Prisoner of Camp 33

On the morning of May 8, 1945, Wilhelm Rahn heard shouting from the Canadian guards, followed by gunfire and the wailing of the siren at POW Camp 33 near Petawawa, Ontario. One overjoyed guard rushed into his isolation cell, yelling, “Son, the bloody war is over. You’ll be going home soon!” From their cell windows, Rahn and his fellow detainee Hannes Schwede watched the solemn assembly in the yard of the camp as the Canadian commander read a statement announcing the German surrender. The top-ranking German — who served as camp commander among the POWs — did not immediately dismiss the prisoners. Instead, they stood and sang the German national anthem. Only this time they didn’t sing the second co-anthem that had been mandatory since 1933: the official Nazi Party song that praised Hitler and the swastika. Then Rahn’s fellow prisoners broke off and returned quietly to their barracks.

Alone in the cell where he’d been confined since a failed escape attempt, the twenty-one-year-old Rahn was subdued. All the signs had been there in the months leading up to this day, but the final truth was still shocking: Germany had lost the war. Rahn, his comrades, and his entire nation would now depend on the mercy of the victors.

Although nearly thirty-five thousand German prisoners were detained in Canada during the Second World War, Rahn was one of the few who wrote about his experiences. His memoir — penned many years later and posted online by his grandson after his death in 2013 — offers a rare first-hand account of how Canada treated its prisoners of war, and the effects of that treatment on a soldier who had grown up in Hitler’s Germany.

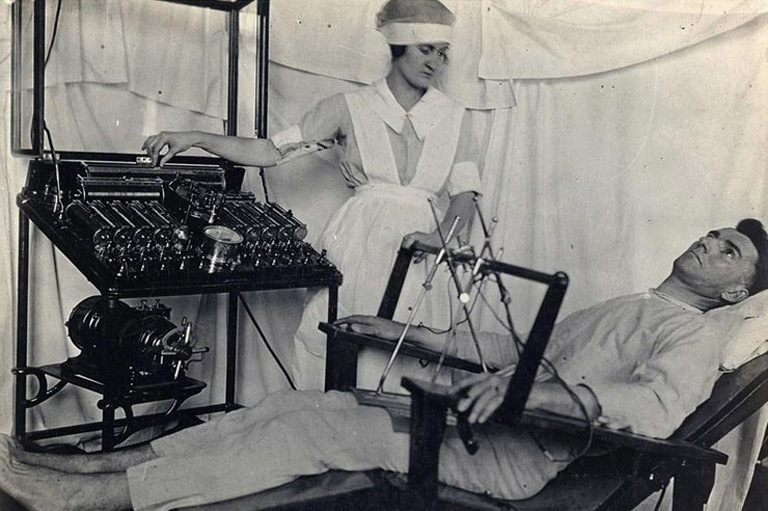

Naval Ensign Rahn was captured in January 1943 when the U-301 submarine on which he served was sunk by the British submarine HMS Sahib off the coast of Corsica. Standing watch on the bridge when three torpedoes hit, he was the sole survivor of the forty-eight-member crew, severely wounded but fished from the sea at the last minute by the helmsman of the British sub. Stoic and good humoured despite the pain, he received emergency care in the cramped British sub that had sunk his own, until his transfer to a British military hospital near Algiers. There he met doctors and nurses who, he later wrote in his memoir, “I will never forget for the rest of my life. With their medical skills and loving sympathy, they gave me the strength to go on living.”

Yet, from the moment of his capture, the young Rahn never concealed his fierce commitment to his country and its armed forces. “I was cheeky and arrogant towards the interrogators and got myself categorized with the incurable, fanatical Nazis and militarists. Indoctrinated from an early age, and a troop leader in the Hitler Youth, I was drilled and incapable of an objective assessment of National Socialism. What could you expect back then from a nineteen-year-old?”

The British intelligence report of his first interrogation was more nuanced, finding him “a pleasant type of young German, not interested in any political movement, but fully conscious of his responsibilities as a member of the German armed forces.” So, while grateful for his compassionate treatment, Rahn could not always contain his conditioned hostility. Decades later he recalled with shame one callous outburst in hospital when he rejoiced at the news of the sinking of a ship carrying British nurses: “The principal matron, who could have been my mother by age, looked at me for a long time and then said with contempt in her voice: ‘Cruel little Nazi, Willi.’”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

As a POW, Rahn’s first military duty was to try to escape and rejoin the fight. His first attempt, while still in hospital in Algeria, ended ingloriously with his fellow fugitive stuck in a sewer pipe. After being transferred to Britain, he made three more abortive tries, earning stretches of punitive detention and a reputation for slipperiness. But one February night in 1944, at the Shap Wells camp in northern England, his hopes of freedom took a major setback: “Rudely startled awake by the wailing of sirens and the excited screams of the guards, we were lined up in the main corridor of the building and informed that we had to pack our things and would leave the camp in two hours.” Loaded on a train with sealed windows, the crowd of prisoners buzzed with ominous rumours of “Kanada.” Their fears grew when they were boarded on the ocean liner IIe de France, now converted to a British troop carrier. They had known that relocation to what they jokingly called the “promised land of lumberjacks” was growing more likely; Britain could only house and feed so many POWs, and many more were sure to arrive after the anticipated invasion of France. (Although the prisoners couldn’t have known it then, the Allies would land in Normandy in just four months, on June 6, 1944). But the ocean crossing would take them even further from home and from the chance to rejoin the fight, to what they imagined as a nightmarish isolation in the frozen Canadian forests.

On board the ship, Rahn and other sailors reassured their air force and army comrades that the liner could outrun German submarines, and after a few days they approached the Canadian coast. “We could clearly see the brightly lit coast of the continent on which I was to set my feet as a POW. For all of us who had lived with the blackout for years, it was a small miracle, and someone aptly remarked, ‘They must feel pretty safe leaving the Christmas lights on.’”

Rahn was awed not only by this sense of Allied security but by his own good luck. Boarding a train in Halifax, “two pleasant surprises were in store for us: comfortable compartments, not wooden but upholstered; and a ready supper, consisting of a stew with an unusual amount of meat. We realized that we were in a country where food shortage was a foreign word.” He added, “Our guards were elderly gentlemen from the Veteran Guards of Canada [a part of the Canadian military made up of veterans of the First World War, responsible for guarding POWs and POW camps]. ... For all their friendliness, they made it clear to us that we shouldn’t get any stupid ideas about trying to get away. Outside there was only the prospect of freezing to death miserably, and, if necessary, they would burn our pelts with bullets.”

Gazing out from the train, the prisoner was carried back to the romantic visions of North America he’d dreamed of as a child in Germany. “The land seemed an endless expanse of forests, lakes, and rivers. I couldn’t help but think of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking books ... and the death of the Mohican that had shaken me so much as a child. Cooper and Karl May and [Fritz] Steuben [German authors who wrote adventure stories set in the North American wilderness] had been the favorite authors of my youth. ... We picked names from their books and tried to re-enact scenes from them.”

Crossing into Ontario, Rahn noticed English station names replacing the French ones. The train chugged up the Ottawa River valley to the military camp in Petawawa, where trucks awaited. The convoy whisked the prisoners through the camp; another hour of “more and more primitive roads into the Canadian bush” brought them to Centre Lake, with POW Camp 33 in a large clearing on its bank. The internment camp — which had previously held Italians and Italian Canadians detained as “enemy aliens” — seemed to Rahn like an island in the wild Canadian forest, with the rough road to the army camp its only connection to the outside world.

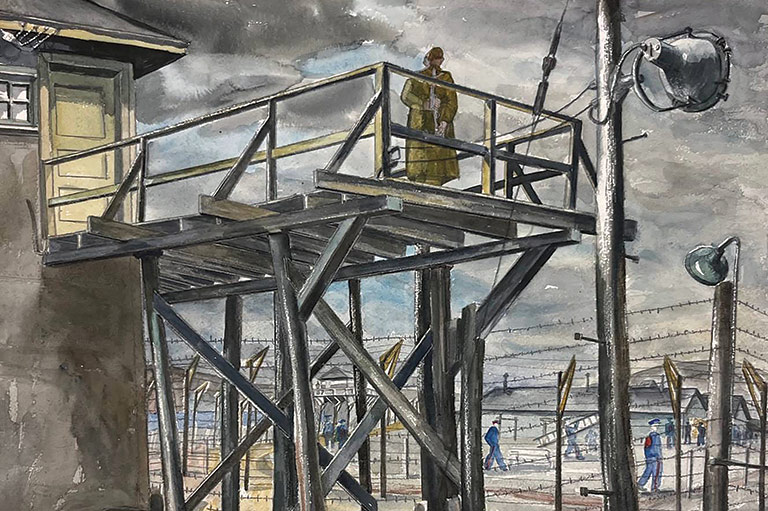

The new arrivals explored their future home: a large oval clearing, about two hundred by six hundred metres, with a cluster of wooden barracks surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence and watchtowers. As an incorrigible escape artist, Rahn immediately began scouting out weaknesses in the camp’s security, noting that the wooden huts were built on stilts to deter tunnelling and that, while the guards on the watchtowers seemed bored, they had an excellent overview from a wraparound balcony.

Each barrack was a single large room, with a row of fifteen double-storey bunks on each of its long sides. The prisoner marvelled at the “real mattresses” and the “spotless condition” of the whole camp. It had a soccer field, gym equipment, a track inside the perimeter for running or walking, and even a decent library, while “of course, our main focus was on the kitchen, because the thoughts of a POW constantly revolved around his physical well-being. We found a well-equipped kitchen and a large dining room where we had to eat all our meals in shifts.” Topping off the comforts was a canteen selling toiletries, tobacco, candy, and the like.

Advertisement

The routine of the prisoners’ everyday life was set from the first night. After a hearty dinner, they were left to card games, a “digestive walk,” and quiet sleep. Since the jailers stayed outside the perimeter, the only sounds were those of snoring and of the fire guards checking and feeding the woodstoves. Mornings began with the rush for the toilets and washroom, then breakfast. Rahn and his comrades marvelled at the abundance and quality of the food: coffee or tea, white bread (a luxury at home), butter and jam, and, on Sundays, cakes or pancakes with maple syrup. Seeing that some food was even wasted, they rejoiced in the “simple-minded belief” that this would weaken the Allies on the “food front.” They still longed for the “lost paradise” of home, but for now they could live off the fat of their opponents’ land, like “maggots in bacon.”

A morning run for the “fitness fanatics” was followed by head counts by the German camp authorities and then by the Canadians. Then, after “the ship was clean,” the prisoners were free to pursue their preferred activities until lunch. At first, most chose individual pursuits — reading, playing games, tinkering, and exercising — but they soon realized they must do more to avoid “deteriorating mentally or even becoming stupid.” Surprised at the many talents to be found in the small camp, they formed voluntary teaching groups using the skills of specialists in different fields. After lunch, they would “listen to the mattress” for a siesta before waking to a serious activity.

The Canadians delivered a mostly uncensored daily newspaper to each barrack, and those who could read English best — in his hut, it was Rahn — presented an afternoon news summary for the group. With no information on the course of the war from a German perspective, many initially distrusted the reports in the Canadian newspapers. “Propaganda” and “just crazy!” were frequent comments, especially on reported successes by the Soviet Army in the East and the Allies in the Mediterranean region. But Rahn and other sailors knew too well how the Allies’ superior technologies and tactics were overwhelming the once-dominant U-boats, and they nursed growing doubts about the leadership of the German navy and the Nazis’ boasts of invincibility.

Rahn laughed when the prisoners were offered paid work cutting wood in the bush, remembering how U-boat crews used to joke to outbound patrols: “See you again, logging in Canada!” Now these assignments were a sought-after relief from their cage, with the modest pay as a bonus. Trucked out into the woods of Algonquin Park on freezing mornings, they worked off their excess energy felling and trimming trees with double-bladed broadaxes and two-man saws. But the untrained lumberjacks often suffered injuries, and one day Rahn was caught on the head by the crown of a falling tree.

Returning from the military hospital with a turban bandage, he informed his comrades that he had met a “female being” — a nurse. None of the men had seen a woman since they’d arrived, and, as Rahn bemoaned, the extended celibate life was a real problem. They were all “healthy young fellows,” and it was only natural that their thoughts should be on women. There was hardly any sign of homosexuality in the camp, he wrote; if a couple were caught, the peer punishment would be dire, since the Nazi regime fanatically vilified, persecuted, and imprisoned gay men.

Rahn bonded with one logging-crew comrade, Hannes Schwede, who agreed that “an excursion to ultimate freedom would not be unwelcome.” At first glance, the easiest escape plan would be to abscond from the crew while working in the bush, since the guards sometimes even left their weapons unattended, assuming that the prisoners would not try to flee into the wild. But the German authorities in the camp also forbade escape attempts from the work crews. It was not worth provoking the Canadians into cutting off this healthy respite, which also gave workers the means to pay for small purchases that made life more bearable. So the two plotters would have to break out the hard way — from inside the camp, through the double fence, with the risk of being caught and, in the worst case, of catching a bullet. Camp 33 had seen eight previous escape attempts since May 1943. On average, an escapee lasted for thirty-six hours before being recaptured and brought back scared, exhausted, hungry, and tormented by insect bites.

But, as Rahn wrote later, he and his co-conspirator didn’t worry; they had “the old escaper fever ... a disease affecting the mind.” They began stealing equipment, supplies, and even a map from a forester’s truck. They dreamt up an unlikely escape route of more than one thousand kilometres: They would hike to the railway, hop on a freight train to North Bay, Ontario, then find a way south to Windsor. Crossing the U.S. border at Detroit, they would aim for Akron, Ohio, where another prisoner had relatives who might take them in. They waited impatiently for spring, stashing supplies outside the camp near the logging site and focusing on schemes to make their break.

That winter of 1944–45 seemed even longer after parcels and payments from Germany stopped in the autumn — another sign that the war was going badly for their side. Some of the prisoners succumbed to depression. Others used exercise, work in the woods, courses, and self-directed study to maintain their sanity; Rahn studied Swedish and Spanish. Ice fishing on lunch breaks helped to relieve the winter boredom, together with playing tricks on the guards. Once, some prisoners nailed a hatch shut over one guard who was checking for tunnelling. Beyond cursing the pranksters, the guards took no punitive measures. Rahn was amazed at “how good-natured the Canadians were in dealing with us young devils. It is inconceivable that something like this would have been possible in Russian or German captivity.”

Around Christmas 1944, Rahn and his comrades were briefly cheered when the authorities began to heavily censor the front pages of the newspapers delivered to the barracks — a sign of setbacks for the Allies. But their festive spirit was dashed in January by reports that Hitler’s last, desperate counter-offensive in the Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg had been rolled back in the Battle of the Bulge. Since “defeatism” was a major crime to the Nazi hardliners in the camps, most prisoners feared even discussing the possibility of Germany losing. When a couple of inmates with alleged communist sympathies did so, the guards had to segregate them to protect them from the fate of two similar defeatists who had been murdered in an Alberta camp. Yet, despite the worsening news and their secret doubts, most prisoners remained patriotic soldiers, desperately hoping that Berlin’s new V-2 rockets might turn the tide in Germany’s favour.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

By April the snow and ice began to clear, and Rahn’s escape plan came out of hibernation. He and Hannes Schwede filled their toolbox with stolen fence cutters and home-stitched civilian clothes. Once the escape committee approved, they enlisted fellow prisoners to stage a brawl as a diversion while they made a break for freedom. Rahn estimated a fifty-fifty chance of success and hoped they would not be shot like rabbits if they were spotted. On the perfect overcast evening, after the distraction drew away the guards’ attention, the two escapees cut through the fences and scrambled into the adjacent lake to wade to the safety of the forest. But as Rahn reached the trees he heard yelling from the tower behind him: “Halt, who goes there, hands up!” Shots lashed through the night, and Rahn thought: “Hannes, you poor dog.” In the dark, he could only hope that the shots were meant as a warning and not targeted to kill.

He never thought of giving up but plunged ahead, recalling tips to conserve his energy from his old Karl May cowboy books. Looking back at the camp lit up with searchlights, he felt an overwhelming sense of freedom. Only later would he learn how Schwede and his other comrades had obstructed the guards and helped to buy him time. The next day the Montreal Daily Star warned: “A fanatical young German Nazi POW, W.H. Rahn, has escaped from the Petawawa POW Camp, and is still at large.”

For forty hours he slogged toward the railway line, relying on a homemade compass and more woodland tips from the heroes of his childhood adventure novels. He even built a raft for his clothes and swam across a freezing river to skirt a road-blocked bridge. Finally reaching the railway line, however, he found that jumping a freight train was harder than it seemed in Jack London’s hobo stories. He needed to get close to a station where the trains slowed down. But there, the risk of discovery would be much higher.

He stumbled on a crew of railway workers who raised the alarm when they saw through his Canadian lumberjack impersonation — stolen clothing and knapsack, bolstered by an unlikely tale about moving from one logging company to another. He was soon tracked down by a military policeman waving his pistol. Rahn thought he was finished, but the soldier fired in the air to summon other searchers, who handcuffed the captive, put a lit cigarette in his mouth, and posed with him for photos. His army captors treated him well, restraining one captain who shouted about the “damned Germans” shooting forty-two escaped Canadian officers. When the Veterans Guard picked him up from the military police, one told him, “Don’t worry, you’re safe now.” He later hoped that his countrymen who had murdered helpless and unarmed Canadian officers got what they deserved after the war.

Back at Camp 33, he was greeted with cheers by his fellows and then paraded before the camp commandant, a “nice old gentleman” whose own son was a prisoner of the Germans. The commandant smiled and said, “Well done. But I have to punish you for stealing and damaging Canadian property.” Rahn received the mandatory twenty-eight-day sentence in segregation, where he swapped stories with Schwede, ate a good dinner, and flopped onto a bunk that “felt like a four-poster bed” after his nights in the bush.

He was still in the cells on May 8, 1945, when the news of Germany’s surrender reached the camp. The prisoners now faced the humiliation and occupation of their country and their own uncertain futures. Most of them did not expect to go home soon, and they knew home would never be the same. When Rahn was allowed out of isolation to rejoin his comrades, he found that many had already removed their rank badges and no longer felt like soldiers, although the Canadians insisted on maintaining military order. Some proclaimed their relief at the end of the Nazi plague, but Rahn was not yet ready to join them. Alert to these differences among the prisoners, their custodians were turning to the future.

Advertisement

Rahn was one of fifty men identified as troublemakers — hardline Nazis, agitators, and escapers — who were assembled and told they would be moved to another camp. At first happy to leave the monotony and isolation of Petawawa, they began to wonder about their fate during the long train journey westward to an unknown destination. Set on a barren expanse “in the middle of nowhere,” near Lethbridge, Alberta, the sprawling Camp 133 was a different world from the small enclave for eight hundred prisoners in the woods near Petawawa. Its 12,500 inhabitants were also a breed apart. Rahn immediately saw that, for them, “time seemed to have stood still.” The German camp commander greeted the new arrivals in full uniform with a Nazi salute and told them that many of the inmates — captured early in the war when the German land, sea, and air forces seemed unbeatable — still refused to accept that the war had been lost.

The prisoners had come to take for granted the Canadians’ generous treatment, part of a deliberate strategy to win them over to the merits of a democratic society. Together with excellent care and feeding, they had enjoyed full sports facilities, regular film screenings, a library that “would have done credit to any German city of a similar size,” and a wide range of academic courses, some for university credit. They had been paid to work on nearby farms, and the guards had even allowed them to keep dogs in the camp.

But now Rahn saw the Canadians take a tougher approach, determined not to send unreformed Nazis back to Germany. An RCAF officer led the re-education campaign: “First, we were shown films about the bestial conditions in the German concentration camps liberated by the Allies. The reaction to this varied. Honest dismay and thoughtfulness were reflected in many faces. But there were also wild cries of: ‘Lies, propaganda!’” Rahn was shocked that some POWs still proudly proclaimed their Nazi allegiance and treated the Canadians, who questioned them about their political views, with contempt.

Angrily, the Canadian officer “guaranteed us that he would make decent people out of us, even if we resisted. None of us would be sent home if we didn’t change our behavior. We had been coddled too much, this was the end of it and we would get a taste of what the Germans had done to others. Our rations would be cut — none of us would die, but we would feel what it was like to be hungry,” Rahn wrote. “We hooted and laughed at him. But the laughter soon died. Hunger began to churn in our guts, and it caused the solidarity of the prisoners to quickly crack. Many discarded their ranks and decorations; the Austrians discovered their national heart and donned Austrian cockades.”

The Canadians now began “separating the goats from the sheep,” dividing the POWs into new categories: the super democrats, democrats, indeterminate, militarists, and the Nazis. Democratic working groups were formed, and many friendships broke up due to conflicting views. The number of dogs in the camp suddenly decreased, as they were eaten by their masters. Only the democrats were allowed out to work for local farmers, who fed them more than camp rations. Those groups were released first, although none arrived home for many months, as they were kept for further stretches on reparation labour crews in France and Britain.

Did imprisonment change young Rahn? He never claimed any sudden conversion. In Lethbridge, he admitted, “I didn’t end up with the Nazis, but with the militarists, and I was in the right company there.” Yet the account of his years in captivity traced a gradual erosion of the total indoctrination of Hitler’s Reich, for him and for others. From the moment of his wounding and rescue, he was moved by the compassion and decency of his British and Canadian captors. Germany’s successive defeats and cruel blunders — like the failing U-boat campaign that cost so many sailors’ lives, including those of all his own shipmates — fed his doubts about the myths of German invincibility and infallible leadership so central to Nazi ideology. And the Canadians’ policy of exposing POWs to truthful information and the benefits of a free society had its intended effects on a perceptive young man. Finally, seeing the evidence from the death camps left him no room to deny the enormity of Nazi lies and crimes.

Boarding the Mauretaniain Halifax in 1946, bound for his shattered German homeland, he felt “trepidation and shame” after the humiliation of defeat and his exposure to the “unimaginable atrocities committed by Germans during the war.” Most of his companions felt the same, which may explain why few of the Germans who lived as POWs in Canada wrote or spoke publicly about their experiences. But Rahn told his young children bedtime stories about his adventures in Canada and, after retiring, wrote his extraordinary, candid memoir for his family.

Following a year of imposed labour in Britain, Rahn was returned to Germany in 1947, at the age of twenty-three. He became a policeman before joining the army of the new West German democracy, eventually reaching the rank of colonel. He was not among the six thousand former German POWs who wanted to immigrate to Canada. But he, too, held warm feelings for the country throughout his life and returned as a NATO ally in 1967 for a promotion course at the Canadian Army Command and Staff College at the historic Fort Frontenac in Kingston, Ontario. By then, the internment camps at Petawawa and Lethbridge had been razed to the ground.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from visitors like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages.

Any amount helps — your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement