History Teaching "Mash-up"

Over the years, I have developed resources and written papers that address the challenge of adding women to established historical narratives taught in schools. I co-authored a women’s primary resource textbook to support the Ontario grade 10 Canadian history course, entitled Unfolding Power, Documents in 20th century Canadian Women’s History (Green Dragon Press, 2004), now out of print.

I developed a wide range of theme-specific classroom resources and wrote a number of academic articles that trace the history of feminist activists. I also founded a local women’s history talk series, herstoriescafe.com.

Honestly, change has been slow and limited.

School textbooks and resources continue to place women’s historical experiences within topic areas that have existed for over one hundred years. The topic areas contain accepted national narratives, framed within a privileged male focus that perpetuate common categories and representations.

When women are added, they are singled out, as exceptionalities. Their experiences are often cased within the “roles” they played, implying they enter the stage briefly and then exit, without much fuss.

That approach doesn’t always honour women’s historical experiences or support students to understand the complex interrelationships that exist between people, land, and communities.

History teachers cannot be expected to do the work that textbooks and resources should do to address gender equity, but teachers have an opportunity to disrupt the structures that place the study of history within established themes and timelines.

I am proposing a new framework, one that provides a “mash-up” of people and events; a restructuring of the curriculum content that brings together what appear to be unrelated stories.

Mixing up the content narratives can provide an alternative way to explore the past, freeing up students to develop new inquiries and explore new perspectives. It has the added bonus of more accurately incorporating women’s voices.

The inspiration

This alternative method evolved out of a visit I had to a friend’s home. Her children are aged 8 and 12. Knowing that I teach history, they encouraged me to join them as they watched The Who Was? Show, on Netflix, based on a series of books with the same name.

The books explore notable individuals from the past and focus on their achievements, making links to the time period in which they lived. When the books were transformed into a live-action sketch comedy, the writers chose to mix up the characters.

One show features Galileo and Queen Elizabeth I, for example, and another show, Isaac Newton and Amelia Earhart. One has to ask: Do these individuals have anything in common? If you think hard enough you will probably find a number of things!

This inspired me to think about the idea of teaching history by focusing less on traditional chronological timelines of people, places, and events and more on the common elements between individuals and their lives. What I found was that this new approach was much more engaging to study; it respected multiple and diverse voices, and allowed for the messiness of real lived experiences.

The problem with presenting traditional linear portrayals of past events is that it can make history appear predictable and inevitable. This new “mash-up” method challenges the established singular themes and allows for new stories to emerge. The study of history can now become an adventure that has unlimited parameters.

Let’s look at an example.

What are some strategies for “mashing up” our approach to teaching the First World War?

i) Alter the standard divisions of content. Resources and curriculum frequently frame the history of the war within a chronology of battle dates, victories, and military action. But, what if we combined the study of the home front and the study of combat?

If we link these topics together, focusing broadly on the military industrial complex, we can examine the resources and systems required to create, sustain, and maintain the war.

When we approach the study of war this way, women do not play a minor “role” in the war - stepping in temporarily to replace men - but rather they are integral to the production and continuation of the war through their complex contributions in their communities, on the land, and in war work.

ii) “Mash-up” your primary sources. Women, Indigenous communities, and minority cultures are often included in textbooks as sidebars and portrayed for their unique or supportive “roles.”

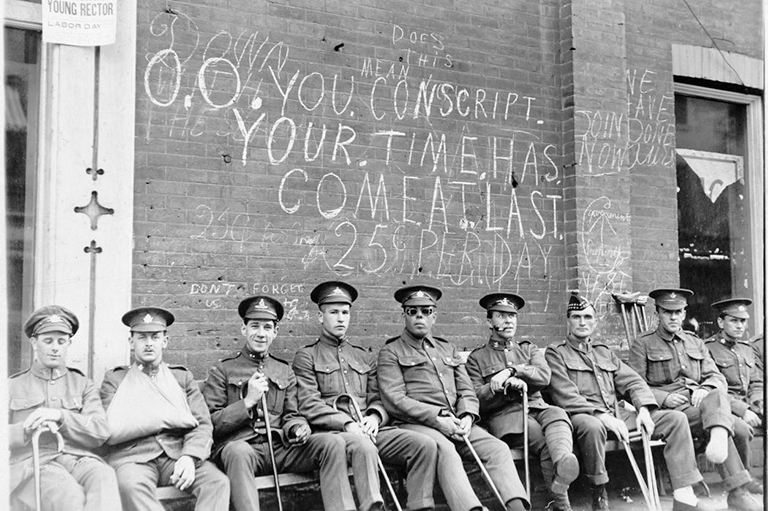

Teachers can include their voices in the broader examination of war by mixing up the documents. What questions might emerge when we show images of women preparing war supplies, alongside women and men in hospitals, and images of men in combat?

Trench warfare, for example, is dependent on supplies: uniforms, food, war weapons, military equipment, and medical aid—in which thousands of women were responsible for producing, aiding, and maintaining. Bringing these elements of war together, better illustrate the military industrial complex, and expand our inquiries.

What if we examine images that represent some of the outcomes of war?

iii) “Mash-up” the voices of war. Teachers can use the arts to integrate voices both for and against the war, including soldiers, anti-war activists, the voices of families and children, along with women suffrage narratives.

So, like The Who Was? Show, perhaps a “mash-up” lesson might include:

- Teacher Winnifred Cassel, working on a farm in Ontario during the war,

- Flora Dennison, a factory worker, fighting for women’s rights,

- And the letters of Private Fraser, Canadian Expeditionary Force, who wrote a journal that documented his experiences in overseas combat.

What they have in common is the war—the complexities more evident by placing their stories together.

The role of critical thinking

Central to this approach is a focus on critical thinking and encouraging students to come up with strong, complex questions. The questions we ask are as important as the historical examinations we explore.

When we present content to our students following traditional narratives and compartmentalization, then the questions we ask may perpetuate established understandings about the past.

For example, a question about what happened when nations went to war, tends to focus on the actions of political leaders, industrial, and military men.

This marginalizes the experiences of women who were denied a voice or access to professional positions but were active in diverse spaces and places. The answers to this question would look different, build on additional knowledge and analysis, if the content brought seemingly unrelated stories together.

A new approach to gender analysis

Gender is a central category of analysis. Adding women to established male-focused narratives as an afterthought, limits the entire historical analysis. Not only does it leave women out, but also it leaves out the complex interconnections that exist within our societies.

If we believe that nations survive when the voices of all are represented, heard, and respected equally, then as history teachers we need to broaden our teaching and find ways to add diverse perspectives.

We can do this by “mixing up” the evidence we provide, the narratives and stories we share, and the topics and categories we focus on.

Let’s try “mashing-up” our history teaching together!

I am looking for teachers who would like to work with me and try out some of these ideas in their classes. Please write to me if you are interested: rose.fine.meyer@utoronto.ca

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement