Selling the Prairie Good Life

-

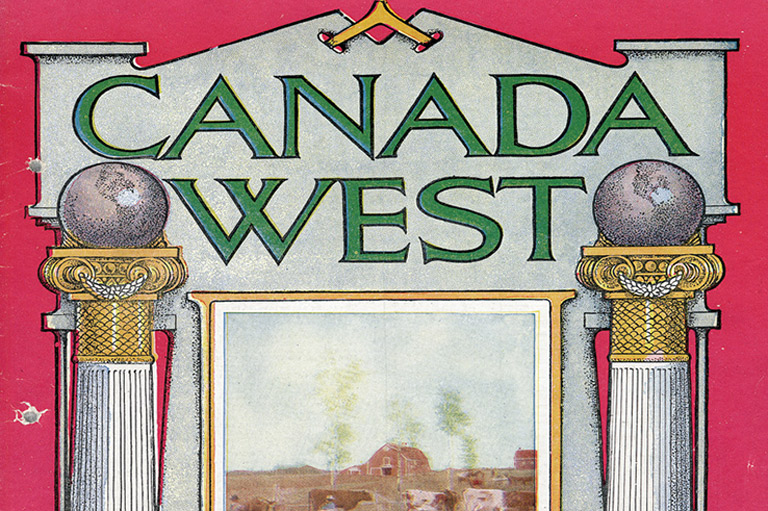

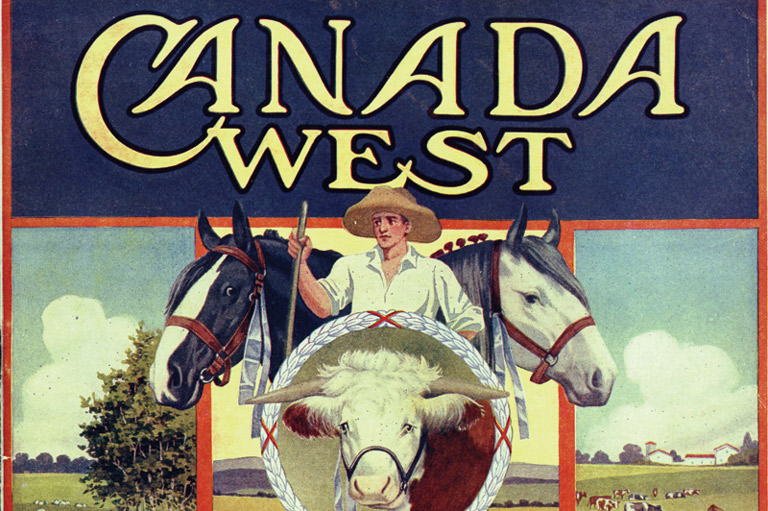

1909 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1909 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

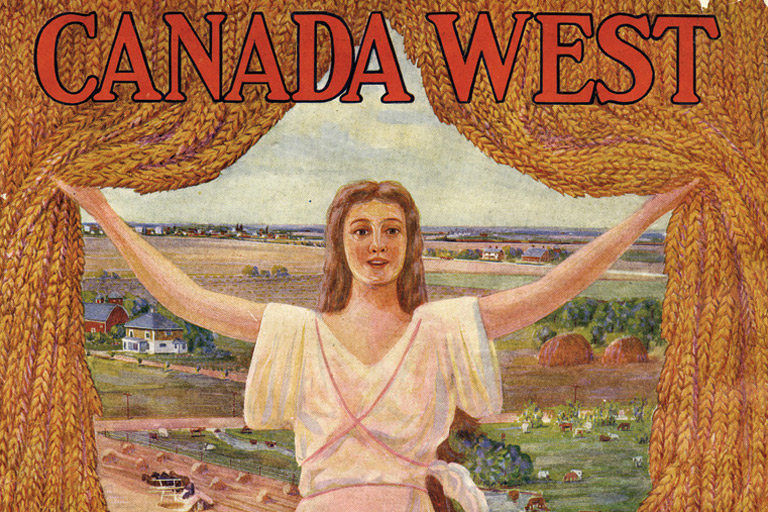

1913 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1913 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

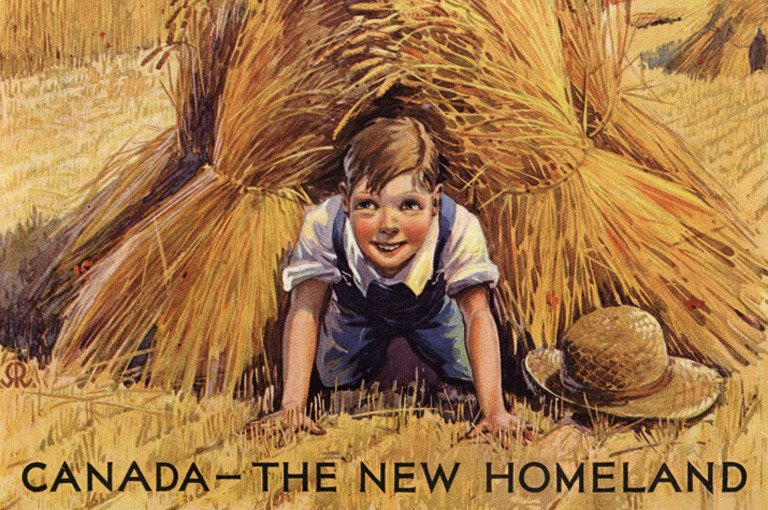

1915 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1915 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

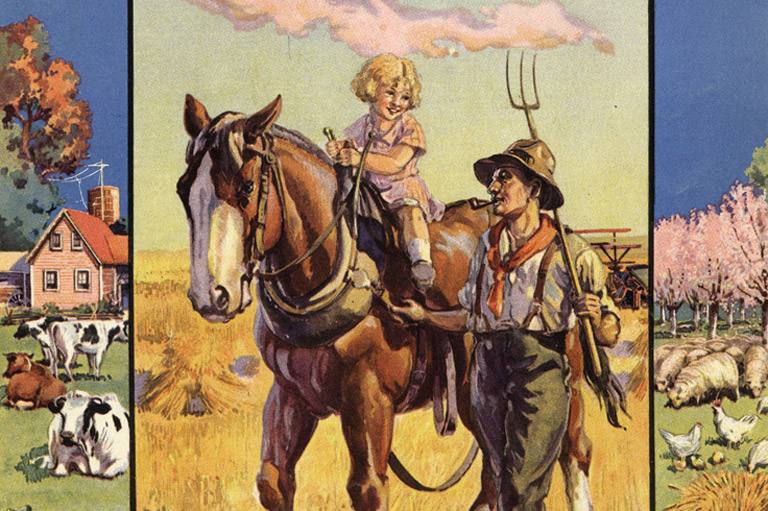

1921 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1921 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

1922 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1922 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

1923 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1923 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

1923 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1923 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

1925 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1925 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

1927 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1927 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives -

1927 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

1927 Canada West magazine cover.Glenbow Archives

Living is cheap; climate is good; education and land are free.”

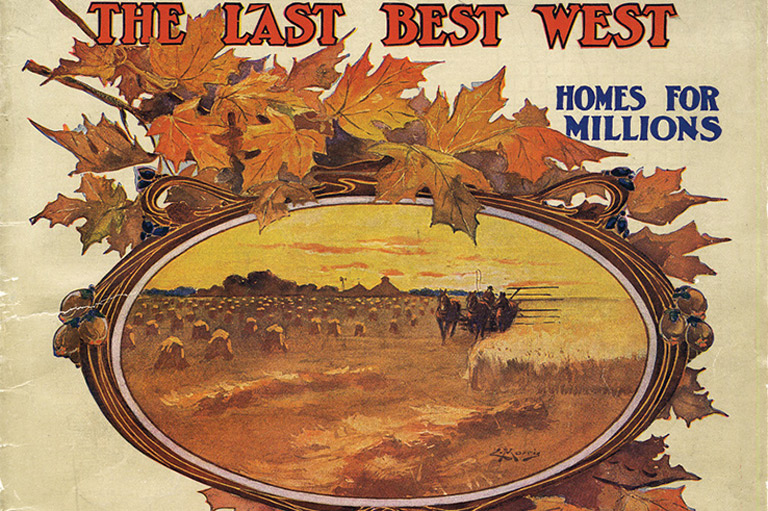

So proclaimed Canada West: The Last Best West magazine in 1910. More promotional brochure for immigration than magazine, it was part of the Canadian government’s drive to attract skilled farmers–British and American immigrants were primarily targeted–to settle and till the soils of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, and turn the land into a cornucopia to feed industrialized eastern Canada and Europe.

Sir John A. Macdonald thought the best way to encourage eastern industrial growth was to establish reliable food production for its growing population on Canadian soil. The ideal agricultural society envisioned by government officials was modern, highly developed, and based on family values; this agenda was articulated in their magazine, considered by immigration agents to be the most useful publication for promoting the West.

With artistic covers portraying an idyllic prairie life of blue skies, golden crops, happy families, friendly neighbours, sunshine, and independence, Canada West was packed with advice for the prospective pioneer. Unlike our modern world of empty advertising spin, and though Canada West had purely promotional ambitions, its success hinged on providing practical information.

Hints abounded, from "For the Man Who Has Less than $300" (this man had better work for wages the first year) to "The Man Who Has $600" (get hold of your 160 homestead acres at once and build your shack) to "What $1,200 Will Buy" (this would provide fairly decent equipment and include one stubble plough at $20).

For the land-hungry homesteader, it offered detailed colour maps of each of the four provinces, growing in later editions to four-page foldouts, which included the checkerboards of surveyed township borders showing where new farmland was available and its proximity to rivers, towns, roads, and railways.

Canada West contained everything the Canadian government thought the prospective farm owner needed to know. Issues repackaged the same message, often running the same kinds of articles every year: statistics on farm yields; information on railways, telephones, immigration, homesteading, schools, building materials, climate, cattle, and hog prices; river and lake access; land and customs regulations; different church denominations; freight rates; and much more.

Issues always included a string of success stories and testimonials, such as one provided by an American newcomer who enthused, "I make five times per acre what I made in Iowa."

In the late decades of the nineteenth century, Canada’s population was heavily weighted in the five eastern provinces: Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. Eastern Canada boasted some large urban centres, but the future of the country depended on attracting farmers to settle the West.

Not only did Ottawa want agriculture to flourish, it also wanted to populate the West to bolster a political stronghold. Concerned about the population imbalance, the government began a fervent campaign to promote western settlement.

Though the approach had been haphazard in the past, Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal leadership in 1896 made great strides to boost immigration. They had a great product to sell: more than 100 million acres of fertile land lay unbroken and ready for habitation.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1899 the federal Immigration Branch of the Department of the Interior published a document entitled Western Canada, which became the template for Canada West. Designed by Rand McNally under the Immigration Branch’s direction, the publication mainly targeted settlers to relocate to the three Prairie provinces; most of the articles, covers, and photographs focused on farming the plains (each issue also offered a section on British Columbia that emphasized fruit and berry growing as well as mixed farming).

Private shipping and railway companies such as the White Star Line and Canadian Pacific had their own immigration campaigns, as there was money to be made transporting eager young men and women and their belongings to their new homes in the West. The CPR was also in the business of selling land.

But Canada West was the government’s own project, and was considered a more comprehensive publication, unlike the others, which were apt to promote only one region. British and American immigration agents favoured it in their efforts to persuade settlers to come.

And come they did. Between 1896 and 1914, more than two million settlers from Europe and the United States poured into the prairies in the greatest wave of immigration in Canadian history. By 1901, of the more than five million in Canada, almost 700,000 (12 percent) were immigrants (not born in Canada).

About one-quarter of the immigrant population had arrived in the previous five years. Immigrants from the British Isles made up 57 percent; from America, 19 percent; Germany, 4 percent; and China, 2.5 percent. Smaller numbers came from Japan, Syria, Turkey, and the West Indies. However, in terms of "origin," 96 percent of the population was of European descent.

The year 1913 still holds Canada’s record for immigrants – 400,870 arrived that year. But the outbreak of World War I in 1914 put an abrupt end to the rush.

Immigration halted during World War I, in large part because the demand for young men at the front reduced the stream of emigration from Europe. Conscription was another factor. Many Americans intending to homestead in Canada heard rumours that immigrant settlers would be subject to service at His Majesty’s pleasure, and they stayed home to avoid a possible draft.

This "stay-put" tendency prompted a bold, eye-catching headline front and centre on the first page of the 1915 issue: "Canada Practically a Self-Governing Country: Military Service is Voluntary—No Compulsion or Conscription." But the slump persisted, inducing an even stronger plea in the 1916 issue.

A letter from the Honorable William James Roche, minister of the interior, which had been directed to American papers, was reprinted on the first page of Canada West. It blamed the pro-German press for publishing fictitious and defamatory news items to cause friction between the United States and Canada.

Roche maintained, "I, therefore, beg to advise you that all troops from Canada for the war have gone voluntarily ... even were conscription introduced it would apply to Canadian citizens only."

Later in the war, a U.S. draft law restricted American citizens from going to Canada. But after the Armistice, a renewed call was aimed at returning servicemen.

"The end of the war has opened new perspectives of broadened opportunity to all Canada, but particularly to the Canadian West," the first page of the 1919 issue proclaimed.

Pitched at soldiers who had returned home to find original jobs were gone or no longer attractive, the article went on to pronounce, "farm life will doubtless appeal to them ... By following the pursuit of agriculture the returned soldier will continue the cause he so greatly advanced when fighting on the field of battle," referring to the war-shattered nations of Europe that now needed sustenance.

Many soldiers coming home from the horrors of war would have been drawn to the idea of rural tranquility. Canada West oriented itself entirely and wholeheartedly to the rural life—although clearly immigration opportunities would have existed in growing urban centres such as Winnipeg, Saskatoon, and Calgary. But what Canada needed for its plains was farmers, not more business or industrial workers.

Indeed, the magazine strove to dissuade quests for urban prosperity.

Of city life, the 1921 issue wryly observed, "It is the same old grind and the same old routine, with nearly every part of the monthly salary going to present-day maintenance. [The worker] is but a cog in the great commercial wheel and one who has failed to give his true condition proper and just consideration. With an equal loyalty to his daily pursuits, and but a part of the energy displayed in the city, he could reap all the advantages of life with its personal and financial independence by becoming a producer—a farm owner."

In order to discourage settlers from heading to urban centres, the rural life had to be convincingly portrayed as more desirable, even idealized. Efforts were made to appeal to potential settlers on an emotional level, and cover illustrations were the publication’s best tool.

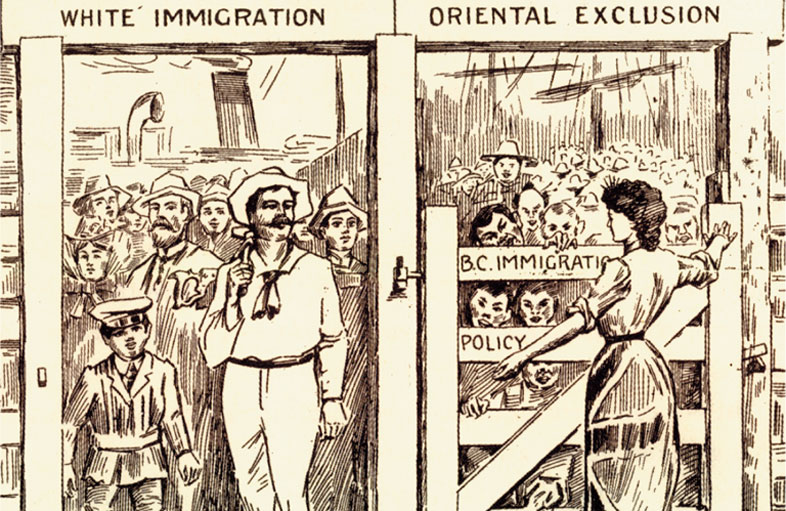

Covers varied more than the articles, and allowed more room for subjectivity. Subliminal messages were visually inscribed, especially the government’s agenda to populate the farms with prosperous white families. This was visually reinforced through cover illustrations.

"The creators took special care with [the covers]," says Laura Detre, an independent scholar from the University of Maine who studies immigration advertising. In her PhD dissertation focusing on Canada West and the Canadian government’s prairie development policy from 1896 to 1918, she observes, "Despite the continuity in the written message, each edition had a different cover."

She explains why. "Covers, could be absorbed passively as they sat on a table, whereas the text required a conscious effort on the part of the recipient to read it. There was certainly more detail inside the publication, and I doubt that anyone decided to immigrate based on one of these covers, but they make a strong first impression."

Detre notes that the earlier covers (up to around 1920) were aimed at men who would be establishing homesteads, but it soon became clear to immigration officials that incoming males were vastly outnumbering females, threatening population growth and the farm family ideal.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

The cover of the 1921 edition reflected this shift and the government’s effort to address the gender imbalance. While the inside material continued to speak to the needs and concerns of men, the cover was clearly designed to appeal to both genders.

It shows a fashionably dressed housewife outside her new farmhouse beckoning to her husband harvesting in the fields. Such an image supported the impression that men could concentrate on fieldwork while women took care of the domestic chores. For women, Detre says, this image has a similar, but subtly different message, as they would identify with the woman in the illustration and feel assured that there was a place for them in farming society.

Indeed, women were specifically targeted in the recruitment campaigns— brochures and documents were created and distributed to sell the appeal of farm life solely to women. The hope was, of course, that they would quickly marry. Detre maintains that, "if all the promises came true, women who immigrated to the Canadian West couldlook forward to lives of leisure, spending a small portion of their day on housework and the majority of their time socializing and relaxing."

Subsequent covers emphasized happy children at play, often in the fields. In reality, most children toiled with farm chores, but the cover images assured newcomers that farms were so prosperous that farmhands could be employed to do the fieldwork.

Canada West was published annually from 1904, as terms for prairie provincehood (namely, Alberta and Saskatchewan) were heating up, to 1930; it was distributed in the United States and Great Britain.

"It was a tool used by immigration agents who worked throughout rural Britain and in the American towns of Biddeford, Maine; Detroit; Toledo; Chicago; Boston; Watertown, South Dakota; Minneapolis and Indianapolis primarily," says Detre.

"There were some small differences between the American and British editions, mostly small changes in phrasing." It was translated into many languages as well, including French, Swedish, German, Dutch, and Hungarian, not for distribution in those countries, but for ethnic communities in the United States.

The magazine’s success is difficult to gauge.

“My sense is that this campaign was generally not as successful as many hoped,” says Detre. For instance, she says, the best estimates claim that as many as one million Americans came to Canada during this period, many of them returning Canadians. But many others returned to the United States at a later point. The European campaign was probably more successful in retaining immigrants, but not all were those the government had envisioned. Detre points out that it was a period of tremendous immigration from Europe, particularly the province of Galicia in Austria-Hungary and Ukraine.

"Some within the Canadian government, such as Clifford Sifton, supported this. Others, such as Sifton’s replacement as minister of the interior, Frank Oliver, opposed Slavic immigration. I believe that the importance of this campaign is that it illustrates the ideal society as envisioned by the white male elite in Ottawa."

Detre feels that the federal government "attempted (unsuccessfully) to engineer a society that reflected their values. Who can say how the Prairie provinces, or Canada in general, would be different today had they been more successful?"

Who They Really Wanted

To populate the Prairies at the turn of the last century, Canada’s Immigration Branch could not afford to be too selective, so it cast a wide net to attract skilled farmers from Europe.

However, promotional campaigns proclaimed who Canadians really wanted. Government recruited immigrants from all over Europe, yet at the same time it tried to curtail the ethnic diversity in a quest for "desirable immigrants." Campaigns such as Canada West were mainly directed at the United States and Britain.

Ethnic hierarchies existed, placing British and American immigrants at the top of the ladder, though there was also division over which of the two groups was most preferable. Some favoured the English, wanting to preserve British institutions and promote an imperial Canadian society, while others felt that Americans would have better farming skills, fearing that urban Englishmen were lazy. Still, British and Americans were consistently the most popular immigrants.

Next, northern Europeans—Scandinavians and Germans—were considered acceptable, followed by eastern Europeans. Southern Europeans were not considered good agriculturalists, but the groups who fared worst were Jews, Asians, and African Americans, showing that culturally embracing attitudes had a long way to go.

Sifton’s Appeal

Clifford Sifton, a young western politician, was added to Wilfred Laurier’s cabinet when he was appointed minister of the interior in 1896. With a mandate to increase immigration, oversee land settlement, and to build "a nation of good farmers," Sifton shaped immigration policy in the first decade of the 1900s with his mission to populate the Prairies.

His strategy was to 1) eliminate roadblocks to settler land grants, 2) offer bonuses to transportation company recruiters, 3) promote and organize tours of the West for journalists, 4) target Britain, Europe, and the United States with brochures to attract farmers in need of land.

These efforts were extremely effective: close to two million people immigrated to Canada during the "Laurier boom," more than half of whom were from Britain. Close on their heels were Americans, followed by a large influx of Ukrainians, Doukhobors, and other groups from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Sifton did not want to attract more city dwellers, feeling it would only exacerbate urban poverty and unemployment. He also instructed immigration agents to discourage the immigration of Jews, Italians, Asians, African Americans, and urban Englishmen.

Instead, Sifton wanted immigration agents to recruit candidates whom he felt would be more likely to endure hardships and remain in Canada through difficult times, such as eastern and central Europeans. When pressed, he was prepared to admit immigrants from places other than Britain and America. In his urgent search for suitable farmers and labourers to populate the Prairies, he described what he sought in the ideal settler:

"When I speak of quality I have in mind something that is quite different from what is in the mind of the average writer or speaker upon the question of immigration. I think that a stalwart peasant in a sheepskin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children, is good quality."

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!