Headstrong Heiress

Kathleen Dunsmuir’s sleeve warm bun to the bigger, dirtier man’s hand through the canteen window. She had already passed a mug of hot chocolate (handle out) to the same man and smiled at him when he thanked her. And on to the next soldier. It was February 1915, and Kathleen — a daughter of British Columbia’s wealthy Dunsmuir family — was on the quay in Le Havre, France, serving food from a van that she and a friend had outfitted to provide comfort to soldiers in the First World War.

While no full-length biography of Kathleen Euphemia Dunsmuir has yet been written, hers is one of the most compelling untold stories of several generations of Dunsmuir women. She was born into great wealth and privilege in a colonial society bubble in Victoria and even spent part of her youth living in Hatley Castle, the second of two castles — along with Craigdarroch — built by the Dunsmuirs. She showed a great generosity of spirit and an embrace of hard work in supporting the troops during the first and second world wars; yet that selflessness was juxtaposed with her desire to be a Depression-era movie star and her willingness to pay for the chance — ultimately leading to her financial ruin.

Born on December 22, 1891, Kathleen was the tenth of James and Laura Dunsmuir’s twelve children and the eighth of nine girls (one son, Alexander Lee, died in infancy). Her grandfather, Robert Dunsmuir, was a self-made millionaire: From a family of Ayrshire coalmasters, he immigrated to Vancouver Island from Scotland in 1851 on a three-year contract as a coal miner for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

After his contract was completed, he discovered a rich coal seam on the island, developed it through his own mining claim, and eventually became wealthy through hard work, shrewd investments, and ruthless employment practices. It’s said that Robert had enticed his wife, Joan, to come with him to British Columbia by promising to build her a castle. It may be an apocryphal story; nevertheless Robert built Craigdarroch for Joan on a hill that overlooked Victoria. He didn’t live to see completion of his “bonanza castle,” as supersized mansions built to show off wealth were once known. Robert died in 1889 of renal failure. Joan lived at Craigdarroch from its completion in 1890 to her death in 1908.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Their eldest son, James — Kathleen’s father — had been born mere days after Robert and Joan landed at the Hudson’s Bay Company outpost of Fort Vancouver in 1851 following the six-month ocean voyage from Scotland. James and his brother Alexander, born in 1853, followed Robert into the family business.

After studying mining engineering in the southern United States, where he wooed and wed Laura Miller Surles, James became a manager in his father’s coal company. By the late 1800s, R. Dunsmuir & Sons had grown into an empire with mining, shipping, a quarry, real estate, railway interests, and an iron foundry, and the Dunsmuirs were the richest family in the province — although also despised in some quarters for their ruthless clampdowns on labour strikes. James Dunsmuir served as the premier of British Columbia from 1900 to 1902 and as Lieutenant-Governor from 1906 to 1909. The “Dunsmuir kids” (the nickname given to the four younger daughters, born over a span of just four years) and their older sisters were at the centre of a glittering social milieu for Victoria’s wealthy and privileged, coming out to society while their father was Lieutenant-Governor. The first Dunsmuir era ball at Government House in 1906 was described in great detail in society columns, which noted that their mother Laura’s necklace, earrings, and tiara featured “magnificent diamonds of the first water” and that their sister-in-law Maude wore “a dazzling gown of goblin green net over silk of the same hue with a jaunty feather in her hair.”

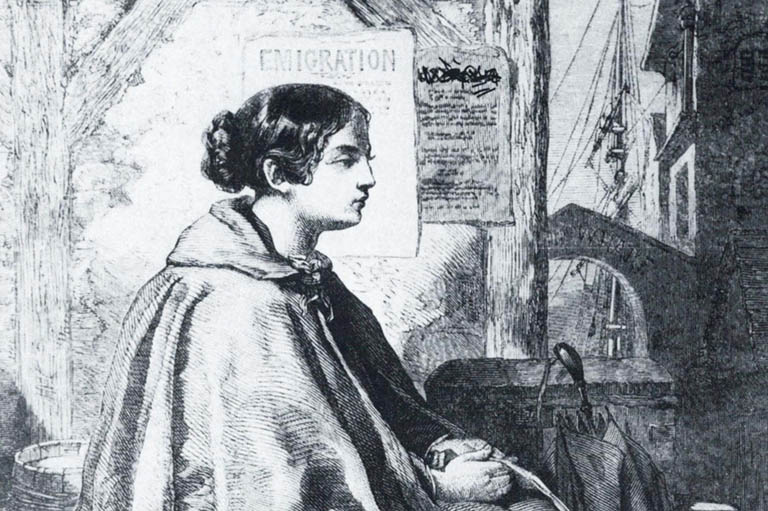

Kathleen was often referred to as the prettiest of all the daughters; photos of the day show a finely featured young woman with blonde hair that was thick and wavy, tumbling to her shoulders in curls when she was a smiling little girl. She wore a big, beautiful hat when she was a flower girl at the 1901 wedding of her sister Sarah Byrd (nicknamed Byrdie) to Guy Audain and appeared in elaborate costume with three of her sisters in a photo taken around the turn of the twentieth century.

Advertisement

When the First World War started in July 1914, Kathleen initially did her bit with her sisters in Victoria, raising money and morale by performing at local venues such as the Royal Theatre. The Vancouver Province reported in November 1914 that she and her older sister Jessie Muriel, nicknamed Moulie, would perform in a “futuristic song and dance” at the Avenue Theatre in Vancouver — foreshadowing Kathleen’s later dreams of theatrical stardom.

By Christmas of that year, Kathleen (known as Kat in the family) and Moulie were in London visiting their older sister Elizabeth Maude (nicknamed Bessie). By February 1915 Kathleen, then twenty-four years old, was across the English Channel on the quay in Le Havre, serving hot chocolate and buns to servicemen from the mobile canteen that she had set up with the help of a friend from Victoria, Kay Scott. Their venture was chaperoned by Scott’s mother.

Kathleen wrote letters, cards, and cables regularly, letting her family back home know she was fine and looking for money. While she had an allowance, it wasn’t unlimited. “I am writing to see if you can possibly get $2,500,” Kathleen wrote to her mother in April 1915. “We still have some money left, but we give so much. ... We give two big buns for a penny, instead of one. Even then we might do alright, but we feed all the men who have nothing [for] free, as well as trains of wounded … we also give everything free to the guards who bring in the German prisoners, so you see we do need a lot. How they do love on a cold morning at 5 or 6 o’clock to have hot chocolate and buns! … Do try to get the money and don’t think that it will be squandered, for every cent that is left after the war will go towards buying cork legs and other things for the wounded.”

The French port of Le Havre was the primary disembarkation point for the Canadian and British expeditionary forces in the First World War. The first Canadian troops to land in France in December 1914 were the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (the Princess Pats). By February 1915, Canadian troops were in Belgium and France. They fought in the Second Battle of Ypres in April and May 1915. Myriad young men passed by Kathleen’s canteen.

“I almost choke with misery when I see the trains of wounded come down.”

On May 7, 1915, the Victoria Daily Colonist published extracts of some letters Kathleen had written to her mother. “I almost choke with misery when the trains of wounded come down,” one letter reads. “The poor things try to be cheerful … we talk to them and as they love to hear English, I feel I am doing some good. My heart sinks when I see thousands of men rushing and clamoring for food … the men love our place and we give them big slices of bread and good tea. We fed a long train-full of wounded yesterday, and as they had no food, they were very glad to get what we gave them.”

In retrospect, the May 7 publication date was unsettling, since it was on that same day that a German U-boat sank the British ocean liner Lusitania, killing almost 1,200 passengers and crew. Kathleen’s brother James, known to the family as Boy, was aboard. Waiting impatiently for his unit to go overseas, James had decided to sail to England at his own expense and join a regiment there. His remains were never found, and the Dunsmuir family never recovered from his loss.

When James’s unit, the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles Battalion, finally arrived, an officer wrote to his family: “Who do you think we met almost immediately on arriving in France? Why, Kathleen Dunsmuir of course! ... After the men had all had their tea in big generous mugs … [they] gave three hearty cheers for Jimmie’s brave sister.”

It wasn’t long until Kathleen turned the head of Major Arthur Selden Humphreys, who, as deputy assistant quartermaster at Le Havre, had helped her with the canteen. In wartime, marriage proposals were frequent, and engagements were usually short; Kathleen and Arthur were married in London, England, on October 20, 1915.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Kathleen and her husband returned to Victoria after the war, and Humphreys, who might have expected the leisurely life of a husband with a monied spouse, instead was tapped to be aide-de-camp to British Columbia’s Lieutenant-Governor. This suited Kathleen, who was known to say, “You know how I hate sluggards!” as she became a hostess extraordinaire at the Humphreys’ Victoria home. Known as Westover, it was formerly a coach house of the Leasowes estate, built in 1904. The mansion, near Government House, had been purchased in 1911 by her parents as a pied-à-terre in Victoria; when Kathleen lived there, it was a social hub in the provincial capital of the Roaring Twenties. Kathleen’s nephew, Jimmy Audain, remembers how his aunt “kept open house at Westover. People knew how lavish she was in her entertainment and trespassed greatly on her generosity and good nature.” Once, on a whim, she greeted guests in a bright green wig. Her parties were rumoured to have bordered on bacchanalian.

The couple had four children: James, Joan, Jill, and Judith. But by 1930, unfortunately, the marriage was over. Like other disappointing spouses dumped by Dunsmuir daughters, Humphreys was persuaded to accept a generous payoff. The Dunsmuir family sent him to China with an allowance and some money to start a business. Meanwhile, Kathleen turned her attention to the theatrical career she felt she had abandoned to serve during the war.

At the age of forty, she prepared a photo portfolio and rented a place in Beverly Hills, California, where she made frequent trips accompanied by her daughters, then aged twelve, seven, and four. While the beauty of her youth may have faded some, she used her experience entertaining and invited studio executives to dine with her as she looked for her big break. She was wealthy enough to make it purely transactional, implying that she might invest in a film if it included a role for her.

Kathleen found her opportunity closer to home when she met the film producer and promoter — some would say hustler — Kenneth J. Bishop. Bishop had a scheme to produce cheap, made-in-Canada flicks for distribution to the United Kingdom, taking advantage of a law that required British cinemas to show a certain percentage of films “of British character.”

It wasn’t long before Kathleen gave Bishop’s Commonwealth Productions $10,000 ($225,000 in today’s dollars) to back a film called The Crimson Paradise, with herself cast in a supporting role. The film was shot on Vancouver Island, at Hatley Castle — a grand sandstone-trimmed edifice where her widowed mother still lived — and on Dunsmuir property elsewhere. In addition to acting, Kathleen provided what we would today call craft services, feeding cast and crew; and she entreated friends and family members to take unpaid bit parts in the film. Bishop wheedled another $20,000 (about $450,000 today) out of her.

“Miss Dunsmuir made a charming supporting lead and played her role admirably.”

When the film was finished after just ten weeks of shooting, the only way it could be shown in Victoria — because of U.S. control of film distribution — was at late-night screenings at the Capitol Theatre.

The Daily Colonist gave front-page coverage to the 11:00 p.m. premiere of “Canada’s First All-Talking Motion Picture” at the floodlit Capitol on December 14, 1933. In addition to ads for the film itself, there were also ads telling people where the cast would be dining, if anyone wanted to meet them. Alas, reviews damned the film with the faintest of praise for Kathleen: “Miss Dunsmuir made a charming supporting lead and portrayed her role admirably.”

Advertisement

Kathleen’s film adventure bankrupted her, and she ended up moving into rooms above the former stables at Hatley until she could persuade her mother to finance her next move. Laura Dunsmuir died in the summer of 1937, leaving trustees in charge of her estate with instructions to dole out the proceeds from the sale of her assets in nine equal portions to her seven remaining daughters, her son Robin’s widow, Maude, and the children of her deceased daughter, Byrdie.

By October of that year, Kathleen and her three daughters were in Switzerland; they then moved to London shortly before the start of the Second World War. When the war broke out, Kathleen reprised her mobile canteen efforts, this time organizing and paying for one at Aldershot, a major British military base about fifty kilometres southwest of London. She also volunteered her time at the canteen at British Columbia House, the province’s foothold in England, on London’s Regent Street. Kathleen’s eldest daughter, Joan, twenty-one, worked at the canteen and then enlisted in the Women’s Transport Service (FANY), where women worked as drivers and mechanics for ambulances and other military vehicles as well as serving in other roles in the war. Her second daughter, fifteen-year-old Jill, couldn’t wait to be old enough to help out, while the youngest, twelve-year-old Judy, was at school in Wales

. While Kathleen was in London, her twenty-three-year-old son, James Selden Humphreys, a flying officer with the RAF Transport Command, got married. They decided to celebrate with a night out at the Café de Paris nightclub on Saturday March 8, 1941 — in the midst of the Blitz.

Patrons crowded the floor to dance to the Andrews Sisters’ horn-heavy hit “Oh Johnny! Oh, Johnny, Oh!” The party sipped champagne to celebrate. And then a bomb came down an air ventilation shaft into the club a little before 10:00 p.m. — and exploded. The carnage brought on by the fifty-kilogram bomb was horrific: Musicians decapitated; diners killed instantly as the blast in the confined underground space exploded their lungs. Sheet music fluttered to the ground amid the smoke, the screams, the flames, and the fumes.

Jim and his wife were among the scores injured. Kathleen was killed. Her ashes were shipped home and interred in the Dunsmuir family plot in Victoria’s Ross Bay cemetery. The monument that marks where she’s buried with her sister Elinor notes that she was “killed by enemy action in London March 8th 1941 Rest in Peace.”

Kathleen’s modest epitaph stands in contrast to her larger-than-life personality. In the end, her grandiose gestures — both selfless and self-serving — cost her most of her inherited fortune. She wasn’t alone in that. So many of her siblings and cousins frittered away their inheritance that the family fortune created by her grandfather Robert was pretty much gone within three generations.

Still, the family bequeathed us two stunning examples of built heritage: Hatley Castle, now a National Historic Site and the administrative centre of Royal Roads University, and Craigdarroch Castle, also a National Historic Site and a repository of much Dunsmuir lore. The descendants also left a legacy of quirky stories, many of them revolving around the heiress whose personality remains a conundrum — Kathleen Euphemia Dunsmuir.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement