Sin City

Chris Mathieson peers into a dark, narrow alley where a handful of people are going about the business of shooting up, being high, or just hanging out, with their shopping carts piled high with their worldly goods.

“I don’t take people here on every tour,” says Mathieson as he offers a friendly wave to the people in the alley. “They have a right to their privacy. We are walking through their living room.”

Having determined they are open to having visitors, Mathieson, executive director of the Vancouver Police Museum, leads me deep into the home of the homeless — one of several stops on the museum’s popular Sins of the City tour.

This city’s poorest, most desperate and drug-infested neighbourhood may not be first on the list of attractions the average visitor — Olympic or otherwise — wants to see. But an adventurous history buff sees it differently. After all, this is where the city of Vancouver was born.

If you want to know Vancouver from its roots, you tear yourself away from the gleaming glass and steel skyscrapers and you walk a few blocks east, where sushi gives way to soup kitchens, brew pubs give way to Canada’s first safe injection site, and relentless development bumps up against determined community activism.

“This building,” says Mathieson, pointing to a century-old structure in the alley covered with graffiti opposing its demolition, “is going to be a condo.”

It’s as difficult to imagine a shiny new condo development in this grimy alley’s future as it is to imagine its past as a bustling Chinatown market alive with the squawking of fowl, the shouts of gamblers, and the drift of opium smoke.

The first Chinese came to British Columbia in 1858 by way of California, lured by the gold fields.

They were followed in the 1880s by a much larger wave when Canada recruited 17,000 labourers from southern China to build the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Many stayed to settle on the railway’s final stop — Vancouver — where they established what is today the largest historic Chinatown in Canada.

At the time, many Caucasian residents resented the influx of Chinese. On September 7, 1907, the city erupted in violence as a white mob attacked residents and smashed storefronts in Chinatown and Japantown.

A sidewalk mosaic commemorating the riot is now located at Gore and Powell streets.

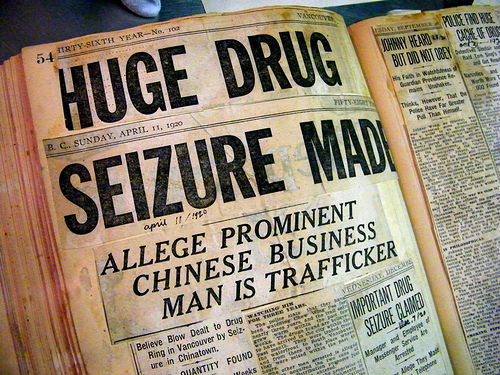

Interestingly enough, the aftermath of the race riot led to Canada’s first drug laws.

A federal inquiry into the riot was led by then Deputy Labour Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, who was alarmed at the extent of the opium trade. Opium was from then on illegal.

“Ironically, Vancouver, seen today as the centre for drug decriminalization, is also the birthplace of Canada’s drug laws,” said Mathieson.

Back in 1908, when the new opium law came into effect, Vancouver police officers suddenly had a lot of work on their hands. Raids on drug dens forced opium buyers and sellers underground — literally.

Some shops in Chinatown still have hidden trap doors leading to underground hideaways. Opium raids were as common as crack busts today.

The Vancouver Police Museum has photographic evidence, such as officers proudly displaying a canoe full of opium canisters and smugglers’ vests filled with the narcotic.

The museum also has displays of opium pipes, as well as more modern-day drug paraphernalia — making it easy to see the link between today’s Eastside drug culture and the opium dens of the past.

The tour continues to an area just northwest of Chinatown, near the CPR tracks and the harbour, called Gastown.

This is seen as the true birthplace of Vancouver, the spot where “Gassy Jack” — a.k.a. Captain John Deighton — established the Globe Saloon in 1867 to quench the thirst of workers at the newly established Stamps lumber mill.

Young and single, the lumbermen were easily tempted to spend their earnings on gambling, alcohol, and sex — and quick to become destitute when a workplace accident left them disabled.

“When people today can see that there is a link between the soup kitchens that catered to the lumberjacks and the soup kitchens of today, it changes their perception of this neighbourhood,” says Mathieson.

Indeed, changing perceptions is what the museum’s Sins of the City tour is all about.

It was established five years ago as an educational program for high school students, but then expanded to include the general public as a way to get people to come to the Downtown Eastside.

The tour takes people into the Carnegie Community Centre — the beautiful library at Hastings and Main built with funds donated by American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie in 1903.

It’s still a library, but it’s main function today is as a drop-in social services centre. The tour also gives you a glimpse of yesterday’s sex trade. It’s said that Vancouver received a sudden influx of hundreds of prostitutes after women were displaced by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Eventually, a number of brothels went up along Alexander Street, which is located near the waterfront.

The Eastside used to boast about thirty strip clubs in the ’70s, when such places peaked in popularity. Now there are just four, including the famous No. 5 Orange on Main Street — painted all orange, of course — where famous exotic dancers such as Courtney Love plied their trade.

The police museum itself is not to be missed. It contains some unusual, if ghastly, exhibits. For example, check out the preserved body parts in the autopsy room — the very room where Errol Flynn was autopsied when he died in Vancouver in 1959.

The museum also holds the rather unwieldy-looking “Harger Drunkometer” that in 1953 recorded Canada’s first impaired driving conviction with “the use of scientific aid.”

At seven dollars admission, the police museum is probably one of the least expensive attractions you’ll find in Vancouver. It’s certainly one of the most memorable. After all, how many museums ask you to “Please, do not touch the skulls”?

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement