State of Mind

Big Question

Does Canadian culture need protecting?

Once upon a time, the phrase “Canadian culture” caused eyes to glaze over. The phrase usually followed over-emphatic protests that of course this country had its own culture, prompting suspicions that perhaps it didn’t; perhaps we were just a mash-up of British and American creative trends.

Today, that insecurity has evaporated. But there is no neat definition of Canadian culture. Sometimes it encompasses any artistic endeavour that reflects values on which we pride ourselves, such as inclusivity and tolerance (Hello, CBC’s Little Mosque on the Prairie). Other times it is straight nationalism (such as Charlie Pachter’s images of the Queen on a moose). Most often, it’s simply a laundry list of popular themes — landscape painting, soulful ballads, novels featuring multi-generational families, any art form featuring bears or blizzards.

But we are not all reading the same books, admiring the same paintings, listening to the same music, attending the same theatrical or ballet performances.

While British Columbians embrace the cheerful seascapes of E.J. Hughes, five thousand kilometres away Newfoundlanders admire Christopher Pratt canvases that capture the cold Atlantic light. While immigrant community dramas dominate Ontario bestseller lists, two days drive away on the Prairies it is the travails of Indigenous families that capture readers. And francophone Quebec has developed its own TV, film, pop artists, and literature that are largely unknown in the rest of Canada and completely distinct from the Hollywood machine.

As Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told the New York Times soon after his 2015 election, “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada.”

So a homogenous Canadian culture is unlikely. Yet … there are moments. In the summer of 2016, The Tragically Hip gave Canadians a rare opportunity to imagine that, for just a nanosecond, almost all of us were on the same cultural page. When The Hip — a hugely popular band with no profile outside of Canada — gave their final concert in their hometown Kingston, Ontario, in August 2016, an astonishing one third of all Canadians tuned in on television, radio, or via online streaming during the three-hour broadcast.

Gord Downie, the lead singer now suffering from terminal brain cancer, sang about us: His lyrics are littered with references to Jacques Cartier, prairie winds, frozen lakes, small towns, residential schools, the Rideau Canal.

Why is this important? Given the gulfs between regions, why should we value our artists and performers, let alone allow governments to allocate tax dollars to subsidize them and their access to the public?

This question goes to the heart of our national character. Regardless of Prime Minister Trudeau’s proclamation of Canada as a “post-nation-state” with no core identity, a collective sensibility has quietly evolved in this country since Confederation, in spite of regional differences.

Today’s polling repeatedly shows that, wherever they live, a majority of Canadians attach a high priority to the values of accommodation, human rights, and diversity; we trust government to promote tolerance and to mitigate economic inequality.

These values are in dramatic contrast to those currently reflected elsewhere, particularly in the United States of President Donald Trump. And, as The Tragically Hip concert tour suggested, artists reflect that identity.

Artists help to illuminate our world a little better and to capture our unique sensibility. It has been one of the most significant achievements of the past century and a half. But in a shrinking world Canadian culture and identity remain fragile.

In the early years of the Dominion of Canada, this country remained a colony as far as the arts were concerned. The “vision” came from elsewhere.

Poets borrowed the rhythms of Alfred Tennyson or Algernon Charles Swinburne; painters made Canadian maples look like British oak trees; authors rarely set their novels within the landscape on which they were perched. Ambitious creators and performers fled to New York City or to London, not least because that’s where the publishers, galleries, and audiences were.

At Confederation, the new country had only six museums and no publishing industry or concert hall. Tastemakers in Halifax, Montreal, and Toronto (the only substantial cities of the day) ignored the rich traditions within particular communities, such as the extraordinary artistic skills of Indigenous peoples, the music and songs of rural Quebec, the fiddlers and dancers of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton.

How far we have come! But it took time. A literary culture began to emerge in anglophone Canada with (among others) the “Confederation Poets” — Charles G.D. Roberts, Bliss Carman, Archibald Lampman, and Duncan Campbell Scott. Although traditional in style, their poetry was unmistakably Canadian because they wrote about classic Canadian themes: water, winter, woods.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

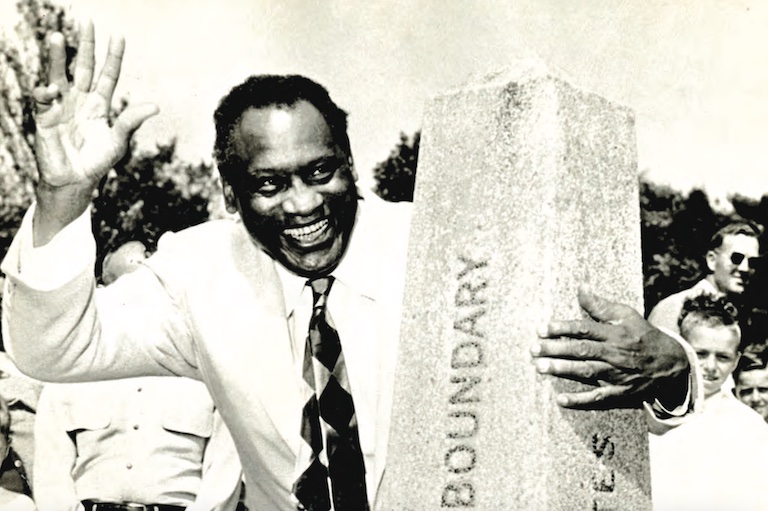

Then came the extraordinary performance artist E. Pauline Johnson, daughter of a Mohawk chief and his English wife, who penned both bloodthirsty ballads about Indigenous warriors and lyrical verse about canoes and sunsets.

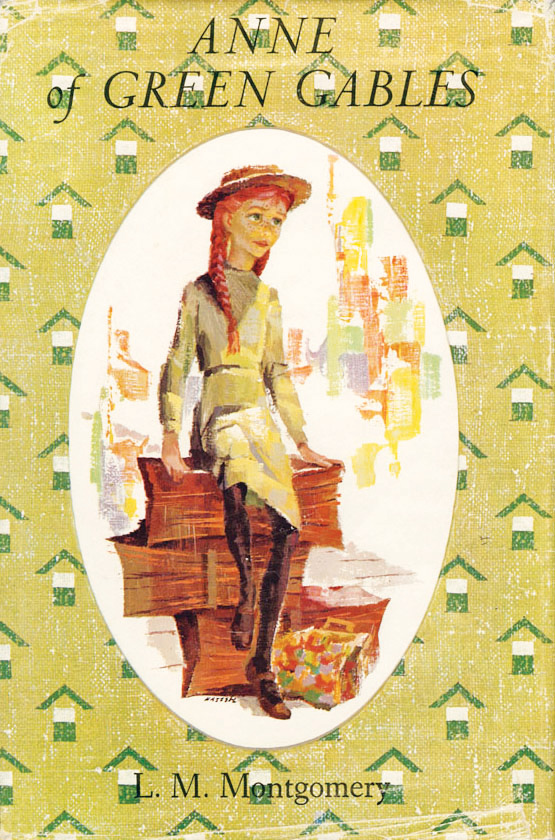

Next, a handful of novelists emerged whose fiction was set in Canada but appealed to English- speaking readers everywhere — Ralph Connor, Lucy Maud Montgomery, Stephen Leacock. But on their home turf, it was slim pickings within a philistine society.

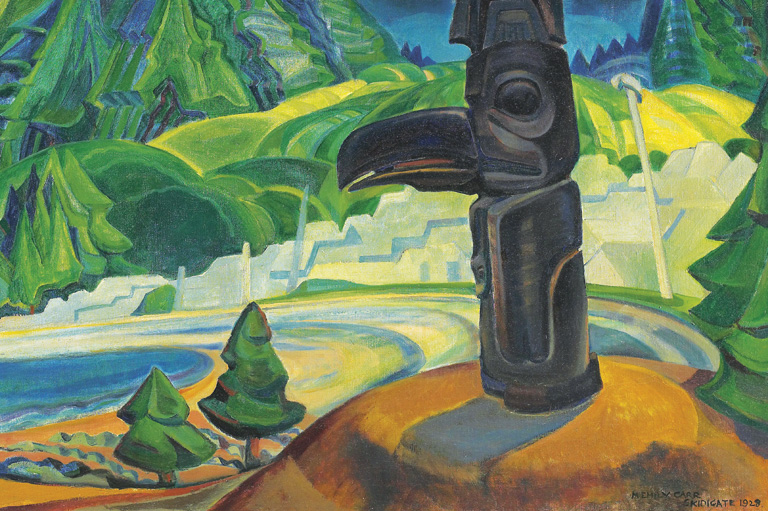

Visual artists were making the same effort to capture on their canvases the dramatic geography of the new Dominion. Group of Seven paintings (many painted in Ontario’s Algonquin Park) have been described by critic Robert Fulford as “our national wallpaper.” In British Columbia, Emily Carr was painting not only the lush rain forest but also the extraordinary creations of the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Nisga’a peoples. But few artists made a living from their work, and cheap reproductions of European art were the most common feature of Canadian parlours.

It takes money to build a national culture. Artists need appreciative audiences: buyers for their books and artworks; ticket purchasers for concerts, ballet performances, and plays; patrons for cultural initiatives; properly financed art schools and music colleges. And, until the middle of the twentieth century, most Canadians were scrambling to make a living.

This was a poor country, and there was neither time nor cash for what were widely regarded as “frills.”

Ottawa, the national capital, boasted no proper public art gallery, no decent museums, and only a small amateur theatre company. For the most part, provincial capitals depended on a handful of local philanthropists to support the arts.

This all changed in the buoyant years after the Second World War.

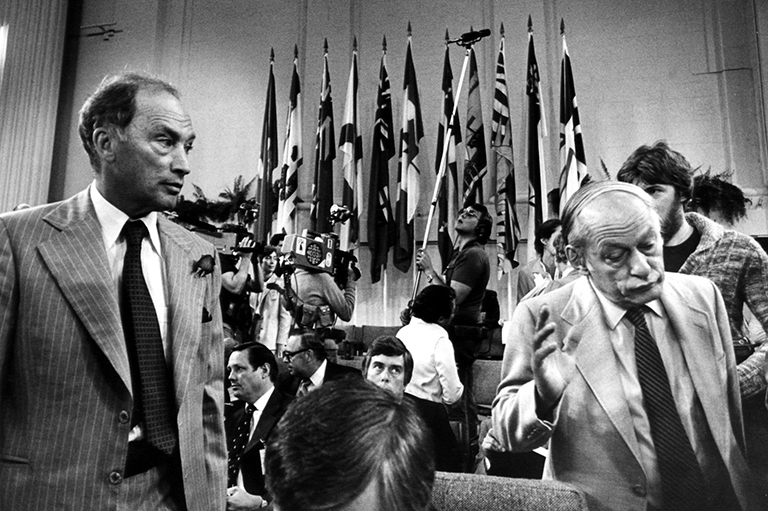

A commitment to building a national culture gained momentum in lockstep with the growth in gross national product. In 1949, the Liberal government in Ottawa appointed the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences, with Vincent Massey (the future Governor General) as chair.

The five commissioners went on a cross-country tour and returned to Ottawa aghast at what they had found. They had heard that the arts were starved and that “the cultural environment is hostile or at least indifferent to the writer.” The commissioners argued in their final report that if Canada was to mature as an independent country it needed state support for the arts in both English and French.

The Massey Commission was a turning point for this country’s artists, as well as for Canadians generally. There were a few political roadblocks — Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent is said to have responded to the report in shock: “Fund ballet dancers?!”

But the postwar economy was booming, fuelling an appetite for cultural distinctiveness. The most important initiative was the Canada Council for the Arts, established in 1957 with a mandate to “foster and promote the study and enjoyment of, and the production of works in, the arts.” The council not only distributed its dollars to artists throughout Canada; it also built support for the idea of the arts as an important element in national identity.

As Margaret Atwood, Canada’s global literary superstar, put it in Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature, “I’m talking about Canada as a state of mind, as the space you inhabit not just with your body but with your head.”

From the 1950s onward, the fizz of national self-discovery exhilarated everybody. Two institutions established in the 1930s, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and the National Film Board, were given more independence and bigger budgets; like the Canada Council, both served anglophone and francophone Canadians.

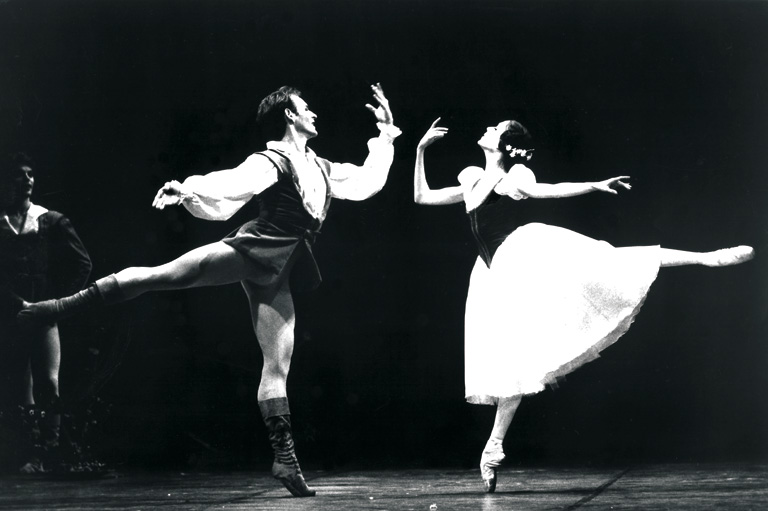

Theatre festivals sprang up across the country, with the Stratford Festival in Ontario as the crown jewel. The Royal Winnipeg Ballet, founded in 1939, developed into a national touring company, and in Toronto, Celia Franca founded the National Ballet of Canada in 1951.

On Canada’s hundredth birthday, the national capital finally got a National Arts Centre, followed a few years later by two important cultural institutions — the National Gallery of Canada and the Canadian Museum of Civilization (now the Canadian Museum of History).

People began to speak of CanLit as an English-language genre in its own right (with a heavy emphasis on heroines who survived against terrible odds). By the late twentieth century, CanLit was flourishing, thanks to government grants and a raft of glittering prizes such as the Scotiabank Giller Prize. When Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2013, there was coast-to-coast chest-thumping.

Postwar Quebec also enjoyed a literary surge, with novelists like Marie-Claire Blais and Nicole Brossard, and playwrights including Gratien Gélinas and Michel Tremblay, rethinking the values of a society that had, up to then, been profoundly traditional. The gulf between anglophone and francophone cultures — what Montreal writer Hugh MacLennan famously called “two solitudes” — deepened; few critics operated in both languages. But both genres had authors who proved adept at widening their appeal and at including the voices of immigrants, such as Ontario’s Rohinton Mistry, Indian-born author of A Fine Balance, and Montreal’s Dany Laferrière, Haitian-born author of Comme faire l’amour avec un nègre sans se fatiguer. The 2016 Scotiabank Giller Prize winner was Do Not Say We Have Nothing, by Madeleine Thien, a Canadian whose parents were of Chinese origin.

By the early years of this century, opera companies, orchestras, chamber music groups, local museums, and art galleries proliferated, thanks to a combination of both private and public-sector funding. Two new national museums were established: the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 in Halifax and the Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg. Carefully designed tax measures and an interlocking system of government subsidies allowed Canadian magazines and journals to “explain Canada to Canadians.” Not all these initiatives thrived, but those that did nurtured creative talent.

One hundred and fifty years after Confederation, Canadian artists and cultural industries seem pretty sturdy; Canada as a “state of mind,” in Atwood’s words, is recognizable. Most of our fellow citizens can name a couple of cultural icons that are uniquely Canadian — not just pop culture idols such as The Tragically Hip or Trailer Park Boys but also high-culture icons such as Tom Thomson, Glenn Gould, Robert Lepage, and Michael Ondaatje.

And the contemporary arts scene reflects a much wider sensibility than the Britain- derived culture of Canada’s first century. Indigenous peoples, so cruelly marginalized for so long, are finding their way into the cultural mainstream today, particularly as authors (Richard Wagamese, Joan Crate), musicians (A Tribe Called Red, Tanya Tagaq), and visual artists (Kenojuak Ashevak, Rebecca Belmore, Kent Monkman).

But nothing lasts forever. In the past few decades, harsh crosswinds have blown through this carefully constructed edifice of creators and spaces, undermining its stability. During economic downturns, right-wing politicians regularly demand cuts to grants to artists and cultural institutions. More recently, the federal government led by Stephen Harper was particularly critical of the CBC, which it perceived both as biased against the Tories and as a waste of money; the national broadcaster’s budget was steadily cut, and there were constant rumours that the government wanted to dismantle it. (The Justin Trudeau government restored its budget.)

At the same time, the tsunami of globalization and digital technology has raised more challenging questions. As Kate Taylor, culture columnist for the Globe and Mail, puts it, “How can a midsized power maintain any notion of cultural sovereignty in the face of the aptly acronymed FANG (that’s Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google).” The Internet allows these U.S.-based companies to drain dry local cultural economies, because profits from advertising, Netflix subscriptions, and online book purchases now flow south.

Canadians who want to create and to market TV shows, video games, documentaries, books, or feature films — projects that collectively raise billions for the economy — scramble to find financing from private and public sources. If those sources shrink, creators will move to where there are larger audiences and more funding, just as their predecessors did one hundred and fifty years ago. Canadian culture will slowly dissolve in the larger North American ocean. Would our unique identity follow?

Canada is not alone in this predicament. Most countries are struggling to protect their distinct identities and cultures against global forces; France is a leader in this battle. But, along with most of its European neighbours, France has developed its own culture over centuries and has relied on language barriers to protect it. In Canada, the national culture remains young and porous, and without government support it could rapidly dwindle.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement