The Darkest Nights

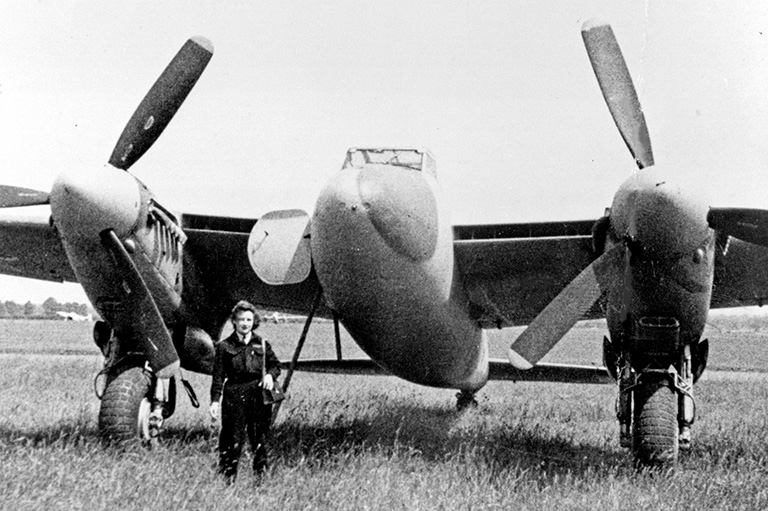

Joe Halloran, a young Canadian Bomb aimer with Royal Air Force 622 Squadron, climbed into his Lancaster bomber as a cool January evening settled over RAF Mildenhall, about 130 kilometres northeast of London, England. After more than a year of flight training, the bomb aimer and his crew ascended into the night for their first operation over enemy territory. One of four brothers, all serving in the armed forces, Halloran reached down for the three chocolate bars that had been provided to him by the local women’s auxiliary. Not knowing what the night ahead would bring, he quickly ate all three, lest he be shot down or killed and the candy bars go to waste. Ahead of him lay the first in a series of harrowing missions over Germany during the most dangerous period of the war for bomber crews.

Conceived over the summer of 1943, the Battle of Berlin was planned as an extended campaign of bomber raids against the German capital city and other important targets. RAF Bomber Command and its commander, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, viewed the campaign as an opportunity to deal a significant blow to the enemy and to potentially knock the German capital out of the war. The campaign would build on a growing number of experienced crews, technological advances, and advanced four-engine heavy bombers, but it would be costly in terms of aircraft and the lives of aircrew.

At the time, Bomber Command — the strategic command that controlled all bomber operations undertaken by the Royal Air Force and the Royal Canadian Air Force — could call on an active strength of around eight hundred heavy four-engine bombers on any given night. The bombers were organized into six bomber groups, with each group consisting of around a dozen bomber squadrons and each squadron fielding between twenty and thirty aircraft. One of the groups — No. 6 RCAF Group — was unique in that, unlike the other RAF groups, it was led and organized by Canadian officers, although RCAF aircrew served throughout the RAF and RCAF squadrons.

The campaign began in late November 1943 and was well underway when Halloran and his crew took off for the city of Magdeburg, Germany, on the night of January 20, 1944. At eight minutes after 11:00 p.m. they dropped their payload of bombs from twenty thousand feet (six thousand metres). Through the thick cloud cover they could see many fires below, before they returned safely to Mildenhall just before 3:00 a.m

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Sid Philp, an RCAF navigator, was also making his maiden mission over Germany that night — but his sortie did not go as smoothly as Halloran’s. He recalled later in a letter to historian David Bashow that the “planned route took us east across the North Sea, then a feint towards Berlin before turning south to the target.” RAF planners hoped that by feinting towards Berlin they could confuse German anti-aircraft gunners and night fighters, the specially equipped single-engine and two-engine aircraft designed to track down Allied airplanes in the night. But, Philp recalled, “The low murmurs from the veteran crews at briefing implied that this was not going to be a piece of cake.”

Flying over Magdeburg, Philp stepped away from his navigation station to look at the target area. From the aircraft window he saw lights in all directions — flares illuminating the bomber stream to make them easier prey for night fighters, a steady stream of flak bursts ahead, bombs exploding on the ground, fires burning below, and flak tracer bullets slowly rising to meet the bombers. “It was beautiful and, at the same time, a frightening sight,” he recalled. “I decided I had had enough beauty for one night and I crawled back down to my enclosed ‘office.’ I never again looked out at the target area.”

Philp’s aircraft was caught by a night fighter after releasing its bombs over the city. The pilot took evasive action by performing a corkscrew dive, the usual method for bombers to escape from searchlights or night fighters, and initially avoided significant damage. However, as the bomber reached the west coast of Europe it was lit up by searchlights and hit by heavy flak. “One piece [of flak] went right through the rear turret without touching the gunner; another piece ripped out some wiring next to the engineer; a third piece tore a ridge in the outside of the wireless operator’s boot; and yet another spent piece landed on my desk,” recalled Philp. Heavily damaged and leaking fuel, the bomber somehow managed to land at an emergency airfield in southeast England. A review the next morning found more than eighty-five holes in the aircraft.

Philp and Halloran were each fortunate to survive their first mission against a target deep in German territory. Of the 648 aircraft attacking Magdeburg, 57 were lost — an extremely high loss rate of 8.8 per cent. Aircrews were often at their most vulnerable during their first few missions, when they lacked combat experience. “I do not recall being frightened at any time while in the air,” Philp said of the Magdeburg raid. “However, once out of the kite and into a bus, I started to shake as though I had a severe chill. The shaking kept up until I arrived in the debriefing room and some clever soul, seeing my condition, handed me a mug of coffee with a very stiff shot of rum in it.”

Survival in the air war meant utilizing the months of training that had prepared the flyers as well as possible for their first mission. From across the British Empire young aircrew were pouring into Canada during this time to participate in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, one of the RCAF’s most important contributions to the war effort and one of its most critical activities during its hundred-year history. All told, more than 130,000 men, as well as thousands of women, were trained to serve in air and ground crews through the program. More than seventeen thousand women served in the RCAF Women’s Division, both in Canada and overseas with No. 6 RCAF Group.

Halloran’s in-flight training took place at No. 4 Bombing and Gunnery school in Fingal, Ontario. Flying over the shores of Lake Erie, he learned basic air gunnery and bomb-aiming skills, carefully recording in his logbook the decreasing margin of error on his practice bomb drops. In April 1943, he completed his air bombers course at No. 9 Air Observer School in Quebec before proceeding overseas.

In England, aircrew continued their training and gained additional experience, often learning first-hand from the small number of experienced pilots, navigators, flight engineers, bomb aimers, wireless operators, and machine gunners who had completed a thirty-mission tour of duty. Perhaps the most important part of the training was forming a new bomber crew, a process that was far more informal than one might imagine for a military operation. Howard Hewer, a Canadian wireless operator, recounted that all the newly qualified crew were hurried into a large mess hall and left to their own devices to build out a bomber crew. “We’ve found that it’s best for you to sort yourselves out, and pick whom you wish to finish the course with,” Hewer recalled his squadron leader explaining. “I’ll leave you to it then. Good luck.”

Hewer focused on finding a good pilot, which seemed to him the surest way to survive the war. Joe Halloran teamed up with Jack Lunn, a pilot who grew up watching planes fly over his family farm near Gainsborough, England. They completed their training together before joining 622 Squadron based at RAF Mildenhall in late 1943. A week after their first mission to Magdeburg in January 1944, they would be called upon to attack Berlin.

Advertisement

Roger Coulombe, a pilot from Montmagny, Quebec, knew all too well the challenges that Berlin presented to the attackers. Coulombe, a pilot with RCAF 426 “Thunderbird” Squadron, had already participated in nine raids on the German capital and would complete twelve by the end of March, earning him the nickname “the Berlin Kid.” “Most of our raids on Berlin were done during the fall and winter when the period of darkness was the longest,” explained Coulombe. The eight-hour flight from England to Berlin through the long winter night was a perilous journey for bomber crews. Each member had to contribute to a successful mission, constantly scanning the night sky for enemy aircraft, taking careful navigational readings, sending and receiving wireless messages, and guiding the aircraft to the target. Crews were only illuminated by the enemy searchlights, the fires below, or, on particularly bad nights, the light of the moon. They often flew in –40°C temperatures, stocked with just the right amount of fuel to get to the target and home.

In addition, the city of Berlin was heavily guarded by extensive fortifications. “The Big City,” recalled Coulombe in a letter to historian David Bashow, “was protected by a tremendous quantity of anti-aircraft guns ... [and] there was a terrific quantity of searchlights trying to cone and isolate a bomber if the sky was not completely overcast. This combination of searchlights and always intense flak was terrifying enough.” In addition to the ground defences, German night fighters prowled in and around the bomber stream at nearly every stage of the flight. “They attacked from the rear and from below, where they could not be seen in pitch darkness, while they could easily see us silhouetted against the lighter sky.”

Despite the dangers that were present on all bomber raids, Coulombe felt a raid on Berlin put the most strain on air-crews. “Going against Berlin, you felt overwhelmed by the immensity of the defended area. You had the feeling of the impossibility of getting through the collective opposition of so many defenses.”

The second mission for Halloran was more harrowing than the first. On the way to Berlin his aircraft was attacked by a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 night fighter. The bomber’s rear gunner signalled to the pilot to corkscrew to port, and, as the aircraft dived away, the rear gunner fired off a two-second burst from his machine guns. Bombers were notoriously out-gunned by night fighters, but on this occasion it was enough to stave off the attacker. Halloran’s crew was able to carry on, and they completed their bombing run against Berlin.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In February, the Allies launched a series of bombing raids against the airfields and aircraft production facilities in and around the city of Leipzig, Germany. Halloran’s crew was caught by an attacking Messerschmitt Me 210 night fighter, and they once again took evasive action. This time the rear gunner’s fire was more accurate: He claimed the night fighter as destroyed, but not before it had hit the aircraft with several high-calibre twenty-millimetre cannon shells. The pilot, Jack Lunn, recalled the event nearly fifty-five years later in a letter about his war experiences: “We had a few combats, the one on Leipzig put a cannon shell into the port inner engine without warning, the ground crew kept it as a souvenir. I lost 7000 ft [2,130 metres] in diving and found that I had to pull out by being as strong as an elephant. I took it steady in case anything broke.”

Cloud cover sheltered Leipzip from serious damage that night, but it failed to hide the bomber stream from the German night fighters. The loss rate of 9.5 per cent of attacking aircraft, seventy-eight in total, marked one of the worst nights of the war for Bomber Command. At least 546 crewmen did not return: They were either killed or taken prisoner, many of them wounded. Other aircraft almost certainly returned home carrying wounded or dead airmen. On average, only around twenty-five per cent of Halifax bomber crews and fifteen per cent of Lancaster crews whose aircraft were shot down managed to bail out. For the RAF and RCAF, it was a brutal result that could not be sustained, and the attack marked the beginning of the end of the period known as the Battle of Berlin. Pressure was mounting on Harris to focus bombing attacks on reducing the enemy air force and clearing the way for the invasion of Normandy — codenamed Operation Overlord — which was now less than four months away.

The last major raid by Bomber Command against Berlin occurred on the night of March 24–25, 1944. Eight hundred and eleven aircraft were sent to attack the city, but most were blown off course by severe winds. The city’s defences claimed seventy-two of the heavy bombers along with their aircrew, more than five hundred men. The 622 Squadron report indicates that Halloran’s Lancaster returned to base after the “operation was abandoned as aircraft couldn’t climb.” Crews turned back on raids for a variety of issues, often mechanical or weather-related, but no matter what the reason they would always be suspected of a lack of will to see the mission through.

The stress level for aircrew was significant, and the loss of any member of the aircrew, whether from enemy fire or from strain, could prove deadly on a mission. On one occasion Halloran’s navigator had a nervous crisis while in the air, leaving his crew blind. Halloran’s daughter, Patsy Rohoman, recalled her mother telling her, “the pilot called my dad and asked him to come up and calm him [the navigator] down, talk to him, and help him navigate.”

The final mission of the Battle of Berlin was against the city of Nuremberg, Germany, on the night of March 30–31, 1944. The bombers were caught in bright moonlight and tracked by enemy night fighters the entire way towards the target. Across the night sky, bombers were exploding left and right. Halloran’s aircraft was hit by an incendiary bomb, dropped from above, that crashed through the port wing. A total of ninety-six bombers were shot down, a loss rate of 11.8 per cent — the worst of any single bombing mission during the war. Countless more aircraft came back heavily damaged or crashed upon their return. Halloran’s aircraft somehow came through, but his squadron lost two bombers on the raid, and the squadron report grimly noted that the “broadcast winds hindered navigation and enemy fighters aided by the moon created havoc on the bomber stream.” Over the city of Nuremberg, airmen were haunted by the sight of bombers exploding all around them, illuminating the night sky, while they waited for an almost-certain attack on their own aircraft.

Advertisement

After more than twenty thousand bomber missions over Germany (counting each sortie by each plane as a single mission) the Battle of Berlin ended in defeat for the Allies in March 1944. While extensive damage was done to Berlin and to important industries, the Nazi war machine fought on. Thousands of Berliners were killed, while hundreds of thousands lost their homes. In the air, nearly 500 bombers were shot down, and more than 3,500 aircrew were killed or captured raiding the capital city, while another 550 bombers were shot down on other missions during this period. “The Berlin raids were arguably the most arduous and taxing period in the operational histories of Bomber Command and 6 Group,” wrote Bashow in his book No Prouder Place: Canadians and the Bomber Command Experience, 1939–1945. The brutal battle of attrition also had a significant impact on the effectiveness of the German Luftwaffe, but those effects would not be seen for months. Surviving a tour of duty during this period was a perilous task. Lunn, Halloran’s pilot, recalled, “only four crews out of nineteen finished the tour with me.”

Fortunately for RCAF crews, the focus of their attacks shifted to targets in France and western Germany in preparation for D-Day. These targets included German aircraft manufacturing plants, airfields, transportation networks, and therefore involved significantly shorter operations with less flying time over enemy territory.

Joe Halloran was one of the lucky ones. He completed his tour of duty, which included a bombing mission over Ouistreham, France, on D-Day. He met his sweetheart, Patricia Reynolds, who was serving in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, at a dance in Cambridge, England. They married on July 15, 1944, about ten days after his last mission. His flying logbook includes an extra entry stating that his duty of the day was bridegroom and that the one-hour mission finished with “good results.” The couple eventually settled in Toronto, where they always kept a box of Oh Henry! or Eat-More candy bars on top of the fridge — like the ones Halloran had eaten before every mission, lest they go to waste.

Like most veterans, Halloran never spoke much about the war to his children. Staring out the nose of a Lancaster, down six thousand metres to the destruction below, no doubt took its toll. His daughter recalled: “My mom told me that every once in a while my dad would get the shakes, for no reason, just shake really bad. And she used to go over and give him a hug, and she hugged him so hard that he told her he couldn’t breathe.”

Halloran, Philp, and Coulombe are just a few of the thousands of Canadian aircrew who served during the war. Together they faced a terrifying experience that is retold today at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta, and at more than two dozen other aviation museums across the country. The museum exhibits often connect Bomber Command to the history of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. In Nanton, the names of the 10,637 Canadians and citizens of other Allied nations killed while serving in the RCAF during the Second World War are etched on the Bomber Command memorial. While No. 6 RCAF Group was disbanded on September 1, 1945, following the defeat of Japan, the RCAF lives on, celebrating its one-hundredth anniversary this year.

Patsy Rohoman explained that her parents relied on each other and on their shared understanding of the war to get through the postwar period. “They had the best time at the worst time because they were at war, getting bombed all the time, and they never knew if they were going to be alive the next day,” she said. “It just puts a different perspective on your outlook. My dad especially was very appreciative of every day that he had.”

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement