Jazz Man

On April 11, 2000, a sold-out audience at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall was treated to the world premiere of Trail of Dreams: A Canadian Suite by the iconic Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson and the Michel Legrand Strings. The seventy-four-year-old Peterson was seven years removed from a 1993 stroke that affected his left side. But, as he had done over much of his life, Peterson overcame such adversity, dazzling both those who were seeing him for the first time and those who, decades earlier, had witnessed his first musical ode to his homeland on the 1964 album Canadiana Suite.

Peterson, accompanied by bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, guitarist Ulf Wakenius, and drummer Martin Drew, warmed up the crowd with a fantastic first set featuring signatures such as “Night Train.” Then came the moment the audience had been waiting for: As music swelled from a twenty-four-piece string ensemble under Michel Legrand’s direction, Peterson conjured from the piano the twelve songs that made up Trail of Dreams. From the swinging, toe-tapping “Open Spaces” to the airier, textured “Manitoba Minuet,” each “musicscape,” as Peterson described them, vividly captured a region of Canada, creating a rich, aural masterpiece. “Oscar Peterson is a deeply Canadian artist,” Gene Lees wrote in his 1988 biography Oscar Peterson: The Will To Swing. “He uses sound the way [Group of Seven artist] A.Y. Jackson used paint.”

Peterson, who would have turned one hundred this year, told Lees how imposing the piano was. “It’s a lot of instrument,” he said. “You can look down and see the whole keyboard with all its possibilities sitting in front of you. I’m sure it intimidates everyone at some point. It did me.” But, despite the eighty-eight keys staring up at him, Peterson managed to master the instrument with a grace, smoothness, and fluency few jazz artists — even the great ones — ever matched.

“The thing that fascinated me the most was the size of his hands. I kept saying to myself, how is he going to fit them into the keys? His size, but, by the same token, how tender his touch was when he wanted it to be,” said lifelong friend and acclaimed Canadian jazz pianist Oliver Jones. “And how fluid he was. He could’ve been a great classical pianist, I believe. But at that period of time, it wasn’t the time for us to have a black concert pianist.”

article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

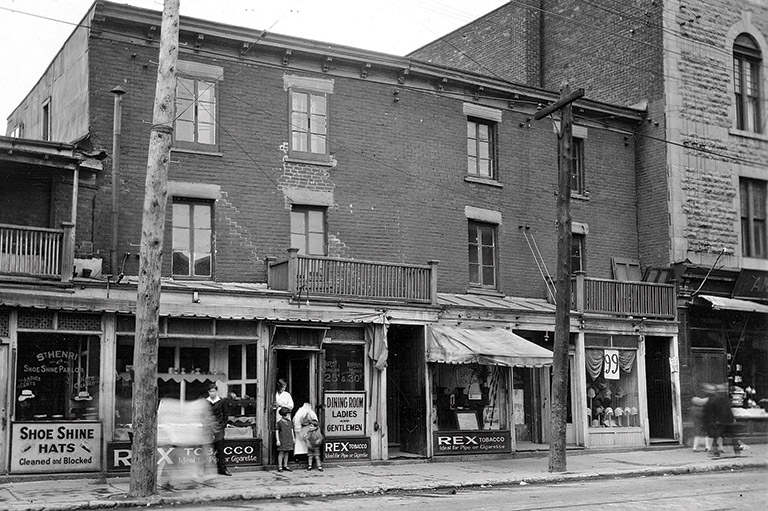

Oscar Emmanuel Peterson was born in Montreal on August 15, 1925. The son of Daniel Peterson, a CPR train porter, and Olive Peterson, who worked as a housekeeper while raising their children, Oscar lived in the city’s Saint-Henri district near the Windsor CPR station. The locale was a melting pot of ethnicities, Peterson said in the 1992 documentary In the Key of Oscar, and it later inspired him to compose the song “Place St. Henri.”

Eager for his five children to have a better life, Daniel instilled discipline and high expectations. “My dad’s philosophy was that in order to overcome all the barriers, we had to do something special,” Peterson said in the documentary. “And Pop seemed to apply that to everything, including the piano.”

Although he played both trumpet and piano early on, Oscar Peterson switched exclusively to piano after he contracted tuberculosis at the age of seven. Peterson spent thirteen months in Montreal’s Children’s Memorial Hospital (now the Montreal Children’s Hospital). He survived. But, tragically, his brother Fred died of the disease as a teenager in 1934.

Peterson developed his innate gift for piano, often practising for many hours a day. Listening to what his older sister, Daisy, played, he would play it back by ear, without sheet music.

Two influential piano instructors helped Peterson flourish. The first was the prolific jazz pianist Louis Hooper, who had played and recorded in Detroit and in New York City’s Harlem neighbourhood before moving to Montreal. Hooper was in awe of the eleven-year-old Oscar’s talent, especially when he heard him playing from memory. Hungarian-born classical pianist Paul de Marky, who worked with Peterson when he was fourteen, encouraged the young man’s self-confidence, both in his technical ability and in his artistic interpretation of the music.

Meanwhile, Jones, who lived down the block from the Peterson family home, often sat on their doorstep just to hear Peterson practice. Jones was about five years old when he first saw the teenaged Peterson perform at Montreal’s Union United Church, the home of one of Canada’s oldest black congregations.

“I knew what time he usually practised, because there was always music coming from the Peterson family home,” Jones said. “So I would sit on the doorstep when it was time to go play baseball or hockey. I would just sit and listen. The rest of them would say, ‘Let’s go and play.’ I wanted to hear more of the piano.”

Fortunately, Jones and Canada heard much more of Oscar Peterson. After winning a countrywide CBC amateur contest at age fourteen, Peterson played weekly on Montreal’s CKAC radio show Fifteen Minutes Piano Rambling, as well as performing on Montreal’s CBC radio affiliate. He later appeared on CBC Radio’s The Happy Gang, a live weekday variety show.

Blossoming artistically, Peterson was inspired by jazz pianists Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum. Wilson’s playing veered from touchingly tender to frenetic almost on a dime. Tatum was so proficient that, on hearing his “Tiger Rag” for the first time, Peterson believed two pianists were performing. Realizing it was Tatum alone, he lost the desire to play for a month. “A total sense of frustration came over me,” Peterson said in his 2002 autobiography A Jazz Odyssey. “First, it was unbelievable to me that this man could play that way. Second, it was obvious that, though blind, he had accomplished pianistically worlds more than I had been able to do with my sight.” Thankfully for all, he returned to the piano.

Advertisement

At seventeen, Peterson wanted to leave high school to pursue a career as a jazz pianist. His father gave his blessing with one caveat: “‘If you’re going to be the best, I’ll let you go,” Peterson, in the 1992 documentary, recalled his father saying. “But you have to be the best. There is no second-best.’”

Another incident occurred after Peterson joined the Johnny Holmes Orchestra, a popular Montreal dance band fronted by trumpeter John Holmes, at the age of seventeen. According to Reva Marin’s biography Oscar: The Life and Music of Oscar Peterson, Montreal’s Ritz-Carlton hotel initially refused to admit Peterson. The hotel backtracked after Holmes threatened to place newspaper notices stating that his orchestra couldn’t perform at the swanky venue because it “didn’t allow blacks.” Peterson said in his autobiography that Holmes refused “any engagement in which my presence was any kind of racial irritant.”

Despite support from his inner circle, Peterson continued to experience both subtle and overt racism. According to Lees’s biography, another incident occurred shortly before Christmas in 1945, when Peterson and a woman each approached the same taxicab on a Montreal street. The passenger exiting the cab turned and punched Peterson, hurling a racist insult. Peterson fell to the ground as the cab drove off with the woman inside it. When Peterson rose and punched the assailant, the man threw a second punch. When Peterson punched back, a nearby police officer told him he was under arrest. “You turned your back when he hit me,” Peterson said. “If you want to take me to the station, you’ll have to use that gun.” The pianist walked away as both the policeman and the attacker looked on. In 1951, something as simple as attempting to get a haircut in Hamilton, Ontario, saw Peterson denied service three times at the same barbershop, creating international headlines.

“Racism is, sadly, an apparent,” John Devenish, musician and host of Toronto’s Jazz FM’s Dinner Jazz, said of Peterson’s generation’s battle with prejudice. “I am captured by the grace in the face of the grossness of racism faced by a generation who had every reason to shrink from the ugliness and hatred. Their fortitude was bolstered by rising above, by always striving to be better-than. They instilled this sensibility on their generation’s children by virtue of example and action.”

In autumn 1947, Peterson left the Johnny Holmes Orchestra to forge his own path, creating a trio featuring bassist Austin Roberts and drummer Clarence Jones (later replaced by Bernard Johnson). Their initial four-month gig at the Alberta Lounge in Montreal’s Alberta Hotel was so well-received that its engagement was extended through September 1949.

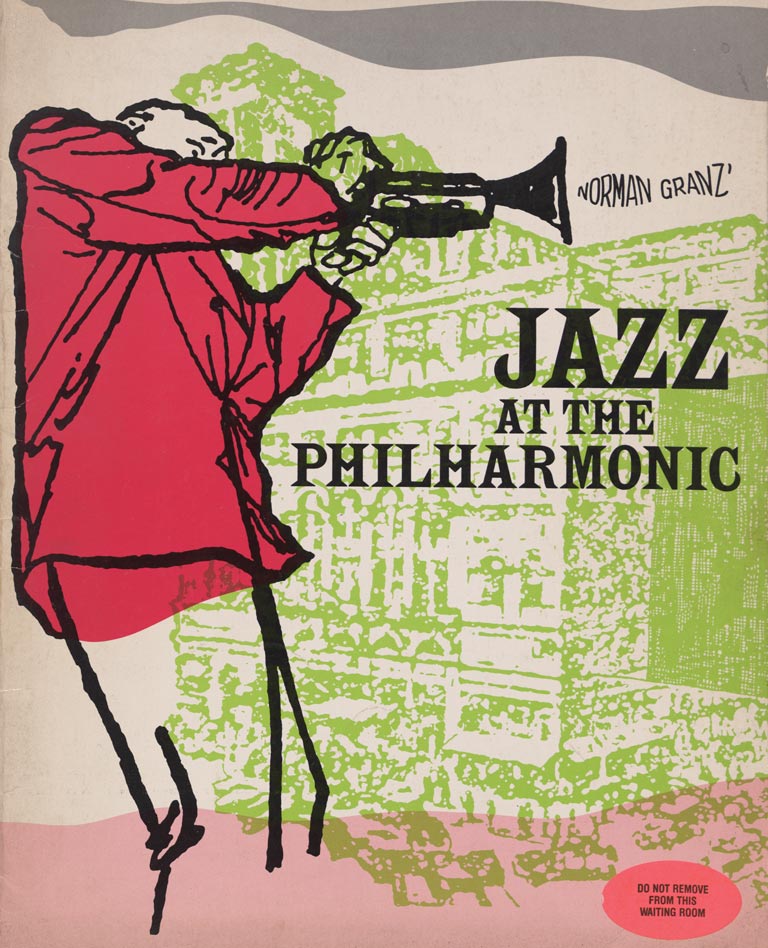

It was an Alberta Lounge performance that caught promoter Norman Granz’s attention. Granz, who became Peterson’s long-time, trusted manager, brought the pianist to New York City’s Carnegie Hall to make his American debut at a star-studded Jazz at the Philharmonic show on September 18, 1949. “He burst upon the American scene with the impact of a new planet,” British jazz writer Richard Palmer wrote in his 1984 monograph Oscar Peterson.

Granz and Peterson formed an airtight friendship and business relationship based on a gentleman’s handshake. Peterson even named one of his sons Norman. Above all, Granz ensured that Black musicians were respected at a time when segregation influenced basic touring logistics like food, lodging, and even access to washrooms. “Granz made more than just a musical statement, he also made a tremendous political statement,” Peterson said in In the Key of Oscar.

Although he had recorded and released several albums with RCA Victor in Canada, Peterson made professional inroads and gained international renown when he formed a trio with guitarist Herb Ellis and bassist Ray Brown. From 1953 to 1958, few musical ensembles possessed such spectacular synergy. Peterson said in his autobiography that the secret lay in “total cohesion and pulsation, where the three of us thought and played as a single unit.” The 1956 album The Oscar Peterson Trio at the Stratford Shakespearean Festival showcased the group’s brilliance. It was one of many highlights of Peterson’s output that decade, including 1952’s Oscar Peterson Plays Duke Ellington and a string of 1959 Songbook recordings celebrating various composers including George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and Duke Ellington.

As busy as Peterson was with touring and recording commitments, he kept the home fires burning, making the most of the time he had with his family. On his eighteenth birthday, he became engaged to Lillie Fraser, and they married in September 1944 at Union United Church.

The couple had five children. “They came a year apart, Lyn, born in 1948, Sharon, 1949, Gay, 1950, Oscar Jr., 1951, and Norman, 1952 — one a year for five years,” Lees wrote. The marriage ended in 1958. “We divorced and I moved from the house after breaking the news to our children, which was the harshest event in my life thus far,” Peterson said in his autobiography. Peterson would marry three more times, having a child, Joel, in 1979 with his third wife, Charlotte Huber, and a daughter, Celine, in 1991 with his fourth wife, Kelly Peterson (born Kelly Greene).

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

A new decade brought Peterson new passions. Besides his hobbies of photography and fly-fishing, Peterson teamed up with Brown and two other jazz musicians to found the Advanced School of Contemporary Music in Toronto. Opening in January 1960, the school gave students hands-on training from Peterson and other notable musicians. Until the school’s closing in 1964, Peterson educated students about jazz music’s five Ts — touch, time, tone, technique, and taste.

His passion for education also extended to social justice. Nothing epitomized this more than his iconic “Hymn to Freedom,” written in 1962 with lyrics by Harriette Hamilton. The song was released on Night Train, an album dedicated to his late father, who had died in 1956. Inspired by the civil-rights protests of the era and the example of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Peterson wrote the song “with hope, because the lyrics personified exactly what I was thinking: When every man joins hands and forever sings in harmony, that’s when we’ll be free,” he said in In The Key of Oscar.

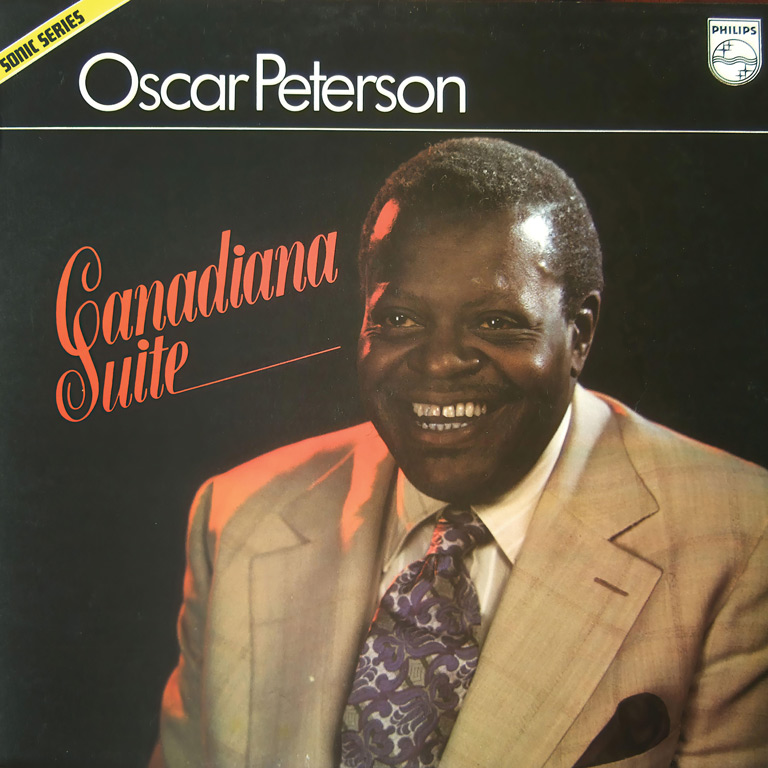

While “Hymn to Freedom” brought Peterson global acclaim, his 1964 album Canadiana Suite exemplified his love of Canada. The effort — composed in 1963 and featuring Peterson, drummer Ed Thigpen, and Brown — included eight songs, each dedicated to a Canadian region and reflecting a railway journey from east to west across the vast landscape.

“It is as spirited as the Aboriginal reverence for this charmed land,” Devenish said. “The music captures vastness and diversity with music impressions blending blues and swing and mood. Peterson, in his own words, put it this way: ‘My profession has taken me to every part of the world, none of them more beautiful than where I live. As a musician, I respond to the harmony and rhythm of life, and when I’m deeply moved it leaves something singing inside me. With a country as large and as full of contrast as Canada, I had a lot of themes to choose from when I wrote the Canadiana Suite. This is my musical portrait of the Canada I love.’”

