War Games

In an age when tech can game out gazillions of options in a split second, it’s arresting to take in the very real, often very analog, military simulations at the heart of the War Games exhibition at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. Arresting, even when those simulations involved model battleships being pushed around a floor while observers made strategic choices based on what they could see through a small opening in a sheet of plywood.

The relatively unknown work of the Western Atlantic Tactical Unit (WATU) is among the most directly war-oriented of the pursuits featured in War Games, which runs until Dec. 31, 2023. Staffed mostly by women from Britain’s Royal Naval Service, or Wrens, WATU involved simulating the movements of Allied ship convoys across the ocean, as well as considering likely German U-boat tactics.

Over the unit’s three-year history, officers, including Canadians, suggested strategies the Wrens carried out, drawing movements in chalk on the floor. The Wrens also offered suggestions and pointed out shortcomings in the Navy’s thinking about U-boat manoeuvres. By trying out different approaches in an environment where lives weren’t on the line, the unit developed better ways to anticipate and counter attacks. (The wonder of finding out about WATU’s innovative, life-saving work is dampened by the unsurprising revelation that while men involved in the unit received medals for their work, none of the women did.)

The exhibition contains other instances of games used by various military forces to prepare for battle. A beautifully crafted wooden chest contains the 1,500-plus pieces of the appropriately titled British creation of the 1880s, The Game of War. Originating with the Prussian (of course) game Kriegspiel in the mid-1800s, these games were a low-stakes way to train officers to think strategically. Indeed, the exhibition notes, Canada ordered several sets of The Game of War as the all-too-real First World War began to look inevitable.

The seed for the exhibition was planted more than a decade ago, says the war museum’s post-1945 historian, Andrew Burtch. Young visitors seemed to know the equipment on display at the museum in great detail, presumably because they’d encountered them in video games. Himself a keen player of video and tabletop games, Burtch had been working on the best way to explore the subject until a connection to a collector of war games gave it new energy.

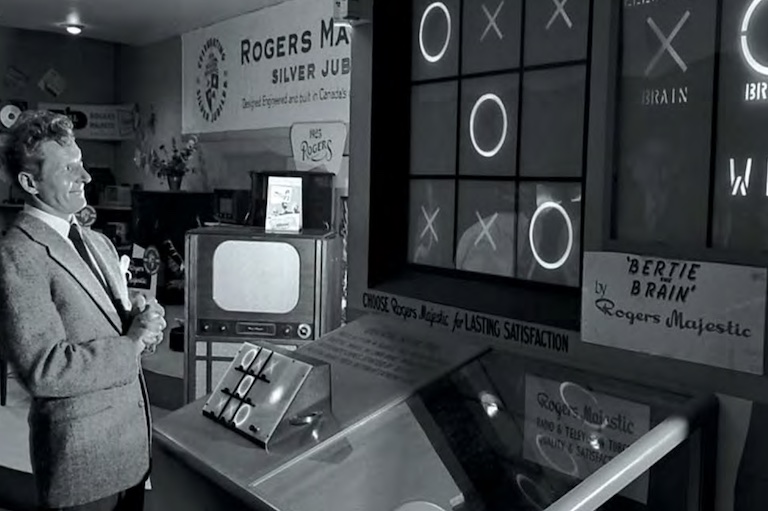

War Games takes visitors through five chronological zones, from ancient times through the world wars and the Cold War to modern military challenges including terrorism, refugee crises, climate change and, yes, pandemics. (A fascinating photo shows the Canadian military personnel charged with distributing COVID-19 vaccines gathered on and around a giant floor map and tokens representing transportation options.) There are stops along the way for toy soldiers, early alien-attack video games and role-playing games such as Dungeons and Dragons.

The exhibition is both thoughtful and thought-provoking, which isn’t an easy line to walk given that some games clearly glorify war for propagandistic purposes or treat conflict as an amusing backdrop. One game is built around First World War trench life, another around maintaining blackout conditions in Britain during the Second World War, while a Cold War-era set treats miniature missiles as toys. “There are very complex connections between what we do for fun and the very serious and deadly business of preparing for and carrying out war. We play games about war because they matter to us,” Burtch says.

The exhibition avoids the lazy approach—showcasing a bunch of white guys—drawing instead on an admirable diversity of sources and interviewees. A powerful video features two Canadian veterans of the Afghan war who are also gamers explaining that video games can’t possibly capture the reality of heat, dust, heavy equipment, fatigue, a lack of situational knowledge or a million other stresses of actual battle. Helmet camera footage of real combat conditions provides a sobering contrast to the sterility of video games attempting to approximate war. A nearby panel describes research into the potential for some video games, particularly those born in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks in the United States, to foment racism.

Players of games like Risk, Pandemic and Settlers of Catan will see their favourites showcased in a new light. And yes, visitors have a chance to play several games themselves, as well as to reflect on the war games they enjoy. “I hope the exhibition helps people to be reflective of the media they’re consuming,” Burtch says.

The exhibition is enlightening and entertaining, but never muddies its focus with historical gee-whizzery. A visitor leaves realizing that while war games can be a pleasant pastime or a valuable intellectual exercise, war itself is horror.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.