Untold Stories

When Europeans first arrived in the New World, they were interested in the treasures the land might hold. Known to some Indigenous people as Turtle Island, the land was rich with resources and filled with people. Indigenous peoples had been living and trading on the territories with each other for as long as anyone could remember.

Groups would trade items like corn, dried fish, or furs, as well as beads, shells, and other goods. Trade included the idea of gift giving to help make sure that everyone was showing and being shown respect. Gift giving also helped to confirm alliances. Trading was based in respect and good communication.

Many Europeans who came to what we now call North America to trade were interested in the abundant resources. Those resources, in turn, fuelled much conflict between England and France.

In 1706, Jesuit missionary Pierre-Gabriel Marest reported on the trade growing out of the first meetings between Hudson’s Bay Company traders and the Indigenous peoples who lived around the Hudson Bay region:

“The English Merchants, in order to profit by the voyages and discoveries of their fellow countrymen, have since then made a settlement at Hudson’s bay, and have begun there a trade in furs, with many northern Indians — who during the long summer come, in their pirogues, on the rivers which empty into that bay. At first, the English built only a few houses, that they might pass the winter in them and await the [Indigenous trappers]. They had much to suffer, and many died there from scurvy. But, as the furs that [they] bring to that bay are very fine, and as the profits on them are great, the English were not deterred by the inclemency of the weather or the severity of the climate.”

Beaver pelts were among the most sought-after furs due to the popularity of beaver top hats in Europe at the time. While the hunting of beavers was only a small part of life for Indigenous peoples before Europeans came, it soon became the predominant activity in some territories.

Beaver pelts were too small to stretch across frames to make Indigenous homes and were not well-suited for clothing, but Europeans could not get enough for their own markets.

Indigenous people also traded other less-valuable pelts with Europeans at posts located throughout the continent, including in the interior. These furs included otter, muskrat, mink, fox, raccoon, deer, moose, and bear.

The focus on beaver trapping had many important impacts on Indigenous peoples. For example, in some areas declines in local beaver populations increased conflict among Indigenous peoples. In addition, beginning in the nineteenth century, a decline in the popularity of beaver hats gradually lowered the price for pelts. This meant that trappers received fewer goods in exchange.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Chief Trader John Haldane of the Lake Superior District wrote in 1823–24 of the hardships caused by a dwindling of beaver, bear, and other fur bearers in the region: “The scarcity of those animals is greatly felt by the Indians. ... In the summer and fall the Indians are furnished with Nets and in the fall they are supplied with a good stock of ammunition. Notwithstanding these supplies they are often necessitated to have recourse to the establishment when we give them fish, potatoes & Indian corn. Humanity & Interest compel us to be kind to them, & they are generally grateful to us.”

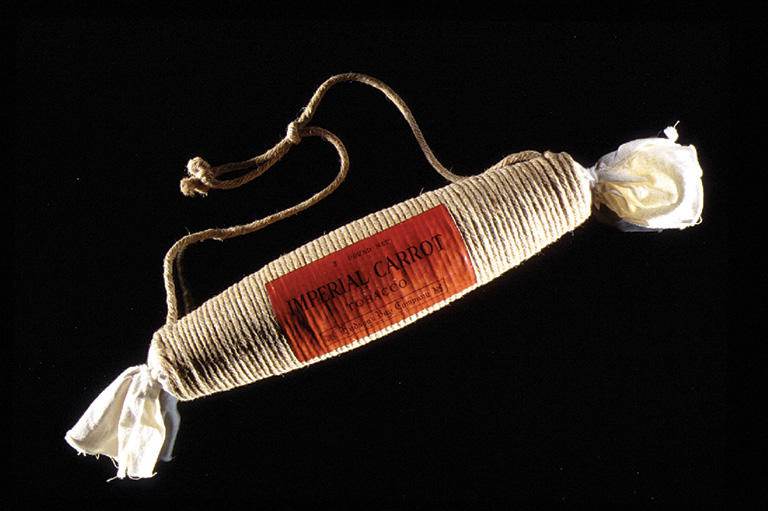

In addition to trapping, Indigenous peoples often worked in and around European forts, supplying the occupants with meat and fish or helping to haul furs. In exchange, they received European-made items such as kettles, knives, axes, pots, cloth, needles, glass beads, and blankets. The Europeans often also offered alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and ammunition.

The trade relationship changed the lives of Indigenous peoples in both positive and negative ways. At least at first, Indigenous people were able to control the trade, because it depended on their trapping.

But the fur trade made some Indigenous peoples dependent on European goods. While some groups profited from the new interactions, others became victims of new diseases and unfair trading practices that placed them at a disadvantage.

Most histories of the fur trade have been written as the stories of men. Women, if they appear at all, have been portrayed as background actors. However, more recent research has revealed that the fur trade was not only a business but also a social and cultural system with women at its very core. Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women played key roles in the trade and saw themselves as active participants.

Indigenous women supplied the trade with food and goods, worked as traders alongside men, and also cemented trade and personal relationships through marriage.

Unions between Indigenous women and European traders were often seen as symbols of friendship and of alliance. In addition, Indigenous women were active in day-to-day tasks like producing food, clothing, and staples like wild rice and maple syrup, as well as in snaring game.

Matonabbee, a Dene guide who travelled with HBC explorer Samuel Hearne in the eighteenth century, urged Hearne to take Indigenous women with his teams on their journeys.

In his 1771 journal, Hearne quotes Matonabbee as saying of women, “One of them can carry, or haul, as much as two men can do. They also pitch our tents, make and mend our clothing, keep us warm at night; and in fact there is no such thing as travelling any considerable distance, or for any length of time, in this country, without their assistance.”

The unions of Indigenous women and European men also created the people today known as the Métis Nation, which developed a unique history and culture.

Centred around the Red River region of modern-day Manitoba, Métis society was deeply connected to the fur trade, with the men trapping and transporting furs and women producing trade goods like clothing — which included their beaded designs — along with pemmican, a vital source of protein.

Before 1821, fur trade marriages were not recorded by Christian churches. Instead, almost all of the officers of the major trading companies were married a la façon du pays to Indigenous women.

These “country marriages” were ceremonies that combined Indigenous and European customs. They were performed mostly because missionaries were not common in fur trade country at the time.

While some men honoured their Indigenous wives, journals documenting life at trading posts also reflect a growing concern over traders abandoning their country wives, as well as the obligations claimed against HBC because of this.

In part due to such obligations, and with HBC having by then cemented alliances with First Nations groups, after 1800 most traders were encouraged to marry European or sometimes Métis women from within the Company.

Christian churches also started to require that all marriages, even country marriages, be conducted by a missionary and recorded by the churches, further delegitimizing earlier unions — as well as the children resulting from them.

The 1830s saw more European women immigrate to North America. Many married HBC officers and played valuable roles by managing family affairs, strengthening relationships, and, sometimes, working as teachers in the Red River Colony.

The Rupert’s Land transfer of 1869 had a tremendous impact on the Métis and other Indigenous groups in the area.

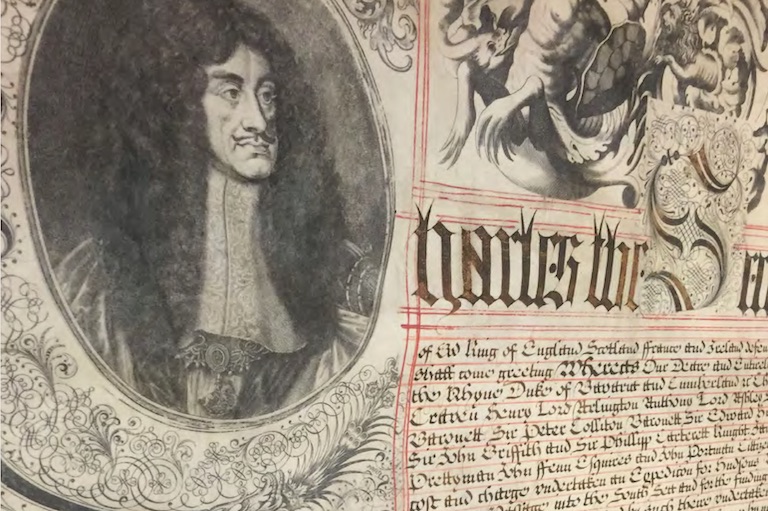

HBC had ruled Rupert’s Land since it was given to the Company via Royal Charter in 1670. However, by the 1800s, the region was home to a thriving Métis Nation centred around what is now Winnipeg.

The fledgling Dominion of Canada, led by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, wanted to annex Rupert’s Land for two main reasons: to secure land to build a railway to British Columbia and to prevent the vast region from falling into American hands.

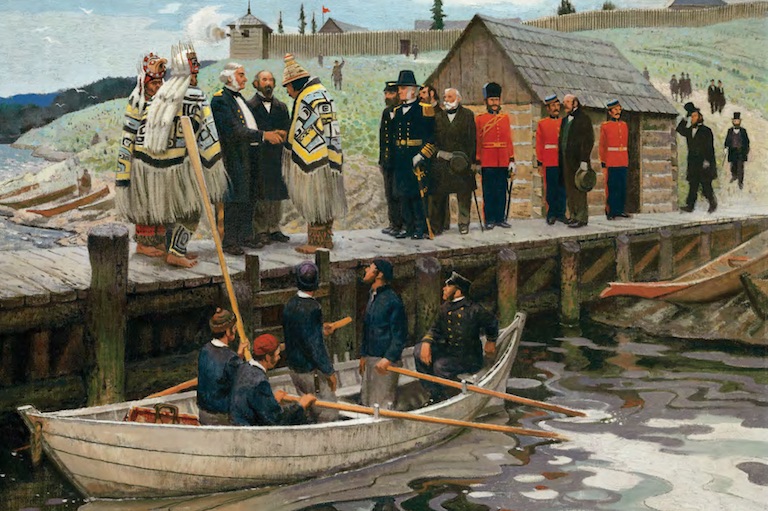

In 1869, HBC agreed to transfer most of Rupert’s Land to Canada — but the deal was cemented without input from the Métis or the non-Indigenous settlers at Red River, or from any First Nations in the vicinity.

There were no land titles or surveys for the lands in Red River, and residents were angry and fearful that the Canadian government would break up their farms. Their concerns grew after a Canadian survey party arrived in October 1869 without warning and began to lay out lines that cut across existing farms.

The government of Canada had also appointed a new governor for the region, William McDougall, who did not like Catholics or francophones.

Regarding McDougall, Macdonald had written to his colleague George Brown, saying, “I anticipate that he will have a good deal of trouble, and it will require considerable management to keep those wild people quiet.”

Indeed. When McDougall arrived at Red River in November 1869 to take control, he was turned away at gunpoint by the Métis, who were led by their charismatic leader Louis Riel. The Canadian government was not able to take control of the territory on December 1, as had been planned.

The Métis wanted a representative government that would respect their rights. To stake their claims, a convention of Red River residents met in November 1869 and proclaimed its own government, with Riel as leader.

The new provisional government was supposed to speak to the Canadian government about how the settlement would enter Confederation while still protecting the rights of the people living there.

Locals also took over Upper Fort Garry (located near The Forks at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in what is now Winnipeg) to show their resolve. Their actions became known as the Red River Resistance.

The tiny province of Manitoba entered Confederation in 1870 with an agreement that Canada would protect Catholic and francophone rights. This agreement also included lands for the Métis and settlers in territory, though many people never received the land promised to them.

In addition to the political settlement, the Rupert’s Land purchase had other important consequences. It encouraged the Canadian government to enter into treaty negotiations with Indigenous peoples within the territory and led to the signing of the first numbered treaty, Treaty 1, in 1871.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!