Something to Squawk About

He was a brandy-swilling, foul-mouthed birdbrain who managed to thwart the dreams of real estate developers in British Columbia for years. The story of Louis the parrot’s seventeen-year legal standoff with developers in Victoria may seem the stuff of legend — and yet, it’s true.

From 1949 to 1966, the ornery bird was the bane of builders who wished to tear down the mansion where the macaw lived — a prime downtown location — and replace it with high-rise apartments. In this unusual battle between progress and tradition, Louis, representing tradition, was the victor and became something of a folk hero to the city’s heritage preservationists.

“Louis roosts in and is the de facto landlord of one of the most sought-after parcels of downtown real estate in scenic British Columbia,” Life magazine reported in “The Old Bird Won’t Sell,” a story that appeared in its August 1963 issue. “In the eyes of certain businessmen ... Louis is a bone in the throat of civic progress.”

If Louis’s tale was made into a movie, the opening scene would be set in 1949, with the death of his owner, Victoria Jane Wilson — a rich, unmarried, and childless recluse who had no siblings and few friends when she died at seventy-two. Louis, a gorgeous blue-and-yellow South American macaw, had been the love of her life ever since she received him as a gift from her parents on her fifth birthday. Her will stipulated that Louis must live out his days in her mansion and that under no circumstances must his environment be disturbed. This meant that the house had to remain standing until the bird dropped dead — and parrots are blessed with very long lives.

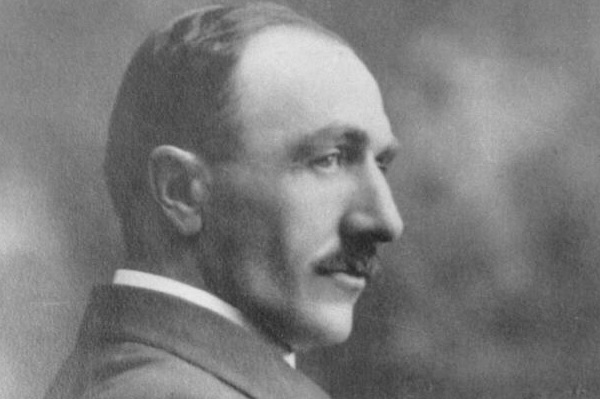

It was an irresistible story that gained international attention — as much for the absurdity of the situation as for the back story of how Wilson came to bequeath a mansion to her feathered friend. An only child, Wilson was kept apart from other youngsters by her overly protective and overbearing father, real estate tycoon (James) Keith Wilson. According to a 2012 Victoria Times Colonist “Tales from the Vault” article by Stephen Ruttan, “On the few occasions when Victoria Jane did leave the house, her father would follow her. He would be hovering in the background, occasionally dodging behind poles if she happened to talk to someone. No wonder she grew up to be painfully shy.”

Wilson lived her entire life in a three-storey gabled-roof mansion her father had built on a large piece of land on Burdett Avenue, close to the downtown area and the city’s inner harbour. Nicknamed “The White House” by local citizens due to its hue, the mansion was surrounded by a high white fence.

Within this gilded cage — filled with antique furniture, large crystal chandeliers, heavy gilt mirrors, Dresden china, ornate pillars, hand-carved staircases, and elaborately sculptured ceilings — young Victoria Jane Wilson spent her days yearning for companionship.

Visitors were rare — mostly Keith’s business associates — and Victoria Jane’s mother, Mary Kennethina, nicknamed “Kitty,” was estranged from the rest of her family. So Victoria Jane never spent any time with her cousins, and she rarely socialized with other children. Mother and daughter often didn’t leave the house for long periods of time, giving rise to local speculation that Keith wouldn’t allow them out. Thus isolated, the young girl cherished Louis's companionship

Blue-and-yellow macaws are among the largest of the parrot species; they can weigh between 900 and 1,800 grams and have a wingspan of up to 1.5 metres. They are often very intelligent, talkative, good mimics, playful, and entertaining, which is why macaws have been kept as pets for centuries.

Macaws also have relatively long lifespans. In the wild, they may live only thirty to thirty-five years, but in captivity at zoos, or as pets, they can live for many decades, with some reaching the age of one hundred or more. It is not uncommon for them to outlive their owners, as Louis did. (They are also not cheap to purchase: Today, a blue-and-yellow macaw can cost as much as $1,200.)

As the years passed, Victoria Jane Wilson’s passion for parrots intensified. The Victoria Times Colonist reported that, as a young woman, Wilson owned twenty-six budgies, six lovebirds (small, mostly green parrots with a variety of bright colours on their upper body and weighing about fifty grams), at least four Panamanian parrots (green body with a yellow head or yellow front), and a Mexican yellow-headed parrot (a short-tailed green bird with a yellow head). Eventually her collection occupied the mansion’s entire top floor. It must have been quite noisy with all the birds chattering away.

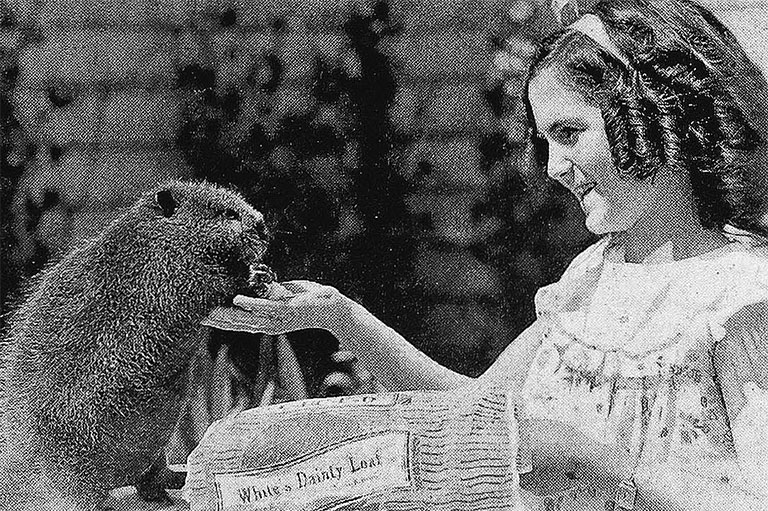

Louis, though, remained her favourite — and, as such, he was given special treatment. Typically, parrots dine on seeds, nuts, and fruit and drink only water. But Louis received unconventional extras such as hard-boiled eggs — and brandy! Indeed, Louis’s taste for alcohol became something of a local legend, with some newspapers labelling him a “lush.” (Other reports claimed that his annual brandy consumption was only a modest two bottles, doled out daily in small dollops.)

Louis reportedly had an extensive vocabulary of swear words that would make most humans blush. But where did he pick it up? After all, Wilson was described as both refined and genteel. “I’ve heard some of the things that bloomin’ bird says now and again,” an elderly Victoria tradesman told Life magazine in 1963, “and what I can say is you can bet your ruddy home he never learned it from Miss Wilson. She was a proper and kindly lady.”

In 1917, when Wilson was forty, her mother Kitty died. For many years, Wilson’s life revolved around her domineering, aging father, with the two of them living in their mansion secluded from society. For respite she visited her birds upstairs twice daily.

It was only after her father’s death in 1934 that Wilson began to venture out in public. She hosted small, intimate dinner parties at the city’s venerable Empress Hotel, which were patronized by high society, and went on occasional shopping expeditions, wearing a long sable coat in cold weather. Otherwise, her life was very quiet; she never had company and spent most of her time at the White House with her birds and her cat, Fagan.

“She continued to fill her closets with tasteful and expensive clothes, but she rarely wore them,” Laura Langston wrote in “Fame came after parrot lady died,” a 1988 Victoria Times Colonist article. “Infrequently, she attended an afternoon tea. She was a quiet, soft-spoken woman, always properly dressed and usually seen standing off to the side or in a corner.” By this time, Wilson was in her late fifties and was thinking increasingly about her beloved Louis’s future — and the possibility he would outlive her.

When Wilson died in 1949, she left a house full of antiques, closets filled with clothing and hats, drawers of gloves, and an estate of nearly half a million dollars (equivalent to $5.5 million today). Much of it — $340,000 — went to charities, including the Red Cross, the Royal Jubilee and Queen Alexandra hospitals, and the BC Protestant Orphanage. Self-effacingly, the money was donated in her father’s name, not hers.

She left her second-tier birds with ample provisions for their maintenance but far less than for her treasured Louis. Dear old Louis was numero uno. She earmarked $60,000 ($665,365 today) for his care. The will even provided Louis with his own human servant — Wilson’s gardener, Yue Wah Wong, who was kept on staff and paid $250 a month, a goodly sum equivalent to $2,700 today, to look after the bird. Louis reportedly pined for his deceased mistress and could be heard calling "Miss Wilson, Miss Wilson, I want some water."

As Victoria Jane Wilson had lived in seclusion in her mansion, the rest of downtown Victoria slowly built up around her. Gradually, many of the fine old homes of similar vintage to hers were torn down to make way for high-rises.

After her death, her mansion and spacious grounds were sold to Douglas Abrams, an apartment developer, who announced his intention to demolish the house and develop the property into a modern, multiple-unit, high-rise apartment complex. But he had overlooked Louis. Tucked away in Victoria’s will was an escrow clause stipulating that Louis must live out his days in the home — and that under no circumstances must his environment be disturbed. This meant that the White House, including its then-attached aviary, heated from the same furnace system as the house, had to remain standing until Louis dropped dead.

At the time of Wilson’s death, the parrot was believed to be eighty-six. Calculating the actuarial odds, Abrams figured Louis’s days were numbered.

“He subdivided the existing house into six apartments and sat down to wait out the old bird,” Life magazine reported in 1963. “But Louis callously recovered from the pain of his mistress’s passing and, to Abrams’s rueful astonishment, seemed to take a new lease on life.”

Unfortunately for Abrams, Louis was one of the rarae aves (rare birds) with a longer-than-average lifespan.

Like the reclusive Hollywood star Greta Garbo, Louis wanted to be left alone by the public. He apparently disliked having his picture taken — flashbulbs put him in a foul mood. Thankfully, he had very few visitors. Each year, a representative of the Royal Jubilee Hospital looked in to see if Louis was still ticking. From time to time, a member of the law firm administering Wilson’s estate dropped by for the same purpose.

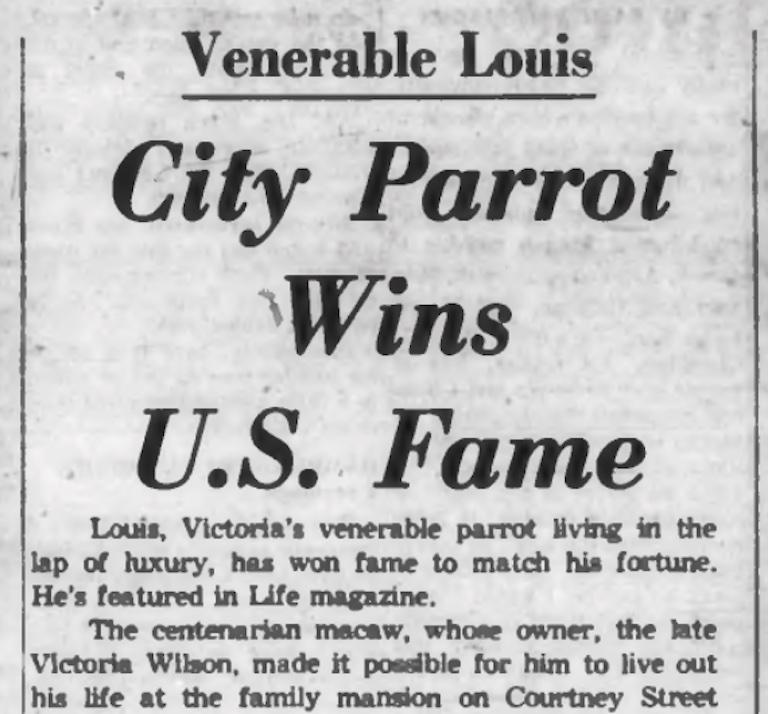

Abrams waited nine years for the parrot to croak before giving up in 1958. He sold the property to two Victoria businessmen who also claimed that they were willing to wait out Louis.

As the years rolled by, Louis outlived all of Wilson’s other birds. Meanwhile, the media continued to flock to the story. A spate of tongue-in-cheek newspaper articles were published, including the 1959 Calgary Herald story “Hard-Drinking Parrot Stymies Progress” and a Vancouver Sun opus published in 1961, “100 Year Old Parrot Still Soaks Up Brandy in Victoria.” The latter tale described a visitor’s effort to ascertain, by peeking through the mansion’s windows, whether the bird was still breathing.

Louis’s lifespan was a matter of supreme importance to a pair of local organizations. Wilson’s will decreed that, upon Louis’s death, the residue of his inheritance was to go to the Royal Jubilee Hospital and the Red Cross. The will also disqualified any beneficiary who contested it — something that greatly displeased A.C. Wurtele, the Royal Jubilee’s board chairman.

“It seems to me that people are more important than parrots and Louis might well be turned over to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals,” Wurtele said in a December 1966 interview. “This money is being wasted. The estate is being eroded by legal fees, and I am afraid there will be nothing left.”

In 1963, Life magazine writer Russell Sackett travelled to Victoria to check in on the bird’s well-being. He had first written about Louis in the late 1950s. In his 1963 follow-up, he recalled that earlier eventful encounter: “I first met Louis in 1957; I wanted to see the noted squatter. I was reassured by a view of Louis, brilliant blue and yellow, looking splendidly indestructible even through a dusty, heavily screened window of his private house, where he was doing a headstand on his perch.” Sackett had returned to Victoria in 1963 to investigate the bird’s welfare. Checking in at the Empress Hotel, the reporter met a long-time Victoria resident who wondered whether Louis actually was dead and had been replaced by a doppelgänger.

Sackett eventually spoke by telephone to Wong, the bird’s caretaker, who invited the reporter to come to the mansion, look through the window, and see for himself. Sackett described what happened next: “Feeling unsure and jittery as I squeaked through the gate, [I] walked to the window, shaded my eyes and tentatively called, ‘Louis?’ There was a shadowy movement far back in the birdhouse, and suddenly there was Louis, jaunty and resplendent as ever, sidestepping deliberately along his perch toward the window. ‘Wong?’ he rasped, eyeing me accusingly.”

Louis lived at the mansion for another three years. But his lengthy occupancy was nearing its end. In 1966, the law firm that managed Victoria Jane Wilson’s estate decided that it was too costly to keep him in the large house, which had fallen into decay. After some discussion, lifelong arrangements were made for Louis to be cared for by Wong and his family at their premises, a modest abode. With the macaw at long last having flown the coop, builders were free to develop the estate.

In 1969, Canadian Magazine published “The Bird Who Has It Made,” which described how Louis continued to live a privileged, pampered life. Wong died soon after taking the bird in, but his family continued to care for the parrot in the grand manner to which he was accustomed. The exact date of Louis’s death is unknown; some say that he died a few years after Wong, but others claim that he held on until 1985, when he would have been about 115 years old.

While the bird is gone, his legend lives on. In 1975, the Chateau Victoria Hotel & Suites was built near the former White House site, complete with a top-floor restaurant named the Parrot House after you-know-who.

And today, Victoria’s Hallmark Heritage Society’s highest prize for heritage preservation is called, you guessed it, the Louis Award, in honour of the parrot who for years fought the forces of progress — and won.

GLIDE AND RIDE

Louis the parrot is likely the first bird to ever “own” an electric car. Victoria Jane Wilson asked her father, Keith Wilson, to buy her the vehicle, a luxury Hupp-Yeats electric automobile, so that she could take her pet parrot for short drives.

The Hupp-Yeats was produced in Detroit from 1911 to 1916 and employed a then new technology, the Exide Hycap battery, for propulsion. The vehicle featured a glass roof, lamps on each side of the upper hood, and a holder for flowers behind the driver’s seat.

Unfortunately, Louis reportedly didn’t like the car’s noise, and the auto was put into storage after just a few outings. Following Victoria Jane Wilson’s death, the vehicle was purchased in 1959 by Stan Reynolds, an Alberta vehicle collector.

The Hupp-Yeats is today displayed in the Reynolds-Alberta Museum in Wetaskiwin, Alberta. The museum traces the mechanization of transportation, aviation, agriculture, and industry from the 1890s to the present. Museum curator Justin Cuffe said the car was found in a garage behind a sealed wall in Wilson’s mansion. He noted that Reynolds had to take great care “to delicately remove it without bothering Miss Wilson’s pet parrot Louis, who had his aviary set up in front of the garage.” When the car was finally extracted, it had less than 160 kilometres on the odometer.

— Susan Goldenberg

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!