Saving Sweet & Sour

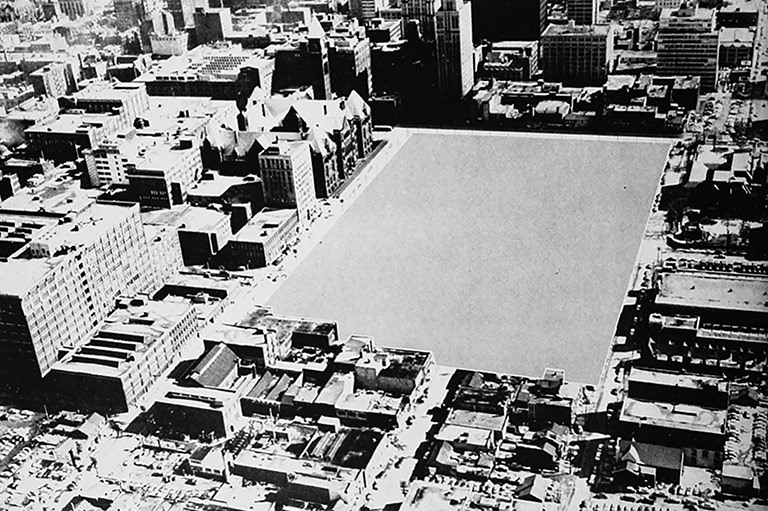

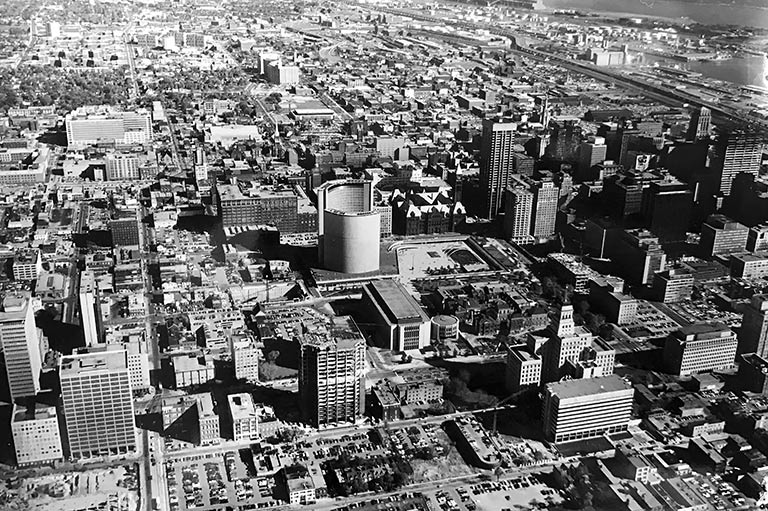

In the decade between 1947 and 1958, the City of Toronto bulldozed two-thirds of its Chinatown. Homes and businesses that had been held by Chinese Canadians for half a century were razed. Banks, community centres, newspaper offices, music societies, and schools fell to the wrecking ball. By the time the dust settled, heavy machinery had flattened several blocks of downtown Toronto. The way was clear for a shiny new city hall to rise at the intersection of Queen and Bay streets, on what would become Canada’s largest civic plaza, Nathan Phillips Square.

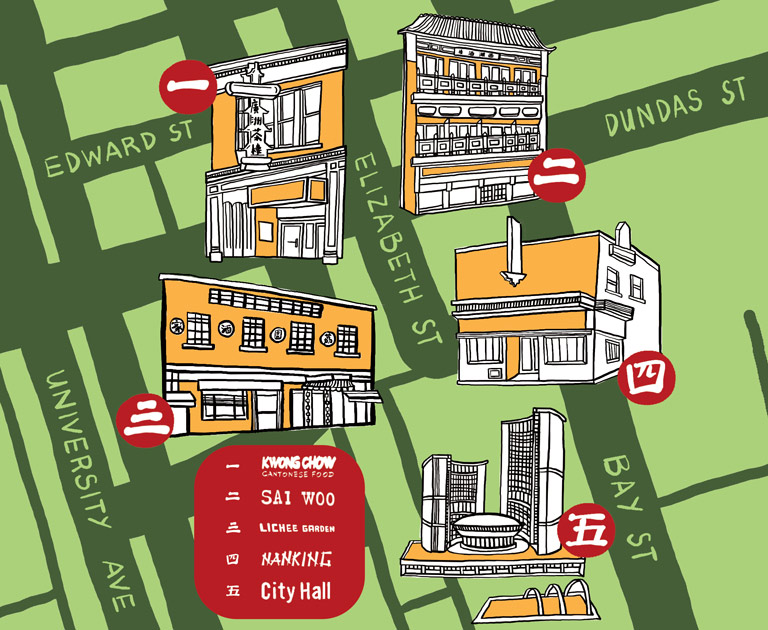

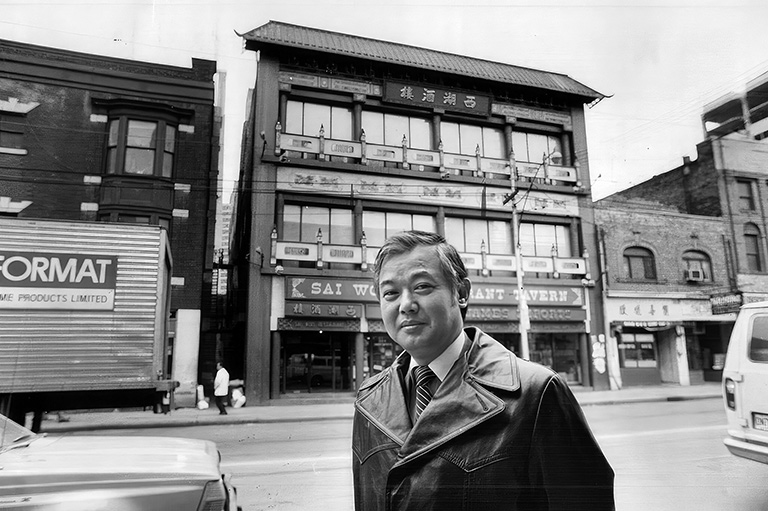

What remained of Chinatown was primarily composed of businesses that served people outside of the community, with a few local organizations sprinkled throughout. Among these businesses stood the “Big Four” Chinese restaurants: Lichee Garden, Nanking Tavern, Sai Woo, and Kwong Chow. Opened during the very decade of the demolition, these restaurants mainly catered to non-Chinese diners, serving food that would be mocked as “inauthentic” today: dishes like chop suey, sweet-and-sour pork, egg foo young, and chicken balls with sweet-and-sour sauce. Torontonians had become familiar with these dishes from the takeaway chop-suey shops that were popular in the city, but the Big Four went beyond cheap eats and presented Chinese dining as an elegant, sit-down affair. As some of the first restaurants in Toronto to obtain liquor licences, the Big Four boasted menus that contained hundreds of dishes, served in air-conditioned dining rooms that could seat multitudes of people.

The individuals behind these restaurants were entrepreneurs, community leaders, and innovators who created connections with all sections of Toronto society — from everyday diners to the local and federal elites whom they wined and dined with lavish banquets. By fundamentally altering how Torontonians ate Chinese cuisine and how they thought about Chinatown, these restaurateurs used food to change hearts, minds, and stomachs in their effort to save the remaining part of their neighbourhood.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

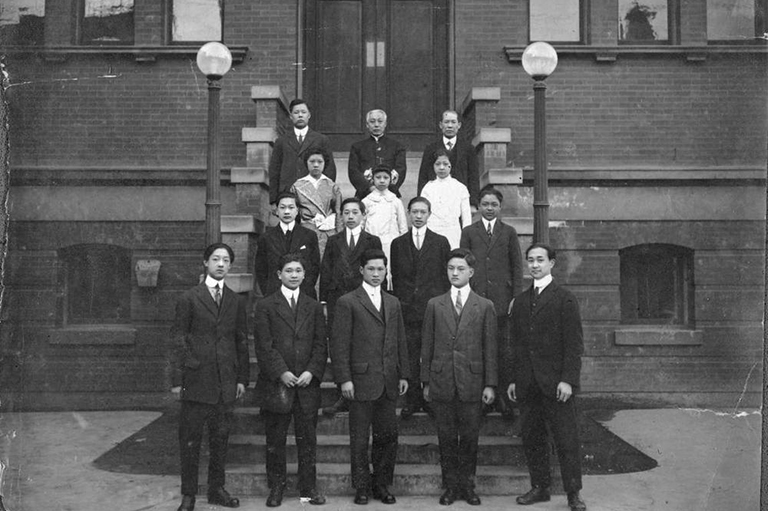

Beginning in the nineteenth century, Chinese communities in Canada established Chinatowns to pool resources and to shelter themselves from racial discrimination. Exclusion and anti-Asian racism marked Canada’s immigration and social fabric from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, two key examples being the head tax, imposed from 1885 to 1923, and the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923.

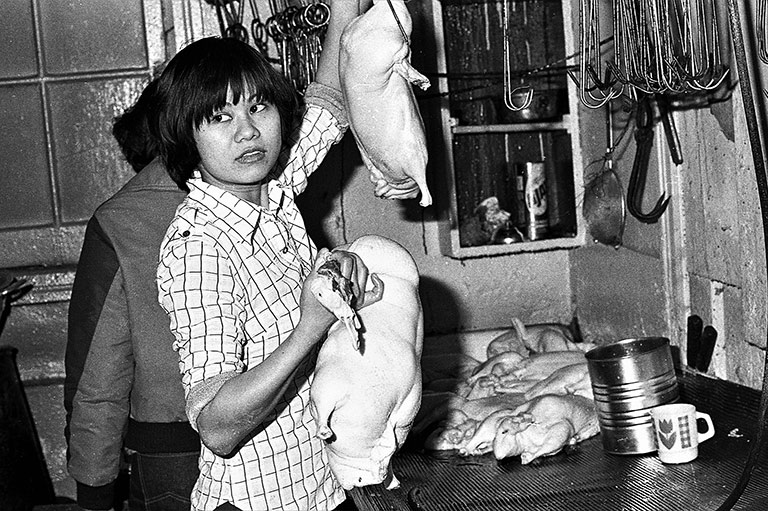

Using the Canadian Pacific Railway that they had helped to build, Chinese workers quickly established Chinatowns along the railway line, setting down roots in Canada from coast to coast. Yet these communities were never isolated from the world that surrounded them. Limited by prejudices and federal, provincial, and local laws that made it difficult for them to undertake certain professions and businesses, early Chinese workers opened laundries, grocery stores, and restaurants, which served as key sources of employment and also welcomed outside clientele into Chinatowns.

Toronto was no exception. Chinese migrants first came to the city at the end of the nineteenth century, and by the 1920s they had established a Chinatown in an area known as the Ward. Less than one square kilometre in area, the densely populated residential neighbourhood was located close to the railway’s Union Station and Toronto’s old city hall. Bounded by Queen Street West to the south, College Street to the north, University Avenue to the west, and Yonge Street to the east, the Ward was the entry point for some of the city’s earliest Italian, Jewish, and Black communities.

Offering low-cost housing for often working-class immigrants, the Ward was consistently branded as a slum by city inspectors and outside onlookers. Concerns around public health, landlord neglect, and closely packed living conditions overshadowed the vibrant communities of people who had built homes, businesses, synagogues, churches, theatres, restaurants, and even a playground in the neighbourhood. Toronto’s first Chinatown, one of the last communities to carve out a home in the Ward, was a close-knit place, where everyone knew and took care of one another.

Everything changed in Toronto in 1947. Nationally, there was cause for celebration. Canada had repealed the Chinese Immigration Act, which had effectively shut down Chinese immigration since 1923 and was one of many policies that prevented Asians from entering Canada. This repeal marked a welcome shift towards the officially multicultural Canada we know today, it and gave the community in Toronto the chance to grow, to recover, and to belong after decades of exclusion.

The news was not as fortunate locally. On January 1, 1947, Torontonians voted to approve the purchase of land around Bay and Queen streets, in the heart of Chinatown, to construct a new civic square and municipal buildings. According to historian Arlene Chan, no Chinese Torontonians were consulted, despite the fact that they owned fifty-five per cent of the buildings to be expropriated. Owners were paid significantly less than their original purchase price for the properties. By the time construction began on the new Toronto City Hall in 1961, all that remained of Chinatown was a few blocks of restaurants, mom-and-pop shops, and community organizations squeezed between the construction site and Dundas Street West.

Before the fireworks had faded over celebrations marking the opening of Toronto’s New City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square in 1965, council and developers began to eye the remaining third of Chinatown. The words “urban renewal” hummed throughout the city, and politicians like Alderman George Ben viewed the surviving third of the neighbourhood as an “eyesore” that, he told the Globe and Mail, “should be removed.”

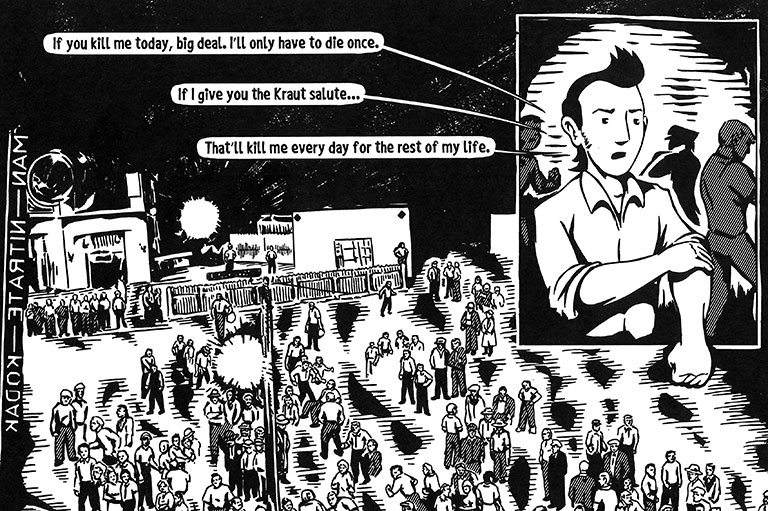

After more than a decade of expropriation and discrimination, Chinatown had lost some of its shine. Toronto Daily Star columnist Max MacPherson captured a nostalgic but pessimistic vision in his walks through the neighbourhood, writing that people “who can faintly recall the smelly glories of Chinatown in the Forties know that, by comparison, it is now a sad and stringy place.” Remaining residents sang a related tune in local newspapers. Lim Chow, whose “world” was “in danger of collapsing” with renewed efforts to develop Chinatown, told Toronto Daily Star reporter Tom Kerr in 1967 that “Chinatown is a good place” and asked: “Why can’t it stay?”

Advertisement

Even hawks like Alderman Ben had to admit that the Big Four restaurants were redeeming features of the neighbourhood. In fact, city politicians often dined in these establishments. In a 1964 article in the Toronto Telegram, columnist Ray Hill outlined the “love-ties” between city council and Chinatown, pointing out how the “law-abiding city-within-a-city” provided an answer to city councillors’ “pathetic shouts for ‘food! food!’” A Globe and Mail article the same year noted wryly how “City Council did not give a bamboo shoot for Chinatown (except at mealtimes).”

The Big Four, along with other restaurants like the Golden Dragon, visually defined Chinatown, with bright neon signs that lit up Toronto’s night. They had large banquet halls perfect for hosting extravagant parties. Decorated with beautiful Chinese paintings and outfitted with a grand piano and a live band, Lichee Garden could accommodate at least three hundred people, dining on dishes that ranged from balled chicken with pineapple to filet mignon.

Diners at the Big Four were welcomed by the charismatic owners who presided over their restaurants. Some were born in Canada, like Nanaimo, B.C., native Jean Lumb, who owned the Kwong Chow with her husband, Doyle Lumb. Jean Lumb had moved to Toronto in 1935 at the age of sixteen and eventually made enough money to bring the rest of her family to the city from B.C. She was known for her impressive memory and her ability to make every customer feel at home. Other restaurateurs had moved to Canada more recently. Bill Wen, who came to Ontario in 1953 from Guangzhou, China, became one of the eleven partners of Sai Woo in 1957 at the age of twenty-one.

Harry Lem, the owner of Lichee Garden, was deeply respected by the Chinese community and served as the head of crucial organizations like the Chinese Community Centre of Ontario. Lem often acted as a liaison between Chinatown residents and politicians. He helped newcomers settle in Toronto with the assistance of organizations like the Lem Si Ho Tong Family Association, which offered both social and financial support.

Harry Tang and Ray Lee of Nanking Tavern, which stood closest to New City Hall, were quoted frequently in newspaper stories, explaining Chinatown’s struggles to the rest of the city and advocating for its protection.

“Chinatown’s ugliness is due to the uncertainty of what’s going to happen,” Lumb told the Toronto Daily Star in 1964. “Merchants don’t want to invest in refurbishing businesses if they are going to be torn down. Remember, 75 per cent of Chinatown was expropriated over a 10-year period to make way for the new city hall — this made businessmen wary.” In the same article, Lee also shifted blame to the city, claiming: “Nothing has been done in the past few years because the city has not issued building permits for major repairs or renovations.” A few years later, in 1969, Lem reiterated to the readers of the Star: “The place is run-down because we don’t know what’s coming next year or next month. That uncertainty has discouraged improvements for years.”

If speaking to the media was one way to garner support, another, perhaps more persuasive way was to influence politicians and the city’s elite through their taste buds. From daily lunches to lavish banquets, the Big Four wined and dined many of the most powerful individuals in the local, provincial, and federal governments.

Records from two of these banquets can now be found in the William Wai Ching Wong Fonds of the Chinese Canadian Archive housed at the Toronto Public Library. Both were hosted at the Kwong Chow restaurant and organized by the Chinese Community Centre of Ontario, which, under its president W.C. Wong, was the key brokering organization between Chinatown and Toronto’s political and business leaders.

The first was held on September 25, 1965, in honour of Minister of Citizenship and Immigration John Nicholson. Also in attendance were Toronto Mayor Philip Givens and Member of Parliament Ian Wahn. In his welcome speech, Wong expressed confidence that Nicholson would be the “right man” to ameliorate the conditions for Chinese immigration to Canada and, in so doing, to increase the population and transform Canada into a “powerful country” and “a great power of the world.”

The second banquet was held on November 26, 1967, in honour of Governor General Roland Michener, who had previously served as a Member of Provincial Parliament for the Toronto riding that included Chinatown. The masters of ceremony were the current and past presidents of the Chinese Community Centre of Ontario, W.C. Wong and E.C. Mark, joined by Lumb. A welcome speech praised the Governor General as an “outstanding person in performing his duty ... [and] a good friend of Canadian ethnic groups.” To the delight of the food historian, a menu survives in the archives describing this extravagant banquet: a delicious spread of thirteen dishes that included a mixed “shark’s fin, melon, bird’s nest soup” as well as some more standard favourites like sweet-and-sour pork spareribs and jumbo shrimp, all accompanied with “Natural Jasmine Tea.” A delicacy named “New Delhi Flavoured Young Capon” was also included, possibly a nod to Michener’s time in India, which preceded his appointment as Governor General.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Although these banquets were not formally connected to the issue of saving Toronto’s Chinatown, they gave its civic and business leaders access to people in the corridors of power. Unlike in the previous decade, City Council could not brazenly bulldoze their remaining neighbourhood; instead, the parties would have to negotiate.

If city councillors were grudgingly willing to admit Chinatown’s value as a tourist attraction and dining destination, they still didn’t want it taking up prime downtown real estate. “A new showplace Chinatown ought to be created on less expensive land, possibly to the north of where it is now” argued Commissioner of Development W.F. Manthorpe in the Toronto Daily Star on March 7, 1967.

However, this commercial vision only captured a sliver of the many important functions that Chinatown had, and that leaders like Lumb were impassioned to save. “We want to build a Chinatown that will not only attract tourists, but the Chinese as well,” Lumb told the Toronto Daily Star in 1964. “The only way Chinatown can be kept alive is with Chinese people.” Like many others, Tang of the Nanking Tavern opposed the idea of moving the neighbourhood: “I think the Chinese people would like to see Chinatown left as it is,” he told the Star on February 19, 1969.

Bureaucrats and politicians were captivated by grandiose “urban renewal” plans, part of a continent-wide movement targeting older and poorer downtown neighbourhoods for commercial, residential, and transport developments. In Toronto, the Ward became one of the city’s first urban-renewal study areas, kicking off one of many fights between communities and officials over how the city should change.

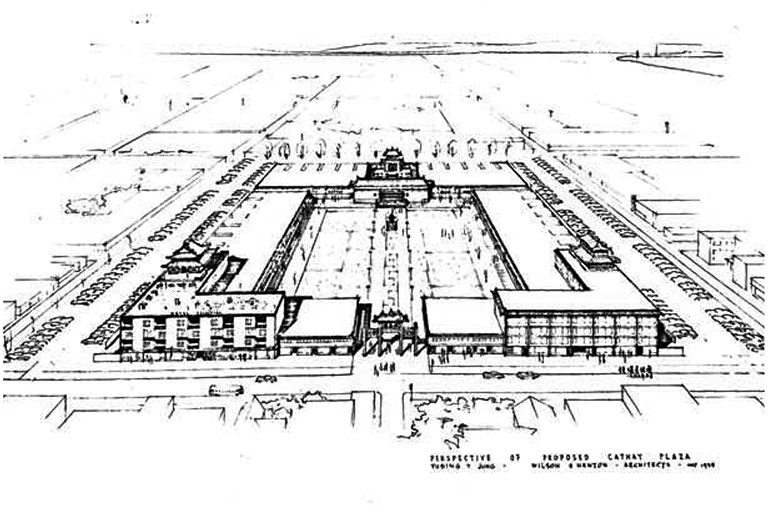

The powers at City Hall criticized Chinatown businesses and residents with the claim that they did not have concrete plans for their area. But this was far from the truth: Their leaders pitched innovative solutions that would allow their neighbourhood to remain where it was. They hired architects and networked with city officials and fellow business owners in private meetings, often held at Big Four restaurants. Some of the proposed plans are still housed in the City of Toronto archives, including one plan — complete with budget and architectural schematics — that was meant to be a “modern Chinese development of a self contained community centre … which would include a hotel, an office building or buildings, stores, a community hall and all of the recreational facilities.”

In a meal held at Lichee Garden on February 15, 1963, W.H. Clark, the chairman of the City of Toronto Planning Board, met with Harry Lem to discuss the future of Chinatown. Lem provided a list of twenty-six Chinese organizations and fifty-nine businesses located in the remaining area of the neighbourhood, which — while no longer an important residential enclave — continued to function as a commercial and cultural centre for the Chinese community.

The planning board chair expressed a desire to preserve a Chinatown but suggested moving it to another location due to “irresistible pressures for major business development north of the Civic Square.” Lem countered by emphasizing the costs of relocation and advanced that Chinatown might be able to hold its own against outside pressure if he and other business people could take on the initiative to set up a “compact Chinatown,” similar to the one in Los Angeles.

The new compact Chinatown he proposed would have a “distinctively oriental flavour by colour and design” and would involve expanding existing restaurants like Lichee Garden to include features like a nightclub and a grocery store, “which in addition to standard goods would feature oriental food.” Unlike in Los Angeles — where there was a split between the “new Chinatown of restaurants and novelty stores” that catered to tourists and “the old Chinatown with all the other things” — Lem believed Toronto’s Chinatown should include the full range of businesses and organizations that remained. For Lem and other community leaders, venues that offered good food and good times needed to grow synergistically with organizations that created community and offered social support. The meeting ended inconclusively.

Another plan suggested integrating Chinatown with the proposed Eaton Centre shopping mall — which, when it was eventually built in 1977, would stretch for half a kilometre along Yonge Street between Queen and Dundas streets west. This plan would connect the mall to the remaining part of Chinatown through a series of “small mews” that would facilitate pedestrian traffic. However, as Lumb told the Toronto Telegram in 1967, the plans had been “drawn up on a volunteer basis,” and it would “cost money to present them to the city — especially when there is no guarantee that any of them will be accepted.”

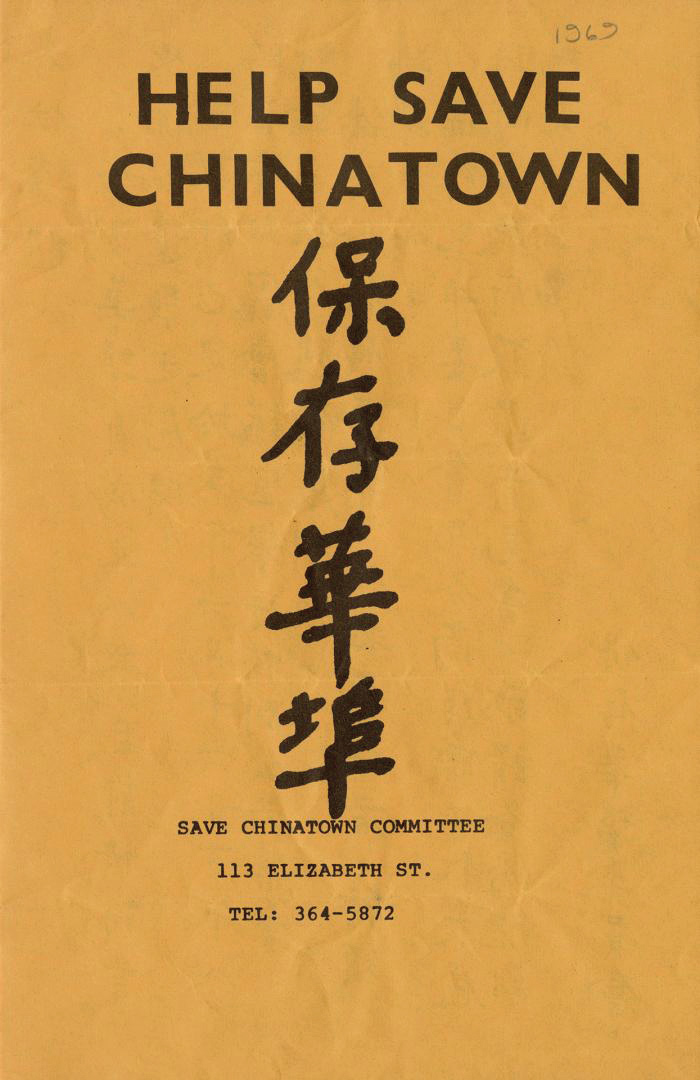

In response to the mounting pressure, a coalition was formed in 1967 that became known as the Save Chinatown Committee. Headed by Lumb, with the participation of Wong, Lem, and others, this committee conducted multiple public-relations campaigns culminating in a brief to the city in 1969.

The brief provided eleven reasons to save Chinatown that ranged from its role as a social, cultural, economic, moral, and psychological centre for Chinese Torontonians to its function as one of the biggest tourist attractions in the city. It argued that Chinatown provided a thriving social scene “in the usual drab and dead business and commerce section of [the] city after five o’clock,” and it appealed to councillors’ cosmopolitan aspirations for Toronto to emulate other “large cities of the world.”

Along with the brief, a special meeting was held at City Hall on June 16, 1969, where more than 350 Chinese Canadians stood in the City Council chambers in support of the Save Chinatown Committee. Following presentations by representatives of community and business groups as well as Members of Parliament Perry Ryan and Ian Wahn (the latter had been a guest at one of Kwong Chow’s lavish banquets in 1965), the city’s Building and Development Committee and Mayor William Dennison endorsed the principle of keeping Chinatown where it was until a new plan was formulated. Chinatown was saved, at least for the time being — a moment of success after years of efforts. Yet, as is the history with Chinatowns across North America, the fight for Toronto’s continued on, with each sweet taste of success coming with sourness of change.

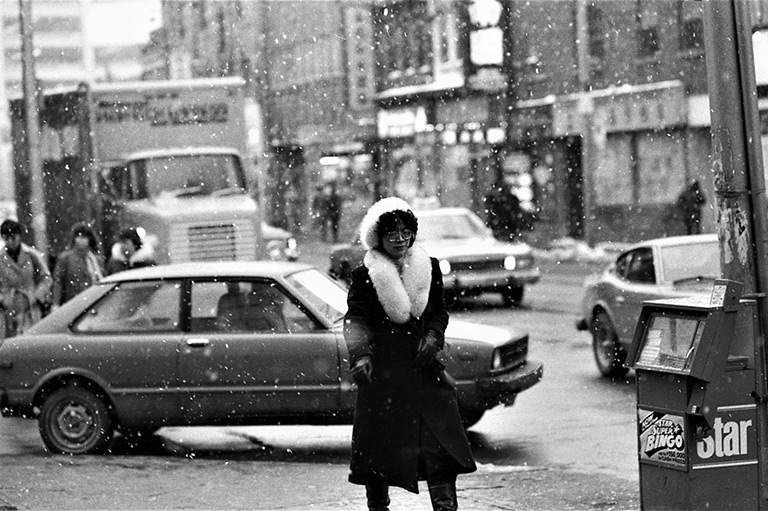

If you stand near the intersection of Elizabeth Street and Dundas Street West today, you can still see some of the old Chinatown buildings that continue to survive the pressures of redevelopment. However, several of the existing businesses are no longer Chinese, and many of the original low rises were replaced with high-rise offices and hotels in the 1980s. After the last big stand at City Hall, efforts within and outside of the Chinese-Torontonian community shifted towards new Chinatowns to the west — centred around Dundas Street West and Spadina Avenue — and to the east — centred around Broadview Avenue and Gerrard Street East.

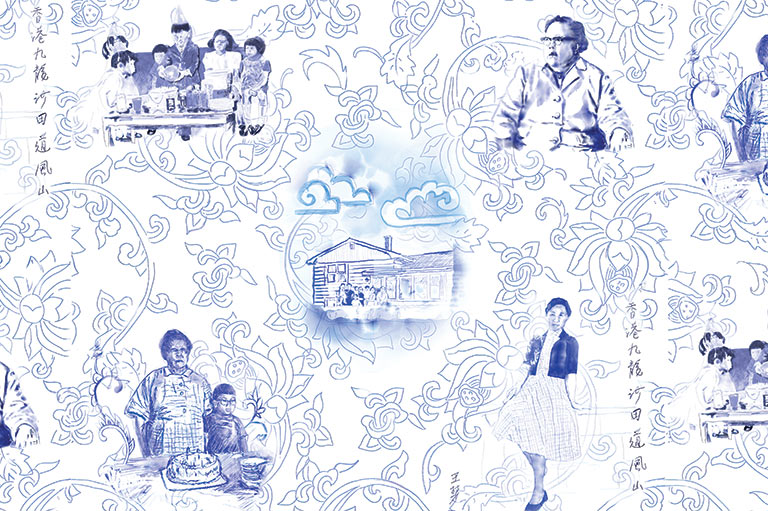

Part of this shift happened because the community itself began changing dramatically in the 1970s. Due to global events and changes in Canada’s immigration policy — notably the 1967 Immigration Act, which substituted a points-based system for the previous one that had discriminated on the basis of race, ethnicity, and national origin — Toronto welcomed many new immigrants from Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. Migrating as refugees, family members, students, and entrepreneurs, these newcomers changed the landscape of the city’s now multiple Chinatowns.

Meanwhile, the descendants of the people who had created Toronto’s first Chinatown grew up and moved throughout the city, particularly to suburbs like Markham and Richmond Hill. The remaining funds from the Save Chinatown Committee were transferred to the newly formed Toronto Chinese Business Association to help support businesses, particularly those in the western area around Spadina Avenue. New visions of Chinatown developed.

Beyond the Save Chinatown campaign, each of the Big Four restaurants had a very successful run. Nanking Tavern was the first to close in 1979, while Lichee Garden was the last in 2009, after serving diners for more than sixty years. Each restaurant moved with the times. Some literally moved around the Metro area, like Lichee Garden, which shifted to a few different locations before ending up in Thornhill. Others revamped their menus, like Kwong Chow and Sai Woo, which are often credited with introducing dim sum to Toronto.

Big Four owners and partners like Kwong Chow’s Lumb and Sai Woo’s Wen continued to be active in and beyond the Chinese community. Lumb was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1976 and became a citizenship judge who presided over hundreds of citizenship ceremonies for new Canadians. A foundation was created in her honour that, even after her passing in 2002, continues to award Chinese-Canadian youth with scholarships to attend university. Wen worked to develop connections between Canada and China, even helping to arrange the first arrival of giant pandas to the Toronto Zoo.

Chinatown did not end with the fight to save it: Chinese communities continued to adapt and flourish throughout the city. Power transferred to different organizations and community leaders, involving both recent immigrants and later-generation Chinese Canadians, each adding to the ongoing conversations about what Chinatown could and should be. While the need to preserve specific places continued, this new generation emphasized the equally if not more important need to support and focus on the people who make up Chinatown.

What has endured from the Save Chinatown campaign is a reminder to Torontonians of all backgrounds that Chinatown was — and is — not simply a tourist attraction but a place of community. The spirit of Chinatown continues on, and, although many people may only go there to enjoy something good to eat, hopefully they leave not only with a full belly but also with connections to the people who truly make Chinatown special.

Thanks to Section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada became the first country in the world to recognize multiculturalism in its Constitution. With your help, we can continue to share voices from the past that were previously silenced or ignored.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement