A Silk for a Pelt

It was the summer of 1723. Madame Marie-Anne Catignon, a thirty-four-year-old merchant based in the port city of La Rochelle, France, sent a series of letters across the Atlantic Ocean to her correspondent in the colonies. In the letters, she provided her Montreal trading partner, fifty-two-year-old Madame Marie-Louise d’Argenteuil, with a detailed statement of account, including payments related to trade in beaver pelts.

Catignon went to great lengths to explain why she had sent her colonial counterpart a shipment of fine fabric that was not exactly what d’Argenteuil had ordered: “You will perhaps be surprised to see the damask from Tours, instead of from Lyon, which you requested. I ordered it from Lyon at the price you set, but instead of [the fabric for] two outfits, they only sent [enough for] one. ... I did not think it would be correct to send you such expensive fabric, and I kept it. This is what obliged me to order the fabric from Tours, which is usually not as expensive. … I hope you will be happy with what I have sent.”

Catignon also apologized that she had been unable to fulfill certain orders: “I was quite mortified, Madame, not to have been able to send you the merchandise this year, since my husband had made undertakings that could not be executed.” She concluded her correspondence: “Please be assured of my goodwill toward you and that I am, madame, your most humble and obedient servant, the wife of Catignon.”

The relationship between Catignon and d’Argenteuil was a long-standing business partnership and friendship and one of the many examples of female enterprise at the heart of New France’s fur trade — from the Indigenous women who hunted, processed, and transported the furs to trading posts, to the European and French-Canadian women who acted as traders, merchants, and shippers.

“Women had a major involvement in the trade in furs in the St. Lawrence valley and its hinterland,” writes University of Toronto professor emeritus Jan Noel in Along a River: The First French-Canadian Women. “Female economic production and exchange was in no way exceptional in pre-industrial societies. The economically active women in New France … were, in large degree, simply part of a transatlantic norm.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The fur trade’s importance in the history of New France cannot be overemphasized. It was what originally attracted colonists to the St. Lawrence River valley, and it quickly became the bedrock of the colonial economy. As furs, fur-trimmed clothing, and broad-brimmed beaver-felt hats became staples of European fashion in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the depletion of European beaver stocks increased the importance of the colonial fur trade. Long-standing European rivalries were transferred to the colonies, and the English, French, and Dutch competed for access to North American peltry.

The fur trade was not a static industry over the course of the New France period, explained Jean-François Lozier, curator of French North America at the Canadian Museum of History. Rather, it was a complex system influenced by evolving geopolitics, colonial relations, Indigenous alliances, and shifting market conditions.

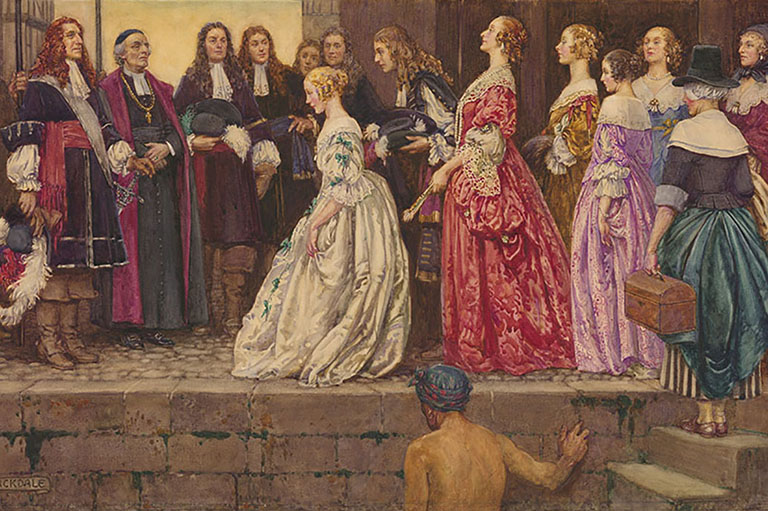

There were many players involved in the trade. We might picture “rugged trappers in buckskins” and “managerial gentlemen in top hats,” writes Noel, but this is an incomplete image. Sisters, wives, and daughters of merchants, military officers, and political officials were involved in the trade. Likewise, Indigenous people were active participants in the transatlantic market economy: The French relied on Indigenous men and women to hunt fur-bearing animals and to process the furs. Washing the furs, scraping off the dirt, flesh, and blood vessels, and stretching them over wood frames to dry “was women’s work in Indigenous societies,” said Lozier. Indigenous people also influenced production as consumers by demanding certain goods, and pitted the French and English against each other, forcing them to lower their prices and to improve their merchandise.

Indigenous women, along with men, played a key role in carrying the pelts to the points of trade, often undergoing long and strenuous journeys. Then they bartered the furs with French traders for goods like iron tools and wool blankets. “For these French traders, knowing Indigenous languages, being familiar with Indigenous cultures and cultural conventions, was crucial,” said Lozier. “Trade and diplomacy go hand in hand.”

In many instances, French traders married Indigenous women, who then acted as important mediators and translators. Whether through a church-sanctioned union or via a mariage à la façon du pays (country marriage), as unofficial unions were called, these marriages brought French traders into Indigenous communities and integrated them into the kinship networks of the fur trade.

Some women who worked at the forts, even if they weren’t primarily fur traders, exchanged their labour for payment in furs and hides. At the mission of the Hurons at Detroit, Father de la Ricardie and Pierre Potier recorded in a journal entry that a certain Madame Goyau “began to do the laundrywork and baking for this mission, on St. Michael’s day, 1743, for the sum of 100 livres per annum.” The entry records that the payment of her salary included “45 livres in deerskins [and] 40 livres less 5 sols in castors [beaver skins].”

After the animal pelts were brought to the French trading posts and transported from there to the colonial centres of Quebec, Montreal, and Trois-Rivières, merchants shipped them onward to French ports like La Rochelle, Bordeaux, and Rouen. From there, the furs ended up in various markets, transformed in shops into hats and clothing, not just in France but across Europe.

It was in the trading ports at the nexus between New France and France that merchants like Catignon and d’Argenteuil conducted their business, often deriving more profit from the trade than did the hands-on workers who harvested, processed, and transported the furs.

Born in France in 1688, Marie- Anne Busquet was twenty-five years old when she married Jean-Jacques Catignon, a first-generation Canadian merchant in his early thirties. Jean-Jacques divided his time between Quebec and La Rochelle, where he maintained strong family ties. As his wife, Marie-Anne was involved in the transatlantic trade, first from the Catignon base in Quebec for about a decade, and then in La Rochelle for several years.

From the letters she left behind, transcripts of which are preserved in Library and Archives Canada, Marie-Anne Catignon emerges as a savvy and meticulous businesswoman. In her correspondence with d’Argenteuil, she quickly gets down to business, carefully settling accounts, astutely comparing prices, and noting the transport of products on royal versus merchant ships — an important distinction due to the beaver duties collected at the port of entry and the differences in shipping charges on Crown and private vessels.

Nor was Marie-Anne the only woman in the Catignon clan to take part in the trade. When Jean-Jacques was away from Quebec, his sister worked alongside his wife for the family firm, as letters and bills of lading signed by Madame and Mademoiselle Catignon attest.

For example, a 1721 bill of lading records red wine, bales of fabric, cases of soap, and a barrel of plums heading Madame Catignon’s way in Quebec from Bordeaux; in return she owed 1,737 livres in bills of exchange and in fur — the skins of 150 martens, 620 bears, 24 seals, 231 otters, 127 red foxes, and 28 timber wolves. According to historian Kathryn A. Young, whose important research on the transatlantic trade brought the activity of these mercantile families to light, this was a common means of payment for colonial merchants.

According to Noel, the property laws in France and in New France during the ancien régime — a period spanning from the late Middle Ages until the French Revolution of 1789 — were relatively conducive to female inheritance and participation in economic activity. This was especially true for widows of New France, who, according to the Custom of Paris — a French legal code dating from the sixteenth century — were legally entitled to a half share of their husband’s property and enterprise, regardless of his intent. Likewise, daughters were not supposed to be deprived of an inheritance equal to that of their brothers. This contrasted with the situation of women in the Thirteen Colonies of what’s now the eastern United States where, under English common law, inheritance usually passed down automatically to the oldest male heir, and a widow’s provisions depended on her husband’s goodwill.

There were therefore many French wives who participated in the family venture — whether in the fur trade or otherwise — and who carried it on after the deaths of their husbands. A business letter addressed to “Widow Catignon” in 1726 indicates that Marie-Anne Catignon was one of them. Her sometime trading partner, Marie-Louise d’Argenteuil, was another.

Marie-Louise Denys de la Ronde was sixteen in 1687 when she married twenty-eight-year-old Pierre d’Ailleboust d’Argenteuil, a high-ranking lieutenant from an upper-class New France family who participated in various military expeditions and led several fur-trading convoys. Together, they had eight children.

Eventually, Marie-Louise asked for a separation of goods from her husband due to his mismanagement of affairs. After his death in 1711, she engaged in a lengthy legal battle with the Sulpicians — an order of missionary priests with vast seigneurial holdings in New France — over claims to the Argenteuil seigneurie, a large tract of land that had been granted to her late husband’s father in the previous century. Ultimately, she was successful in the land dispute.

As a widow, d’Argenteuil participated in the fur trade for several decades with her sons, who were stationed in Quebec, as well as in Louisbourg on Île Royale (present-day Cape Breton Island), in Toulouse, France, and in France’s Caribbean colony of Martinique. She later entered business with a tanner, with the understanding that she would supply the animal skins. At her death, she left behind a fortune: Her assets totalled more than 46,000 livres, about 150 times the average annual salary of a skilled tradesman in New France.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

The fur trade in New France was not a free trade by any means. At various times the French Crown attempted to control the trade by granting monopolies to specific merchant companies that were committed to promoting French colonial interests. By the late seventeenth century, a limited system of granting fur-trading licences was instituted. By the 1690s, King Louis XIV ordered the immediate closure of all but a handful of sanctioned trading posts.

It was illegal to export beaver furs anywhere but to France, but this certainly didn’t stop such exports from happening. An illegal trade route was active throughout this period between New France and the English and Dutch colonies in eastern North America, running primarily between Montreal and Albany, New York. At one point, even the respectable Madame Marie-Louise d’Argenteuil was suspected of diverting furs to the black market, since the seigneurie she inherited from her husband was located in a prime spot for intercepting shipments of furs bound from the backcountry toward Montreal. Her accusers cited the facts that the land of the seigneurie had not been cleared, and that her children learned more about fur and Indigenous languages than about agriculture, as evidence of her illicit activity. According to Noel, notarial documents from the time seem to confirm their suspicions.

It is difficult to quantify the illegal trade, but some estimate that in the early years of New France the illegal export represented roughly half to two-thirds of the total quantity of beaver pelts produced in Canada each year. During the later years, a lack of documentation makes it impossible to quantify.

At the heart of the contraband trade in the eighteenth century were the three daughters of a Montreal merchant: Marie Magdelaine, Marie Anne, and Marguerite Trottier-Desauniers. They learned the ins and outs of the trade from their father, Pierre Trottier, and became skilful merchants themselves. Their brother, Antoine Trottier-Desauniers, made his mark in maritime trade and shipbuilding.

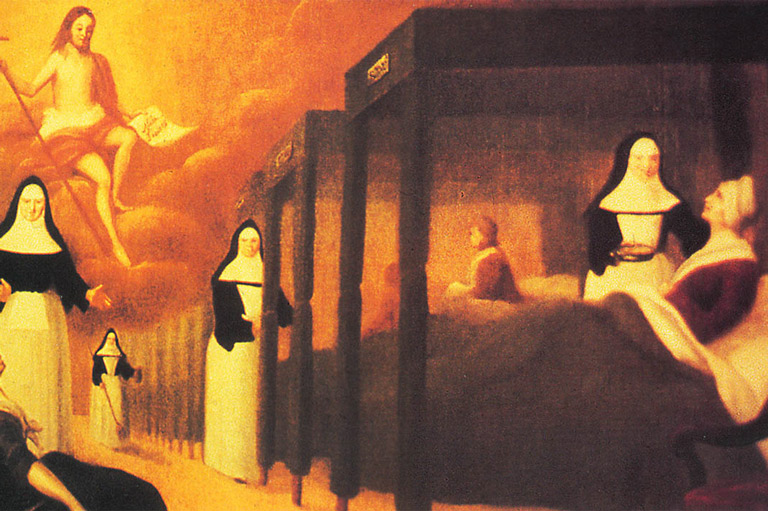

The three sisters never married and instead banded together to set up a shop in 1727 in the French and Indigenous community of Kahnawake, southwest of Montreal. Like other missions, Kahnawake, or Caughnawaga, was divided between the Church, the army, and the fur trade and consisted of a chapel, fortifications, and storehouses. At first, their shop was innocent enough, supplying clothing to Indigenous people. But soon, the demoiselles Desauniers, as they were known, had their hands deep in the contraband trade. With their shop as a headquarters, they ran smuggling operations in collaboration with the Iroquois (Mohawk) people who lived at the mission as well as with the missionaries themselves, such as their Jesuit business partner and friend, Father Tournois. Skilled entrepreneurs, the sisters spoke Indigenous languages and cultivated efficient networks of business partners.

They carried on this way, undisturbed by the authorities, for years. David Ledoyen of Parks Canada, part of the curatorial team responsible for an exhibition on the illegal fur trade at the Fort Chambly National Historic Site in Chambly, Quebec, explained that the sisters’ black-market activity was tolerated because it was highly profitable and benefited their community. The sisters had friends in high places and were able to avoid the controls of the authorities. The Jesuit missionaries with whom they colluded were more than happy to receive part of the profits, which they reinvested in their college and church, thereby funnelling the money back into Kahnawake’s services and infrastructure.

Even when agents from the powerful, royally backed Compagnie des Indes began to question the activity of the Desauniers sisters and other contraband traders, they had to tread carefully to avoid antagonizing France’s Indigenous allies who were involved in the illicit trade.

“They were apparently famous liars,” said Noel, who refers to the Desauniers sisters as “spicy” characters who left a colourful mark on history. “They kept procrastinating when they were supposed to close down their shop.” Finally, in 1750, a change in the political landscape triggered the temporary expulsion of the three women and their Jesuit partner to France. Though the sisters attempted to wiggle their way back into the trade, they officially closed shop in 1752, after twenty-five years of flourishing contraband commerce.

While their story is perhaps the most extraordinary, the Desauniers sisters were not the only women involved in the contraband fur trade. Despite attempts to put an end to it, deerskins, muskrat furs, and, most of all, beaver pelts, travelled 350 kilometres south from Montreal into the hands of English and Dutch traders in Albany, New York, right under the noses of the authorities, often concealed in the baskets of Indigenous women.

Robert Sanders, a merchant and sometime mayor of Albany, kept a letter book in which he recorded many details of the illegal trade. Of the six usual carriers he hired, he named two Indigenous women. First, there was Marie-Magdeleine (only her Christian name is recorded), whom he described as having an impediment in one eye. Comments she made to Sanders that she knew one Montreal merchant “well” and another one “perfectly well” indicate that she was firmly integrated into the French trade network.

The other female carrier Sanders mentions was a Mohawk woman named Agnesse (he only recorded her Christian name), who lived in Kahnawake, where she cultivated fields of corn, squash, and beans with her daughters and other women. She often travelled south to visit relatives in the Champlain Valley, taking the opportunity to carry smuggled goods. In the fall of 1752, Sanders recorded that Agnesse carried various goods, including beaver and sugar. Later that spring, he mentioned that Agnesse carried a packet of beaver skins. Between May and July 1753, it is recorded that she made the trip of more than three hundred kilometres between Kahnawake and Albany three times — no easy feat.

The participation of colonial and European women in the fur trade declined after the fall of New France in 1760. Along with the British army came a supporting cast of merchants, traders, and other service providers, while growing numbers of Anglo-American merchants moved into the newly conquered territories. Many French-speaking traders left the fur trade and North America altogether. Those who stayed were forced to deal with England, rather than France, and were thus at a disadvantage due to barriers of language and culture. Sometimes French merchants managed to re-establish themselves by cultivating partnerships with the new Anglo-American merchants who had moved into the major centres like Montreal and Quebec City. But, as historian Michael Payne notes in The Fur Trade in Canada: An Illustrated History, “after 1763, to be French-speaking meant more and more to be a company employee and not an owner.”

The illegal fur trade had its legs knocked out from under it once the British took over the colony. British hegemony on the North American continent meant that there were no longer rival European nations vying for furs, which made smuggling — work in which many women participated — no longer necessary.

The French military organization, which included alliances with influential Indigenous peoples, crumbled. French military personnel were replaced by British officers at the trading posts, and, according to Noel, the British did not typically bring their wives with them. Nor did they have the same family trade networks that were prominent in France; instead, they brought the idea of separate spheres of activity for men and women to their newly conquered colony.

But the British still needed Indigenous trading partners. Historians have shown that throughout the eighteenth century the British relied on Indigenous women to perform essential tasks at the posts, and they also performed an integral role as cultural mediators through marriage. As European women disappeared from the scene, Indigenous and Métis women continued to play a crucial part in the fur trade for years to come.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement