Haute Cuisine in New France

The following is a true account of an event that took place in Montreal, then known as Ville-Marie, on December 25, 1665. That year, the plague had killed more than 80,000 Londoners, Philip IV of Spain had died and the Second Anglo-Dutch war had begun. The first companies of the elite Carignan-Salières Regiment had arrived in New France in June to protect the colony from the Iroquois invasion. A young drummer, Claude de Mousson, was a real person who was part of that regiment.

When we think of New France, images of a rustic lifestyle often spring to mind. We think of the first settlers who cleared the land and the coureurs des bois (runners of the woods). Although the pioneers had a tough life, that particular depiction of the past doesn’t quite reflect the reality. Some of the French men attracted to New France were senior state officials. Their need to live in Quebec as they did in Paris demanded a certain level of luxury that they displayed ostentatiously for their compatriots to envy … or copy.

The colonists had simpler habits, but many already had “possessions” in France: a house, furniture, an expected inheritance, or the residue of an estate. They took with them things they liked, even food items and utensils they feared they would not find in Canada. These French people were familiar with coffee and chocolate, candied and dried fruit, olive oil from Spain and Provence, Bayonne ham, fine jams, wine, rum, and beer. In the seventeenth century, none could forget the delicate flavours of the feasts that were laid out at Christmas in France.

At the end of 1665, there was a young drummer—a soldier whose task it was to beat out the rhythm for the troops—living in Montreal. His name was Claude de Mousson. He belonged to the who’s who of French society, which was probably the reason he was invited to spend Christmas with the dignitaries in Ville-Marie, the most famous of whom were Jeanne Mance, co-founder of Ville-Marie, and Marguerite Bourgeoys, who founded the first teaching community in Montreal.

During the day of December 25,1665, after celebrating a very joyous Christmas, Claude took a break to write to his mother.

Based on his account, we understand that a little before midnight on the evening of December 24 into December 25, the inhabitants of Ville-Marie came out onto the paths leading to a simple chapel built on Saint-Paul Street near Hôtel-Dieu Hospital. The French and the Algonquin were dressed in all their finery—the latter wearing “clothing made from deer hide, decorated with cowries and fur pelts.”

After the mass, Claude de Mousson wrote: We were all invited to a highly civil feast by the Abbot, who received us, and some notable guests, at the seigneurial castle.”

The menu presented to the dignitaries of Ville-Marie was definitely enough to whet the appetite and delay sleep. “The Abbot regaled us with a pie filled with young pigeon. The ortolan pâté could not have been any better. And well, if I may be so bold, I think the Prince de Condé’s chief steward, Vatel himself, was most impressed. We even had sweetened bread with raisins and candied lemon rind. We had wine and beer to drink.” This is how we discovered that the great French chef François Vatel—who would commit suicide at the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte on April 24, 1671, in the midst of preparing an impossibly demanding series of feasts for King Louis XIV and his entourage—was already famous deep inside a colony, and was possibly already serving as an inspiration.

The guests had stayed up late and, shortly before leaving the seigneurial abode, they made many toasts: “A toast to Spanish wine, to the health of the King and Queen, the Queen Mother, and the entire royal family.”

Full, and maybe bordering on inebriation, Claude de Mousson then attended the dawn and day masses. It was customary for the religious to attend all three masses. The church vibrated under the devotional prayers, and hymn followed hymn, sung in French as well as in Algonquin “by a tribe from the Outaouais River,” wrote de Mousson.

“Marquise,” de Mousson added, “I would have so loved for you to hear them. They sang earnestly, especially the women.”

He probably did not get to sleep before late on the morning of December 25, as the drummers and flutists in the regiment had been ordered “to play a dawn serenade to the commander of the area, the colonel, and Abbot Souart, the representative of the lords.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The Church’s Cheese

Quebec’s famed Oka cheese is known for its soft creamy flavour and pungent aroma. Oka takes its name from a former Algonquin tribe that named itself after a totemic animal called the okow, or golden pickerel.The cheese had its beginnings when the Cistercians—also known as Trappists—immigrated to Canada in 1881 after being expelled from France. They found refuge with the Sulpician Order in Montreal, which offered the monks a parcel of land in the Lake of Two Mountains area near Oka, Quebec. Within a few years, an agricultural school was created and Oka cheese was born. The cheese’s distinctive flavour comes from a special curing process in which cheese rounds are painted with brine and left to age in cellars.

—Christopher Webb

Foodways of the First Nations

Wild Rice Moon Harvest

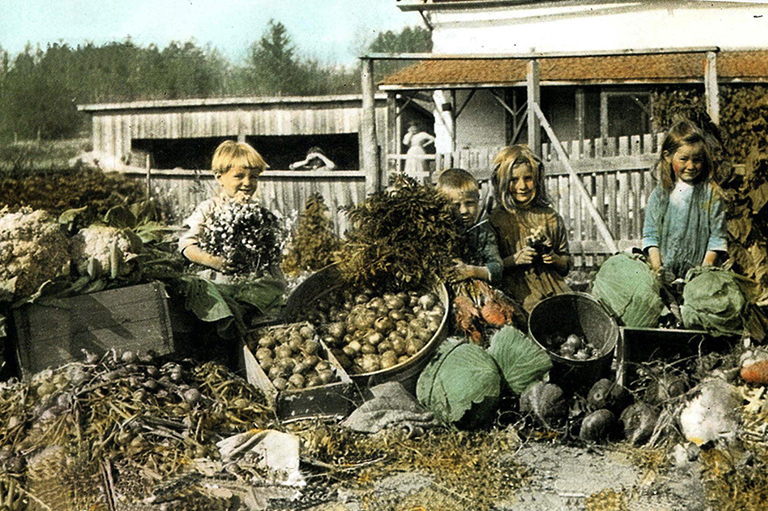

For the Qjibwa Nation, the wild rice harvest was so significant they named a month of their autumn calendar “wild rice moon.” Typically, women and children moved through rivers and lakes in the northern Great Lakes region, bending and pounding the stalks to shake out the grain.

Wild rice—which is actually a type of grass and not true rice—was used by First Nations to thicken soups, dressed with maple syrup, or used in a dish called tassi-manonny, a mixture of rice, corn, and fish.

Corn for the Confederacy

Corn was an essential food for the Iroquois. Along with beans and squash, it was referred to as one of the “three sisters” of food. The grain made its way north along First Nations trading routes from Central America, where it was first cultivated around 5500 BCE.

Corn was roasted or steamed, buried and fermented, dried, ground into flour and made into popcorn. The Iroquois even prepared corn coffee, used corn oil to prevent dandruff, and utilised corn in a number of medicines and poultices.

Sugar Bush Blessings

In spring, First Nations in Eastern and Central Canada would wait for the “sugar moon,” a blessed sign from the Great Creator that marked the start of the maple sap harvest. The Iroquois and other Great Lakes nations would hold great ceremonies, building a large fire at the foot of the biggest maple in the village.

The sap was placed in wooden containers, hot rocks were dropped into it, and it was then kneaded until it was a thick, creamy syrup. The syrup was most frequently used as a sweetener for soups, meat, and wild rice.

—Christopher Webb

The Way We Ate

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.