D-Day Memories

“Suddenly the ramp went down and the men jumped into water up to their armpits. I was the seventh man out. Bullets whizzed around us and smacked into the boat and into the men. Being the centre craft, we were in the zone of concentrated crossfire.

Men were being hit and disappearing into the water. [When] the chap in front of me … jumped, he went under at once…. I leaned over to haul him to the surface. At that moment, I felt as though someone had struck me with all their power with a baseball bat and I was knocked flat into the water. My left arm would not work.”

So remembered Lieutenant John D. McLean, who landed with “B” Company of the Queen’s Own Rifles at Bernièressur-Mer on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

The invasion of Normandy, France, was one of the key moments in the Second World War. A successful landing would mark the beginning of the end for Hitler’s Third Reich.

The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was one of the assault formations at the forefront of the invasion. By the end of the day the Canadians had secured a bridgehead in France and had advanced farther than any other troops.

Of the twenty-one thousand troops that landed on Juno Beach, two-thirds were Canadian. Nearly six hundred more men landed east of the Orne River with 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. Canada also contributed thirty-seven Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) squadrons along with 110 ships and ten thousand sailors to Operation Overlord. The invasion was a success, but the cost was high. By the end of the day, 359 Canadians were dead and 715 more wounded.

Every Canadian soldier, sailor, and airman on June 6, 1944, was a volunteer. They left behind their families and careers to go to war for an important cause. Here, in their own words, are some of the men who took part in this momentous battle.

MENACING MINEFIELDS

Able Seaman Frank Turnbull enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve in 1942 and was assigned to work with landing craft. He participated in the invasions of Sicily, southern France, and Greece. On June 6, 1944, he was aboard Landing Craft Assault (LCA) 1151, the Daisy Mae, part of the 529 LCA Flotilla attached to HMCS Prince David. His craft was the only one in his flotilla that made the twelve-kilometre voyage to the shore unscathed.

At last the town of Bernières-sur-Mer, our objective, loomed on the horizon, and all that was to be seen were fires, and out of the fires the odd church steeple. About one mile from the beach, the signal was given for a deploy, and the flotillas moved in abreast. We had been told of the minefields guarding the beaches, and as we moved in at half speed ahead the mines could be seen spread out for a distance of about five hundred yards, all very close, making it seemingly impossible for an LCA to get through.

As I looked over the bow and saw the dead bodies of marine commandos floating in the water, I realized what we were facing. The marines were supposed to have cleared the way for us, and their being dead meant that we had to make our own way through these perilous stakes in the water. I was ready at any minute to be blown sky-high.

To make matters worse, mortars were screaming over the craft, and the odd Nazi sniper onshore was trying to find a good target. As we managed to skim through three rows of mines and were ready to sneak through the fourth, the craft on our starboard side broke literally in two as she hit a mine. Then, as I glanced around, I could see the craft in our flotilla, only a matter of feet away, being blown in two, holes in their bows, holes in their sterns, and sinking rapidly, but not before the soldiers were on their way ashore in waist-deep water.

With all the craft in Turnbull’s flotilla damaged, the men were to be taken off the beach in the Daisy Mae. But by then the LCA was sunk. Turnbull and his men transferred to a nearby Landing Craft Tank (LCT), which hit a mine, so another LCT took them to safety. “Never before had I seen so much strain in men’s faces…. However, after a cigarette and a shot of rum, our nerves were calmed one hundred percent and we were once more civilized.”

SHATTERING SALVOS

Lieutenant Commander Desmond “Debbie” Piers was an experienced naval commander who had learned his trade escorting convoys from North America to the United Kingdom along the famous North Atlantic run. He was rewarded with a Distinguished Service Cross for his efforts. On June 6, 1944, he was the commanding officer of the Canadian destroyer HMCS Algonquin.

As our group steamed slowly ... towards the gate, this was the opportunity to brief the ship’s company. All the sailors knew we had come south to take part in the invasion, but the important details had not been divulged.

“Clear Lower Deck” was piped, all hands mustered around the torpedo tubes. It was my turn. Even before I commenced, I could sense the high spirits of the men; confidence beamed from their smiling faces. Their good humour could not be subdued by the serious possibilities I present to them of being mined, dive bombed, shelled, and other hazards. I felt more like Bob Hope at a navy concert without a script. When I finished, the sailors all clapped…. It was still dark, about 0400 on D-Day, when things began to happen. Our force was about 35 miles from the coast of Normandy. Flares, rockets and gunfire began to light up the sky from inshore....

First thing we knew there was the coast of Normandy right in front of us, about 10 miles away. To our surprise, all was now quiet ashore. Shortly after this, the cruisers opened up on the big shore batteries.... With guns trained, loaded, and ready to fire on our prearranged target of the two 75-mm guns west of St. Aubinsur-Mer, the destroyers moved in as the spearhead of the assault to a distance of three miles.... Then we let loose. Our own target was between some houses right on the beach. First, we plastered the area with salvo after salvo of accurate broadsides. When there was no further reply from the 75-mm guns, we set about demolishing any houses along the waterfront which looked likely places for sniper nests…. At H Hour, 0745, we ceased fire, and the first flight of landing craft touched down on schedule….

The Algonquin spent the rest of D-Day providing naval gunfire support to the troops ashore and continued to support the invasion until June 26.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

TAKING THE HIGH GROUND

Major Lockhart “Lockie” R. Fulton was a trooper in the 12th Manitoba Dragoons who was commissioned from the ranks. On D-Day Fulton was among the first officers ashore on Juno Beach, as he landed with his “D” Company on Mike Red Beach in front of the present-day site of the Juno Beach Centre in Courseulles-sur-Mer, France.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles were designated an assault battalion for the D-Day landings, and Companies “B” and “D” were chosen to lead the assault …. We boarded the LSI [Landing Ship Infantry], the Canterbury, on June 3, but it was not until the evening of June 5 that we weighed anchor, moved out into the Channel, and headed for Normandy.

Only the ship’s captain, the landing craft commander, and I knew the exact destination. Once past the point of no return, I issued true maps to all detachment commanders, who, for security reasons, had been briefed on false ones. I went over the battle plans with “D” Company’s platoon commanders, then tried to get some sleep. Tension was mounting, however, and I went up on the bridge and spent the remainder of the night with the ship’s captain.

The LCAs took us as far as they could, but we still went into waist-deep water. The Germans were now alert ... and mortars began shelling the beach. It is hard to describe the difficulty of getting through sea water and across the beach to the relative safety of the sand dunes, with your battledress full of water and carrying a heavy load of ammunition and equipment….

On top of the sand dunes the Germans had laid minefields, stretching right across the company’s front. Lacking time and equipment to lift them, we would have to make our way through them and trust to luck …. Lieutenant Jack Mitchell, who won the Military Cross, led his platoon through the minefields and with tank support was able to overcome the weapon pits and capture the Germans manning them. Our other two platoons moved through the minefields meeting little resistance and attained our objective, the high ground behind Graye-sur-Mer overlooking the beach…. June 6, 1944, is a day that will remain forever in the memories of those who survived.

Fulton was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his actions on June 6, 1944, and in the days that followed. In late 1944 Fulton took command of the regiment and was considered an intelligent and respected commanding officer.

FIERCE GERMAN COUNTER-ATTACKS

On D-Day, Garth Webb was a twenty-six-year-old artillery lieutenant serving as a gun position officer for “C” Troop, 66th Battery, 14th Field Regiment.

We proceeded up the road to a gun position ... and pulled into this field. We did not know, but we were right in the vision of a [German] 88-mm gun. From the rear on the right were two Able Troop guns and then our two Charlie Troop guns. We were lying in the field when the 88 started firing.

They blew up the first Able Troop gun, which was the most distant from us. And it was a dreadful explosion. The 105 mm SP [Self-Propelled] guns were on a Sherman tank chassis with the turret removed, and the encased part was loaded with ammunition plus a big supply of infantry ammo that we were bringing ashore. Needless to say, when the gun got hit, the explosion was tremendous.

They then hit the second “A” Troop gun. Next they hit one of my “C” Troop guns.… The fourth gun, also one of our “C” Troop guns, we were able to manoeuvre out of the field and back onto the laneway, which was protected by a hedge and no longer visible…

After the enemy shot up our guns we went back and regrouped in a church courtyard with our remaining two guns.

Nine members of 14th Field Regiment were killed in this ambush. In 2006 surviving veterans, including Webb, unveiled a monument at Bernières-sur-Mer to mark this action.

CAPTURING THE BEACH

Corporal Wilfred Bennett enlisted in the RCAF in September 1939. He wanted to be a pilot, but after waiting to be called up he ran out of patience and approached the Royal Winnipeg Rifles (RWR) who accepted him without hesitation. He heard from the air force three days later, but by then he was fated to land on Juno Beach with the RWR.

The beach was pretty nasty [when] we came in about 7:30 a.m. The water was very, very rough, and on our LCA coming in we’d sit on the top of a high wave crest and then plunge straight down into a huge hole in the trough. Quite an experience for a boy from the midwest.

When we landed and hit the beach, another chap and I were running along the beach side by side. The Germans were in pillboxes and they had loaded their machine guns with tracer bullets.… It looked like yellow popcorn, popcorn floating upwards, and those were just the ones we could see. There were hundreds of bullets we didn’t see.

The man beside me got hit in the face. He was on my right side, and the fire was coming in from ten o’clock on the left, so [it] missed me and hit Kelly McTier from the MO’s office in the Rifles. I remember saying, “Well, Kelly, you’ll be back to Blighty” and then had to leave him as we were to “keep moving….”

On thinking back, the Luftwaffe did come in and start strafing some of the ships on a couple of occasions at night, and that’s why the ships were flying barrage balloons. Then it became just a rule for us: Just don’t fly near a ship. You knew you’d get shot at by them as much as anybody else…. There were some four thousand ships, and when all of them start firing together you got a fireworks display.”

Years later, Bennett saw McTier at a reunion. He told him, “Benny, do you know how long I spent on the beach on D-Day? Till six at night. It was pretty rough.”

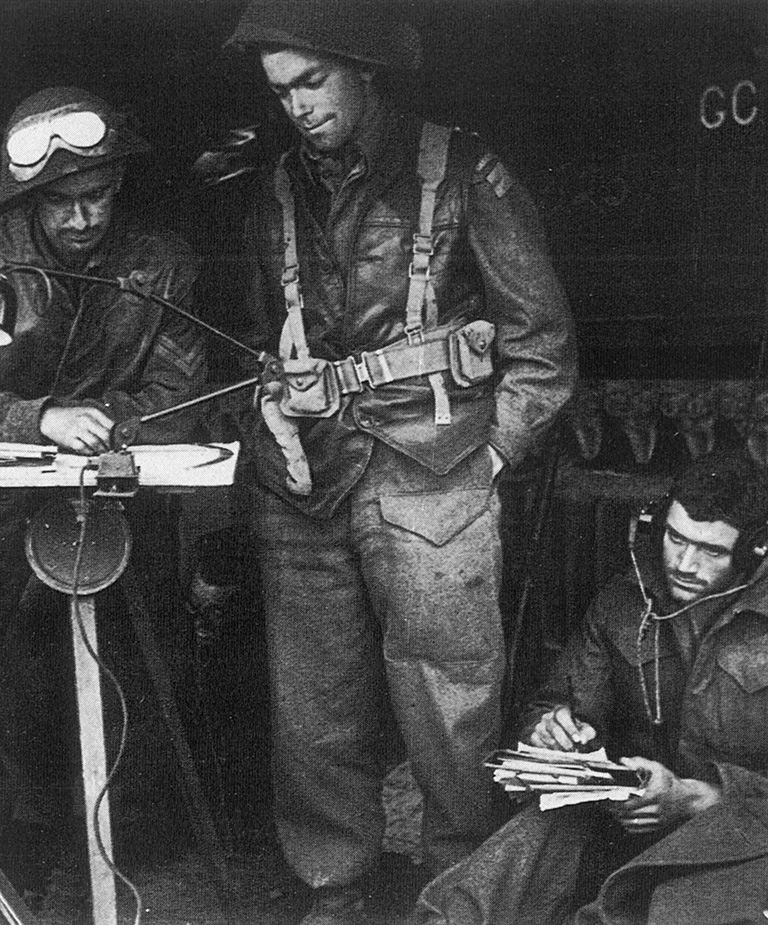

PROTECTING THE GROUND TROOPS

Squadron Leader J. Danforth “Danny” Browne was born in New Jersey, but his mother hailed from Nova Scotia, so he took a train to Montreal in 1940 and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force. In the spring of 1944 he was given command of 441 Squadron.

[My squadron’s] objective on D-Day, while the beachhead was being established and consolidated, was to provide fighter cover over the beaches in the eastern assault: Sword, Gold, and Juno…. I led my 441 Squadron in four times that day. I was Deputy Wing Leader; that meant secondin- command to [Johnnie] Johnson [the famous British ace], and it was up to me to take over the wing if he was absent. I took out our first June 6 patrol at 0625. If your preparations hadn’t been adequate at that point there was nothing you could do about it. You were either ready or you weren’t. We were ready. There was an incredible armada along those beaches.

On thinking back, the Luftwaffe did come in and start strafing some of the ships on a couple of occasions at night, and that’s why the ships were flying barrage balloons. Then it became just a rule for us: Just don’t fly near a ship. You knew you’d get shot at by them as much as anybody else…. There were some four thousand ships, and when all of them start firing together you got a fireworks display.”

Browne was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and returned to Canada in October 1944. The following month he returned to Europe, where he commanded 421 Squadron until the end of the war.

The D-Day invasion was more successful than anyone could have dared to hope. And, while many hard months of fighting lay ahead, it was the beginning of the end for Hitler’s Nazi Germany. After the war, most Canadians returned home and left the war behind. Many never talked about their experiences and were rarely asked.

“Looking back … it was so awful,” said Wilfred Bennett. “I was there, and got through, but I cannot explain why or how …. That part of my life has not been forgotten.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.