Canada’s Last Hangings

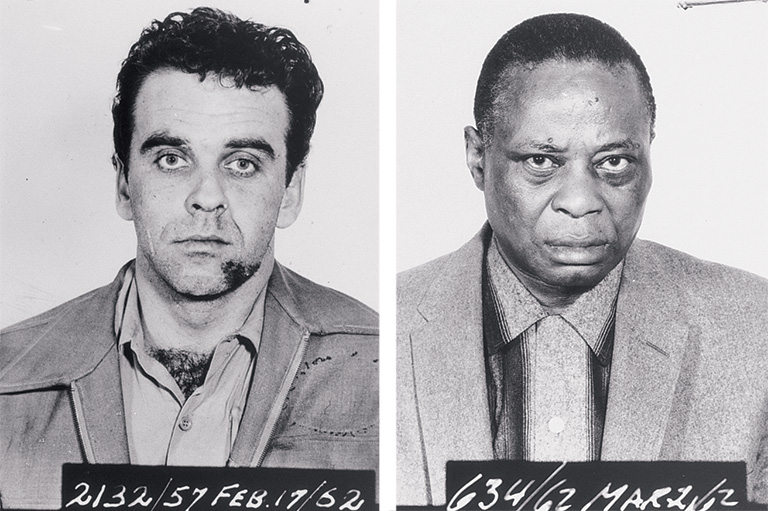

Early in the morning of December 10, 1962, Arthur Lucas and Ronald Turpin still hoped they could avoid being marched to their deaths at midnight. Convicted of murder in separate cases, they were sentenced to hang at the Don Jail in Toronto. But there was reason to be optimistic. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker had commuted most court-imposed death sentences to life imprisonment, and the cabinet’s decision on a last-minute appeal was pending. Many in Toronto’s legal, academic, and religious communities were lobbying intensely for the government to step in to reverse the judgment of the courts.

Shortly after noon, however, the news arrived: There would be no eleventh-hour reprieve. The government decided that the hangings would go ahead. Inside the century-old brick-and-stone jail on the east shore of the Don River, the two condemned inmates were reportedly calm in their final hours. Shortly before midnight, they were led to the small converted washroom that housed the gallows. Two dozen men had been hanged in the same room over the years, ever since officials had moved executions indoors to prevent them from turning into public spectacles. With their hands bound behind their backs and manacles on their feet, wearing jail-issued blue pants and grey shirts, Lucas and Turpin stood back-to-back as the hangman slipped a noose over each of their hooded heads. At two minutes after midnight, the hangman sprang the wooden trap door. They were officially declared dead sixteen minutes later. Their bodies were driven across town to Prospect Cemetery, where they were buried side by side in unmarked graves.

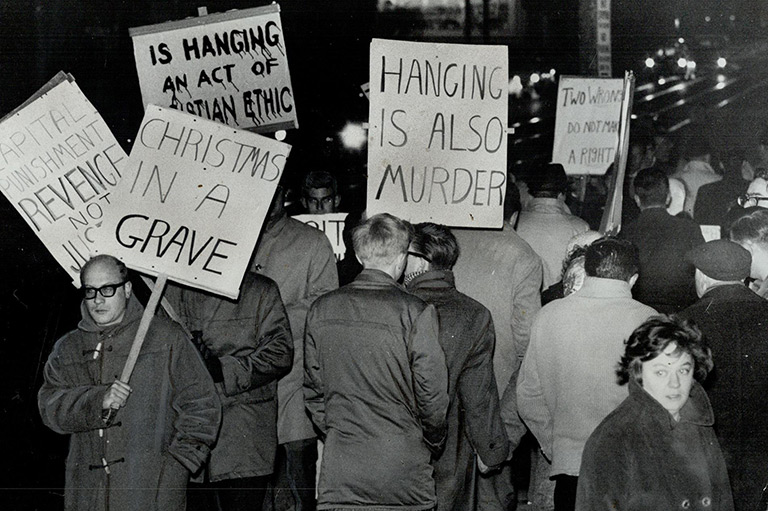

In the cutting wind and freezing temperature outside the jail, demonstrators had been picketing for hours. When jail officials posted a notice of the hangings at 12:30 a.m., the crowd surged forward shouting “murderers” and “killers.” Police had to call for motorcycle backup, and there were a few arrests before the crowd eventually dispersed. Meanwhile, members of the Don Heights Unitarian Congregation were holding a death-watch service in their church. “This ugly thing must be fought,” said Rev. Franklin Chidsey. “I refuse to accept the principle that there is anything such as a legal killing.”

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

The demonstrators couldn’t have known it, but the fifty-four-year-old Lucas and twenty-nine-year-old Turpin would be the last people executed in Canada.

The debate over capital punishment in Canada was particularly intense in the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps the most powerful argument for abolishing the death penalty lay in the question: What if the convicted person was innocent of the crime? A wrongful conviction might be discovered years later, but if the accused had already been executed, there would be no correcting the injustice. Between 1956 and 1966, four Canadian journalists — Betty Lee, Jacques Hébert, J.E. Belliveau, and Isabel LeBourdais — played a central role in driving this point home to the Canadian public. Their investigative work cast doubt on the criminal convictions of three people who had all been sentenced to hang. In so doing, they laid the groundwork for the eventual elimination of capital punishment in Canada.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement