Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Women in a Second World War Prison

-

Ethel Rogers as a student about age 21, circa 1925.Courtesy of Marion King

Ethel Rogers as a student about age 21, circa 1925.Courtesy of Marion King -

Ethel Rogers in China while on her world tour, 1933.Courtesy of Marion King

Ethel Rogers in China while on her world tour, 1933.Courtesy of Marion King -

Ethel Rogers married British army doctor Denis Mulvany in India in 1933.Courtesy of Marion King

Ethel Rogers married British army doctor Denis Mulvany in India in 1933.Courtesy of Marion King -

Civilian prisoners in Singapore, circa 1945. They were required to bow to their Japanese captors during daily roll call.Getty

Civilian prisoners in Singapore, circa 1945. They were required to bow to their Japanese captors during daily roll call.Getty -

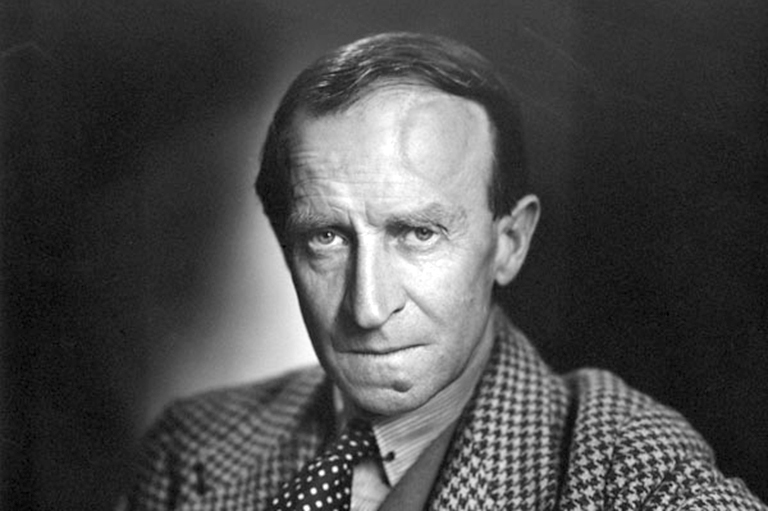

A portrait of Ethel Mulvany done by artist Joan Stanley-Cary while Mulvany was imprisoned in Singapore.Courtesy of Marion King

A portrait of Ethel Mulvany done by artist Joan Stanley-Cary while Mulvany was imprisoned in Singapore.Courtesy of Marion King -

Ethel Muvany's cookbook, a collection of recipes supplied by fellow civilian prisoners in Singapore during the Second World War.Canadian Museum of History

Ethel Muvany's cookbook, a collection of recipes supplied by fellow civilian prisoners in Singapore during the Second World War.Canadian Museum of History -

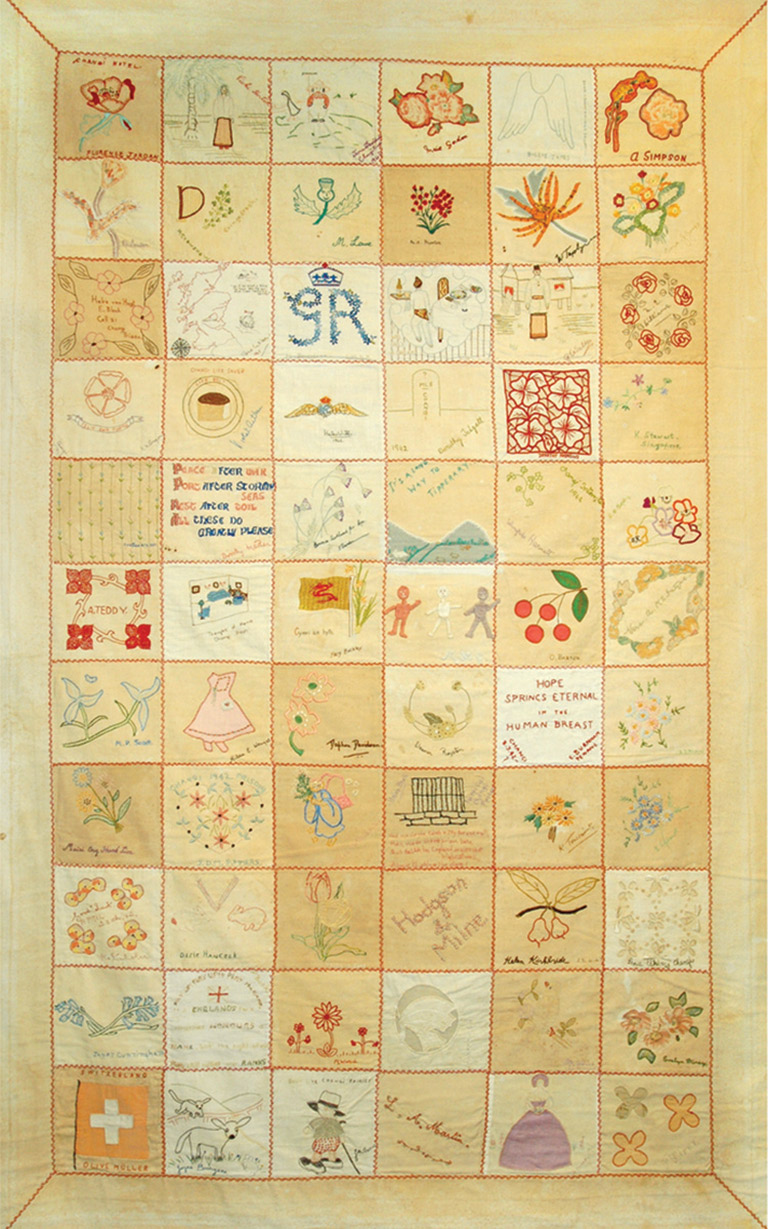

A quilt made at Changi prison in 1942 by female internees.London Red Cross

A quilt made at Changi prison in 1942 by female internees.London Red Cross

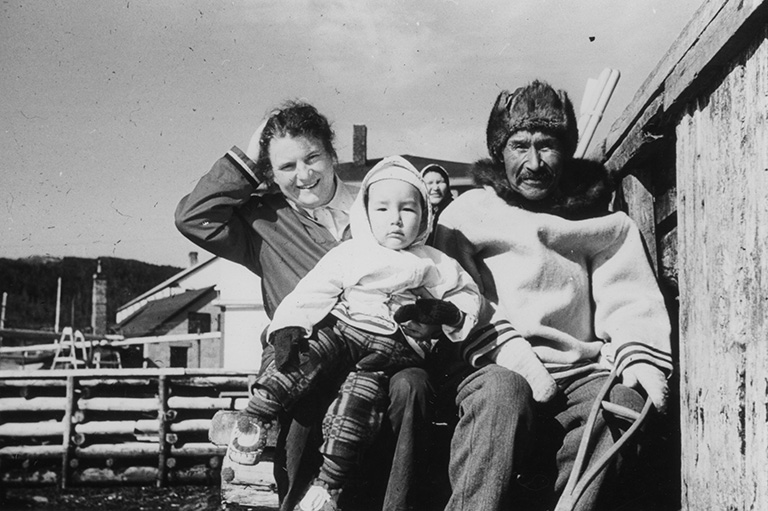

During the Second World War, about 80,000 women and children were imprisoned by the Japanese in camps in the Far East.

Many were the wives or daughters of diplomats. The suffering they experienced was largely forgotten when the war ended. However, the work of some survivors has ensured that their story has not been erased.

One of the survivors was a Canadian woman named Ethel Rogers Mulvany. Mulvany grew up on Ontario’s Manitoulin Island. Then Ethel Rogers, she became a teacher while still in her teens, eventually moving to Toronto to complete her education and become the director of an arts and literature society.

In 1933 the society sent her on a tour of Asia to do an educational survey. While on her travels, she met Denis Mulvany, a British army doctor, whom she married in Lucknow, India.

She followed her husband to Singapore in 1940. Energetic and strong-willed, she was volunteering as an aid worker with the Australian Red Cross when the island was invaded by the Japanese on December 8, 1941.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Mulvany, along with about 1,000 women and 330 children, was taken prisoner and interned at Changi prison, originally designed by British colonial authorities to hold 600 people. Another part of the complex held about 1,100 civilian male prisoners.

Among the survival tactics dreamed up by Mulvany was the holding of imaginary tea parties. The stick-thin, shabbily dressed women would imagine they were dressed to the nines and dining on at immaculately table laden with sumptuous dishes.

The exercise in make-believe served the practical purpose of stimulating the saliva glands. This helped stave off hunger pains — a condition that signalled imminent death.

While in prison, Mulvany was also at the forefront of another morale-building exercise – creating quilts. Women were encouraged to contribute quilt squares with hidden messages that told something of themselves.

The quilts were donated to POW hospitals to reassure others — especially their husbands and fathers imprisoned nearby — that they were alright. The Changi quilts are now held in museums in the United Kingdom and Australia.

After the war, Mulvany returned to Canada, where she compiled nearly 800 recipes recollected by the women at their tea parties and created a cookbook. Sales of the cookbook raised about $18,000 for former prisoners of war hospitalized in Britain.

Today, a rare original copy of the Prisoner of War Cookbook resides at the Canadian War Museum. Rescued from oblivion by the work of Ottawa historian Suzanne Evans, the cookbook was in 2013 republished by the Manitoulin Historical Society.

Through the quilt project — and, to a lesser extent the cookbook — Mulvany left behind a lasting legacy. She helped to ensure the suffering and endurance of the women and children at Changi would not be forgotten.

If you believe that stories of women's history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

More from this issue...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!