Roots: Say it ain’t Faux!

In May 1928, newspapers across Canada reported that a consortium from York County, New Brunswick, had funded one of its number to sail to London to pursue its claim to the estate of Sir Francis Drake. You might think this odd, because Drake had been dead for 332 years, but to the claimants the huge elapsed interval was a positive boon in that it had allowed compound interest to work its magic.

Notwithstanding the British Foreign Office’s flat denial of the existence of an unclaimed Drake estate, rumours persisted that its contemporary value exceeded $100 billion, a patently impossible sum many times greater than the United Kingdom’s GDP.

Such practical thoughts hardly quelled the ardour of prospective inheritors, which also included other New Brunswickers from Saint John. As with conspiracy theories today, official denials and procedural dead ends were interpreted — to the degree they were heeded at all — not at face value but as evidence of bureaucratic incompetence or cover-up.

The Canadian experience was but a small annex to a much grander edifice of greed, deceit, and self-deception that would only be dismantled after the United States Postal Service prosecuted organizers for mail fraud. The essence of such scams is that the bad guys falsified or misrepresented historical records with a view to soliciting — and pocketing — funds from prospective heirs: the sale of shares in the estate, ongoing legal and research fees, and genealogical services, all handsomely priced.

Oscar Hartzell, the propagator though not the creator of the Drake scheme, was convicted in 1934 in Iowa, the birthplace and epicentre of the enterprise. Despite being sentenced to ten years in Leavenworth Prison, Hartzell was defended to the end of his days by tens of thousands of his dupes who were convinced that he was the real victim — a truth seeker unfairly hounded by misguided or nefarious authorities.

The Drake hoax was just one of dozens of estate claims that occupied the North American popular imagination, the courts, and the newspapers from the late eighteenth century through the first decades of the twentieth century, even inspiring an 1892 satirical novel by Mark Twain, The American Claimant.

Not all of these cases were frauds.

Entirely on the up and up was the successful 1858 acquisition of the Shard estate in Britain by the meticulously well-prepared Vermont genealogist, Columbus Smith. With a value of a mere $300,000, this claim fell several digits short of scamworthiness, but it inspired would-be heirs and scheming con men to pursue other estates for decades to come.

As François Weil has pointed out in his magnificent Family Trees: A History of Genealogy in America, hoaxes were easily propagated because there was a triple level of uncertainty about any claim: the existence of riches, the legal basis for a suit, and the determination of rightful heirs.

Successfully fudge just one of these three links, and the rest of the chain could appear compellingly strong. In the Drake case, as an example, an invented American heir was all that was needed to sustain a decades-long delusion.

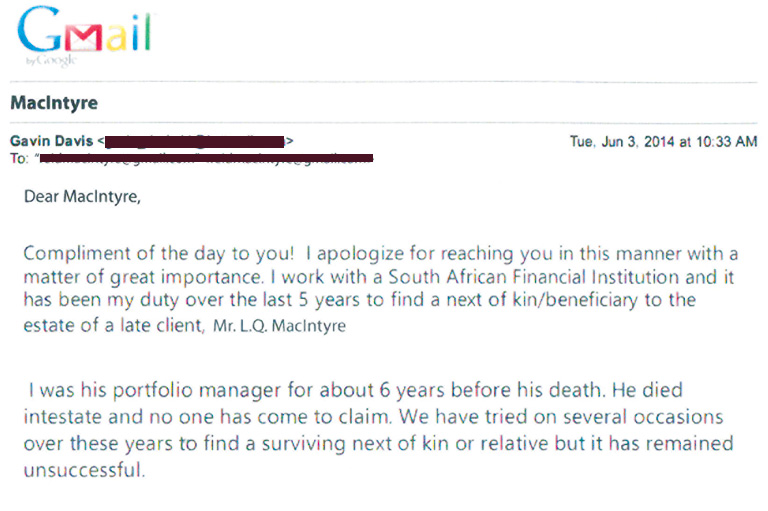

Why is this on my mind today? Well, I’ve recently received an email inquiring whether I might be a beneficiary of the late South African H.S. Jones.

My correspondent, a Gavin Davis, reports that Jones died five years ago a wealthy man with no known next of kin. Davis, who uses a Hotmail address and purports to represent a major but unnamed financial institution, is charged with finding the rightful heir and suggests I get back to him as soon as possible.

With a name like Jones, how could I not be related?

Of course there will be unavoidable costs to document my claim and make necessary legal filings. I accept that. But these will be but a tiny investment in comparison with the vast estate that will soon be mine. And maybe for a small finder’s fee — nothing extravagant, you understand — I might be able to get you in on the action.

* * *

A postscript to my June-July 2014 Roots column, “Name games”: In my last column I scolded Ancestry.ca for the misleading depiction of family history research presented in its TV advertising. Well, fair’s fair. The most recent wave of Ancestry commercials, focussing on researchers and their enthusiasms, is tone perfect and lovingly crafted. Bravo!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!