Breakdown

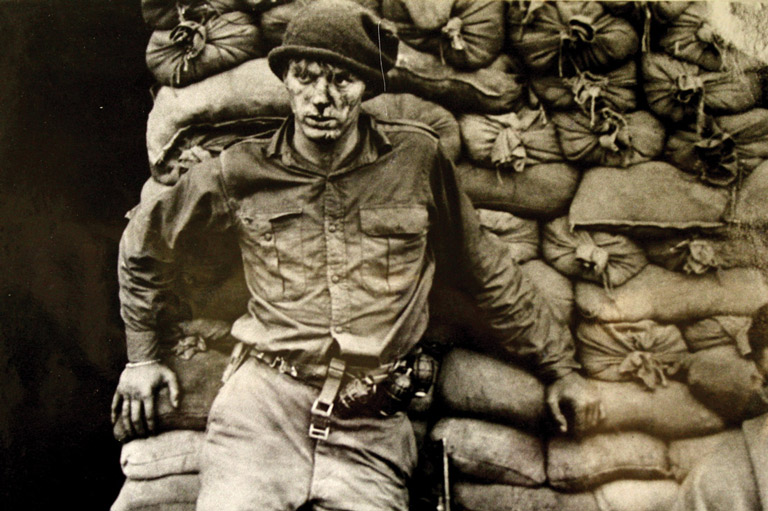

Lance Corporal Len Badowich returned from a Korean War prison camp expecting a hero's welcome. He had no idea that his release from captivity would prove almost as harsh as the time he had spent being brutally interrogated by Chinese Communist soldiers.

Badowich could accept that the enemy called him a liar; what he couldn't understand was why his own people treated him like a criminal.

The young rifleman's ordeal began on the night of May 2-3, 1953. Badowich and his Royal Canadian Regiment platoon were defending Hill 187 along the 38th Parallel dividing North and South Korea. Chinese forces swarmed a forward trench, taking Badowich and six of his platoon mates prisoner. They marched northward to an abandoned farm, where the interrogations began.

At first, the process seemed relatively harmless. Then, the Chinese learned that the soldier from Brandon, Manitoba, had trained South Korean volunteers in the UN armies. The questioning suddenly grew intense.

”When is the South Korean army going to take over from the Canadian Army?” the interrogator barked at him in perfect English.

Badowich thought, ”How the hell would I know? I'm nineteen years old, a nobody and they're asking me political and strategic questions.”

”What rank do you hold?” the man continued.

”Lance corporal,” Badowich said, but the Chinese were unfamiliar with Canadian ranks, so it merely infuriated the interrogator.

”No. You're higher than that. You train Koreans!”

The cross-examination went on for three days, with the interrogator pushing Badowich for information and Badowich unwilling and indeed unable to provide it. For his trouble, he faced reduced rations, beatings, sensory deprivation in solitary confinement, and monotonous brainwashing sessions.

They even blamed Badowich and his comrades for a cholera epidemic spreading across North Korea and China. They wanted the Canadians to sign petitions criticizing the United Nations and the Red Cross for triggering the Korean War.

“They blamed the epidemic on [us and the UN] dropping germ bombs,” Badowich said. “But we didn't sign any of the petitions.”

If his treatment at the hands of the Communist Chinese seemed abusive, Badowich soon discovered that his homecoming would be equally so.

”When I got back,” after the truce in July 1953, Badowich recalled, “the first thing they did was have us swear allegiance to the Queen [Elizabeth II] because the King [George VI] had died.”

Despite having resisted brainwashing and pressure to sign petitions, the loyalty of the freed POWs was clearly in question. It was the time of the Communist “red scare.” There was suspicion that captive soldiers had been brainwashed into working for the Communist cause. Canadian non-commissioned officers mingled among the former prisoners, listening for any signs of Communist sympathy.

”Then, there was more interrogation by our own intelligence,” Badowich continued, “as if we'd committed a crime. ‘Why didn't you escape?’ they asked us. How the hell do you escape in Korea where everybody is Oriental and you're white? Where do you go? Nobody could have escaped. These assholes made us feel like we had committed a crime — or deserted.”

The only comfort Badowich received upon his return was a steak-and-ice-cream dinner on his first night of freedom. There was no debriefing, just a delousing. There was no decompressing, just a clean uniform, boots, and reassignment to his unit. He was given a basic physical, but no effort was made to assess the state of his mind after months of confinement and attempted brainwashing. His Canadian military masters seemed to have little interest in dealing with what has at various times been known as shell shock, combat fatigue, or battle exhaustion — a syndrome now know by the label post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The military did provide former POWs with an assessment of sorts. Canadian Intelligence officers issued grades to all thirty-three Canadians who had been taken captive in North Korea. The colour-coded grades ranked them for their performance during internment in North Korea. A white grade meant undistinguished performance with satisfactory resistance. A light grey grade meant low resistance. And a black grade indicated low resistance and suspicion of collaboration with the enemy.

Eleven Canadians were graded light grey, nineteen POWs were graded white, one got black, and the last two were not graded. In other words, Canadian officials graded the majority of Canadian POWs' performance in Korea between satisfactory and undistinguished. None was considered better than average in the service of his country while in military prison.

There is no definitive evidence of Canadians in North Korean prison camps collaborating with their captors. Indeed, there is every reason to believe that the thirty-three Canadians who were imprisoned there resisted interrogation and indoctrination and that they even sabotaged Chinese brainwashing attempts to a man.

The psychological trauma suffered by Korean War vets took many forms. Some could not cope with their emotions. Some, like Ted Zuber, lost their ability to feel anything at all. Zuber, an artist, joined Canada's Special Force for Korea during the first summer of the war, volunteering for sniper training. By October 1952, he was on the frontlines with the Royal Canadian Regiment at a place called the Hook.

One night, Zuber crawled into a tunnel to catch up on some sleep. Beside him underground were a combat engineer, two South Korean labourers, a signaller friend, and about twenty new recruits. The reinforcements were preparing their weapons for the night's deployment. One of the men was told to prime a box of a dozen grenades in the tunnel. At about midnight, one of the grenades slipped from the recruit's hands. The resulting explosion decapitated one of the Korean workers and left the other Korean with severe chest wounds. The blast also broke the engineer's leg in two places, blew the signaller's foot off, and peppered shrapnel into the back of Zuber's legs and buttocks.

When Zuber and the severely wounded South Korean arrived at a regimental aid station, Zuber directed a medic to attend to the South Korean first because his wounds were clearly life-threatening. But a medical officer noticed and shouted, “Hey! Our own first!”

”Something struck me,” Zuber said. “I would appreciate that decision if I was really hurt. But I also remember being emotionally torn. So how should I feel after what [the officer] had just done to this corporal medic? And to the South Korean?”

Zuber described the South Korean's last moments, the creaking sound of the man's unconscious struggle to breathe, and his eventual stillness in death. He wanted to feel sympathy and loss, but he couldn't feel a thing.

”Emotion was a luxury we had learned to give up,” he said. “You never thought of dying because you learned how to live without that thought. Emotion was something you just didn't tolerate.”

Ted Zuber didn't fully realize this until after he'd returned to Canada. It happened when he pulled out some of the sketches he'd made in Korea. Most were field renderings of buddies resting, showering, hanging their laundry, and writing letters home. He realized there was something missing.

”Their faces were like clay,” he said. “There was nothing there.... They were emotionless. In an exaggerated way they were about as interesting as a topographical map.... The drawings were totally useless to me. I never used any of them in my paintings. I wasn't allowing myself to [feel] anything while I was there. So the one thing I injected [into paintings] later was the emotion.”

Like Badowich, Ted Zuber never received a full psychological debriefing. No official assessment was given.

This would not be the case today Canadian soldiers who have returned from tours of duty in Afghanistan or from the peacekeeping missions of the 1980s and 1990s have been debriefed and decompressed before returning to civilian life. At the time of Korean War, though, returning veterans were considered, in the words of one platoon commander, to be little more than “an administrative problem to the processing staff.”

One of those “administrative problems” was George Griffiths, who suffered far-reaching effects from his experience in Korea.

Like Len Badowich, Griffiths spent much of the last year of the war in a Chinese POW camp in North Korea. On August 23, 1953, when he was released to the UN side of the 38th Parallel, he was deloused, given a new set of clothes, and fed a big meal with Coca-Cola and beer. The food was so rich that he got sick. He flew home aboard a Canadian Pacific passenger plane.

Aside from the bits of shrapnel he still carried in his body, he had only two mementoes of his imprisonment. One was a crucifix he'd fashioned from an empty tube of toothpaste. The other was a tiny booklet made from cigarette papers that contained all the names and addresses of the POWs with whom he'd been imprisoned. He'd hidden it under his belt during his imprisonment. After his release, the Canadian government confiscated it.

Some years later, Griffiths landed government work as a prison guard. In 1982, he was on duty at Ontario's Warkworth Penitentiary when there was an attempted escape.

Suddenly, he was back in North Korea in 1952 and a prisoner again, remembering the ten months of deprivation and brainwashing, reliving his own attempt to escape.

”I had one prisoner ahead of me and another behind,” he recalled. “And I fired three times at the prisoner going by me. I wanted him dead.... I wanted him killed the same way [the Chinese] killed a Canadian soldier and walked over him in Korea.... You see, in my mind, I was surrounded again.... I was still a prisoner.”

The shots George Griffiths fired missed the prisoners. His bosses removed him from the job, but they couldn't remove the cause of his anger. Like so many other Korean War vets, he would have to cope with shell shock on his own.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!