The Lessons of the Anti-Asiatic Riot

When Vancouver’s Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL) decided to put on its inaugural event to protest against continued immigration from China, Japan, and Korea, excitement ran high. The AEL, backed mainly by the Knights of Labour (a non-union conservative labour organization), had been founded on August 12, 1907.

Wanting to make their first event memorable, and thinking that everybody loves a parade, league members decided to put one on, followed by a mass meeting. The event would be held on the first Saturday in September, the weekend after Labour Day.

Mayor Alexander Bethune and several city councillors, all founding members of the AEL, volunteered the use of the city hall, located halfway between Chinatown and Japantown. Religious leaders offered to speak, businesses contributed signs reading “For a White Canada,” and a Major E. Browne stepped forward to lead the parade from the Cambie Street Grounds, north to Hastings Street, and then east to Westminster (now Main Street), after which speeches were to be delivered on the main floor of city hall.

The event was advertised in news reports, and by the time the parade arrived at city hall, a huge crowd had gathered. Crowd estimates vary between four thousand and eight thousand people. The hall held a maximum of two thousand, so thousands milled about on the street in front of the hall.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

After the main speeches inside — at least four delivered by local religious leaders — A.E. Fowler of Seattle’s Japanese and Corean [sic] Exclusion League delivered a rousing speech on the steps of city hall, calling not only for a stop to immigration from Asian countries, but also the expulsion of all people of Asian origin from North America.

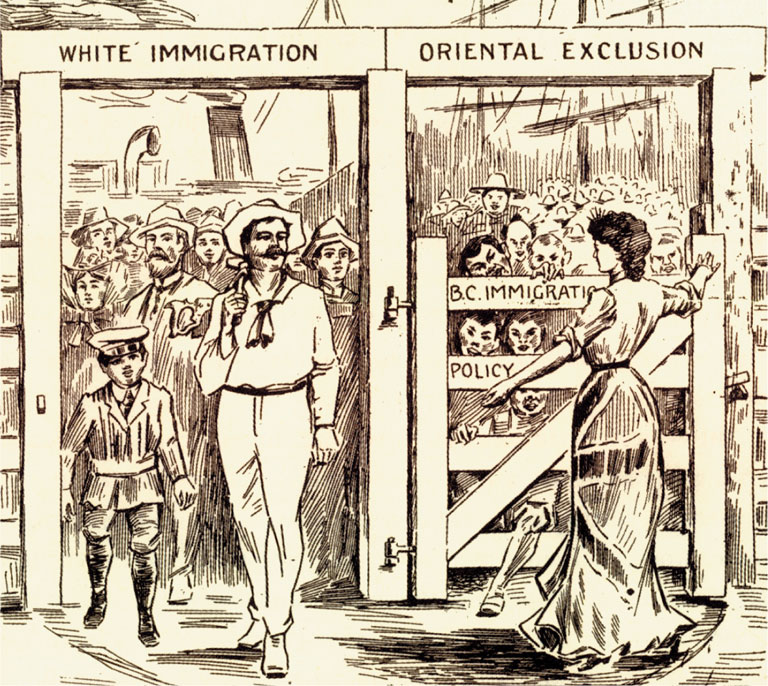

The mob burned Lieutenant Governor Robert Dunsmuir in effigy for his refusal to give royal assent to British Columbia’s 1907 Immigration Act, which was designed to exclude all oriental immigrants from British Columbia in violation of international treaties.

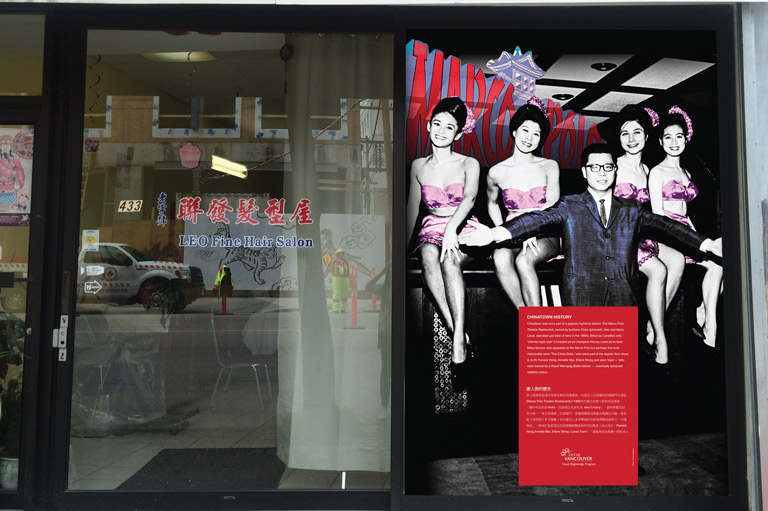

Reports say that after the speeches, a young boy threw a rock through the window of a Chinese merchant’s store — and then all hell broke loose. The surprised Chinese could only lock their doors and set up barricades to protect themselves. Soon every window in Chinatown was broken, and the crowd turned toward “Little Yokohama,” or Nihon Bachi, the few blocks around the Powell Street grounds (now Oppenheimer Park) where Vancouver’s Japanese population lived.

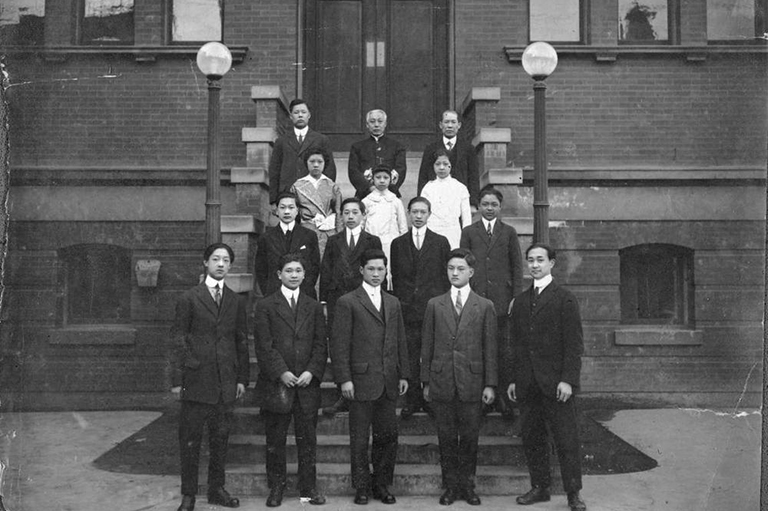

The Japanese were prepared: They had held their own march and organizational meeting the day before, bought weapons, and stocked up on bricks and rocks to defend themselves. Two days of hand-to-hand combat ensued, ending late Monday with the attempted arson of the Japanese Language School on Alexander Street (a newer building now sits on the same site).

The Vancouver police department, consisting of two dozen officers, was overwhelmed, with the crowd freeing most of the rioters taken into custody. Three people were charged, but only one was convicted of any offence. Newspapers openly mocked the efforts of the court and police. Surprisingly, few injuries were reported.

News of the riot flashed around the world, hitting the front pages in Ottawa, New York, and London. All levels of government in Canada made hasty apologies, particularly to the Japanese government — an Imperial ally of Britain and, by extension, her Dominion of Canada.

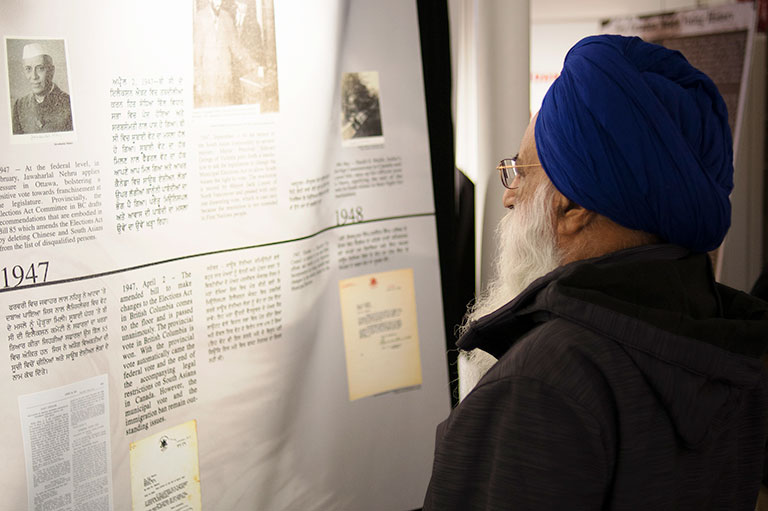

Plans were made for a royal commission, with the ultimate aim of making reparations for damages suffered at the hands of the rioters. William Lyon Mackenzie King, then deputy minister of labour, ultimately chaired two royal commissions, one each for Chinese and Japanese claims. While most claims were honoured, the cost of weapons and ammunition were not paid and no claims from damaged opium factories were reimbursed.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

The royal commissions, however, did not look at the root causes that led to the rioting. Some people blamed the riot on American AEL visitors. Some blamed it on the peak in Asian immigration in 1907 caused by many Chinese and Japanese coming from Hawaii to escape an outbreak of bubonic plague there. Other possible factors include the unseasonably hot weather at the time, and the shortage of jobs due to a downturn in the Vancouver economy.

Certainly, racism was systemic and pervasive in Vancouver at that time in history, and Asian immigrants often elicited hard feelings from non-Asians for providing low-cost labour to the city’s elites.

Lieutenant Governor Dunsmuir, for instance, owned coal mines. He refused royal assent to the Immigration Act not because of the act’s inherent racism, but because the act would have violated treaties the federal government had with Asian governments.

Meanwhile, Robert Browser, the B.C. attorney general who had drawn up the province’s Immigration Act of 1907, was the lawyer for the Nippon Supply Company responsible for writing the contracts to supply Dunsmuir with Asian labour. Bowser profitted from contracting the labour he publicly pledged to exclude from the province.

For British Columbia’s capitalist class, divide and conquer was the goal. Profit depended on cheap labour. Asian labourers denied all rights and privileges were not only cost-beneficial in themselves, but their acceptance of low wages acted as a restraint on the wages of “citizen” employees.

By pitting white labour against Asian labour, the business elite ensured that they were not themselves the targets of agitation. Workers who shared racist sentiments, like those of the Knights of Labour, ultimately worked in the capitalists’ favour.

It was not the sentiments that fuelled the 1907 riots that were unacceptable to the elites — it was the outbreak of violence, which was bad for business.

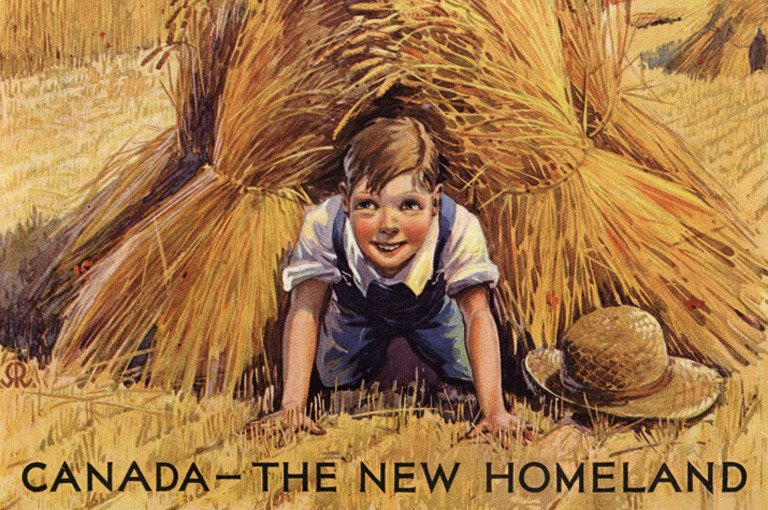

Today, some governments have apologized for racially motivated misdeeds from Canada’s past. But immigration continues to be a difficult issue for policy makers.

Canada needs immigrants and imports labour to fill jobs. We can hope there will never again be anything like an anti-Asian parade or a white riot, but there are still trends, such as racial profiling and clashes over aboriginal land claims, which are laden with racialized discourse.

What if the conditions of our society worsened? What if employers continued to import foreign workers after the economy faltered? Would organized labour join Canadian nationalists to march in the streets? Would they turn against immigrants? Would speeches be made demanding the immediate expulsion of non-landed immigrant labour?

We have two options: to simply live in hope and do nothing; or to learn from the past, take anti-racist action in the present and make a better future for all.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!