Food Fit for an Uprising

Upper Canada was only four decades old when the fictional “Ellen” arrived in Toronto in the mid-1830s. The Bird-in-Hand Inn she worked at was a real place at the top of Yonge Street. Her neighbours, the Humberstones and Gibsons, were actual inhabitants. Her fictional letter was written on the eve of what was about to become known as the 1837 Rebellion.

Bird-in-Hand Inn

Newton Brook, Yonge Street

York County, Upper Canada

October 12, 1837

My dear sister Emily:

When I recall the date of my last letter to you I am ashamed that my pen has been idle so long. I hope you will forgive me. Now I am well settled into my new home with our kinsfolk John and Lucy Finch. This inn stands on a very busy road and is held in high esteem by all: newcomers, farmers, and travellers on the stage daily from Toronto (lately York) to Holland Landing, so we never know how many will be at table. Young Fanny, eleven, and her brother Peter, fourteen, from a nearby farm family, are still helping us, else we three could never manage.

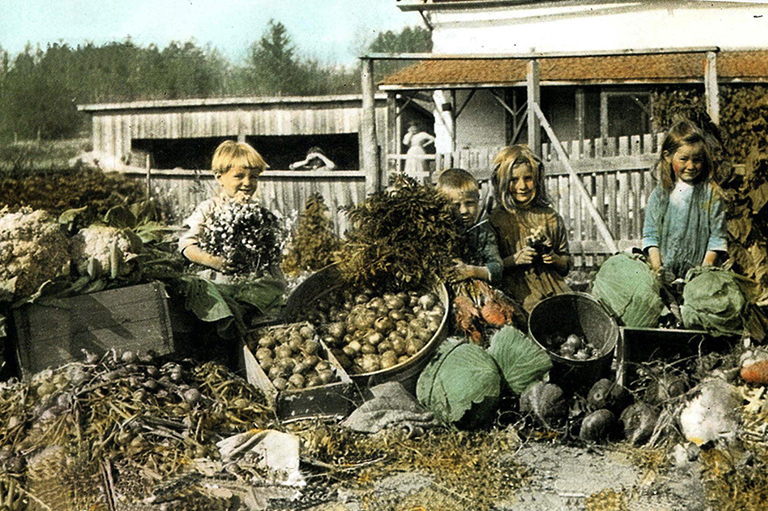

We have now what is called Indian summer, with mosquitoes gone and warm pleasant days, and we womenfolk have been busy harvesting potatoes, onions, carrots, parsnips, and turnips, and packing in sand and sawdust, while Peter has been picking and storing our apples and pears in clean, dry straw. We have made many crocks of beet and cucumber pickles, and after we dried some of our apples, pumpkins, and squash, we stored them in stoneware, too. We are fortunate that young Tom Humberstone and his bride, Sarah Wilson from Markham, are near neighbours. He is a potter and learned his craft from his father at York Mills. One night we heard an uproar with horns, pans, and shouts that set our dogs barking. This is called a shivaree and the visitors expect a treat or money to buy one, so Humberstone gave them some coin and they were soon in our barroom buying a round of whisky.

These last few days we have been all aflutter. John learned that a meeting place was needed for the farmers hereabouts to plan what measures could be taken against the Family Compact. Surveyor David Gibson, our neighbour down at Willow Dale, travels much and tells us this is the well-to-do society in town who give all land, positions, and offices to their family and friends, causing much hardship on others. When we heard the farmers were coming, we looked to our supplies and then hurried to mix and set overnight in the dough box an extra batch of bread made with flour from York Mills and yeast from our own hops. In the morning, I fired up both outdoor and indoor ovens and, while they were heating, set young Fanny to churning. And thankfully, she had butter within the hour. She has become skilful at draining off the buttermilk, washing the butter, adding salt, and storing it in tubs and firkins in the larder. Meanwhile, I was kneading down the bread and shaping it into loaves. Lucy made a clever dish called save-all pie, using up all the leftover joints and bones of meat and fowl combined with our vegetables, cut up and put in a great kettle to boil with some flour and herbs.

As soon as my bread was safely placed in the outdoor oven, I made a large basin of pastry for Lucy’s pies. We slid the five deep-dish pies into the indoor oven and turned our hands to making a crookneck pudding, a mixture of squash, apples, bread crumbs, milk, beaten eggs, and dried herbs. We sweetened it with maple sugar and baked it for over an hour as the oven was cooling fast. We then made a great cauldron of potato soup and had it bubbling by the time darkness fell and the men began to arrive. Nearly four score arrived and Peter was hard-pressed to find stabling for all.

We dished up great bowls of soup as soon as they sat at table, and then brought out the main dishes. There were flagons of ale and strong lashings of tea for those who had taken the pledge. As soon as they finished eating, we cleared the tables and left them to their discourse, as we could hear their voices long into the night. I know not what will happen next, for those men were all sore perplexed.

Next week Lucy and I will go to town, with Peter driving the small wagon, to bring back some of the supplies we will need for the Christmas baking. I am told there are many travellers at Christmas and the New Year, and if there is a blizzard the inn will be overfull, so we must be prepared. Thankfully, there are always on hand here plenty of spirits to season some dishes when needed. We will visit the best stores on King Street for dried fruit, as well as oranges, lemons, and many spices for our crocks of minced meat for pies, and, of course, our cakes and puddings, too.

I am tired now and must say good night, but I will watch for your next letter with news from our family and friends in Lincolnshire.

Your loving sister, Ellen

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Bits and bites

- In the winter of 1535-36, explorer Jacques Cartier’s 110-man crew lived almost entirely on dried or salted meat. Nearly all developed scurvy, and twenty-five died. The Hurons of the St. Lawrence offered them a cure—a tea made from the twigs and bark of what was likely eastern white cedar. Turns out the concoction contained much-needed vitamin C.

- In the late 1800s, the aboriginal people of the North American Plains stood among the tallest on earth, with men averaging five foot eight inches, according to a study by Ohio State University published in 2001. Researchers credit, in part, a varied diet rich in native plants and wild game.

- During the 1920s, Canada had the highest infant mortality rate among industrialized countries. Part of the reason was a decline in breastfeeding, in favour of the convenience of feeding infants cow’s milk. Milk was often obtained from tuberculosis-infected cattle in unsanitary barns, and then stored without refrigeration. The federal government in the 1920s issued its first dietary guidelines, encouraging women to breastfeed.

- In the 1960s, the incidence of rickets among Quebec’s infants was said to be the highest in the western world. Rickets—characterized by soft bones, bowlegs and spinal curvatures—is linked to a vitamin D deficiency. Dr. Charles Scriver, of Montreal Children’s Hospital, successfully campaigned to have the vitamin added to bottled milk, which is believed to have led to 500 fewer cases per year in Canada.

Baking beaver tails

Before Beaver Tails were brushed with butter and bedecked with cinnamon and sugar, the real thing was blistered over an open fire and boiled in a pot of beans.

The beaver-tail bean dish was modified in the nineteenth century by a quick-to-bake dough recipe for those caught camping without a frying pan—and with no actual beaver tail in hand. The dough was shaped into a long, narrow loaf, resembling a beaver’s tail, stuck on a stick, and baked over a campfire.

Today, Beaver Tails made of dough and fried in oil have become a favourite at events such as Winterlude, Ottawa’s winter festival.

—Christopher Webb

The Way We Ate

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!