Demise of an Empress

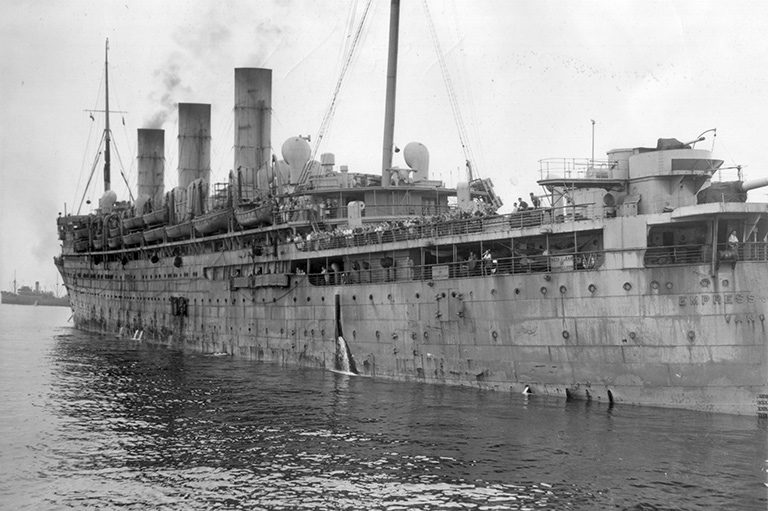

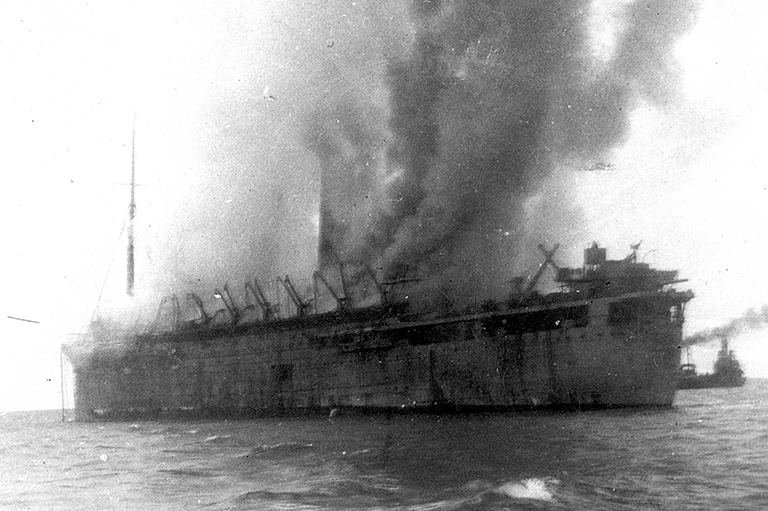

The bombs fell from their racks like steel parasites, crashing through the ship’s top deck before exploding and sending fiery debris four levels down. There was no water to fight the fire on account of damaged mains, and so the flames rose quickly, devouring the troopship from within. Windows popped; furniture and wooden decks cracked and burned. Even the steel bulkheads and heavily riveted plates groaned and buckled as frightened men with ash-covered faces ran — or jumped — for their lives aboard the 180-metre-long Empress of Asia.

Most of the crewmen and 2,235 troops on board the crippled behemoth found refuge on the bow or near the stern, away from the flames and smoke but still vulnerable to the Japanese air attack. Among the wounded were men with severe burns, fractures, and lacerations.

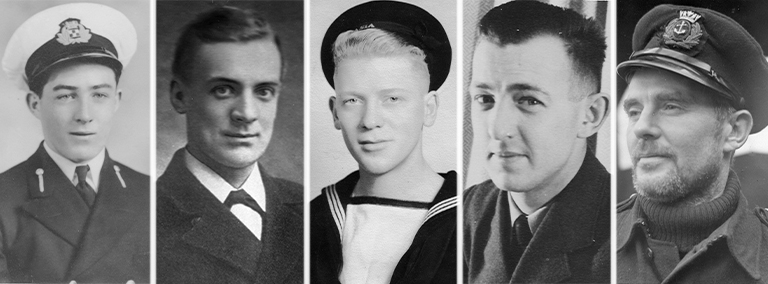

Fourth Officer Walter Oliver of New Westminster, B.C., would be among the last of the 413 crewmen to abandon the doomed Canadian-flagged troopship off Singapore. With scorched legs, he fought through dense smoke to the stern, where the small Australian warship Yarra pressed alongside in a daring rescue manoeuvre. But, before descending the ladder to the Yarra, Oliver inhaled and went below decks for one more look. The thirty-one-year-old, who had sailed the world’s oceans since 1925, never thought himself a hero, but he was someone people could trust. His was an automatic response, a split-second decision by a merchant mariner to make sure no one was left below.

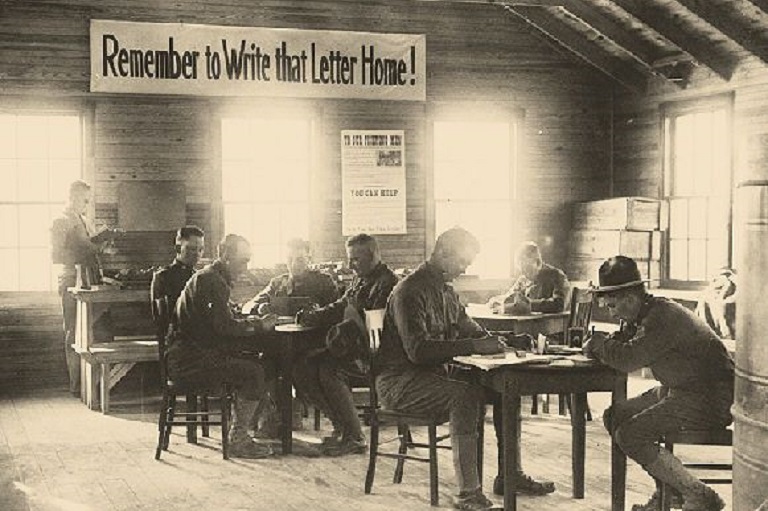

It was February 5, 1942, and the former luxury liner had been bombed twice within twenty-four hours while en route to Singapore’s Keppel Harbour. It had been plying dangerous waters for weeks, especially since embarking British reinforcements and military supplies at Bombay (now Mumbai), India, on January 23. The men, including nearly seventy Canadian crew members, had for several days sensed an imminent attack.

The Empress of Asia’s dramatic destruction off Singapore, and the plight of its crew and troops, remind us of the tremendous reach of the Second World War. The disaster also demonstrates the lesser-known role of the Canadian merchant seamen who were serving, not on the North Atlantic or in the English Channel, but in the dangerous waters of Southeast Asia. While the Empress of Asia was only one ship performing troopship duties, its story remains a stark example of service and sacrifice made far from home, beyond the main narratives of the war.

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

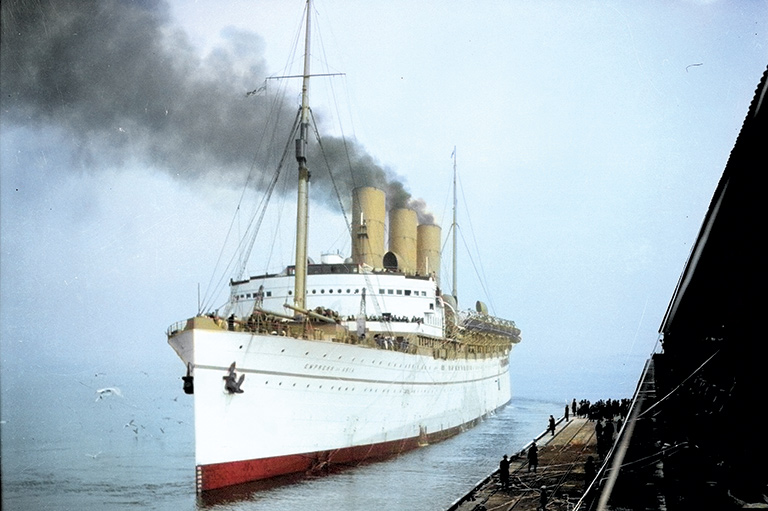

Completed in 1913 at Govan, Scotland, for the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, the Empress of Asia was known as a “three-stacker” owing to its three massive funnels. Once nicknamed “Greyhound of the Pacific” for its speedy crossings between Yokohama, Japan, and Race Rocks, B.C., by 1942 it was nearly thirty years old, scarred, and painted wartime grey. Since the start of its service in the Second World War, it had logged 90,387 kilometres. Convoy schedules and other logistical pressures meant it often travelled from port to port without fumigation or cleaning. At Halifax in 1941, graduates of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan had thumbed their noses at it, refusing to embark on the Empress of Asia for overseas due to its verminous state. Still, the old ship, which had served as an armed merchant cruiser and troop carrier in the previous world war, had a reputation for being lucky.

Below decks, in its caliginous stokehold, sweaty and calloused trimmers shovelled coal and delivered it to firemen, who fed the fuel into sixty-four furnaces. The fires fed ten cylindrical boilers that sent pressurized steam into giant turbines driving four manganese-bronze propellers for a designed service speed of eighteen knots (about thirty-three kilometres per hour). In regular service higher speeds were achieved, but this depended on good coal and a strong crew. During its interwar years, as a gleaming white passenger liner, the Empress of Asia had relied on its dedicated Chinese engine-room crew to routinely keep good steam. In July 1924, it recorded an average speed of 20.2 knots (about thirty-seven kilometres per hour) crossing the Pacific.

With so many moving parts, red-hot coals, and air saturated with coal dust, the engine room was a dangerous, unhealthy place for the 155 men who worked there. Some men likened it to being inside a blast furnace in hell, especially those who bore ugly scars or “firemen’s boils” — lesions that occur when sweat is trapped beneath the surface of the skin. In the decade leading up to the war, experienced men were hard to recruit, and those who joined up in wartime were fatalistic about surviving a boiler explosion or torpedo.

Among the smudged-faced crew who signed on for wartime duty aboard the Empress of Asia was a young “greaser,” Wesley Glover of Collingwood, Ontario, who had been sailing inland waters since 1937. As a greaser, Glover — equipped with a bucket of grease, an oil can, and some cloth — lubricated the moving parts of engines, machinery, and auxiliary equipment. The twenty-one-year-old had been among dozens of engine-room crew from the Great Lakes shipping industry who signed on in early 1941 to help deliver the liner from Vancouver to Liverpool, England, for troopship conversion. They were tough, young, experienced men, and they did a fine job of ensuring that the ship maintained an acceptable speed. But Glover was the only member of the Great Lakes complement to remain with the ship. Most of the other men returned to Ontario to assist with other wartime work. With the Great Lakes crew gone, replacements were recruited in Liverpool. Many were young men from Depression-ravaged working-class neighbourhoods; few had experience on big coal burners, and some rejected authority.

In late April 1941, while under the command of Captain John Bisset Smith, the refitted Empress of Asia commenced its Second World War troopship duties. In the course of the next eight months, it transported two thousand British troops of the Yorkshire Green Howards to North Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, the South African port city of Durban, and the Red Sea. It also travelled from the Red Sea back to Durban with Italian prisoners of war; and it crossed the Atlantic to New York, via Trinidad, with hundreds of wartime evacuees, eventually arriving at Halifax. There it joined the first Atlantic convoy escorted by American warships — HX-150 — to transport Canadian troops to Liverpool. All was not smooth sailing, however. While carrying the Yorkshire Green Howards, the ship fell dangerously behind the rest of the convoy off the coast of Africa because it could not maintain proper speed, an issue that also plagued it on the way to New York. And then, while nearing Cape Town, South Africa, on December 7, 1941, its crew learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

With the war in the Pacific and Southeast Asia expanding rapidly, ships and convoys received new sailing orders. At Durban, in late December, the Empress of Asia disembarked its North Africa-bound troops, loaded cargo and mail, and, on January 1, 1942, began a 7,050-kilometre voyage to Bombay to collect military equipment and members of the British 18th Division. On January 23, the Empress of Asia joined troopship Convoy BM-12, bound for besieged Singapore.

South of Sumatra, BM-12 rendezvoused with Convoy DM-2, and the ships steamed north into the narrow Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java. It was February 3, and by then Japanese forces, after overwhelming Allied positions on the Malay Peninsula, were poised to cross the Johore Strait onto Singapore Island, the British stronghold in Southeast Asia. The invasion of Singapore was part of Japan’s larger plan to seize imperial power over its neighbouring countries, many of which were, at the time, colonies of European empires.

Below, in the Empress of Asia’s troop decks, British soldiers dozed or tried to relax. When not on watch, the crew — including the Canadians — drifted in and out of states of quasi-readiness. Fourth Officer Oliver kept detailed handwritten notes on paper with the words “V for Victory” in the top left corner.

Working in the galley was Chef Arthur Gee, a Liverpool-born Vancouverite who went to sea at sixteen. A quiet, forty-eight-year-old man with a butterfly tattoo on his left arm, he often whistled while working. Never far from his mind were his wife, Flora; his daughters, Olga and Beverley; his son, Arthur Jr.; and his German shepherd, Fritz. Gee had recently cabled Beverley to wish her a happy ninth birthday, and on January 14, while the Empress of Asia was reaching Bombay, she had written to tell him that he was deeply missed in Vancouver. Gee had survived the loss of two ships during the previous world war; one had sunk with the cake he had asked the ship’s baker to make for his upcoming wedding.

Often manning the lower bridge was seventeen-year-old Cadet Maurice Atkins, assigned to fellow Canadian, Second Officer Cecil Crofts. Atkins had spent his early childhood in southern Alberta at a dusty crossroads called Gem, where his father had run the general store and collected hogs from area ranches in a dilapidated truck for delivery to Calgary. When the Depression worsened, the Atkinses had moved to Victoria, where Maurice had left school at fourteen in 1939 to attend His Majesty’s Ship Conway, the training school ship on the River Mersey, near Liverpool. He had joined the Empress of Asia in April 1941.

While the ship was still in Sunda Strait, Ordinary Seaman Jack Ewart stood watch in the crow’s nest, some thirty-one metres above the water. The twenty-year-old from Vancouver heard what he thought were aircraft engines. But when Ewart phoned the bridge, he was told that he was probably just hearing another ship.

Able Seaman Geoffrey Hosken was on edge, too. In a thin, bluish-green scribbler — the kind distributed to public schoolchildren — the young Vancouver man kept a diary. He had made note of the oppressive heat and humidity of the equatorial climate when he observed, on February 3, “more navy escorts” and “a plane patrol.”

When the convoy reached the northern end of Sunda Strait, several ships broke off and headed east to Batavia (now Jakarta), the capital of the Dutch colony of Java, which was also under Japanese threat. The remaining five, including the Empress of Asia, headed northwest into the winding Bangka Strait. Leading the convoy through the Bangka Strait was the repurposed British passenger and cargo ship City of Canterbury, followed by the Dutch liner Plancius, the British troopship Devonshire, the ex-French ocean liner Félix Roussèl, and, lastly, the Empress of Asia. Escorting were British cruisers HMS Exeter and HMS Danae, the Indian sloop HMIS Sutlej, the Royal Australian Navy sloop HMAS Yarra, and two destroyers.

Oliver was familiar with the Singapore approaches. Earlier in his career, the experienced merchant mariner had helped to transport oil out of the Dutch East Indies. He had even kept a cabin at Palembang in South Sumatra. Those days were gone, and, despite an array of naval escorts, Oliver knew that the troopship convoy was extremely vulnerable heading into the strait — particularly the Empress of Asia, which was last in line and carried the largest number of troops.

Hosken’s diary entry at 3:00 a.m. on February 4 demonstrates his frustration: “Lagging behind convoy as usual and cruiser keeps signalling to pick up speed for we are endangering the whole convoy. But firemen won’t or can’t get the steam. Doing 12-13 knots [twenty-two to twenty-four kilometres per hour] and about a mile behind.”

The Empress of Asia was not without firepower. Among its crew were twenty-five members drawn largely from the British Army and Royal Navy. To preserve the ship’s merchant and noncombatant status, these men — known colloquially as DEMS, for the Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships on which they served — had signed on as deckhands. However, the DEMS also had access to Bren guns, a type of light machine gun. In addition to the DEMS, several other crew members had gun training.

The ship’s anti-aircraft armament consisted of a three-inch (76-millimetre) gun fitted aft, a six-inch (152-millimetre) gun, six large-calibre Oerlikon guns, and ten Hotchkiss light machine guns, six of which were secured within machine-gun nests near the bridge. The ship also had a parachute-and-cable anti-aircraft system launched by rockets. Missing was its Bofors anti-aircraft gun, which had been transferred to the British Army in North Africa.

As dawn unfolded, a formation of twin-engine Japanese fighter bombers kept watch on the glassy sea, paying attention to the islands and channels that forced lone ships into small spaces and convoys into single file.

By 11:00 a.m. on February 4, Hosken was helping to prepare the mooring lines in anticipation of docking at Singapore, 525 kilometres to the northwest. “About 11:30 gunfire started and I looked up and saw nine planes. … Then there were eighteen. ... I started forward to get lifebelt and helmet. Was going along the starboard alleyway on A Deck, just about the Purser’s office when bang, I thought the ship was broken in half,” he wrote in his scribbler.

The Japanese aircraft dropped several bombs, but none scored a direct hit on the Empress of Asia. However, the ship was sprayed with hot, oily shrapnel that splintered lifeboats and decking. Sanitation Engineer John Drummond, also a Canadian, noted in his journal how the concussion “smashed some large, square port [windows] in the ship’s dining saloon and split iron tables in two.” He stated that the enemy was driven off by anti-aircraft fire and by two Allied fighter planes. “But this gave away our position as we were only 24-hours sail from our Destination.”

Boy Seaman Geoff Tozer, a nineteen-year-old who — like so many of his shipmates — had grown up through the Depression, saw three bombs hit astern and two more near the port side, unleashing towering columns of water. Assigned to an anti-aircraft gun, the young man from the town of Coldstream, in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, couldn’t do much about the aircraft, since they were beyond range.

Hosken wrote that “the bloody firemen came up when the first bomb was dropped” — abandoning their duty to keep the engines stoked — but they returned below when told to do so by a priest. He did not identify the priest, but it was likely a British army chaplain. If that was the case, it suggests that it was necessary in that moment to go beyond the ship’s officers to find someone of authority to deal with the problem. Hosken’s diary does not specify how many firemen came up, but he was convinced that their action caused the ship to lose speed. This view is supported by other accounts, including one by British soldier William Harris, who stated in 1989 that some ex-miners among the troops went below to stoke the ship.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In his official report, Captain Smith made no mention of this incident. He stated that the Empress of Asia was “allotted this position [last in line] on account of our steaming difficulties, the ship almost invariably dropping astern of station when fires were being cleaned.”

Interviewed in 2021, Atkins — a teenager when he served as a cadet aboard the Empress of Asia and one of the last living crew members at the time of the interview — maintained that the ship did not lose steam in the Bangka Strait but held its position. Nor did Atkins notice engine-room crew emerging on deck. However, he recalled that the ship had lost steam earlier, while off the coast of Africa. “[The firemen] were a hard bunch. … They could steam ships, but they couldn’t steam her. So we were always behind the convoy or dragging our feet.”

Later that afternoon, the convoy split in two, with the faster ships — Devonshire and Plancius, escorted by Exeter and Sutlej — pulling away from the three slower ships, escorted by Danae and Yarra. “Twilight until daylight … everything remained quiet,” noted Oliver on his “V for Victory” notepaper.

By 10:00 a.m. on February 5, the convoy’s trailing section was approaching Sultan Shoal, twenty-one kilometres southwest of Singapore’s Keppel Harbour. On the faint horizon to the north, clouds of black-grey smoke hung above Singapore, the result of Japanese aerial attacks. Speed was reduced preparatory to embarking harbour pilots, but the pilot assigned to the Empress of Asia never made it on board. Oliver noted that at 10:25 a.m. a large formation of aircraft appeared, and then it vanished into clouds. “At 10:37 action stations were again called as twenty-seven enemy planes are flying low and directly towards us.”

The three troopships and their escorts opened fire. “Bombs started falling all around the ‘EMPRESS OF ASIA’ and it was evident the ship had been singled out to bear the brunt of the attack,” wrote Captain Smith in an April 1942 report.

Atkins recalled being on the lower bridge when the attack began. “There was this guy coming down our bow with his machine-guns blazing, and I never felt so helpless in my life. He was heading straight for the ship — coming right over our bow towards us. All I could see was the machine-gun shells hitting the deck and bridge, and felt for sure one of them had my name on it.”

“As each plane attacked, and when coming out of the dive, the bombs could be seen leaving the rack,” wrote Oliver. “Next the explosion, followed by the concussion. All these aircraft attacked from forward in line with the bow at incredible speed.”

Oliver noted that, at 10:48 a.m., an incendiary bomb penetrated the upper deck between No. 1 and No. 2 funnels, exploding in the lounge and creating a fire. The blast inflicted heavy casualties among the troops sheltering below. After receiving orders to take a firefighting crew and to hook hoses to the hydrants, Atkins found that there was no water, due to damage below. With lives in the balance, the Empress of Asia’s gun crew fought back. “There were cases where the barrels of the Bren guns became so hot as to be discarded and replaced,” Oliver recorded.

At least two more bombs scored direct hits, forcing the Bren gunners to move to the upper-bridge railing, facing the bow. “The concussion of all this firing set off many of our own rockets,” noted Oliver. “Some of these flew horizontal around the bridge deck, adding … further to the confusion. The rockets with the parachutes also took off … at the wrong time, and landed with all the wiring back on deck.”

British troop Captain John Watts witnessed an incendiary oil bomb explode in the officers lounge. “We could see officers and men, blackened and burned, being passed and assisted through open windows of cabins and recreation rooms on the promenade deck.”

Twenty-three-year-old Douglas Elworthy, a member of the catering crew since January 1941, was in the pantry below the lounge when his world crashed around him. The Vancouver man’s body was sprayed with hot, oily shrapnel.

The evacuation of the engine room was ordered, and at 12:15 p.m. those on the bridge were told to leave. Among them was Crofts, the Canadian second officer who supervised the young cadet Atkins. Crofts fractured a leg jumping nine metres to the foredeck. By then the ship’s lifeboats were burning. Two were launched, but one of them capsized. Tozer, the boy seaman, was staring at the water off the port side when he spotted the severely wounded caterer, Elworthy, clinging to a swamped lifeboat.

On the bow, Atkins and Ordinary Seaman William McKinnon of Vancouver lowered loops of mooring line over the port side, which allowed dozens of men in life jackets to slide fourteen metres into the sea. “[McKinnon and I] went over the side together,” Atkins later recalled. “The fire was on the bridge — that’s where it was really burning. We went into the water … swam around until a boat picked us up.”

While the Australian navy sloop Yarra stuck herself to the port quarter of the Empress of Asia to rescue men from the burning ship, Canadian Ordinary Seaman Ernie Higgs noticed hundreds of spent anti-aircraft brass cartridges stacked like cordwood on the Yarra’s deck — remnants from its attempt to bring down enemy aircraft. When Oliver went below decks on the Empress of Asia to check for remaining crew — before seeking safety for himself aboard the Yarra — he located a man from the engine room sitting stoically in the dark, “his face flushed and sweating profusely.” When he asked the fellow why he hadn’t abandoned ship, the response was that he had not received the order. Oliver quickly convinced the dedicated seaman to follow him up and out of the engine room.

Burning fiercely amidships, the wounded Empress of Asia drifted southeast of Sultan Shoal and dropped anchor. Hosken noted that 1,600 men were rescued by the Yarra, although other estimates say 1,800.

Of the 2,648 men on the Empress of Asia, only sixteen soldiers and four crew members died, while 238 were wounded. The toll would have been higher if the Yarra hadn’t put itself in harm’s way, or if the troopship’s crewmen hadn’t fought back and helped others to escape. It is clear that the Empress of Asia experienced frequent and serious steaming difficulties, but not all of the blame should be assigned to all of the members of the stokehold. Well-run ships depend on solid leadership, structure and discipline, and an adequately large crew. But, in the stark reality of war, the Empress of Asia fell short when all of those qualities were needed most.

The smouldering wreck, along with its cargo, eventually sank in shallow water. But the drama was not over. While most of the British soldiers were dispatched to various duties, the injured crew — including Crofts, with his fractured leg, and the severely burned Elworthy — were hospitalized in Singapore. Healthier men, including Atkins, arrived in damp, dirty clothes at the city’s exclusive Tanglin Club or the Seamen’s Mission, where — while bunking down in the cellar — Oliver observed two of the largest rats he had ever seen. On February 7, the majority of the crew was transported to No. 7 Reinforcement Camp in north-central Singapore, and that evening the Empress of Asia’s firemen, including Glover — the greaser who had started his maritime career plying the Great Lakes — were shipped out on the Félix Roussèl and the City of Canterbury.

On February 9, the morning after the Japanese crossed Johore Strait, the ship’s medical department and catering crew, including Chef Gee, volunteered for the Civil Medical Services in Singapore. Nearly 130 of them served at the General Hospital, and seven more served at the Miyako Hospital. Meanwhile, the Japanese invasion intensified, claiming military and civilian lives. Above the reinforcement camp, artillery shells pierced the air. Oliver recalled one striking the camp early on February 10. “The situation is grim and deteriorating hourly and only time will tell,” he noted. Hosken’s diary states: “Got news about men on ship. 15 killed and 4 missing, 235 casualties. Doug Elworthy dyed [sic] in hospital today of severe burns.”

At 4:00 p.m, orders were given to collect the encamped Empress of Asia crew and to transport them to the harbour. There, nearly 120 men — from carpenters, to engineers, to officers — were given instructions to commandeer three Malayan coastal vessels, the Sin Kheng Seng, the Ampang, and the Hong Kwong, to escape the imminent Japanese conquest of the island. Each ship was approximately thirty-five metres long.

On February 11, 1942, Oliver and Drummond boarded the Hong Kwong, accompanied by thirtysix other Empress of Asia men, a lieutenant of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, and eight army stragglers.

The diarist Hosken, Captain Smith, and thirtyeight other men, including Canadians Atkins, Ewart, and Higgs, boarded the Sin Kheng Seng. Among the Canadians on board the Ampang were Tozer, First Officer Leonard Johnston, Cadet Arthur Le Patourel, Engineer Herbert Stainton, Chief Officer Donald Smith, and McKinnon, the ordinary seaman who, along with Atkins, had lowered the Empress of Asia’s mooring lines to the water, allowing many men to escape with their lives.

At 3:00 p.m., the vessels proceeded at a full speed of six knots (about eleven kilometres per hour) through the breakwaters and out of the harbour, skirting minefields on a southeastward course with other escaping vessels. “The ships are under constant aerial attack. … We had one near miss, a very close near miss; it felt like the ship was falling apart, the concussion being so violent,” noted Oliver. The Hong Kwong and Sin Kheng Seng reached Batavia.

The Ampang was not as lucky. It ran short of fuel and was abandoned on a river in Sumatra, as hundreds of enemy paratroopers landed with the intention of seizing the island’s oil refineries. The passengers, including Canadianborn Betsy Spicer — the wife of a British naval officer — disembarked and found cover along the river. Spicer handed out some canned food that she had brought along, and — with the help of local inhabitants and British military personnel — the escapees commandeered a bus, drove as far as possible, then hiked for many kilometres until they boarded a train for Baturaja, South Sumatra. On the south coast, the group boarded another vessel, crossed the Sunda Strait, and eventually reached Batavia.

Sixty-seven days after escaping from Singapore, the first group of survivors reached Halifax. One Vancouver-bound crewman, the barrel-chested Quartermaster Ernest Punter, boarded the train wearing a second-hand suit, compliments of the Halifax Red Cross. The ship’s chef and catering crew were interned at the Changi and Sime Road prison camps in Singapore until war’s end. Suffering the same fate was Second Officer Crofts, whose mother died the day the first group of survivors reached Halifax.

Unknown to Chef Arthur Gee, his only son, nineteen-year-old Arthur Gee Jr., was among the lost crew of the SS Northholm, a cargo ship that sank in rough weather off Vancouver Island on January 16, 1943. Understandably, the family kept the horrible news quiet until after Gee was liberated. Meanwhile, everything was done to keep Gee’s beloved dog, Fritz, healthy. When the chef finally arrived home, the old shepherd was under the kitchen table. Sensing his master’s presence, Fritz didn’t get up, but Gee’s wife, Beverley, distinctly remembers the wag of his tail.

The Last Voyage of the Empress Of Asia

- South of Sumatra, Convoy BM-12, which included the Empress of Asia, rendezvoused with Convoy DM-2.

- On February 3, 1942, the ships steamed north into the narrow Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java.

- Meanwhile, Japanese ground forces on the Malay Peninsula were poised to cross the Johore Strait onto Singapore Island.

- When the convoy reached the northern end of Sunda Strait, several ships broke off and headed east to Batavia (now Jakarta), the capital of the Dutch colony of Java.

- The remaining five ships, including the Empress of Asia, headed with their escorts into the winding Bangka Strait off the east coast of Sumatra.

- On the morning of February 4, Japanese fighter bombers attacked the convoy, but none of them scored a direct hit. The Japanese were driven off by anti-aircraft fire and two Allied fighter planes.

- In the afternoon of February 4, the convoy split in two, with the faster ships, Devonshire and Plancius, escorted by Exeter and Sutlej, pulling away from the three slower ships, escorted by Danae and Yarra.

- On the morning of February 5, the convoy’s trailing section, including the Empress of Asia, was approaching Sultan Shoal, twenty-one kilometres southwest of Singapore’s Keppel Harbour, when Japanese planes attacked and destroyed the Empress of Asia.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement