Controversy and Compromise over the Manitoba Schools Question

When Manitobans cast their vote on July 11, 1888, they could not have imagined that their selection would propel Manitoba into the national spotlight, drastically alter the province’s future, and create a controversy that would become a standard entry in history textbooks for years to come.

The Lead-up

In 1887, longtime premier John Norquay resigned after a dispute with Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Norquay, responding to an increasing pressure from Manitobans to end the CPR monopoly in the area, had ordered the construction of a rail line to connect Winnipeg with the U.S. border. Macdonald retaliated by withholding a previously promised land transfer, leaving the province with a deficit of $256,000 and causing the Norquay government’s collapse. The Liberal Party, under the leadership of Thomas Greenway, stepped in to govern.

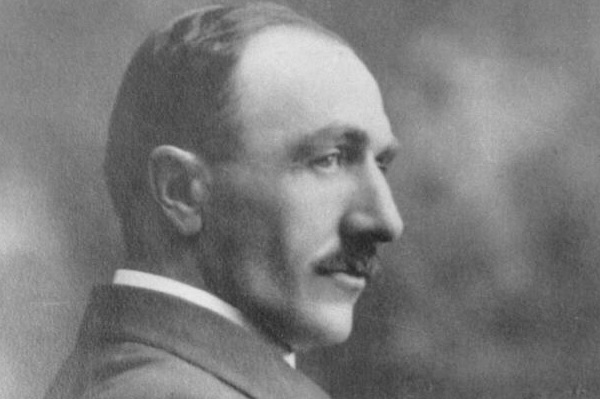

Once in power, Greenway continued Norquay’s work, fighting against Ottawa for more provincial rights and the end of the CPR monopoly. It was more timing than Greenway’s skill that caused Prime Minster Macdonald and the CPR to reach an agreement to end the monopoly. Nevertheless, Greenway became a champion of provincial rights amongst Manitobans. With his popularity secure, Greenway took the opportunity to call an election, winning 33 of 38 seats. Manitobans elected their first Liberal Premier and the man who was going to create controversy and history with the Manitoba Schools Question.

The Manitoba Schools Question

When the province was created under the Manitoba Act of 1870, the population was divided almost equally between French-speaking Catholics and English-speaking Protestants. As such, a dual school system was created, with public funds allotted to both Catholic- and Protestant-run schools. However, by the time Greenway was in power, Manitoba was increasingly inhabited by English-speaking Protestants, with many — like Greenway himself — coming from Ontario. As the demographics shifted, cultural and religious tensions increased.

In 1890, Greenway’s government made changes to the education system that were long feared by French Catholics. He abolished the dual system and set up a non-denominational school system. Not only would Catholic schools no longer receive public funding, but parents choosing a Catholic education for their children would still have to pay taxes to the public system. The legislation dictated that schools would be run in English and removed bilingual provisions of the Manitoba Act, making English the only language used in the courts and government. Manitoba’s French population felt their language and culture were being threatened and that their rights guaranteed under the Manitoba Act violated.

The issue quickly moved beyond Manitoba’s borders and engulfed the entire country. It divided French and English Canadians, created tension between Catholics and non-Catholics and called into question the role of the provincial and federal government in education.

A series of court challenges against the new legislation were launched by Manitoba’s Irish Catholics who felt that their constitutional rights were being denied. An 1892 ruling by the Privy Council ruled that new legislation was valid, but another ruling in 1895 held that the federal government could disallow the legislation and restore funding to the denominational schools. The federal government, reluctant to take any bold moves in the matter, was forced to get involved.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Eyes on the Federal Stage

In 1896, the Federal Conservative government, led by MacKenzie Bowell — the third leader to replace John A. Macdonald after his death in 1891 — voiced his support of Manitoba’s French-Catholics and legislation to restore their rights. The issue even cut through the Conservative party, and cabinet members forced Bowell to resign. Charles Tupper took up the Conservative leadership and introduced another remedial bill. It was opposed by the Liberals, led by Wilfred Laurier, and Tupper was forced to abandon the bill and call an election — less than two months into his term as Prime Minister.

The Federal election of 1896 was fought largely on the Manitoba Schools Question. With the Conservative Party still divided over the issue, the party was viewed as weak and disorganized and faced much criticism. Laurier’s Liberals, who took a passive position on the issue, won the most seats and defeated the Conservatives.

The Compromise

Laurier’s “middle-of-the-road” position on the issue led to the Laurier-Greenway Compromise within the first year of his term. Under the compromise, Catholic teachers could be employed in schools with forty or more Catholic children and, if requested by enough families, religious instruction could be permitted for half an hour a day. Where there were enough students, French could be used in addition to English.

The Compromise was mostly a concession for French-Catholics. The rights granted were done so on an individual basis, and provided no protection for their language, religion or culture as a whole. The bitter controversy is still remembered as one of the most important fights, and losses, for French-language rights in Canada.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

More Provincial Game-Changers

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!