Harriet Tubman's Canadian Legacy

Freedom seeker Joe Bailey, terrified by the slave catchers not far behind him and the roiling waters below, couldn’t take his eyes off his feet as he crossed the suspension bridge high above the Niagara River. “Joe, come look at the falls! Joe, you fool you, come see the falls! It’s your last chance,” the small woman up ahead of him on the bridge chided, pointing to the majestic Horseshoe Falls thundering in the distance to the left of them.

When Bailey finally stepped off the bridge onto Canadian soil, he sang for joy and shouted that his next trip would be to heaven. His guide didn’t let up. “You might have looked at the falls first, and then gone to heaven afterwards.”

The woman in charge that November day in 1856 was Harriet Tubman, perhaps the greatest conductor on the Underground Railroad, a network of safe houses and routes for Black freedom seekers that led from the slave states of the American South to safety in Canada. A plaque near the former site of the Niagara suspension bridge memorializes the moment she led Joe Bailey to freedom, but he was far from her only passenger on the Underground Railroad. For the better part of a decade, she lived in St. Catharines, in the Niagara region of present-day Ontario, while journeying into danger again and again to free other enslaved people and guide them to a new life. This indomitable woman who couldn’t read or write was a towering force for justice — a shining light amidst the evil gloom of American slavery.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Ross in Maryland around 1822 to enslaved parents Ben Ross and Harriet “Rit” Green. (She later adopted her mother’s first name as her own.) When she was a teenager, an overseer threw a heavy object that hit her in the head. The injury nearly killed her; for the rest of her life she suffered bouts of intense lethargy and unconsciousness as well as visions that she interpreted as a source of inspiration. At about the age of twenty-two, she married a free Black man, John Tubman, but the marriage didn’t change her status. Any children born to the Tubmans would also have been enslaved.

The fifth of nine children, Tubman saw little of her father, Ben, a well-respected timber inspector whose owner released him from slavery in 1840. She spent more time with her mother, Rit, and her brothers and sisters in a close and loving family. Under slavery, such families could be ripped apart at any moment, as when Harriet’s sister and niece — some accounts say it was two or even three sisters — were sold away in the summer of 1849. The realization that she could share their fate pushed Harriet into her first escape attempt that September, along with two of her brothers, Ben and Henry.

The attempt failed. Later that year Tubman tried again — this time alone — and followed the North Star to freedom in Philadelphia. Although she quickly made connections to northern abolitionists and operatives on the Underground Railroad, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 by the U.S. Congress meant that she was no longer safe on American soil: Her former slave master could hunt her down and capture her, even in the free states. So Tubman looked farther north. In 1851, she crossed the Niagara gorge and moved to St. Catharines, in what was then the British colony of Canada West (also called Upper Canada).

Tubman is a familiar figure in American history, but the years she spent in the Niagara region are less well-known. Viewers of the 2019 biopic Harriet might have been surprised by the scene depicting Tubman’s new home in freedom, with the place name “St. Catharines” superimposed over a chilly-looking collection of plain wooden houses. “It was her base of operations. This is where she plotted out her rescue missions,” said Rochelle Bush, owner of Tubman Tours and historian of the Salem Chapel British Methodist Episcopal Church in St. Catharines, where Tubman once worshipped. “Everybody knows the story. They just don’t know that it happened in Canada.”

Advertisement

“Part of her courage was rooted in her profound love for her family,” said Kate Clifford Larson, author of Bound for the Promised Land and an adviser on the movie Harriet. “That’s why she kept going back for her family and friends — she couldn’t be happy without them. Her parents struggled to keep the family together and keep them alive, and she repaid them by returning again and again to help them.”

In 1855, Tubman rescued three brothers and a sister-in-law. In 1857, she returned to rescue her parents. Because she left no journals or letters, there’s no record of exactly how Tubman managed to find her way to safety again and again. Without the help of a map, a compass, or written instructions — but with an intimate knowledge of Delaware’s waterways and a gift for quick, creative thinking — she navigated rivers, walked tremendous distances through swamps and forests, and somehow kept frightened people of all ages safe. “She couldn’t read or write, but she had the ability to read the night sky,” Larson said. “She could read the forest. She could read the fields. She could read the marshes and the water. She could use all of her senses to tell her what she needed to know.”

Tubman was a deeply religious person who drew strength and determination from her belief that she had been called to free the enslaved and to help end enslavement. She believed that she received divine guidance during the epileptic spells resulting from her early brain injury. She used hymns to convey her plans, since enslaved people understood that there was a second meaning behind what she was singing: “Steal Away to Jesus” or “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” would signal that it was time to start an escape. As she once proudly declared, she “never lost a passenger.” All of the freedom seekers who followed her settled in St. Catharines at first; many took new names as free people and moved to other areas of what is now southwestern Ontario.

One person Harriet Tubman didn’t bring to Canada was her husband. She saved up to buy John Tubman new clothes, but when she returned to Maryland in the fall of 1851 to rescue him, she discovered he’d married a free woman and wasn’t interested in leaving. She simply gathered others and took them back to Canada with her. Although John is sometimes criticized, his status as a free man would have meant nothing to the slave catchers had he been taken while accompanying Harriet. Captured runaways were frequently whipped, shackled, and even branded. If seen as too much trouble, they could be sold “down the river” to harsher plantations in the Deep South.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

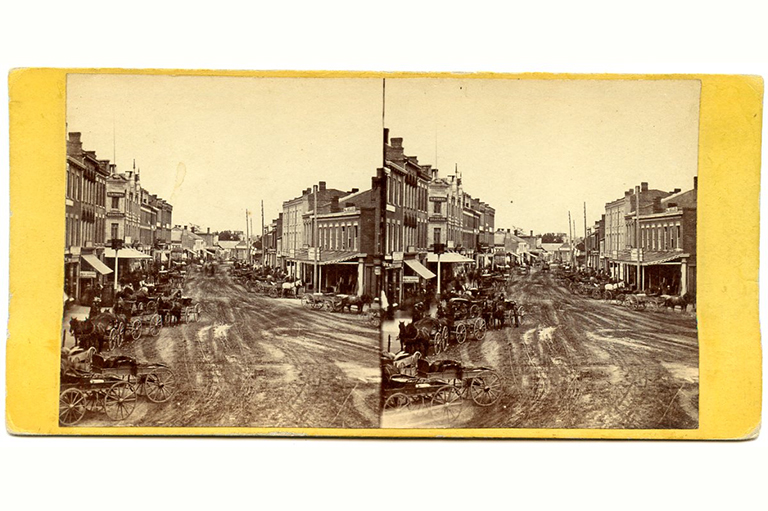

At the time Tubman arrived in Canada, there was already a tightly knit Black community in St. Catharines centred around the Salem Chapel at Geneva and North streets. Black people had lived in St. Catharines since the late 1700s, and by the mid-1800s Black residents accounted for about fifteen per cent of the population.

Details of Tubman’s life in Canada are scant, but it’s known that she cooked and cleaned to earn money, and the city paid her a small stipend to take in orphans. She rented a boarding house on North Street, where she likely provided rooms to freedom seekers. Indeed, there is something astonishing in the ordinariness of seeing the name “Harriet Tubbman” listed in the 1858 assessment rolls in the city’s St. Paul Ward.

Life in St. Catharines, and in other Canadian destinations for the Underground Railroad such as Windsor and Chatham, wasn’t easy. Nor did freedom seekers escape racist discrimination, whether formalized or simply embedded in everyday life. Legislation in Canada West (and later Ontario) supported the existence of racially segregated schools, and, although Black residents theoretically had the legal right to send their children to public schools along with all other citizens, social pressure and the power of prejudiced school board trustees in many cases forced the establishment of separate, often underfunded, schools for Black children. Black residents tended to live in the same areas in observance of an unwritten but nonetheless rigid form of segregation. They were, however, able to live freely, earn a living, and build a life of dignity.

Indeed, for Bush and many others in St. Catharines, the freedom seekers are part of their personal heritage. Bush said her mother heard first-hand stories about enslavement and freedom from her grandparents. “My mother was only two generations removed from slavery.”

Nurtured by this free Black community, Tubman in turn gave her all to it and to the larger cause of abolition. “The anti-slavery cause was in full force here,” said Bush. “What St. Catharines meant for her was being in a powerful position where she could effect change.” Some of the people Tubman worked with in St. Catharines were Black people who had escaped slavery, while others were white abolitionists such as Rev. Hiram Wilson, an American missionary who moved to Canada to assist freedom seekers in both body and soul; William Hamilton Merritt, a prominent former military leader turned businessman and politician who started helping fugitive slaves in the 1840s; and Rev. Michael Willis, a Presbyterian minister in Toronto who insisted that slavery was contrary to God’s will.

Tubman’s presence also attracted visits from activists such as the Black orator and former slave Frederick Douglass, who offered a powerful vision of a world based on the equality of all people. Besides drawing on an almost inconceivable well of bravery, Tubman was a gifted fundraiser, strategist, and organizer who spent her time in Canada marshalling her enviable range of skills to help undermine and end slavery. On her multiple trips back and forth across the border, both to gather support and to bring more people to freedom, Tubman put all of her talents to use. “She was part of a network that supported her, and she supported it. Her physical skills, her marketing skills, her great brain power — she was amazing,” Larson said.

To help Black escapees who made it across the border, Tubman founded the Fugitive Aid Society in St. Catharines. She continued to serve on its executive even after leaving Canada in 1861. Freedom seekers who had settled in St. Catharines had little to their names and struggled even further to support tired, hungry newcomers with no experience of cold weather. Indeed, Tubman’s own parents, Ben and Rit Ross, apparently found their first, mild-by-Canadian-standards Niagara winter to be a severe trial; she eventually moved them and her brother John to a house she purchased in Auburn, New York.

Although Tubman based herself in St. Catharines until 1861, it’s unlikely that she ever planned to settle there permanently. She maintained an apartment in Philadelphia and spent time on both sides of the border. Living temporarily in Canada was a purely practical choice. She told the abolitionist writer Benjamin Drew in 1855, when he was in St. Catharines to interview formerly enslaved people, “We would rather stay in our native land, if we could be as free as we are here. I think slavery is the next thing to hell.”

Among the most famous of her visitors was the impassioned American abolitionist John Brown. He journeyed north to St. Catharines in April 1858 seeking Tubman’s advice, and he came away impressed. “He is the most of a man that I ever met with,” Brown wrote afterward. He wasn’t confused about Tubman’s gender; rather, he was paying her the compliment of equating her intelligence and insight with that of a man. “I wish I could have been a fly on the wall to see that meeting,” Larson said. “He recognized her for the powerful person that she was. He was a big, tall man, and she was this petite little woman, and yet he respected her. He called her General Tubman.”

Tubman’s ability to evade detection and to inspire others made her an invaluable adviser as Brown formed plans for his ill-fated attack on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. In 1859, he led two dozen men — both Black and white — on what he saw as a God-given mission to destroy the unconscionable evil of slavery. His plan was to raid the federal armoury in the village, take weapons to arm thousands of enslaved people from nearby plantations, and begin a war against the slave owners. But a company of U.S. marines overran Brown and his followers and killed ten of his men, including two of his sons. Tried for treason and murder, Brown was executed on December 2, 1859. But his raid contributed to pushing the United States towards civil war.

When the Civil War erupted south of the border in 1861, Tubman responded eagerly, and the Union army recognized her expertise and her gift for leadership. She recruited newly freed men into the military and trained formerly enslaved women in skills needed to supply the army. She worked as an unpaid nurse and provided invaluable information as a spy, leading a band of Union scouts in South Carolina.

In June 1863, using intelligence she gathered and a plan she devised, Tubman led the Second South Carolina Volunteers in a raid on plantations and Confederate positions near the Combahee River, freeing more than seven hundred Black people from bondage. She was the first woman to command an armed expedition in the war. Once again, she risked her life for others and triumphed. As Frederick Douglass said of Tubman, “Excepting John Brown — of sacred memory — I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people.”

After the war ended, Tubman continued to work toward achieving civil rights for oppressed people. She was a determined advocate for women’s suffrage and fought for equality for Black Americans. She married one of her boarders, the much younger Civil War veteran Nelson Davis, in 1859.

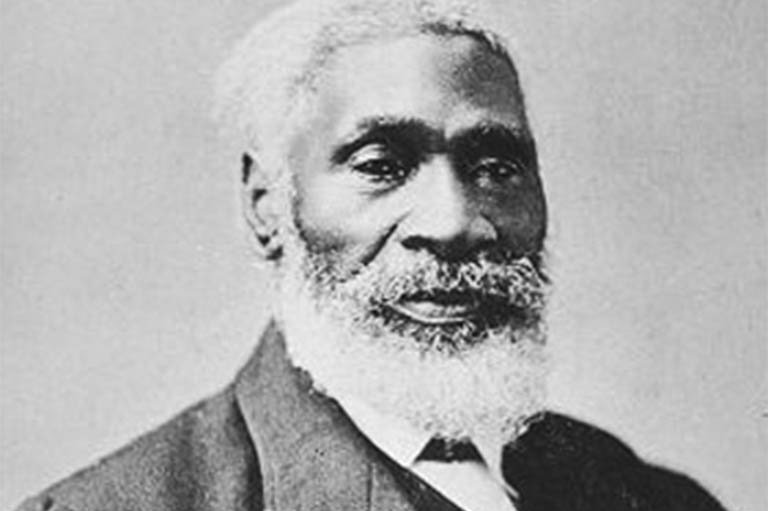

Harriet “Moses” Tubman died in 1913. The Canadian government named her a National Historic Person in 2005. The Niagara region is studded with historic sites, interpretive panels, and museum exhibits honouring Tubman, her fellow abolitionists, and the estimated thirty thousand freedom seekers who fled to Canada to escape slavery during the nineteenth century. Some of those include Josiah Henson — who may have been the inspiration for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin and whose landing spot is now known as Freedom Park — and Rev. Anthony Burns, who was ransomed from slavery and came to Canada to be a pastor.

At the St. Catharines church where Tubman worshipped, her words after the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act are inscribed: “I wouldn’t trust Uncle Sam with my people no longer. I brought them all clear off to Canada.”

Advertisement

Slavery and Emancipation in Upper Canada

From the sixteenth century to the early nineteenth century, the British and French empires forced millions of African men, women, and children, and their descendants, into slavery. Canadian historians have documented more than five thousand Black and Indigenous people living in slavery from the late 1600s to the early 1800s in the area that now comprises Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime provinces.

Evidence exists of both free and enslaved Black people living in the area that is now Ontario starting in the mid- 1700s. Accounts from the 1740s and 1750s describe Black fur traders operating out of the region around Niagara Falls, between lakes Erie and Ontario, when that area still belonged to New France. The first recorded Black slave in the area was Sophia Burden. Born in the British colonial province of New York (which later became New York State), she was sold to Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant in the 1770s and remained enslaved until 1792.

During the American Revolution from 1776 to 1783, the British government promised land, freedom, and rights to Black soldiers who would fight for the Crown against the revolutionaries. Tens of thousands of Black people joined the British side, and nearly four thousand of them emigrated to Canada after the British defeat. Although the vast majority settled in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, some arrived in the area now known as southern Ontario (then part of the Province of Quebec and re-designated as Upper Canada in 1791).

However, British law also enabled slaveholding white Loyalists to immigrate to Canada and to retain possession of their slaves.

In 1793, Upper Canada Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe, an abolitionist, proposed the first law in the British Empire to restrict slavery. A compromise with the slaveowning members of Upper Canada’s Legislative Council, the Act to Prevent the further Introduction of Slaves and to Limit the Term of Contracts for Servitude, enacted on July 9, 1793, did not liberate any slaves already living in Upper Canada. However, the bill banned the trading and importation of new slaves into the colony, and it ensured that any fugitives arriving in Upper Canada would automatically be free. As well, any child born of enslaved parents would be freed after reaching the age of twenty-five. In this way, the bill ensured that slavery would eventually die out in Upper Canada. In 1807, Britain passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, making it illegal to buy or sell human beings in the British Empire.

During the War of 1812, hundreds of Black men fought to defend Upper Canada against American invasion. American soldiers returning to their homes in the South after the war told tales of free Black men wearing British military redcoats, and they reported that escaped slaves became free when they reached Canadian soil. This news prompted increasing numbers of enslaved African Americans to risk the long and dangerous trek to Canada.

By the time slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1834, there were very few enslaved people left in Canada. However, in the United States slavery remained legal in more than a dozen southern states.

In 1850 the United States passed the Fugitive Slave Act that allowed slave owners to track down and recapture freedom seekers who had escaped into the free states of the northern U.S. “From 1850 to 1860, therefore, the [Black] immigration that had been a trickling stream ever since the War of 1812 became a regular torrent,” historian Fred Landon wrote in his article “Canada’s Part in Freeing the Slave,” published by the Ontario Historical Society.

By the eve of the U.S. Civil War in 1861, an estimated twenty thousand to seventy-five thousand Black freedom seekers had settled in the area that is now southern Ontario. However, after the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, many of those people returned to the United States.

The 1881 census put the Black population of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick at 21,500 people, or 0.6 per cent of the total population of eastern Canada. — Kate Jaimet

Restoring Moses’ Church

In the 1800s, the British Methodist Episcopal Church in St. Catharines, Ontario, today known as the Salem Chapel, hosted anti-slavery meetings and lectures and provided shelter and aid to people fleeing slavery.

One of those people was Harriet Tubman. As a 1990 newspaper proclamation declaring March 10 Harriet Tubman Day in St. Catharines put it, the church “was the place of worship and the source of strength and encouragement for Harriet Tubman and her people, and continues today to be a place of worship and a repository of Black culture and heritage for many of their descendants.”

Construction on the building started in 1853. “It was freedom seekers who built the church that Tubman belonged to. She and her brothers probably helped build it,” said her biographer, historian Kate Clifford Larson. “She gave herself up to God and followed what she believed [his] instructions to be.” Although the church was restored in the 1950s, parts of the original decor have been preserved.

The church’s historian Rochelle Bush, who belongs to the congregation and conducts tours celebrating Tubman’s legacy, took that legacy for granted while growing up in the area. “It never truly registered until I went to the United States and heard African Americans talking about coming to Canada and the Salem Chapel. We get visitors who just want to sit in the pew where Harriet may have sat and where the freedom seekers sat.”

A plaque outlining Tubman’s achievements stands outside the church. It was accompanied by a bust of Tubman until October 2021, when the bust was knocked over and smashed. Police charged a twenty-four-year old man of no fixed address with mischief and said there was no evidence the act was motivated by hate. Thanks to donors, a new bronze bust will be erected in 2022.

In the past ten years, most of Bush’s tour guests have been African Americans. But recently more Canadians have arrived. In January 2021 the federal government announced a $100,000 grant for renovations, which supplemented the chapel’s crowdfunding campaign. “We want to maintain a place of worship, but with the history woven throughout,” said Bush. “The visitors do keep the doors open. Freedom seekers built the church to worship the Lord. I would like to see it continue.” — Nancy Payne

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement