Blackfoot Legacy

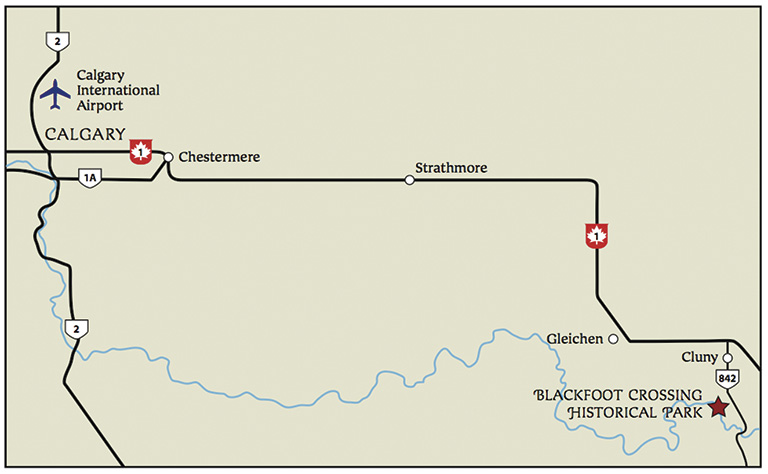

About an hour east of Calgary, I turned off the Trans-Canada Highway and headed down a lonely prairie road bordered by sweet-smelling, grey-blue sage into the Alberta Badlands.

Passing a small memorial to Chief Crowfoot — who signed Canada’s Treaty Number 7 — I caught my first glimpse of a shimmering glass-and-stone building. Alone on the crest of a hill, it overlooks the lush Bow River Valley and nearly nine hundred hectares of undulating prairie.

I was in Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park, a world-renowned First Nation tourist destination in Canada.

Owned and operated by the Siksika Band of the Blackfoot Confederacy, it blends historic traditions with modern-day tourism.

The idea for a memorial came from Prince Charles, who in 1977, while attending the 100th anniversary celebration of Treaty Number 7, suggested “Blackfoot Crossing should be officially remembered.”

Prince Charles’ suggestion slowly gathered momentum with Siksika elders.

Headed by Chief Stratten Crowfoot, they envisioned a tourist centre to showcase their heritage.

The First Nation donated fifteen square kilometres of parkland.

Meanwhile, Calgary architect Ron Goodfellow prepared design drawings. For ideas, he interviewed tribal elders, reviewed historic photographs, and read up on Blackfoot history — from their nomadic lifestyle following the great herds of buffalo, to the intrusion of the first European explorers and settlers, to modern times.

“We scratched for money, getting small grants here and there,” Goodfellow says. “Just when we were ready to start, the province cut our funds and we went on hold for ten years.”

All was not lost. In 2002, thanks to the determination of the Siksika people, the federal and provincial governments agreed to help the Siksika Nation to finance the centre. Soon after, then-Alberta Premier Ralph Klein was turning the sod on the project.

The interpretive centre opened on July 18, 2007. The building is crescent-shaped, its footprint resembling a flattened teepee.

On its long, flat roof are seven stylized aluminum teepees representing the Seven Sacred Societies and creating the symbol of an ancient First Nation encampment. Four of these teepees extend through the building to become dioramas depicting important cycles of Blackfoot history.

I passed under a canopy of blue and red stained glass, shaped to resemble sacred eagle feathers. I entered through the east-facing entrance, designed to greet the rising sun.

In front of me was a vast two-storey window overlooking the valley. It was there, in 1877, that thou-sands of Blackfoot gathered to witness Chief Crowfoot sign Treaty Number 7 with representatives of Queen Victoria and the new Canadian government.

With the treaty, they exchanged vast tracts of their traditional land for promises that included protection from whisky traders, and assistance in changing from a nomadic existence to farming on reserves.

Still inside the centre, I heard sounds of drumming echo through the halls from a nearby one hundred-seat theatre. On the stage, chicken dancers — splendidly turned out in buckskin trimmed with intricate patterns of tiny coloured beads and wearing magnificent feathered headdresses — whirled to the sounds of haunting chants and beating drums.

“Beads and eagle feathers are as much part of our prairie culture as our teepee,” explained Judy Royal, senior interpreter of Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park, as we wound our way down a glass-encased stairway to the lower level.

From nearby story panels, I discovered that when Chief Crowfoot died in 1890 he was totally disillusioned. His people were diseased and starving. The huge herds of bison that had darkened the prairies had disappeared, and settlers had encroached on their land.

The government, meanwhile, had failed to live up to the terms of the treaty. Soon, their problems multiplied. The Blackfoot had trouble with Indian agents. Later, their children were seized and sent to residential schools.

“Now,” says Royal, “we are learning from the past, and looking to the future and relearning our past.”

Today, a different type of teepee encampment welcomes visitors.

About half a kilometre from the centre, visitors can experience the traditional Blackfoot lifestyle at Buffalo Jump Tipi Village.

Its modern-day teepees are complete with small stoves, cots, blankets, water, and a lantern. “Our campers hike, bird-watch, and listen to the storyteller around a campfire under the stars,” says Ken Heatly, the teepee coordinator for the cultural centre.

As we toured the surroundings in a modified golf cart, Heatly pointed out an archaeolgical site where there are traces of an earth lodge village. This mysterious place was once a fortified village surrounded by a moat.

The site was once home to people thought to have come from the Mandan tribes of North Dakota more than 250 years ago. They lived in mud huts, not teepees, and eventually disappeared.

Back on the sage-bordered road, I took a last look at the solitary building on the old bison trail. I was awed by the determination of the small band of the Siksika Nation to promote and preserve its culture and traditions.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement