The Best Year of His Life

“Rugged, rocky, cliffy, fretted with coves, bays, inlets, sprinkled with islands, sailboats, freighters, fishing smacks … There were half-remembered landmarks. Church steeples. The silver curve of railroad tracks. Dirt roads winding among wooden houses …”

It is 1944, and munitions instructor Sergeant Harold Russell lies in a hospital bed dreaming of North Sydney, Nova Scotia, where he was born. Just days after losing his hands in a freak accident, heavy drugs keep him in a state somewhere between sleep and delirium. Harold imagines himself floating down to touch the Nova Scotian ground, then feels himself being hoisted onto his father’s shoulders and taken to downtown Sydney where people are cheering and waving flags to celebrate the end of World War I. “Never again in your lifetime will you see a celebration like this, my boy,” Harold’s father tells him. “There will never be another war.”

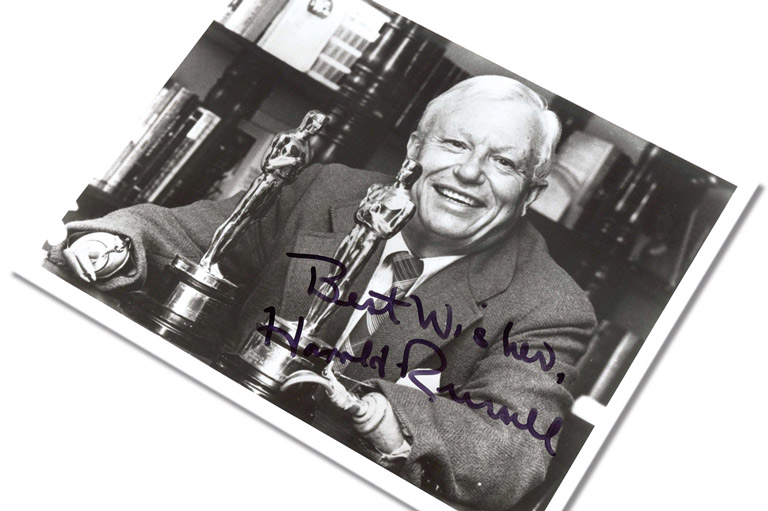

Harold Russell’s life is at an all time low. No one could possibly predict that in just a few more years, he will achieve a unique distinction in one of the world’s most competitive and prestigious professions – a profession into which he had never sought entry. At the 1946 Academy Awards, Russell will become the only actor ever to win two Oscars for the same role.

As the war drew to a close, things began changing in the world of film. Public hunger shifted away from Errol Flynn–style heroics. People wanted to see movies that reflected the disruptions and adjustments they were experiencing in their own lives. Ex-servicemen were flooding back to their American, Canadian, and European hometowns to find that civilian life had challenges of its own.

The germ of the story that would propel Russell to international fame began taking shape as early as August 1944 when MGM mogul Samuel Goldwyn read an article in Time magazine about a group of injured marines trying to readjust to civilian life. Aware that this was an emerging topic in North America, and beyond, Goldwyn commissioned MacKinlay Kantor to write a novel that would provide the basis of a screenplay.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The resulting poem in blank verse, Glory for Me, included seaman Homer Wermels, who returns home from the war drooling and suffering from body spasms. Homer symbolized the shattering effect of war. Although Harold Russell would not know until much later, he would radically change the concept of this supporting character.

Harold John Russell was born in North Sydney, Nova Scotia, in 1914. After his father died in 1919, Harold’s family moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where his mother trained to be a nurse. Intending to found a hospital in Cape Breton, she planned to return to Canada with her three sons once qualified. In the end, however, the family remained in the United States.

There was little in Harold’s early life to suggest a future as a film star. In fact, the young man viewed himself as a nonentity. “As a kid in Nova Scotia I had failed to make friends,” he recalled. He had “only barely squeaked through in school.” Harold intended to become an engineer, but had failed to obtain the necessary college scholarship. Instead, he went to work in a grocery store, progressing slowly from delivery boy to meat cutter to store manager.

The same lack of confidence affected his relationships with the opposite sex. When Rita, the girl he was timidly courting, appeared unimpressed by her suitor, Harold enlisted the help of an uncle who had connections. Despite such interventions, Harold’s inferiority complex persisted until an unlikely turning point. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941, Harold Russell immediately enlisted in the U.S. war effort.

While he had failed to realize his ambitions as a civilian, the forces soon picked Harold out for advancement. After mastering the art of parachuting and learning how to set a booby trap, Harold was asked to stay on at demolition school as an instructor. Working steadily with an increasing number of trainees, he was promoted to sergeant, but as months turned into years, a new anxiety developed. “Out of eighteen instructors [at demolition school],” he recounted, “eleven had been injured in the seven months I’d been teaching there.” The worst of these incidents involved him and another instructor who had gone up a tree to fix a charge. It exploded and blew off his fellow instructor’s hand. The experience was a bad omen. Harold resolved that if he were to be injured, it should at least be in battle rather than in a training exercise, so he sought a transfer.

Harold succeeded in getting transferred to an outfit in North Carolina that was preparing to go oversees, but there were intensive demolition exercises to get through first. It was during one of these practices that disaster struck.

There was no warning. Watched by his class as he was going through the same routine he had followed countless times before, Harold “crimped the cap and fuse, slid them in. Then – BOOM!!!”

The agonizing recovery and rehabilitation process brought many issues to the fore, the worst of which was Harold’s sudden belief that his success as a soldier had been the odd fluke that only wartime could produce. Lying in a hospital bed day after day, he began to feel that joining the army had merely provided “a glamorous alibi for running away from a job that offered little, a girl [Rita] I had failed to win.” Having vowed to himself before the accident that he would never return to his old job, it now seemed that even the options he had rejected were closed to him. At Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C., Harold went through operations on his stumps to enable the fitting of prosthetic hooks. Ever eager for a challenge, he began to practice manipulating his new hands. He wanted to become as independent as possible.

Harold’s dexterity opened up an unexpected door. The army was in the process of commissioning an instructional film to inspire amputees to overcome their disabilities. Harold’s progress with his prosthetic hooks made him the perfect subject. A film crew captured him performing various, everyday tasks – squeezing toothpaste, playing Ping- Pong, dialing a rotary telephone. Diary of a Sergeant, shot both in the Walter Reed Hospital and at the old Paramount studios in Long Island, was released in March 1945. At the premiere, Harold reacted with pained embarrassment to the sight of himself on celluloid. “I wriggled and squirmed and blushed as I watched my shadow go lumbering across the screen,” he said, “And as for acting, I winced every time that oversized gargoyle tried to portray anything more complicated than staring into space.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Although the film was narrated and he had no lines, Harold’s innocence and good-natured humility had a way of showing through. For the unwitting Harold, Diary of a Sergeant was to act as a calling card.

Meanwhile, in Hollywood, casting the Homer Wermels character – as written in MacKinlay Kantor’s poem Glory For Me – was proving a stumbling block both for Samuel Goldwyn and for William Wyler, the film’s director. Then things changed. One evening, Wyler saw a screening of Diary of a Sergeant. As the young director watched the fresh-faced Sergeant Russell cheerfully negotiate day-to-day tasks with his hooks, he was struck with an idea. He rushed to phone Goldwyn. The next morning, Goldwyn had a private viewing of the army film. When he saw Harold, he exclaimed, “Get me that man!”

Unbeknownst to Harold, who was busy attending business classes in Boston, his acting career had already taken off. A woman phoned him, claiming to represent Samuel Goldwyn, and offered Harold a role in a movie starring Fredric March and Myrna Loy. Naturally, the young veteran assumed it was a joke. The woman persisted, however, and soon a meeting with MGM was arranged in New York. Harold was offered $5,000 for the part and told to hurry his answer. Practical, yet a little naive, he ignored the concerns of his now-fiancée, Rita, about accepting too quickly. “The way I figured it then,” he later said, “Goldwyn was practically throwing his money away. I was no actor.”

Although the contract was doubled in renegotiations, Harold Russell received no residuals. Later, he regretted his cavalier attitude toward payment. In the short term, however, he was off to Hollywood, where his status as an innocent would soon reap unexpected rewards. The film – titled The Best Years of Our Lives and rewritten by playwright Robert E. Sherwood – was soon underway, and Harold enjoyed rubbing shoulders with famous co-stars and an odd assortment of film people, including the “old man” himself, Samuel Goldwyn.

But Wyler’s motto to actors, “If it feels right, do it,” was not meant for Harold. Often, he came across as too cheerful for such a troubled character. He had a problem conveying anger. In one scene, Harold’s character (renamed Homer Parrish), was supposed to react angrily to fascist comments made by a customer at a soda bar, throwing the loose-lipped customer through a glass counter. However, Harold liked Ray Teal, the actor playing the fascist, so he was unable to express the necessary rage.

Thinking about how he could rile the ever-placid Harold, Wyler took him aside and “confided” that, despite appearances, Teal really was a fascist, and there was literature in his pocket to prove it. The gullible young veteran believed Wyler, displaying newfound enthusiasm in his onscreen outburst.

The low-key authenticity of Harold’s performance was part of a deliberate plan. Wyler was looking for a subtle, naturalistic sensibility not typical of Hollywood films. Adding to the texture of naturalism, actresses Myrna Loy, Teresa Wright, and Cathy O’Donnell were asked to refrain from wearing makeup and to wear their costumes a few weeks in advance of shooting, so they would feel more comfortable in their roles.

The lives of three returning servicemen were depicted in a similarly plain and honest fashion. Homer (Harold Russell), from the navy; Al (Fredric March), from the army; and Fred (Dana Andrews), from the air force, return to their hometown together. Flying home on the same plane, they share war stories, admitting to one another their dread and uncertainty of going home. Using his hooks, Homer can light his own cigarettes and carry his bags but, as his two new comrades reflect, the navy could not teach him how to take his girl in his arms.

Later, in a touching scene that paralleled Harold’s relationship with Rita, Homer’s childhood sweetheart, Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell), makes a final attempt to get through to her recently disabled friend (and former fiancé). Bitter and afraid of rejection, Homer’s best defense is to reject first. Eventually he relents, allowing Wilma to help him unfasten his prosthetics and get into bed. Ironically, accepting her help is yet another effort to drive her away. Homer reasons that by assisting him, Wilma will discover for herself the unromantic truth of his disability.

When The Best Years of Our Lives was released in 1946, audiences in North America and Europe immediately identified with the disillusioned vets and also recognized the suffering of those who had been left behind, represented by such characters as Wilma. Many women on the home front confronted the horrors of war in a different way – by dealing with the psychological scars of their returning men.

Many scenes, even some not involving Homer, mirrored aspects of Harold’s own rehabilitation. Fred fears returning to the menial work he escaped from to become a flying ace in the air force. This dilemma Harold knew only too well. Without a great deal of luck, career opportunities and personal fulfillment were elusive for the returning vet.

The most striking parallel of all, however, is the film’s last scene in which Homer marries Wilma. Harold did indeed marry his childhood sweetheart, Rita, in Hollywood while The Best Years of Our Lives was still shooting. And, just as in the film, he had struggled to believe he was a suitable mate after his injury.

Although both critical and public response to The Best Years of Our Lives was highly favourable, the film was not without its detractors. Abraham Polonsky, writing in the Hollywood Quarterly, believed that the film too neatly resolved the characters’ displacement in society by its happy ending. But at the Oscars that year, The Best Years of Our Lives cleaned up, winning best director, best script, best music, best film editing, and best actor (Fredric March), eclipsing Frank Capra’s perennial Christmas favourite It’s a Wonderful Life, which was also nominated in many of the same categories.

Harold Russell won a special Oscar for “being an inspiration to all returning veterans.” Although also nominated for best actor in a supporting role, he was not expected to win. “I found out, months later,” he recalled, “that when I was nominated for supporting actor, they figured I didn’t have a chance; the other guys [Charles Coburn, William Demarest, Claude Rains, Clifton Webb] had too much background.”

When they did announce Harold’s name for the award, he was as unprepared as everyone else. “When they got to supporting actor, they practically threw me out on the stage.” While the modest Harold took the new level of attention cheerfully in stride, some professional actors, such as fellow nominee Clifton Webb, did not appreciate being upstaged by a novice. “On Razor’s Edge,” he later said, “I lost the supporting actor Oscar to that man with no hands. It caused a scandal.”

Following advice from Wyler, and his own common sense, Harold made little attempt to duplicate his initial Hollywood success. Instead, he continued his education at business school and set up a consulting firm, Harold Russell Associates, dealing with matters relating to people with disabilities. He also became an important player in veteran disability issues, serving as national commander of American Veterans and president of the World Veterans Federation. In 1964, he was appointed chairman of a government committee that helped bring about groundbreaking anti-discrimination laws, such as the 1973 Rehabilitation Act.

The taste for the entertainment industry never quite left Harold, however, and he made many cause-related appearances in nightclubs, sometimes playing piano duets with his hooks, a skill he showed off with Hoagy Carmichael in The Best Years of Our Lives. Before his death on January 29, 2002, Harold also rekindled his interest in film acting, appearing in Inside Moves in 1980 and Dogtown in 1997.

Harold Russell was at the centre of another “first” in Oscar history, one that again demonstrated that he was not quite in sync with Hollywood culture. Ever practical and honest, in 1992, he sold his best supporting actor Oscar to an anonymous bidder for $60,500 in order to pay his wife’s medical bills. The Academy was so incensed it has since brought in a measure that requires all Oscar recipients to sign an agreement that they will not sell their Oscars.

Harold’s response to the controversy was typically straightforward. “I don’t know why anybody would be critical,” he said. “My wife’s health is much more important than sentimental reasons. The movie will be here, even if Oscar isn’t.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement