Hope Floats

Nothing says family fun like exploring one of Nova Scotia’s worst boondoggles — a transportation megaproject that nearly bankrupted investors on both sides of the Atlantic and that, almost immediately after it was completed, was made obsolete.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Our story begins during my last trip home to Nova Scotia. I usually spend most of my time in Pugwash, on the province’s north shore, visiting my parents. But I always make time to stop by Dartmouth, located across the harbour from Halifax, to visit my sister and her family.

The last time we got together, my sister suggested that we all go for a hike southwest of Halifax to view the remnants of some Second World War coastal defences. This time we decided to stay closer to home — a ten-minute drive away, to be exact — to explore Shubie Park, home to a historic canal that in the 1800s was touted as an economic El Dorado for what was then a British colony.

Dartmouth’s nickname is the City of Lakes, and Shubie Park, nestled between Lake Micmac and Lake Charles, is a sixteen-hectare oasis of placid waters and lush deciduous forest in the middle of the city. It lies within the Acadian forest zone and boasts several varieties of maples and birches, along with a hemlock estimated to be 178 years old.

We pull into the parking lot at the Fairbanks Centre, the park’s interpretation centre. As a history buff, my first instinct is to head inside to check out the miniature model of the Shubenacadie Canal, as well as to read the biographies of the key players behind its construction. But the centre would have to wait — my son and his two cousins were already bounding down a trail towards Lock 3 — one of nineteen planned locks (only nine were completed) along the canal route that stretches 114 kilometres through central Nova Scotia from Halifax Harbour to the Bay of Fundy.

Time for some history — but I warn you, it’s convoluted, somewhat depressing, and would require many more words to fully do justice to the story’s many twists and turns.

It begins with the Mi’kmaq — the province’s original inhabitants — who in the 1600s introduced newcomers from France, called Acadians, to the lakes and waterways of central Nova Scotia, including the tidal Shubenacadie River.

After the British, who were based in Halifax, expelled the Acadians in 1755, their thoughts turned to commerce and profit. Eager to cut down shipping time, some merchants mused about digging a canal from Halifax to the Bay of Fundy as a way of quickly reaching markets in what’s now New Brunswick and on the eastern seaboard of the United States.

In 1796, they conducted a feasibility study for a Shubenacadie Canal, but it went nowhere. In 1824, a second study was conducted by Francis Hall, a Scottish civil engineer.

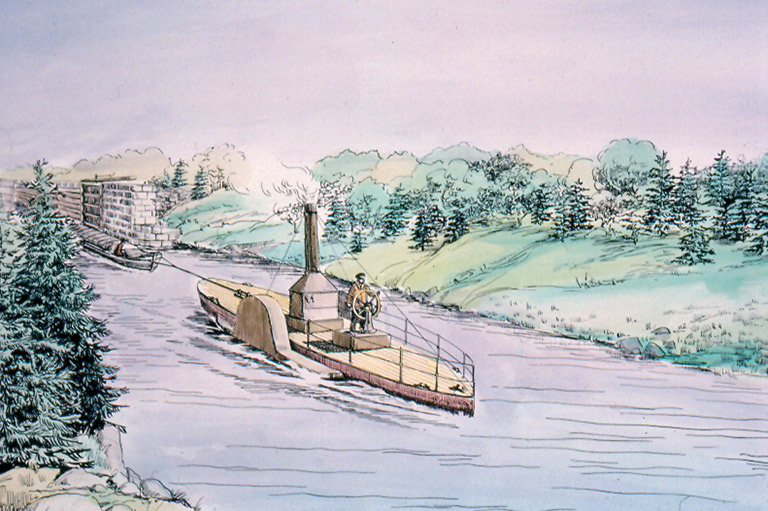

Hall suggested that a canal be built with nineteen locks at a total cost of 55,344 pounds. His vision of steam-powered tugboats hauling boats brimming with goods captivated Haligonians.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In 1826, the Shubenacadie Canal Company was formed with the financial backing of several prominent Nova Scotia businessmen, including beer baron Alexander Keith, shipping magnate Samuel Cunard, and banker Enos Collins, a former privateer during the War of 1812.

Alas, the canal plan quickly went off course. Construction ran over budget and was plagued by shoddy workmanship, particularly on the stone locks that assisted boats in bypassing sections of waterway with steep elevation changes. Designed for a warmer climate, the locks crumbled due to the freeze-thaw cycle of Nova Scotia winters.

The canal company’s president, Charles Rufus Fairbanks, sailed to England in search of more funding. But the problems persisted. In some places, the canal veered badly from its designated route. In others, the locks were built too narrow to permit the passage of certain boats. By 1831, the money had dried up, forcing the Scottish and Irish immigrant labourers to quit due to the lack of payment.

It was all quite scandalous, and the canal company was flooded with bad press. Funders, including the British government, called in their loans. By the end of the decade, everyone assumed that the canal was dead in the water — everyone, that is, except Charles Rufus Fairbanks’s son Charles William Fairbanks.

The younger Fairbanks watched as his father fruitlessly tried to revive the canal and then died in 1841 with the project uncompleted. Studying engineering in Britain, Charles William returned to Nova Scotia in the 1850s intent on salvaging his father’s legacy. In 1854 he bought the land along the canal route and relaunched the project — this time using construction techniques designed to survive North American winters.

His plan called for only nine locks, not nineteen. He also incorporated a relatively new technology — the marine railway, which enabled users to load boats onto specially designed rail cars, called cradles, and transport them overland from one section of waterway to another. The younger Fairbanks estimated the cost of completing the canal to be 17,250 pounds.

As we make our way through Shubie Park, we stop to inspect the fruits of his efforts. Lock 3 and Lock 2, located close to where the canal meets Lake Micmac, remain intact after more than a century and a half — a testament to the talents of the stonemasons who built them.

Compared to the first attempt at constructing the canal, the second phase was smooth sailing. By 1857 much of the canal system was complete, and, after the final installation of the marine railways, the first cross-colony trip from Dartmouth to the Bay of Fundy was made by the steamer Avery in November 1861.

Unfortunately for Fairbanks, redemption for his father was ultimately thwarted by the iron horse. As workers were putting the finishing touches on the canal, a rival transportation company, the Nova Scotia Railway, was working to build a rail line between Halifax and the Annapolis Valley community of Windsor on the Bay of Fundy.

Unlike canals, which froze in winter, the train operated year-round, and it could make the trip from Halifax Harbour to Fundy tidewater in a fraction of the time. The Shubenacadie Canal, touted as a cash cow, turned out to be a white elephant. It fell into financial ruin and by 1870 had ceased operation.

For most of the twentieth century, the canal lay abandoned and largely forgotten. But in the 1960s Dartmouth’s civic leaders began to explore ways to repurpose the canal as a recreation and tourism draw. In 1977 the community proposed the creation of Shubie Park. Fairbanks Centre opened to visitors a decade later. Today Shubie Park boasts a fully serviced campsite, extensive hiking trails (including a section that is part of the Great Trail that spans Canada), and two beaches, one of which is supervised for swimming. In winter, the park offers more than nine kilometres of cross-country ski trails.

At the Fairbanks Centre, staff are happy to show us the model of the canal as well as artifacts recovered by archaeologists along the canal route. The park is run by the Shubenacadie Canal Commission, a charity established by the provincial government to oversee the enjoyment and preservation of the canal system waterway.

As our visit winds to a close, I can’t help but ponder the irony of the Shubenacadie Canal. Built to maximize the profits of Halifax’s business elites, it has ultimately enriched the lives of all citizens of the greater Halifax region — not by increasing their cash flows but, rather, by offering them a scenic and serene respite from the rat race of modern city life. And that’s something you can’t put a price tag on.

IF YOU GO

GETTING THERE: Shubie Park is located just off Waverley Road in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Follow the signs for the Fairbanks Centre. For public transit, head to the Bridge Terminal in downtown Dartmouth and catch the No. 55 Port Wallace bus to the park.

EXPLORE: The park features several significant historical canal features, including Lock 2, Lock 3, and the Deep Cut, a portion of canal that was carved and hacked with great effort out of granite bedrock.

WATCH FOR: Shubie Park is home to a variety of wildlife, including ducks, birds, squirrels, turtles, deer, and beavers.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History and its partners offer unique, history-based tours at home and abroad throughout the year.

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with crucial resources by offsetting the cost of running our education and awards programs.