Klondike Adventure

Those who travelled Yukon’s 531-kilometre Overland Trail from Whitehorse to Dawson City never forgot the experience. The trail was punched through the wilderness in 1902 as a way to move mail and freight in the winter, when rivers froze over. It also gave Dawsonites a way out on horse-drawn White Pass sleighs.

Travellers included Martha Black, whose husband, George Black, was Yukon commissioner from 1912 to 1918, while Martha later represented Yukon as Canada’s second female MP. In her 1938 book My Seventy Years she tells of experiencing “a clear, cold aurora night, with glorious prism-coloured northern lights flaming and dancing across the heavens.”

Crossing the Stewart River, the winter ice was unsafe, so mail and luggage were pulled across on hand sleds. Horses were led one by one, while passengers walked, negotiating the last ten metres on duckboards across thin ice.

Roadhouses about thirty-five kilometres apart provided warmth, food, beds, outhouses, and stables with fresh horses. Travelling from Whitehorse to Dawson today along the North Klondike Highway, my husband, Gord, and I visit the remains of some of those roadhouses.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Not far from Whitehorse, veering west to soak in the Takhini Hot Springs, we follow a small portion of the Overland Trail. A longer section from the Takhini River to Braeburn is used by the annual Yukon Quest dogsled race.

Heading north again on the highway, we pass Lake Laberge, which was made famous by Robert Service in his poem “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” At Braeburn, Braeburn Lodge is famous for its big cinnamon buns — one will last you until you reach the Montague Roadhouse, one of fifty-two roadhouses listed by the Whitehorse Star newspaper in 1901. Most are now crumbling, but this one has been stabilized. Historic signs with photos describe legendary hosts, drivers of six-horse teams, and giant sleighs.

In 1909, Laura Berton — a young teacher and, later, the mother of writer Pierre Berton — boarded a sleigh in Whitehorse at 4:00 a.m. with the temperature at forty below. She wore two suits plus long coats, all topped by a man’s coonskin coat. “Off we went into the silent night and into a silent world of white. For five days we would sit in this open sleigh, our noses icicled, our feet warmed by hot bricks and charcoal,” she wrote in her 1954 book I Married the Klondike, adding: “I have never embarked on a stranger journey.”

They stopped at roadhouses with giant heaters and iron racks for drying clothes. In one place, a long table was laden with roast moose, caribou, mountain sheep, baked beans, and blueberry pie. At night she had a tiny cubicle with a bed.

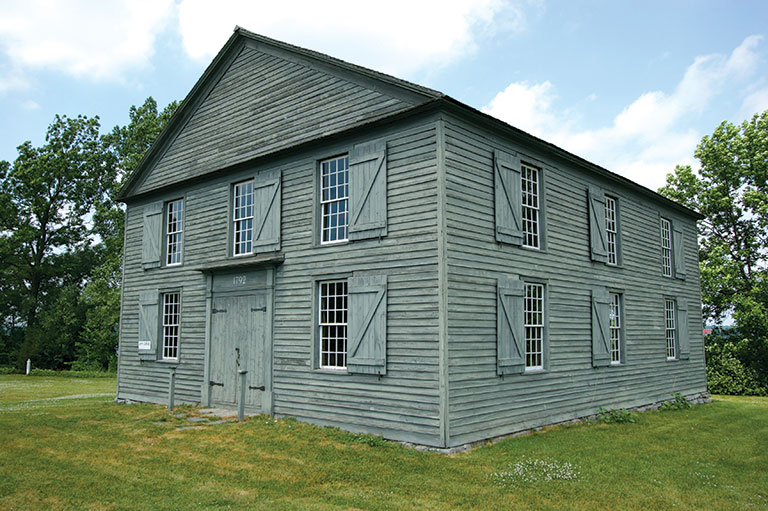

Stop at Carmacks today to see the two-storey former roadhouse that could seat forty or fifty people for a meal, while a room upstairs had twenty beds. A sign points the way to the Overland Trail, where it’s possible to bike, hike, or ski.

North of Carmacks, a viewing platform overlooks Five Finger Rapids, an obstacle that was faced by anyone moving down the Yukon River to Dawson in search of gold during the Klondike rush. Further north at Minto, a short side-road leads to the remains of a roadhouse and outbuildings. This was formerly a riverboat landing and vibrant trading post.

We take an evening boat trip from Minto. Our driver turns off the motor and lets us drift down the Yukon. The river talks to us, its sound incessant. As it swirls and eddies over its uneven bottom, it throws sediment noisily against the sides of the boat — making a powerful but peaceful sound.

The air is fragrant from the willows along the shore. We come to steep ragged cliffs where we see peregrine falcons flying. There is a pair of eagles, one on either side of the wide river. The water swirls around islands and turns our boat around as we come upon a family of mergansers.

We can see the old trail along the riverbank, and we marvel at the men who in 1902 cleared timber and used pickaxes, horse-drawn ploughs, and scrapers to level the earth and to build up the roadbed with rocks.

Between Christmas and New Year’s of 1912, George Black set out from Dawson in a forty-horsepower automobile to travel to Whitehorse on the Overland Trail. The Yukon Territorial Council was asking Ottawa for fifty thousand dollars to upgrade the trail, and it needed to prove that winter travel by automobile was possible.

December daylight didn’t last long, so Black and his companions drove mostly in darkness in a car with one headlight. The temperature dipped to forty-nine below, but Black said their furs kept them warm. At one point when the car stopped, a dog team was sent to a roadhouse for gas. While they waited, the engine froze. They built a fire under the car to thaw the oil and were off again. The round trip took fifty-six hours. News of their success was telegraphed to Ottawa, and the bill that provided the funding was passed.

Fort Selkirk has no road access, but you can visit the well-maintained historic village and former trading post near the junction of two rivers by taking a boat either from Minto, on the Yukon River, or from Pelly Crossing, on the Pelly River. The Selkirk First Nation and Yukon government jointly manage the historic site.

In 1916, travel writer Frank Carpenter braved part of the Overland Trail in the summer with a driver named “Caterpillar” Ike. Carpenter wrote in a book chapter entitled “By Motor Car Through the Wilderness” that the route “twists about like a cork-screw, as though the surveyors had laid their lines along the trail of a rabbit, and a drunken rabbit at that.” At one point they were down to the axles in mud and had to cut trees to make a corduroy road to get the car out.

But Carpenter also described the trail as a beautiful garden with great beds of pink fireweed. When they stopped to change a tire, he counted nineteen varieties of wild flowers. They once saw lynx leaping across the trail.

As we continue the drive north to Dawson on the Klondike Highway, remembering the hardy souls who travelled the Overland Trail adds another dimension to our Yukon vacation.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

IF YOU GO

STAY: In Whitehorse and Dawson there are hotels, cabins, and B & Bs. Along the Klondike Highway you’ll find campgrounds and RV parks.

SEE AND DO: In Whitehorse see Miles Canyon and visit the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. At Takhini Hot Springs, explore the Yukon Wildlife Preserve. Find some time to hike or bike on the Overland Trail. And at Dawson you can pan for gold along Bonanza Creek, hike or drive to the top of the Midnight Dome to overlook the city where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon, take a guided cruise aboard the Klondike Spirit, or visit the Dänojà Zho Cultural Centre to learn about Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in history and culture.

READ: I Married the Klondike, by Laura Berton; Carpenter’s World Travels: Canada and Newfoundland, by Frank G. Carpenter; and Irrepressible: Yukon’s Martha Black — From Gold Rush to Parliament Hill, by Enid Mallory.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement