Soldier Girl: The Emma Edmonds Story

-

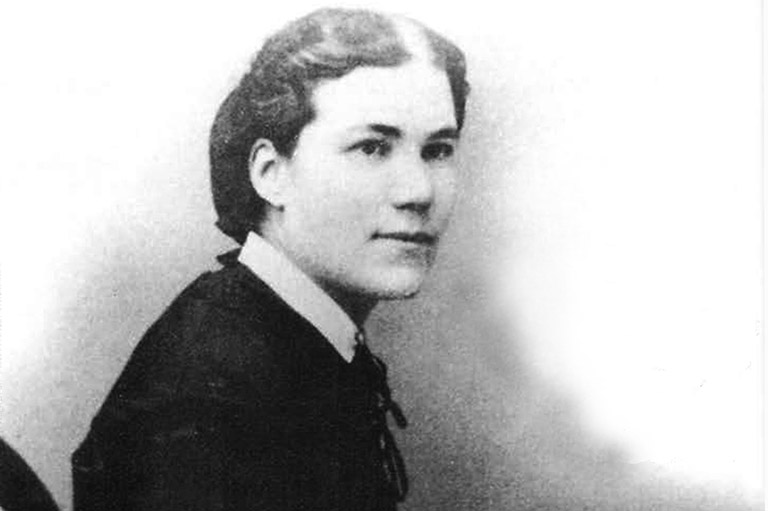

Faced with an abusive father and the certainty of an arranged marriage, Emma Edmonds fled her New Brunswick home at age fifteen and later assumed a masculine guise. She joined the Union Army when the Civil War broke out in 1861. Her true sex remained undetected until illness two years later forced her to end the charade.State Archives of Michigan / 02255

Faced with an abusive father and the certainty of an arranged marriage, Emma Edmonds fled her New Brunswick home at age fifteen and later assumed a masculine guise. She joined the Union Army when the Civil War broke out in 1861. Her true sex remained undetected until illness two years later forced her to end the charade.State Archives of Michigan / 02255 -

The stone church at Centreville, Virginia, where Emma tended wounded and dying soldiers after the Battle of Bull Run, July 1861.Collection of the New York Historical Society / 75139

The stone church at Centreville, Virginia, where Emma tended wounded and dying soldiers after the Battle of Bull Run, July 1861.Collection of the New York Historical Society / 75139 -

In male attire, Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonds sold Bibles in the northeastern United States under the name Frank Thompson prior to enlisting for the Civil War. Edmonds resumed her female identity in the middle of the war to undergo treatment for malaria, then worked as a nurse until war's end. In 1867, she married fellow New Brunswicker Linus Seelye and had three sons. They lived in various parts of the U.S. before finally settling in La Porte,Texas, where she died in 1898.Clarke Historical Library / Central Michigan University

In male attire, Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonds sold Bibles in the northeastern United States under the name Frank Thompson prior to enlisting for the Civil War. Edmonds resumed her female identity in the middle of the war to undergo treatment for malaria, then worked as a nurse until war's end. In 1867, she married fellow New Brunswicker Linus Seelye and had three sons. They lived in various parts of the U.S. before finally settling in La Porte,Texas, where she died in 1898.Clarke Historical Library / Central Michigan University -

On September 17, 1862, in the Battle of Antietam, 23,000 soldiers were killed or wounded—the bloodiest single-day battle in American history. The battle in Maryland, the first major Civil War engagement on Northern soil, halted Confederate general Robert E. Lee's bold invasion of the North and was a turning point in the four-year conflict.Collection of the New York Historical Society / 75140

On September 17, 1862, in the Battle of Antietam, 23,000 soldiers were killed or wounded—the bloodiest single-day battle in American history. The battle in Maryland, the first major Civil War engagement on Northern soil, halted Confederate general Robert E. Lee's bold invasion of the North and was a turning point in the four-year conflict.Collection of the New York Historical Society / 75140 -

According to her 1865 memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, from which this illustration is taken, Edmonds disguised herself as a black slave and passed into the Confederate camp.

According to her 1865 memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, from which this illustration is taken, Edmonds disguised herself as a black slave and passed into the Confederate camp. -

According to the Edmonds memoir, another cross-dressing soldier—before dying—told Emma that she had enlisted as a man to be nearer her only brother. To keep the secret, Edmonds agreed to bury the woman herself.

According to the Edmonds memoir, another cross-dressing soldier—before dying—told Emma that she had enlisted as a man to be nearer her only brother. To keep the secret, Edmonds agreed to bury the woman herself.

Would you even remotely consider impersonating and living as a member of the opposite sex—or as a member of a different race?

How about doing both at the same time, in a foreign land, in conditions of acute physical hardship, and with a likelihood of being maimed or meeting a violent at any moment?

New Brunswick-born Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonds did all of that.

Prior to and during the American Civil War, Canada served as a haven for escaped slaves, a base for Confederate covert operations, and a source of volunteers for both the Northern and Southern armies. An estimated 50,000 Canadians went south to fight, most of them intent upon ending the “peculiar institution”—slavery.

Emma was among them.

She was one of an estimated four hundred women who successfully disguised themselves as men and served in combat over the course of that bloody conflict, but her character and astonishing exploits separate her from all the rest. Her memoir Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, published in 1865, recounts the story of her remarkable life.

Born in 1841, baby Emma fell innocently afoul of her hard and uncompromising father who, in all matters, demanded immediate and complete submission from wife and children alike. Longing for a healthy son to make up for Emma’s epileptic older brother, he took instant and unforgiving umbrage at Emma’s arriving with the wrong credentials.

Growing up on the family farm in the rural settlement of Magaguadavic near Fredericton, New Brunswick, Emma developed into an accomplished rider, a crack shot, and a strong swimmer by her early teens. Energetic and adventurous, she sought out physical challenge and delighted in climbing to the tops of the tallest trees and buildings.

When she was nine years old, a peddler gave her a book about the adventures of Fanny Campbell, a teenage girl who disguised herself as a man and went sailing to find and free her sweetheart from the clutches of a ruthless band of pirates. Fanny’s exploits fired Emma’s imagination.

At fifteen, facing the unwelcome prospect of an arranged marriage to an older man, she ran away to live and work with a family friend, making ladies’ hats in the town of Salisbury. Within a year, she was co-owner of a millinery shop in Moncton.

Learning of her whereabouts, Emma’s father demanded that she return home, but Emma, perhaps inspired by Fanny Campbell, suddenly packed up, moved to Saint John, and there “disappeared” by assuming a male identity.

About her disguise, Emma later explained, “I think I was born into this world with some dormant antagonism toward men—my infant soul was impressed with a sense of my mother’s endured wrongs—and I probably drew from her breast with my daily food my love of independence and my hatred of male tyranny”

Cropping her fine, dark hair, tanning her face with stain, and donning a suit of men’s clothing, Emma strode out into the world as “Frank Thompson” and landed a job as an itinerant Bible salesman. Her Connecticut-based employer later claimed that of all the salesmen he’d hired over a period of thirty years, no one ever outsold Frank Thompson.

By the fall of 1860, Emma had made her way west to Flint, Michigan, where salesman Frank quickly gained a reputation as an upstanding young fellow. When the Civil War began April 12, 1861, twenty-year-old Emma was fired with loyalty toward her adopted country and went to Detroit to answer the call for volunteers.

The army’s perfunctory enlistment physicals rarely required recruits to strip down. So long as an aspiring bit of cannon fodder wasn’t blind, lame, missing limbs, or subject to fits, bounty-paid recruiters were happy to speed them into a uniform.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

At first, five-foot, six-inch Frank Thompson was turned away for being shy of the army’s height standard. However, to advance President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops, the standard was lowered a couple of weeks later, and Emma tried again. Her physical consisted of little more than answering a few questions and demonstrating a firm handshake. On May 25, 1861, Emma proudly emerged onto the streets of Detroit as Private Frank Thompson, Company F, Second Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Like most rural women of her time, Emma was physically strong, used to the outdoors, and—unlike her city-bred fellow recruits—handy with firearms and at home with horses and mules.

With her regiment filled with hundreds of smooth-faced boys in loose, poorly fitted uniforms, Emma gained easy acceptance as Private Frank Thompson. The prevailing standards of male modesty and hygiene helped her. too. Sleeping fully clothed and bathing in undergarments were common among Civil War soldiers in the field. Shunning the foul-smelling, open-trench pits that passed for latrines, many sought the privacy of nearby woods and freshwater streams to attend to their personal needs. Emma attracted no notice by doing likewise.

When basic training was completed, she was assigned to duty as a male nurse and postman for her brigade.

On July 15, 1861, the Second Michigan was ordered to Bull Run, a stream near the vital railhead at Manassas Junction, Virginia, where Confederate troops were known to be converging.

Six days later, Emma was initiated into the realities of war. Standing shoulder to shoulder in the blue ranks, she withstood the trauma of howling artillery shells slicing bloody lanes through compact masses of men, tossing body parts, viscera, and broken weapons and equipment high in the air.

The battle, which had begun at six in the morning, turned into a disastrous rout for the Union by four in the afternoon, and Emma found herself pushing through the wreck of the retreating army. At a stone church that had been converted into an emergency field hospital, she encountered fly-ridden heaps of amputated limbs, mutilated flesh, and dead bodies, and volunteered to tend wounded and dying soldiers.

Later she wrote that she had “gone to the war with no other ambition than to nurse the sick and care for the wounded. I had inherited from my mother a rare gift of nursing, and when not too weary or exhausted, there was a magnetic power in my hands to soothe the delirium.”

In the days following the battle, the beaten remnants of the Union army straggled into Washington. With victorious Southern flags fluttering within easy sight, citizens feared imminent invasion and government authorities contemplated evacuation.

Arriving in the beleaguered city in search of her comrades, Emma visited temporary hospitals, gave care to friends and strangers alike, and penned letters for the many too weak to do it for themselves. She wrote that “that extraordinary march from Bull Run, through rain, mud and chagrin, did more toward filling the hospitals than did the battle itself. There are great strong men dying all around me, and while I write, there are three being carried past the window to the dead room.”

Within weeks of the disastrous battle, President Lincoln appointed a new military commander, General George B. McClellan, who began whipping the disorganized mobs of soldiers into an army again. As the Northern divisions regained their warlike spirit, Emma found a new confidence. She was appointed postmaster of her brigade and she routinely galloped forty kilometres a day to pick up and deliver bags of letters and packages. It was dangerous work, and on one occasion she rode through papers strewn over the very ground where a fellow postman had been ambushed and shot the day before.

Emma successfully soldiered through the great Virginia campaigns of 1862, including the bloodbaths at the battles of Second Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Antietam, where the Union regiments were savagely raked and winnowed.

When a Union agent was hanged for spying, she volunteered to take his place. Though interviewed by a panel of high-ranking officers for the dangerous work, she still managed to conceal her true sex. Ever resourceful, she shaved her head, blackened her skin with silver nitrate, donned a plantation suit and a curly black wig, and passed into the Confederate camp at Yorktown as a slave answering to the name “Cuff.”

Mingling with a gang of black labourers, she hauled wheelbarrows of gravel to workers atop an eight-foot wall. The hot, sweaty work caused the silver nitrate to begin to fade. At one point, a slave pointed at Emma and exclaimed, “Durned if’n that feller ain’t turnin’ white.” Quick-witted Emma countered, “I’ve always expected to come white, my mother’s a white woman.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

After a day of manhandling heavy loads of gravel, Emmas wrists and hands were horribly blistered, but she saved herself by talking another slave into changing jobs with her. For the next two days Emma moved about the camp as a water bearer, all the time watching, listening, and even managing to make rough sketches of the enemy fortifications.

Overhearing someone loudly haranguing a group of soldiers in a familiar voice, she recognized the speaker as a peddler who visited the Union lines once a week to sell newspapers and stationery. He was describing the Northern camp in detail, using a map displaying its layout and troop dispositions. “He was a fated man from that moment,” Emma later remembered. “His life was not worth three cents.”

During the night of the third day, she was surprised to be handed a musket and told to take a position on the picket line. When an opportune moment arrived. Cuff slipped away in the darkness and, rebel musket in hand, made a safe return to her own headquarters. Assisted by the information provided by Emma, General McClellan bombarded the Confederate fortifications with such accuracy that the rebels were soon forced to abandon them.

On other occasions, Emma slipped across enemy lines as an Irish immigrant woman and as a black female slave. In the latter guise, complete with calico bandana, she once ended up cooking rations at Confederate headquarters, within watching distance of Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee.

At the bloody Battle of Antietam, Emma came across a young soldier, severely wounded in the neck and near death. As she gave him comfort, the youth confided that he was actually a female, enlisted as a man to be near her only brother, who had been killed earlier in the day. To protect the secret according to the youth’s dying wish, Emma buried her nearby, “without coffin or shroud, only a blanket for a winding sheet” With poetry, she gave expression to the heart-rending experience:

Her race is run. In southern clime, She rests among the brave;

Where perfumed blossoms gently fall, Like tears, around her grave.

No loving friends are near to weep, Or plant bright flowers there;

But hirdlings chant a requiem sweet, And strangers breathe a prayer.

She sleeps in peace; yes sweetly sleeps. Her sorrows are all o’er;

With her the storms of life are past: She’s found the heavenly shore.

On March 20, 1863, Emma was transferred to Louisville, Kentucky. Disguised as a young Kentucky lad, she went spying again. Arriving at an outlying village, she found a wedding in progress. The bridegroom was a captain of rebel cavalry on the lookout for likely recruits. Stopping to ask for a bite to eat, Emma was noticed by the captain and found herself conscripted into a unit of mounted rebel troops.

Next day, outfitted as a Confederate trooper, she rode out to engage the Yankees. “I did not despair,” Emma later wrote, “but trusted in Providence and my own ingenuity to escape from this dilemma.”

Encountering a detachment of Union cavalry, a fight broke out. In the melee, Emma contrived for her horse to become unmanageable and appear to accidentally send her across Union lines. Luckily, once across, she was recognized and protected.

Returning to the fight, Emma was spotted by the captain who had forced her into rebel service. Enraged and determined to skewer her on the point of his sabre, he charged, only to receive the contents of Emma’s pistol in his face. “This act made me the center of attention,” Emma recalled. “Every rebel seemed determined to have the pleasure of killing me first. I escaped without receiving a scratch, but my horse was badly cut across the neck with a sabre.”

Although commended for her performance, Emma was barred from spying in the area again lest she be recognized and hanged from the nearest tree. She observed, “Not having any particular fancy for such an exalted position, I turned my attention to more quiet and less dangerous duties.”

However, Emma had one more mission to perform before retiring from espionage—to help break up a Confederate spy ring operating out of Union-occupied Louisville. Passing herself off as “Charles Mayberry,” she got herself a menial job with a local merchant of rabidly outspoken southern views.

Over a number of weeks, Emma gained the merchant’s trust and feigned an interest in enlisting in the Confederate service. The merchant obligingly introduced her to a Confederate agent who in turn told her about a sutler spying for the South while selling supplies to Union soldiers, and about a second southern agent who came and went as a photographer selling pictures to Union generals.

With Emma’s information, the Louisville spy ring was duly put out of business. Later, in 1863, while posted to a military hospital near Vicksburg, Mississippi, Emma contracted malaria. Unable to admit herself for treatment for fear of betraying her true sex, she travelled to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where she put on a dress and checked into a hospital.

Cured and on her way back to her unit a few weeks later, Emma was shocked to come across an army bulletin posted in the window of a newspaper office that listed her nom de guerre, Frank Thompson, as a deserter. The offence was punishable by death.

With her military career finished, Emma used the last of her funds to go by train to Washington where, as Sarah Edmonds, she worked as a nurse for the United States Christian Sanitary Commission until the end of the war. In 1865, Emma recorded her civil war experiences in a memoir titled Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps and Battlefields. It became a bestseller, and Emma donated all of her royalty earnings to the U.S. War Relief Fund.

Homesick for Canada, she returned for a visit, accompanied by Linus Seelye, a fellow New Brunswicker whom she’d met and fallen in love with while nursing in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, in 1864. She and Linus were married in 1867 and raised three sons, one of whom enlisted in the U.S. Army “just like Mama did.”

In 1883, Emma visited Flint, Michigan, and looked up an old army pal, Damon Stewart. Finding him behind a desk in his dry goods store, Emma asked if he might know the present whereabouts of Frank Thompson.

Damon asked, “Are you his mother?”

“No, I’m not his mother,” Emma answered.

“His sister, perhaps?” Damon ventured.

Emma took a pencil from Damon’s hand and wrote, “Be quiet. I am Frank Thompson!”

“What did I do next?” Damon later recalled to a Flint newspaper reporter. “Sat down. I think, wilted.” Of Emma, he said, “She was as tranquil and self-possessed as ever my little friend Frank had been.”

When questioned about ever having suspected Frank Thompson’s real sex, Damon answered, “Never! We jested about the ridiculous little boots and called Frank our ‘little woman,’ but he took it all in good part.”

Carrying the brand of deserter had never settled well with Emma. On her behalf, Damon contacted other men of the old Second Michigan, told them that Frank Thompson had turned up, and that Frank was a woman named Emma Seelye. He asked them to join a writing campaign to seek recognition of Emma’s war service. With the added support of former officers and other prominent men who’d known and served with her, a sizable petition was assembled and submitted to the U.S. War Department.

By a special act of the Congress, passed on July 5, 1884, Emma Edmonds was granted an honourable discharge from the United States Army “for her sacrifice in the line of duty, her splendid record as a soldier, her unblemished character, and disabilities incurred in the service.” She also received a modest cash bonus and a veteran’s pension of twelve dollars a month.

After residing in various U.S. states, Emma and Linus finally settled in La Porte, Texas. There, by virtue of her discharge and veteran’s pension, she was duly accepted as a full member of the Grand Army of the Republic, the Union army veterans’ organization. She is the only woman ever to be so honoured.

Her last years were plagued with illness—attributed to the extreme conditions and exertions of her war years. They were also difficult financially; sometimes she was nearly destitute.

On the morning of September 5, 1898, Emma’s dog, Jack, barked an alarm. Emma had succumbed to a stroke. First buried at La Porte, Emma’s remains were disinterred and conveyed to nearby Houston in 1901. There, amid the rhythmic Memorial Day thump of muffled drums, she was buried in the military section of Washington Cemetery—the only female permitted eternal rest in the Civil War veterans’ plot.

In 1988, Emma’s courage, daring, and contribution to the Union’s espionage and military fronts were honoured by her induction into both the United States Military Intelligence Hall of Fame and the State of Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame. In her own country, she was elected to New Brunswick’s Hall of Fame in 1990.

Although devoted to the cause of her adopted country; Emma always remained a Canadian—heart and soul. Enjoying an off-duty tour of the Senate chamber while on furlough in Washington during the summer of 1862, her memoir records that she came upon two paintings depicting respectively the surrenders of Lord Cornwallis and General Burgoyne to American forces during the Revolutionary War.

Her Canadian blood ran hot as she took in the portrayals of Britannia in defeat. “I felt a warm current of blood rush to my face as I contemplated the humiliating scene—the spirit of Johnny Bull triumphed over my Yankee predilections—and I left the building with feelings of humiliation and disgust.”

Today, one can easily pass through the older section of Houston’s Washington Cemetery and pause to admire a certain beautiful oak tree without noticing the small, weathered marker that lies close beneath it. The eroded letters, barely traceable across the pitted, limestone surface, herald the life of a heroic Canadian who helped preserve the United States and free a people from slavery’: Emma E. Seelye, Army Nurse.

Women Soldiers in the Civil War

Why did so many women, up to 250 in the Confederate armies and 400 in the Union, disguise themselves as men to fight in the American Civil War?

Women played prominent roles during the war as nurses, cooks, laundresses, and camp followers. Sometimes they even found it necessary to take up arms and defend themselves when caught in the thick of fighting. All of these roles were accepted, even honoured, by the soldiers and the public.

The case was different for those women who disguised themselves as men in order to fight. If discovered at all, they were discharged and presumed to be of questionable moral character. Their bravery in battle was often forgotten in favour of the sensational story of their cross-dressing. These women were viewed as aberrations, and yet it is speculated that hundreds served in the war this way. Clearly this phenomenon was not so isolated as is generally assumed.

The image of the woman warrior is not uncommon. Many precedents appear in the myths and histories of various cultures throughout time. Though the Amazons and Joan of Arc are most well known, others exist. Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine led a force of women dressed as men, armed and on horseback, in the Second Crusade of the twelfth century. In the eighteenth century a British woman, Mary Read, disguised as a man, served in the infantry and the cavalry in the War of the Spanish Succession before becoming a pirate. Deborah Sampson, Margaret Corbin, and Nancy Hart all fought in the American Revolution.

Cross-dressing women warriors also existed in the literature of the era. Maturin Murray Ballou’s Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain was published in 1845. The Female Volunteer, published 1851, detailed the exploits of a woman who fought in the Mexican War. During the Civil War, novels such as The Lady Lieutenant: The Strange and Thrilling Adventures of Madeline Moore and Dora, The American Amazon were popular.

Though many women joined the war effort disguised as men for the love of a man, the love of adventure, or the love of country, historian Elizabeth Leonard speculates a fourth motivation: money. Records indicate that a large portion of Civil War women were from less affluent backgrounds and may have appreciated the opportunities afforded by fighting the war as men. Immigrants, working-class women, and farm girls—women accustomed to hard work—were more apt to sign up to fight than middle-class women, who opted more often to become nurses.

Why did so many women choose to fight in the Civil War? For the same reasons as the men—adventure, patriotism, a sense of duty. Some women followed lovers or husbands or brothers; some wanted to escape oppressive and confining domestic situations and better their circumstances, both socially and financially.

Both Union and Confederate armies became increasingly desperate for volunteers as the war progressed, and it is conceivable that some soldiers chose to turn a blind eye to their effeminate comrades. The simple act of cutting their hair short and donning pants gave these women a freedom they had never known, a freedom they had only imagined.

— Sarah Burton

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!