The Last Battle of Seven Oaks

Grantown, Manitoba, 1821

The boys were fighting as usual.

Whenever enough families got together, and enough boys had nothing to do for a while, the battle began.

This time the families were gathered to celebrate Pierre’s grandmother’s birthday. All the aunts, uncles and cousins who could travel to Grantown had made the trip. While the grownups talked and the pig was cooking on the spit, the boys went to battle.

The field behind the barn was renamed La Grenouillère and the boys took sides. Pierre’s father, Paul, leaned on the fence and watched them.

“I get to be Cuthbert Grant!” yelled Pierre.

“You were Grant last time. This time you have to be Governor Semple,” said Francis.

“Okay, but I want to be a Nor’Wester next time.”

“I’ve been a Bayman twice,” piped up Michel. “I get to be a Nor’Wester this time.”

“You can be François Boucher. Now go talk to Semple like Grant ordered!” said Francis.

The boys stood in two uneven groups — more Nor’Westers than Baymen — with Michel leading one side and Pierre the other.

“Wait! I don’t have a horse,” protested Michel.

Pierre ran to the fence and grabbed two hay rakes. He gave one to Michel.

“Now you do!” said Pierre. He and Michel mounted their imaginary horses, scowling at each other as they became their characters, riding into battle at the head of their forces.

Michel/Boucher yelled. “What do you want?”

“What do you want?” Pierre/Semple yelled back.

“We want our fort!”

“Then, go to your fort!”

“Why did you destroy our fort, you rascal?” yelled Michel.

Pierre pretended to grab the reins of Michel’s horse. That was it! All of a sudden, everyone was pointing an imaginary gun and yelling “bang!” In moments, most of the Baymen were sprawled on the ground. The Nor’Westers whooped, “Victoire, victoire, la victoire de la Grenouillière!”

In the middle of the cheering, Pierre saw his father leaning against the fence, holding a piece of paper. “That’s how it went, right Papa?”

The other boys sprang back to life or stopped yelling. Everyone waited for Paul’s answer. After all, he’d known a man who had actually been at the battle five years ago.

Paul nodded. “Oui, that’s how it went.” He looked at the boys. “But can anyone tell me why the Baymen and the Nor’Westers were fighting?”

“It was about food. It was about our pemmican,” said Francis. “The Baymen took food from our trading post on the Assiniboine. And they stopped us sending food to the other Nor’Westers who were hunting for furs. They gave our food to the settlers, so our men didn’t have anything to eat. No food meant they couldn’t hunt.”

“Then Governor Semple came and tore down our fort and kicked us all out of our homes,” added Michel. “And he stopped us from using the river to get food to our men.”

The boys nodded at the familiar story.

“Do you remember what happened after the battle?” asked Paul.

“Lots of people got arrested and sent to Montreal, but they’re all home again,” said Pierre.

“So many others died, though, and never made it home,” said Paul, almost to himself.

The boys nodded solemnly. They’d heard stories of forts being attacked and canoes ambushed in the feud between the Hudson’s Bay men and the Nor’Westers. They’d all worried when their fathers and brothers were away from home.

Paul folded and unfolded the paper he was holding.

“What’s that, Papa?” asked Pierre. They hardly ever got letters, and he was afraid that it was bad news.

“What’s it say?” asked Pierre.

“It says that the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company have joined together. It’s all over.”

“We’ve been fighting all this time and didn’t win?” asked Pierre.

“In a battle only one side can win. But when there is peace, we can all win,” said his father. “We can work and raise our families.”

Pierre hung his head and kicked at the grass.

“What’s the matter?” his father asked.

“It won’t be as much fun playing La Grenouillère anymore,” said Pierre.

“You’ll find other games,” said Paul. “For now, why don’t you all concentrate on eating that pig that’s been roasting all day?”

The boys jumped over and ran to get their plates filled. Paul tore the letter into little pieces and let them float away on the wind. He turned and looked at his family. Instead of wondering when the next attack would come, they were happy and safe. They had a future. Peace is better, he thought.

Lord Selkirk, who had a lot of money invested in the Hudson’s Bay Company, encouraged Scottish settlers to come to the Red River settlement in the area that is now Winnipeg.

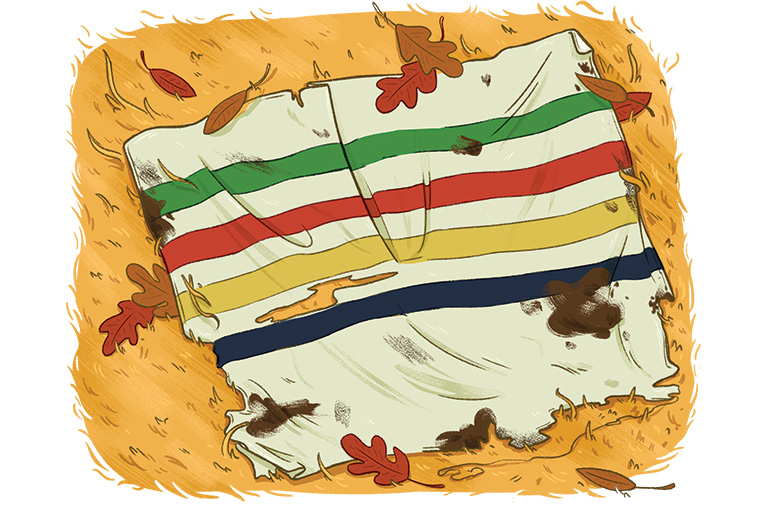

In 1815, many settlers arrived, but they were too late to plant any crops. Miles Macdonell, a Bayman in charge of the Red River settlement, seized pemmican supplies from the Nor’Westers to feed the settlers. He then passed the Pemmican Proclamation banning the sale of pemmican to the Nor’Westers.

Robert Semple, the governor of the Hudson’s Bay settlement on the Red River, tore down the Nor’Westers’ most important trading post, Fort Gibraltar.

On June 19, 1816, Semple and a group of about 25 Baymen left the fort at Seven Oaks to confront General Grant and 61 Nor’Westers and Métis. The Métis called this area Plaine des Grenouilles or Frog Plain. In the fight, 21 Baymen including Semple, and one Métis, were killed.

The head of the North West Company and many others were sent to Montreal for trial, but the investigators said neither side could be faulted completely and freed the men.

Over the next five years, the violence between the two companies grew worse. In 1820, Lord Selkirk died. The two companies merged the next year.

Our story is set in Grantown, a village just west of Winnipeg that was named after Cuthbert Grant. It is now called St. François-Xavier. There is a monument in downtown Winnipeg near the site of the battle.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive features both English and French versions of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids — 3 digital issues per year for as low as $13.99. Tariff-exempt!