Peterson became an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1972. “It is still my most important memory, surmounting all the other awards and honours I have received, grateful though I am for them all,” he wrote in his autobiography. “For nothing can surpass recognition by one’s homeland and all the people within its boundaries.” Governor General Jeanne Sauvé made Peterson a Companion of the Order of Canada in 1984, lauding him for his musical career and for being “a staunch champion of the equality of our ethnic minorities”

“He was a proud Canadian,” Jones said. “A lot of people after his career, like so many people around the world, always thought of him as being an American. For years, some of them used to say, ‘How in god’s name did a Canadian get to playing that type of piano?’”

Following another successful decade that earned him three solo Grammy Awards and critical acclaim for his work with guitarist Joe Pass (notably 1974’s The Trio, which won Peterson another Grammy, and 1976’s Porgy and Bess) the pianist continued performing and recording throughout the 1980s. Unfortunately, Peterson suffered a stroke in New York City in May 1993. Realizing he couldn’t play as he had before devastated Peterson. But he persevered, performing at Chicago’s Ravinia Festival in 1994, a return that proved “he remains the pre-eminent pianist in jazz,” the Chicago Tribune said.

Peterson performed some memorable shows in his twilight years. In 2004, Peterson and Jones performed together at the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Montreal International Jazz Festival, seated at pianos across from each other. “It was one of the most memorable concerts I ever had,” Jones said. “After playing all those years, I said to myself, I finally arrived. It’s been eighty-five years I’ve been playing piano in public. I’ve never ran into another pianist who was so dedicated to the instrument.

“I have had the wonderful pleasure of playing opposite Dave Brubeck, and I would say ten of the greatest jazz pianists before, and enjoyed every minute of it. But nothing felt as great to me as sitting and playing with my friend.”

Over his long lifetime, Peterson won many awards and honours. He received seven Grammy Awards for both solo and group performances, including one for lifetime achievement in 1997. He was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and Canada’s Walk of Fame. He holds honorary degrees from several institutions, including the University of Toronto, Berklee College of Music, and the University of the West Indies.

Oscar Peterson died of kidney failure on December 23, 2007, surrounded by family at his Mississauga, Ontario, home. The hundredth anniversary of Peterson’s birth is being celebrated throughout 2025. An Oscar Peterson Centennial Quartet — featuring Wakenius on guitar, bassist Mike Downes, drummer Jim Doxas, and pianist Robi Botos — will play select cities. A concert in Toronto’s prestigious Massey Hall takes place June 14, almost eighty years after Peterson’s Massey Hall debut on March 7, 1946.

The Canadiana Suite

The name of Oscar Peterson’s father, Daniel Peterson, never appears on his son’s landmark 1964 Canadiana Suite album — but he certainly helped to shape the inspiration behind it.

Originally from the West Indies, Daniel Peterson immigrated to Canada in 1917. Two years later, he became a CPR train porter in Montreal. According to Jack Batten’s biography, Oscar Peterson: The Man and His Jazz, the elder Peterson often worked twenty-hour days on the Montreal-to-Vancouver round trip, travelling for five nights and four days in each direction. He retired in the 1950s and died in November 1956, after suffering a massive stroke.

Although gone, he wasn’t forgotten when the album was created. “Those pieces are like views from a train window; or perhaps memories of a father’s descriptions of the land when he would come home from his journeys and supervise his son’s piano lessons,” Gene Lees, who wrote the album’s liner notes, remarked in his 1988 biography Oscar Peterson: The Will to Swing.

“Oscar Peterson’s Canadiana Suite, composed in 1963, is a suite of eight pieces linked by the country they musically express and just as rich as the nation’s diverse collective of its people and regions,” Toronto’s Jazz FM91 radio host John Devenish said. “It moves listeners across the Canadian landscape from the Maritimes [‘Ballad to the East’], through the Laurentian Mountains [‘Laurentide Waltz’], to Montreal [‘Place St. Henri’], then Toronto [‘Hogtown Blues’], Manitoba [‘Wheatland’], Saskatchewan [‘Blues of the Prairies’], Calgary [‘March Past’], and finally British Columbia [‘Land of the Misty Giants’].”

The Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame calls the album “a thoughtful blending of blues and swing, altering rhythm and mood as the mythical railway travels across the nation.” Peterson performed the suite on CBC’s The Wayne and Shuster Hour in 1964. He premiered it live the same year in Charlottetown as Prince Edward Island celebrated the centennial of the 1864 Charlottetown Conference on Confederation. — Jason MacNeil

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement