Trailblazing Astrophysicist Opened Doors

In the Cavendish Laboratory at England’s prestigious University of Cambridge, a young woman toiled over an experiment in nuclear physics. The year was 1921. Allie Vibert Douglas, a native Montrealer with a master’s degree in physics from McGill University, had won a war memorial scholarship from the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire to study at Cambridge under the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Ernest Rutherford.

Vibert Douglas had chosen to come to Cambridge even though she had no hope of earning a Ph.D. there: The venerable university refused to grant degrees to women until 1948. She was enthralled with the prospect of working under Rutherford, after having heard the charismatic New Zealander speak at a public lecture in 1914. But, working in his lab, she found the famous physicist to be very different from her first impression of him. He banished her to an isolated corner of the laboratory and assigned her a project that dealt with heat emission from a rapidly disintegrating radioactive product. As she struggled with hostile lab mates, failed experiments, and inadequate equipment, Rutherford showed little inclination to help.

Raised by strict Methodists and never one to complain, Vibert Douglas soldiered on. Then, as though to pour salt in her wounds, Rutherford assigned the same project to a new investigator — a Russian named Pyotr Kapitza. The newcomer demanded “none but the very best electrical equipment” and pestered lab assistants in “high and even higher shrill tones to get some piece of apparatus,” Vibert Douglas later recalled in her unpublished memoir, Pilgrims Were We All. Taking an entirely different approach to the one Rutherford had suggested to her, Kapitza achieved quick and spectacular success, and — unlike Vibert Douglas — he earned Rutherford’s “unstinting admiration and full support.”

Disheartened, Vibert Douglas began to doubt whether her future lay in nuclear physics. Cecilia Payne, the only other female physics student at Cambridge, encouraged her to look up from the world of subatomic particles and gaze toward the stars.

Vibert Douglas went on to become one of Canada’s earliest and best-known astrophysicists. The dean of women at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, for two decades, she was also a central player in a network of educated women who helped hundreds of female academics escape Europe during the Second World War. She was named one of eleven “Women of the Century” by the National Council of Jewish Women, admitted to the Order of Canada, and recognized with several honorary doctorates — though she was never granted a degree by the University of Cambridge.

“Her great zeal for astronomy, keen interest in her students, and involvement in fostering international relations made her widely admired and loved,” said her fellow astronomer and friend Helen Sawyer Hogg.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Born in Westmount on the Island of Montreal in 1894, Allie Vibert was a Montrealer through and through — and a lifelong fan of the Montreal Canadiens hockey team. Despite losing her mother and grandfather the year she was born, she experienced a loving and intellectually rich, if somewhat unconventional, upbringing. She and her older brother, George, were raised by a beloved grandmother, Maria Bolton Pearson, and two well-educated aunts, Mary and Mina Douglas, whose surname they later incorporated into their own. Encouraged by her father, George Douglas, the principal of the Wesleyan Theological College, Mina Douglas had been one of the first women to earn a diploma from McGill University in 1877.

As children, Allie and George spent long summers at a cottage in the Thousand Islands, where they learned to swim, row, and sail. Allie Vibert Douglas later recalled that, by contrast with her later teachers, who “seemed afraid of any knowledge outside the prescribed curriculum,” their grandmother and aunts taught them from their “broad range of knowledge and interests.” Their grandmother taught reading, spelling, and religion; their Aunt Mary taught music; while their Aunt Mina focused on science, mathematics, and geography, using a globe to demonstrate “the three motions of the earth: rotation, revolution and the wobble of its axis.” In 1911, the siblings were taken to see Halley’s Comet, and their visitors at the cottage included a venerable Scottish great-uncle who pointed out constellations while reciting poetry.

After high school, Allie Vibert Douglas enrolled in a bachelor’s program in math and physics at McGill University. But in 1914 her grandmother died and her brother George enlisted in the First World War, prompting her and her aunts to join him overseas. She took advantage of wartime labour shortages to secure work as a statistician at the War Office in London, England. As chief of women clerks, she was responsible for generating statistical records and manpower surveys pertaining to military and medical tribunals, exemptions, and special-category enlistments. She streamlined the gathering of this vital information from all across Britain through the judicious use of graphs and instructed her staff on the use of the slide rule. In recognition, she was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire, an astonishing achievement for a woman of only twenty-three.

After the war, Vibert Douglas earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at McGill, then she proceeded to the University of Cambridge, where her initial disappointments in Rutherford’s lab gave way to success in the study of astrophysics under Arthur Stanley Eddington, one of the pioneers in the field. Eddington started her on a statistical study that provided material proof for a question he had already answered theoretically. It led to an article in Monthly Notes of the Royal Astronomical Society and stimulated further research, including her own Ph.D. thesis a few years later.

While at Cambridge, Vibert Douglas developed a strong network of friendships with other women. Although she lived in lodgings with her aunts, she was a member of Cambridge’s Newnham College for Women. She joined the International Federation of University Women (IFUW), an organization dedicated to improving opportunities for university-educated women, who were then still a tiny minority. Besides Payne, she counted among her friends some of the female relatives of the men she worked with. Rutherford’s wife, Mary Georgina Rutherford, and Elizabeth Joyce Shillington Scales, daughter of radiation pioneer Francis Shillington Scales, both lent her emotional support when her Aunt Mary died. Also joining her circle was Eddington’s sister, Winifred Eddington.

There was a fun side to these friendships. An accomplished athlete who had swum competitively at McGill, Vibert Douglas spent much time cycling and rowing to and from lectures, lunches, and teas in the Cambridge area. She enjoyed sports, which at times gave her an entree into the male-dominated world of science, and she joined other Cambridge women in adopting men’s traditions such as rowing. In one memorable end-of-year event, twenty women escaped through a college dorm window to get an early start at canoe races that turned out to be, she later recalled in her memoir, “lots of fun with some comic upsets and much laughter.”

Payne and Vibert Douglas both went on to careers in astrophysics — a new field more welcoming to women than physics — although they remained relatively underpaid and under-recognized for much of their careers. Sensing poor job prospects for women in England and continental Europe, Payne emigrated to the United States to work at Harvard College Observatory and wrote a Ph.D. thesis at Harvard’s Radcliffe College for Women. In it, she contended that stars were composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, an idea so at odds with conventional scientific wisdom that her advisors gave her the grim choice of either downplaying her conclusions or being denied her doctorate. Although she reluctantly chose the doctorate, she was later proven correct. While she went on to make substantial research contributions, Harvard College Observatory did not name her a professor until 1954.

Vibert Douglas took a different route. While she continued to study stellar spectra — earning her Ph.D. at McGill in 1926 — her most enduring contributions would be in popularizing and teaching astrophysics and in helping women to achieve their academic aspirations.

Advertisement

In 1939, after a decade of teaching at McGill, Vibert Douglas left to become dean of women at Queen’s University. While this job entailed a large amount of administrative and domestic work associated with running a women’s residence, and seriously limited teaching and research opportunities, it was the highest position that most academic women, even brilliant ones, could hope for, and it offered some financial and career stability.

A holdover from the days when coeducation was new to Canadian campuses and women’s demoralizing impact was feared, the dean of women was expected to chaperone female students. But Vibert Douglas disliked that role, believing women worked hard to get to university and deserved autonomy. Known to her students as “Dr. D.,” she had a warm smile and a wry sense of humour and often turned a lenient eye to minor misdeeds. She even installed fireproof smoking rooms in the basement of each house, which students nicknamed dens of iniquity. Former student and long-time friend Shirley Brooks recalled that Vibert Douglas once went to bat for a pregnant student, threatening to resign if she were expelled. “If you were in trouble at the university, you’d go to her first.”

A formidable figure on campus, with a firm handshake, a brisk walk, and a capacity for getting things done, she stood up for her students. Interviewed in 1977 when she was in her eighties, she recalled that when male engineering students engaged in their infamous practice of raiding women’s dorms she scolded them: “Why don’t you go to some of your men’s residences, so you can be met fist-for-fist by people of your own strength? You’re just big bullies. You know that the women can’t eject you physically, and so you keep them all on tenterhooks whenever they hear loud shouts and yells.”

Autonomy worked both ways, though, and Vibert Douglas, who arrived at Queen’s the year Canada joined the Second World War, insisted that women students contribute to the war effort. In 1977 she recalled, “I felt that [we should do] anything that could make one a more useful citizen, particularly if there were … some real disaster — if we had sabotage, which wasn’t impossible in those years.” Students attended compulsory lectures on topics like fire control, and they could also choose an evening course in auto mechanics, stenography, or cooking, “anything that would make them more useful as a citizen, that was the idea.” Female students were also required to take St. John Ambulance first-aid and home nursing classes and to do two hours per week of war work — either sewing and knit- ting, working at the canteen, or visiting military hospitals.

Knitting stations were set up for use between classes, and Vibert Douglas fixed up a Red Cross workroom at the top of the old Arts Building, borrowing sewing machines and organizing students to sew hundreds of quilts that were then shipped to underground shelters in London. “Miss [Marion] Ross, the head of physical education for women, put on a very valuable course in basic drill,” Vibert Douglas recalled in the 1977 interview. “And a lot of the students who took that, toward the middle of the war, enlisted, and they either became army, or navy, or air force.”

After the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933 and began enacting its infamous racial laws, cries for help were heard from thousands of women, many of them Jews, who were dismissed from their professional, teaching, and academic jobs. When Nazi Germany annexed Austria and invaded other European countries, the cries for help multiplied. The International Federation of University Women, and particularly its national affiliates in Canada, the United States, and Great Britain, established committees, raised funds, used existing scholarships, and created new ones to help refugees reach safety, resettle, and continue their academic work. Vibert Douglas chaired the War Guests Committee of the Canadian Federation of University Women (CFUW), which helped twenty-three women refugees resettle in Canada. Vibert Douglas welcomed Polish academic Krystyna Zbieranska to Queen’s, where she conducted research into French-Canadian literature, spoke to local groups, and curated an exhibit on Poland’s past and present for the Redpath Library at McGill University.

Anti-Semitism made the task difficult for Vibert Douglas and her colleagues, since many countries, including Canada, had restrictions on Jewish immigration. In one case documented by the British Federation of University Women, Vibert Douglas’s alma mater, McGill University, offered two fellowships to refugee women but accepted gentiles only, as there was a ban on Jewish women at the university’s Royal Victoria College for women.

Despite the challenges, the IFUW’s unique rescue network constituted the only humanitarian effort geared toward the needs of female academic refugees. Other organizations that helped academics focused on prominent researchers, mostly men and most of them specializing in fields useful to the war effort such as nuclear physics, chemistry, and mathematics. By the end of the war, the organization had helped more than five hundred academic women to resettle.

In recognition of Vibert Douglas’s part in this effort, she was elected the first Canadian president of the IFUW in 1947. In extending this honour to a Canadian, the Euro- pean-based organization also wanted to thank Canadian women for the extensive shipments of clothing, specially chosen for individual women and their children who had been displaced by war. In her opening address at the 1950 IFUW biennial, Vibert Douglas referenced the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, challenging members to “work unrelentingly as professional women, as homemakers, and as citizens, each in their own country to narrow this gap between the actual practice and the ideal of human rights through government action, through education, through mass communications, and through home and community influence.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Vibert Douglas used her role as dean of women to advocate for greater academic opportunities for female students, noting in the 1977 interview: “I was rather astounded to find that women were hardly regarded as full members of the university.” Especially piqued that they weren’t admitted to medicine, she brought up the issue with the principal, Robert Wallace, who told her that women “could get the training at McGill or Toronto, and Queen’s didn’t have the facilities.” But Vibert Douglas recommended in her 1941 annual report that Queen’s accept women into medicine, “and the government brought pressure on the university too, because they needed every doctor they could train for overseas and at home.” It worked. By 1944 there were four women registered in medicine at Queen’s, and when she left her post as dean of women in 1959 the number had grown to thirty-two.

She used her influence on individual women as well, including her own niece, Mary Douglas, who had always wanted to study medicine but opted for geography in 1944, as medicine seemed out of reach. After working for the Geological Survey of Canada for ten years, and with Vibert Douglas’s encouragement, she reapplied to medical school and graduated in 1960 as a mature student. She practised for some twenty-five years as a family physician.

Vibert Douglas also pushed for women to be admitted to the Queen’s engineering program, and the first woman was admitted in 1942. She encouraged women to study science, mathematics, and technology, and she even had a mathematical formula engraved above the entrance to Adelaide Hall — the new women’s residence built in 1952 to accommodate the growing number of female students — “to remind the young ladies who passed through the door of the beauty and power of mathematics.”

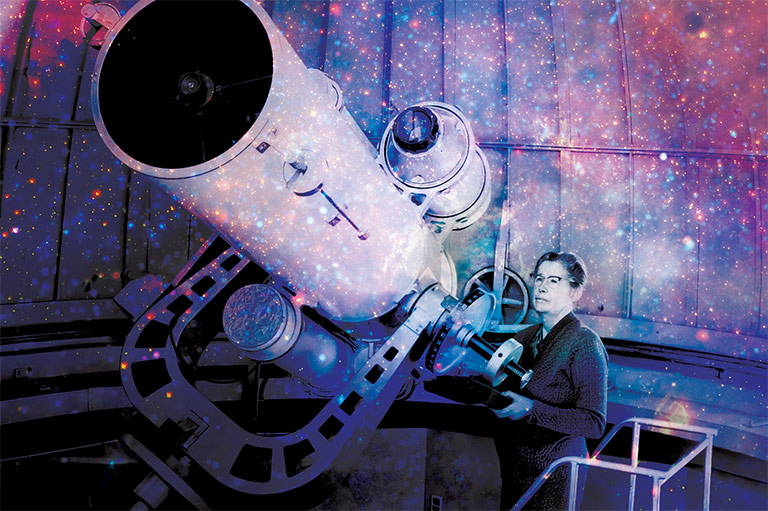

Vibert Douglas pioneered courses in astrophysics at Queen’s, teaching a graduate-level course by the 1950s. She was a strong orator, and, as one colleague noted, her “greatest contribution was the spark of enthusiasm which she passed along to her students.” She loved sharing her experiences of attending international conferences, noting to an interviewer from the Kingston Whig-Standard in 1984 that, “instead of just telling the students about some particular recent advance, you could really get quite enthusiastic about an international meeting at which some subject came up for the first time and the outstanding names in the field were there to discuss it.” She also used innovative teaching aids, including a collection of meteorite specimens that is now on display in Stirling Hall at Queen’s Department of Physics, and photographic plates of stellar spectra that she had created while working at the Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin in the 1920s.

Vibert Douglas’s commitment to popular science remained constant throughout her life, leading her to disagree with the famous physicist Albert Einstein. In an article entitled “My forty minutes with Einstein,” Vibert Douglas quoted Einstein as saying that a scientist who tries to popularize his theories “is a fakir. It is the duty of the scientist to remain obscure.” On the contrary, Vibert Douglas believed that it was her duty to share her knowledge. She published many articles explaining astronomy, physics, and the wonders of solar eclipses in journals such as the Atlantic Monthly. She encouraged amateur and student stargazers, and she was always ready to wish anyone “good seeing” as they peered into telescopes to view the wonders of the night sky.

A frequent visitor to observatories on her many travels, she also served as the secretary-treasurer of the Montreal branch of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (RASC) from 1923 to 1939, and she was the first female president of the RASC from 1943 to 1944. She often brought in renowned speakers, many of them friends she had cultivated at conferences. In 1958, when the old Kingston observatory was moved to the top of Ellis Hall, the new civil engineering building, she helped to define the technical specifications for a new telescope being built through a private donation.

Vibert Douglas retired as dean of women in 1959 but continued to teach until 1964. As she neared retirement from teaching, she wrote a biography of her first mentor called The Life of Arthur Stanley Eddington. It was a tribute to a scientist who, despite his intense reserve, she admired for his “unfailing courtesy, his sympathetic understanding and complete mastery of the subject [of astrophysics] and the mathematical tools with which to cope with its problems.” The work also displayed her subtle and profound understanding of Eddington’s scientific legacy. Reflecting her broad world view, she used many references from the arts, including the first four bars of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony to introduce the chapter on Eddington’s controversial and unfinished book Fundamental Theory.

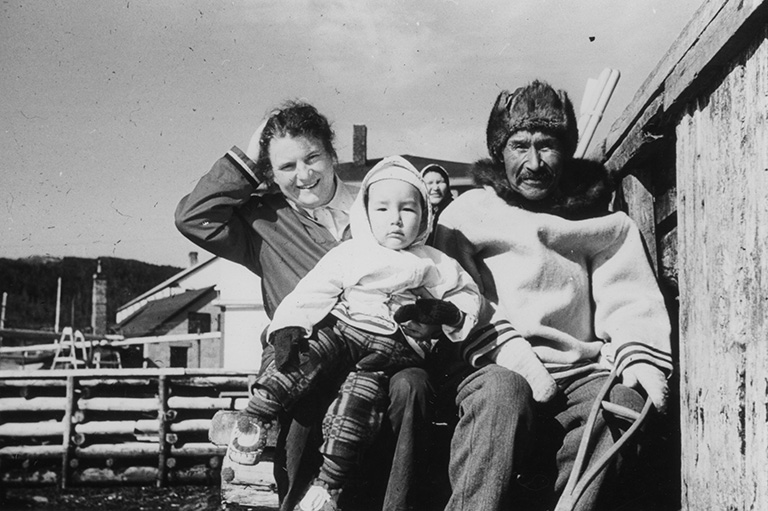

Vibert Douglas remained active well into retirement. A keen traveller, she attended conferences of the IFUW and International Union of Astronomers until a year before her death in 1988 at age ninety-three. She never tired of adventures in seeing the stars and used her retirement to chase eclipses all over the world. She carried her own luggage, rarely pre-booked hotel rooms, and made it a point to learn to say “to your good health” in several languages. She often took her nieces or nephews — and later her grand-nieces and grand-nephews — along to share these experiences.

Her niece Mary Douglas, by then a family doctor, recalled crossing the Khyber Pass between Pakistan and Afghanistan three times in one day with her — by bus, taxi, and lorry — because her visa was not in order. Her grand-nephew Dan Vibert Douglas laughed as he fondly recalled that, on a 1980 trip to India to view a solar eclipse, she brought with her a pair of glasses she had saved from a 1932 eclipse. Indeed, her frugality was legendary: She even made her own marmalade — in the Cambridge style of course, never the Oxford variety. Yet she was unfailingly generous to family, friends, colleagues, students, and war refugees, leaving a unique legacy as a scientist, humanitarian, internationalist, and feminist.

“In truth her head was in the stars,” said her friend and former student Shirley Brooks, “intimate with the heavenly bodies, familiar with galaxy after galaxy, but her feet were firmly planted on this earth with its stark reality.” After her death, a crater on the planet Venus was named after her, and Asteroid 3269 was renamed Vibert-Douglas in her honour.

Advertisement

Light Lines

Astrophysics is the study of astronomical objects, including the composition of stars and other heavenly bodies. While ancient astronomy focused on the position and motion of stars and planets — and was often driven by practical applications in surveying, navigation, timekeeping, and cartography — astrophysics built on this scientific knowledge with newer insights from physics and chemistry.

In the nineteenth century, scientists discovered that light from the sun or other stars, travelling through a prism, showed a multitude of dark-line regions where little or no light could be observed. Later, radiant lines were also found in solar spectra, which scientists began to capture on photographic plates. This was the beginning of the field of stellar spectroscopy.

Stars are burning balls of gas that release energy in the form of heat and light. The wavelengths of the light released depend on factors including the type of gas being burned and its temperature. Therefore, by studying stellar spectra, astrophysicists could begin to make inferences about the chemical composition — among other properties — of different stars.

By the late nineteenth century, increasingly sophisticated telescopes and photographic techniques fuelled further research, which led to the classification of stars into types and to the creation of star catalogues. Astronomers used the telescopes to make images of stars, while “computers” — who were almost always women — carefully analyzed the black-and-white images, performing complex mathematical calculations to determine the width and length of each absorption line. Developments in physics also fuelled interest in this field. For example, on an expedition to observe a solar eclipse in Brazil in 1919, Arthur Stanley Eddington showed that gravity bends the path of light when it passes near a massive star, thus corroborating Albert Einstein’s general relativity theory.

At Cambridge Observatory, Allie Vibert Douglas and Cecilia Payne were introduced as students to the analysis of stellar spectra — which not only provided clues as to the chemical composition but also to the velocity, temperature, density, and intrinsic luminosity of stars. Later, at Harvard College Observatory, Payne worked with computers who classified thousands of stars by comparing their spectra against that of known elements. Working for little pay or recognition, these computers none-the-less laid the foundation for a new field.

Vibert Douglas, on Eddington’s suggestion, applied spectral analysis to the statistical study of a certain large group of stars in order to determine the relation between stellar velocity — the speed and direction at which stars travel — and absolute magnitude — the brightness of those stars. Later, at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin, which was affiliated with the University of Chicago, she investigated the spectroscopic absolute magnitudes and parallaxes (a method of measuring a heavenly body’s distance from Earth using trigonometry) of approximately two hundred stars. While she mainly used the Yerkes collection of spectrum plates of stars, she also created a few plates of her own, which she kept to use as teaching aids later in her career. She continued her research on stellar spectroscopy in the 1930s while teaching at McGill University, where she collaborated with Canadian physicist John Stuart Foster on studies of the splitting of spectral lines of atoms and molecules due to the presence of an external electric field in solar atmospheres, a phenomenon known as the Stark effect. — Dianne Dodd

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement