystone relied on another perennial crowd-pleasing formula from burlesque — that of the rich or overly dignified being taken down a peg or two, with custard pies aimed at gentlemen in evening dress and fashionable ladies with improbable hats.

Sennett understood the ability of moving pictures to magnify laughter through scale. If one stupid cop was funny, the logic ran, a dozen would he many times funnier. And so the Keystone Kops were born.

If numbers magnified comedy, speed intensified it. A car chase through the streets was funnier if the film was sped up to create abrupt, jerky motions, and if the Kop car crashed into a lamppost at a hundred miles an hour. This crazy effect was achieved by recording the action at only eight to twelve frames per second, then projecting it at sixteen to twenty.

Such innovations put Sennett improbably in the vanguard of a very serious movement in cinema art. The effect of mechanization upon the human soul would in years to come become a preoccupation of such lauded filmmakers as Fritz Lang (Metropolis, 1926) and Sennett’s former employee, Charlie Chaplin (Modern Times, 1936).

Yet from 1912 onwards, Keystone productions were already portraying the mad choreographed dance created by man and machine in the modern world. Sennett’s humans even moved like cogs or spokes spinning madly out of control. And like parts of a machine, Sennett’s humans could be shot, burned, or flung huge distances, but never hurt.

“Having found your hub idea, you build out the spokes,” said Sennett of his plot-building techniques in 1915. “Then introduce your complications that make up the funny wheel.”

The Canadian child of the industrial age who had narrowly escaped a career in the American Iron Works was bringing his own mechanized vision to his art.

If Sennett’s understanding of lowbrow comedy was a major factor in his success, so Pickford’s knowledge of pathos became a crucial tool through which she could win over her public.

As “Baby Gladys,” she had found out that a youthful combination of plucky spiritedness, innocence, and good looks was simply irresistible to a large audience. Add peril into the mixture, and the audience would feel not only enamoured of their heroine, they would feel protective of her too.

As well as “America’s Sweetheart,” Pickford was variously known as the “Cinderella of the Screen” and “the sweet young girl every man desires someday to have for himself.”

There are some striking parallels between Pickford’s Cinderella screen persona and the details of her own upbringing. A classic example is the early gothic Sparrows (1926), a film she also produced, in which Pickford is the oldest child rescuing younger children from a baby farm (orphanage).

Our heroine here is at once protector of the imperilled and hungry young children and at the same time in severe danger herself. The similarities between this and a childhood in which she had been forced into the cutthroat theatrical world to feed her younger siblings are obvious. And her ongoing real-life role of protector can be seen in her contracts, one of which (in 1917) stipulated that the studio must offer her brother Jack a lucrative contract.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Movies like Sparrows hit a chord around the world because people recognized the essential pathos of poverty and the universality of the dream of being rescued.

One aspect of Mary’s success with audiences was her seemingly perpetual youth. When Mary played the spirited young waif in Sparrows, she was actually thirty-three years old. Her growing impatience with playing fifteen-year-olds would present her with the greatest test of her career and would ultimately cause her downfall.

The first challenge to Mary’s image, however, came not on the screen but in her private life. On March 28, 1920, with a fanfare of publicity, Pickford married Douglas Fairbanks, the charismatic, athletic actor seen by audiences as Mary’s male counterpart in purity and innocence.

Celebration turned to major embarrassment when the attorney general of California threatened to prosecute her for bigamy and perjury as there was suspicion Mary’s divorce from first husband Owen Moore had not been legal. Hollywood at this time was just beginning to experience its first wave of scandals, and a possible backlash threatened Mary’s career. In the event, she was exonerated. But it’s quite possible such a scare brought one question urgently into focus — was it time to shed the “Little Mary” image?

With the jazz age roaring around her, Mary made several attempts to do just that. The first of these was a film, Rosita, directed by German import Ernst Lubitsch in 1923.

Although a failure, Mary persevered. In 1929, she discarded her trademark blond curls and replaced them with the fashionable 1920s shingled hairstyle to play the title role in the film Coquette, her first talkie. Although she won an Academy Award, the audience felt cheated out of “the girl with the golden hair” and Mary’s popularity began to wane.

Pickford was by now entering her late thirties. Even if her public could not yet admit it, Little Mary’s days were numbered. Already the advent of sound had removed some of the pantomime quality from moving pictures. Naturalism was the order of the day, and it was becoming difficult to fool an audience with inappropriate casting.

Mary turned to Shakespeare in her last real attempt to carve out a new acting niche. But The Taming of the Shrew (1929), in which she starred opposite Fairbanks, was by all accounts something of a disaster, and Mary soon retired from acting.

Sound also proved to be the decisive blow to Sennett’s career. But the golden years of 1912—1915, in which he ran Keystone independently as a brisk comedy factory, were already long gone. After World War I, audiences had began to change, becoming more sophisticated in their tastes.

The German cinema with its dark shadows and psychological themes was beginning to influence the American film. The public began to expect longer stories and more serious treatments. Sennett’s films became less vulgar and more polite, and the 1920s were very profitable for him.

But he remained a fish out of water with the new middle-class style of comedy. The fragility of his product became more obvious when very few of his actors made a successful transition to talking pictures. To make matters worse, while Sennett moved upmarket, the downmarket burlesque approach was snatched by the emerging world of cartoons.

It’s easy to paint the inevitable decline of great careers in a tragic light. In fact, the reality is seldom so simple or so sad. Despite personal bankruptcy and the advent of sound, Sennett still managed to discover one more comic genius in W.C. Fields. And although he returned to Canada in the 1930s, he was often recalled to Hollywood to act in various advisory capacities until his death in 1960. Pickford also remained active in film, becoming the first vice president of United Artists in 1936.

But it is the intense excitement in that early film era that causes us to see sadness in whatever follows. And one measure of this dazzling mystique — and the inevitable disappointment that lies in its wake — is the true story of Mary Pickford buying up all her silent film originals in the 1930s solely to have them burned at her funeral. Luckily, for film archivists and the world in general, Pickford relented before her death in 1979.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.