The Many Wars of Doug Sam

In early July 1944, my grandmother learned from the Canadian government that her son Kam Len Douglas Sam, my father, had been shot down over northern France on a bombing mission and presumed dead.

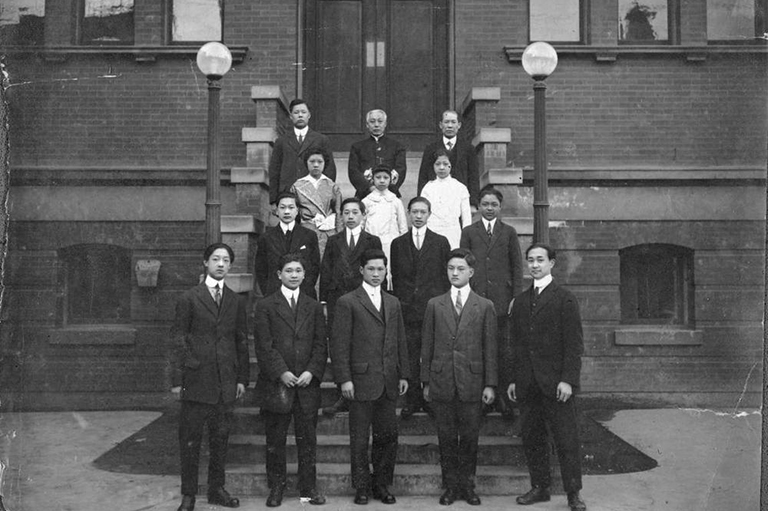

He was a third-generation Chinese Canadian, born in Victoria in 1918, and a pilot officer with the Royal Canadian Air Force. Church services eulogized him and Victoria newspapers paid editorial tribute to a hometown boy from Chinatown who made the supreme sacrifice. My great-grandmother, though a devout Anglican, went to the Chinese temple in Victoria and lit incense. The joss sticks told her that her grandson was not dead.

The joss sticks were correct. Sam had parachuted safely. He landed only 180 metres from a Luftwaffe base but was able to contact the French underground.

His family would not learn he was alive for many months. The French underground and MI9, the section of British Military Intelligence charged with aiding resistance fighters in Nazi-controlled Europe, maintained the ruse that my father had died in his Halifax bomber.

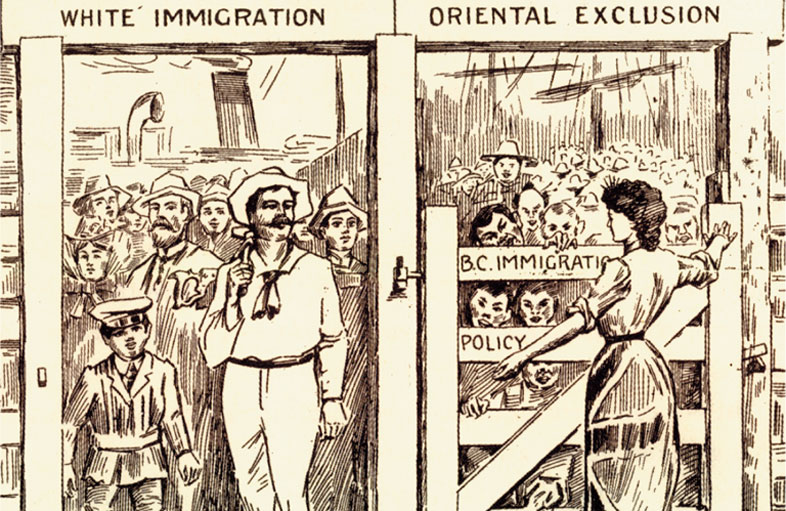

He had been rejected from the RCAF in 1941 for not being Caucasian. He got in a year later when the government removed the racial clause in entry rules, and his Chinese ancestry proved to be an asset. He was to stay in France to coordinate the escapes of other Allied airmen. Resistance members provided him with clothing and forged papers to identify him as an Asian student trapped in France by the German occupation.

Through the summer and early fall of 1944 he aided the resistance in northern France, bluffing his way out of two Gestapo round-ups with the high-school French he had learned in Victoria. He witnessed the ambush of German supply convoys, the elimination of Gestapo agents and French collaborators and the systematic roundup and shipment to death camps of French Jews and Gypsies.

In September 1944, the commander of an American tank entering Rheims in advance of the U.S. Third Army was surprised to receive maps of street plans and deployment of German forces in the city from the Chinese Canadian in charge of the resistance force.

My father had flown in 28 terrifying raids over Fortress Europe in 1943 and 1944, including a mission over Nuremberg that saw 94 Allied bombers go down and one over Berlin that lost 73. A street barricade in Rheims, however, was to be his last fight of the Second World War. He later said that it was the first battle that totally frightened him, because it was the first he had fought on the ground. Using air-dropped weapons, he and his underground forces engaged German troops in a vicious fire-fight, successfully fending off three ferocious attacks until U.S. troops entered the city and forced the enemy to capitulate.

Days later, my father was in London. He sent a telegram to my grandmother telling her he was alive and well. She cried happily. My great-grandmother was unsurprised; the joss sticks had told her he was safe.

The war in the air and the war on the ground of World War Two were not my father’s last. While the Korean War occupied the minds of most Canadians in the early 1950s, he was seconded to the Royal Air Force to serve as a counter-insurgency specialist in the Malay States. The British were fighting a jungle war with Chinese, Malaysian and Indian communists.

My father interrogated more than 300 prisoners, making good use of his fluent Cantonese and Mandarin. He served under Sir Maurice Oldfield, the late British master spy said to have been the model for novelist John le Carre’s fictional character George Smiley.

In 1967, after 25 years of continuous service, including stints in London and Washington, my father retired from the RCAF with the rank of squadron leader, the most decorated Chinese Canadian ever. Included among his honours was the Croix de Guerre, silver star, awarded by the French government.

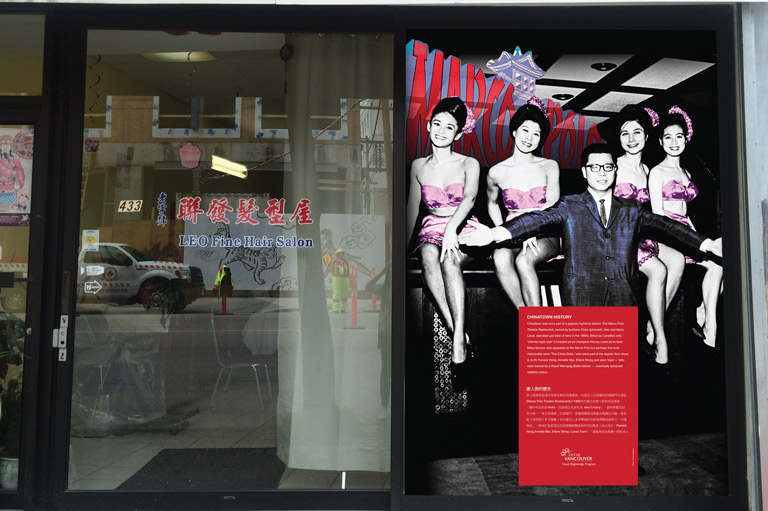

Retirement from active military duty did not end his public service. Joining the Department of Employment and Immigration in 1967 as an intelligence analyst, he rose to become the department’s chief of immigration intelligence for the British Columbia-Yukon region at a time when Asian youth gangs were a growing presence. Once, my father and some local detectives were in a Vancouver restaurant, observing the noisy antics of some Chinese gang members. He went over and had a quiet little chat with them. The gang members looked around at the detectives, mouths agape, then stood up and immediately left.

When my father rejoined his party, he was asked, “How did you manage to get them to do that?” Sam laughingly said, “I just told them who I was and that if they did not quiet down, I was going to hold an immigration meeting right then and there, and they would all be gone first thing in the morning.”

Kam Len Douglas Sam, the eldest of nine children born to Mr. and Mrs. Sam Wing Wo, who immigrated to Victoria from Yin Ping in the vicinity of Canton, China, retired from his final war in 1983. He died in 1989 at age 71.

When he was a teenager at Victoria High School, someone inscribed in his yearbook, “Doug has aspirations to become the Chinese Lindbergh.” I think that from the time he was old enough to see the blue sky, he wanted to grasp it; he wanted to fly. And so he did.

More about Doug Sam

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement