We Were the Lucky Ones

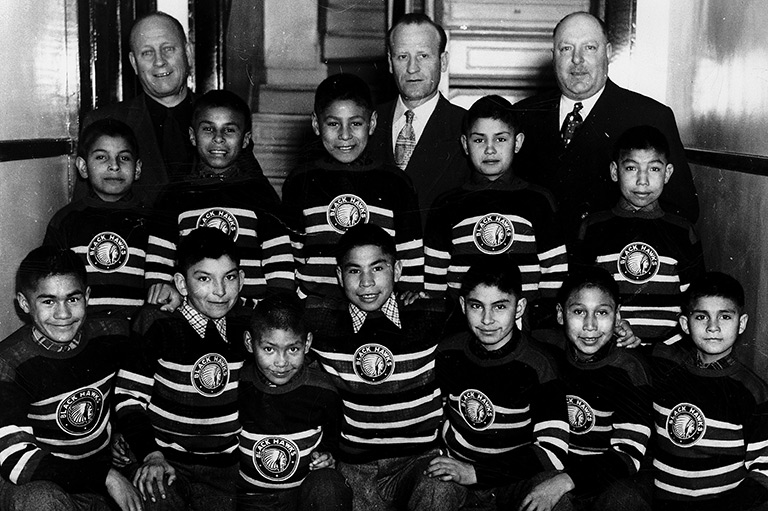

Very few people looking at the photographs of the Sioux Lookout Black Hawks on their April 1951 exhibition tour would disagree with the first part of Kelly Bull’s remark: “We sure look happy,” said the Ojibway man, now in his eighties, who played on the hockey team when he attended the Pelican Lake Indian Residential School near Sioux Lookout, Ontario, as a child. The second part of his reflection, however, is more thought-provoking: “The question you should be asking is: Were we?”

The Black Hawks’ tour was an “exhibition” of the residential school system, seen through the lens of photographer Gar Lunney. The Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) partnered with the National Film Board Still Photography Division (NFBSPD) — the official photography agency of the Canadian government — to send Lunney to document the tour. His images were therefore produced with the aim of justifying the Canadian government’s policy of the time toward Indigenous peoples: to assimilate them into white Canadian society. About two dozen of Lunney’s carefully composed photos survive in private collections. To our knowledge, only one remains in the official Library and Archives Canada catalogue today. During the 1950s and 1960s, the photos of the Black Hawks, like other NFBSPD photos, could have been used in internal and external DIA publications, national exhibits, and international newspapers.

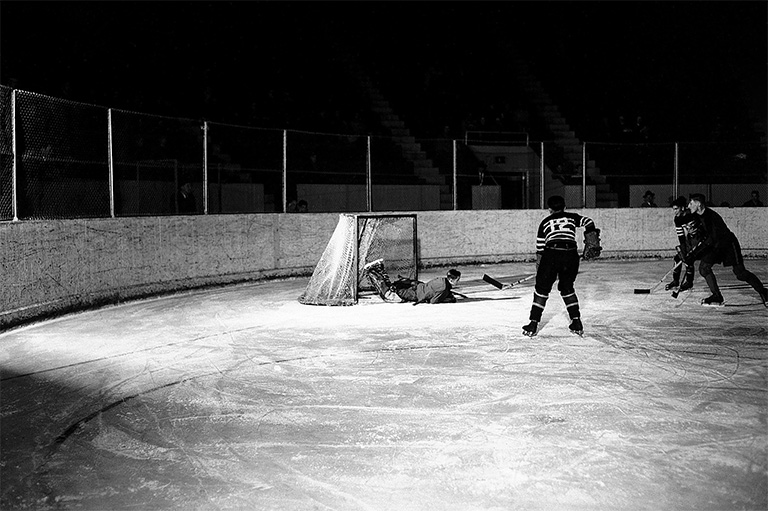

The players have unforgettable memories of the tour: playing at Maple Leaf Gardens, riding horseback at a ranch near Toronto, dining with politicians on Parliament Hill, and staying overnight at Ottawa’s ritzy Chateau Laurier. “I remember we toured the Maple Leaf Gardens,” Bull recalled. “Toronto happened to be out of town, so their dressing room was [open].… We were touching their skates, their second pair of skates, and their sweaters. It was a big deal. We were just in awe.”

What the photos don’t show is the abuse and neglect at the residential school that the players had left behind — if only briefly — during their once-in-a-lifetime tour. “Sports was my escape,” Bull reflected. “I ran away from all the negative.”

For this article, as part of a larger research project, we worked with Bull and two other former Black Hawks players — Chris Cromarty and David Wesley — to retell the story of the hockey team through the students’ perspective. The men used the photos of the 1951 tour to reclaim the images and the realities behind them. Bull is from Lac Seul First Nation (now Obishikokaang); Cromarty, who is Oji-Cree, is from Big Trout Lake (now Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug); and Wesley, who is Cree, is from Fort Albany First Nation. All attended the Pelican Lake Indian Residential School in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Pelican Lake Indian Residential School

Pelican Lake Indian Residential School, also known as Sioux Lookout Indian Residential School, was built by the federal government in partnership with the Anglican Church and began operating in 1927. The school came to be known as Sioux Lookout because it was located close to the town of the same name; its formal name stemmed from the fact that it sat on the shores of Pelican Lake, on the traditional territory of Lac Seul First Nation in Northwestern Ontario. Situated about three kilometres from a stop on the Canadian National Railway, the school housed Cree, Ojibway, and Oji-Cree students with a catchment area thousands of kilometres in size.

During the era that Bull, Cromarty, and Wesley attended school at Pelican Lake, the DIA received multiple reports about the inadequacies of the school’s facilities, curriculum, and staff. The boys basement washroom produced bad smells — perhaps, one report noted, because no disinfectant was being used. Although parents and the public believed that the schools followed the provincial course of study, older students at the school only attended class part-time. The students worked for half the day on what the school called chores, consisting of tasks such as hauling coal, scrubbing floors by hand, and hauling and chopping lumber for the school’s furnace. An inspector’s report filed on October 20, 1951, expressed concerns that the students’ insufficient diet was causing “malnutrition and monotony.”

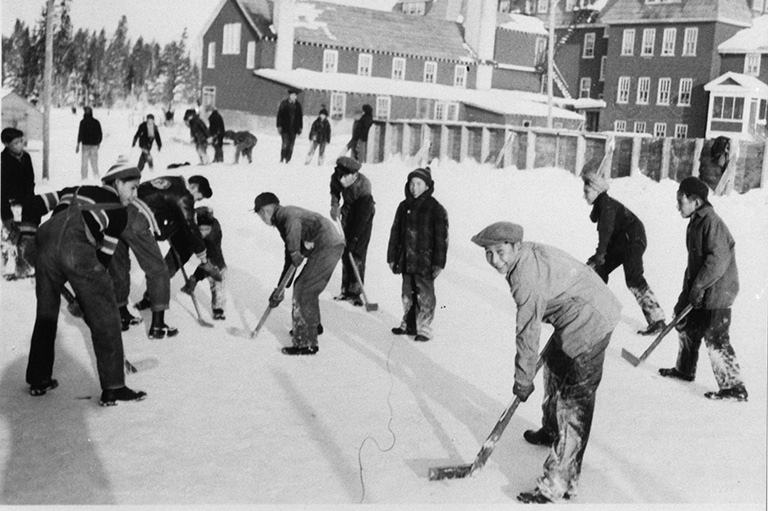

Perhaps most alarming was an assessment of both the Pelican Lake school and the Shingwauk Indian Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. The regional inspector, H.G. Mingay, considered the situation at these schools “urgent.” He compared them to the workhouses of Victorian-era England, noting, “there is no decently equipped room in which a pupil may sit down, read a newspaper or write a letter or enjoy himself in any small degree. Nothing is provided but a cement basement with wooden benches.” Mingay recommended “that the schools be closed” if the situation was not improved, concluding: “At present in many cases, Residential Schools are not a credit to the Canadian public.” The following year, Mingay reported that the overcrowding problem was so serious that converting part of the barn into a classroom should be considered. Ultimately, this suggestion was scrapped because, even with extensive renovations, it was unlikely that the odour of farm animals could be completely eliminated. Such inhumane conditions are known to have existed across the residential school system and they were surely among the reasons why the boys took to hockey. As Cromarty explained, the sport “took us away from the drudgery.”

“We were sneaking down at four in the morning... just to skate around the rink and play hockey”

— Chris Cromarty

Sports as assimilation

Wesley, Bull, and Cromarty attended Pelican Lake and played for the Black Hawks during a short period of heightened government interest in providing competitive sports to residential school students. In 1949, the DIA created a new portfolio for physical education and recreation, and it soon hired a supervisor, Jan Eisenhardt, to oversee its development. He conducted a cross-country survey of residential schools and reserve communities to determine what was needed. In general, he was disappointed that opportunities for sports and recreation were limited.

“They didn’t supply sports. So one guy asked if we could have some kind of game,” David Wesley recalled. He said the students cut and split logs to build the boards for an outdoor hockey rink. “[Supervisor] Pete Seymour, from Kenora, he was forcing them to have some kind of sports.… He used to speak to us in Ojibway, even though he wasn’t allowed.”

During the short period that he was employed by the DIA, Eisenhardt campaigned for more money for sports programs in the schools and on reserves. He knew that physical activity was good for health, but he also believed that sport and recreation would help to ease the path of Indigenous people towards assimilation by providing them with opportunities to engage in activities at which he thought they naturally excelled. Like many of his contemporaries at the DIA, Eisenhardt was convinced that he youth had the most potential for change. He believed that the students (in particular the boys), after having learned the desired values and behaviours at residential school, could return to their reserves and be a good influence there, teaching their family and friends how to play, compete, and live like white men.

The Anglican Church made a similar argument in a 1940 report on the Sioux Lookout school: “Unlike their playmates of civilization, the Indian children’s recreation must be cultivated and developed, as they lack the knowledge of creating their own amusements” and had to be taught appropriate ways to spend their leisure time. Privately, school officials wrote in correspondence to each other that hockey helped with order and discipline at the school, and they commented that fewer boys had been running away from the institution. In a summary of the Black Hawks’ 1948–49 season, they explained their reasoning for starting the team: “The main object was to teach the Indian pupils good clean competitive sportsmanship and to boost the morale of the school which was somewhat low at this particular time.”

“We’d never been at a white peoples table. It was different. You didn’t want to chip something.”

— David Wesley

The Black Hawks’ winning season

In their 1949–50 season, the Black Hawks won the Sioux Lookout and district championship and went on to win the Thunder Bay district championship. They were honoured at a Rotary Club luncheon with a public trophy presentation and a short speech by the district’s Indian Agent, Gifford Swartman, who was heavily involved with the team. For years, Swartman had been advocating for better recreation at the school to develop “character and physique.” Eisenhardt was also present and spoke about the DIA’s new directions in physical education and recreation.

For both the Pelican Lake school’s Anglican administration and the DIA, the Black Hawks were an opportunity to showcase the success of the residential school program. In a handwritten report dated May 1950, Eisenhardt remarked: “I am sure, by the way people are talking [about the Black Hawks], that many, who perhaps previously had held rather low opinions about the Indians, were changing their ideas, realizing that given opportunities the Indian children and adults could achieve something.” According to a summary of the team’s first two seasons, the boys made “a very fine name for themselves and brought honour as well as a considerable amount of publicity to the school and town.”

The boys of the Black Hawks dazzled arenas in Northwestern Ontario, as well as in Ottawa and Toronto, with their pure, never-say-die style of play. David Wesley, who went on to play semi-professionally, is often referenced in newspaper accounts as a standout player. Their conduct impressed spectators and reporters alike, because they rarely received penalties and were polite and well-behaved off the ice as well. Newspapers such as the Sioux Lookout Bulletin heaped praise upon the boys for their successes and their sportsmanship, especially their teamwork and “clean” style of play — a welcome change from how rough the sport was becoming. Their teamwork might have been especially notable because, in the post-Second World War era in which the Black Hawks played, learning teamwork was seen as an important part of boyhood in Canada. It aligned with the government’s attempt to unify the country and to keep the male population fit for fighting.

For the players, hockey was a lifeline that served as a temporary escape from their lives at the institution. During tournaments, the boys had nights away from the school and a break from their tiring physical labour. When playing in other towns, they experienced staying in hotels for the first time and had plenty to eat. The boys got to meet, and learn from, former New York Ranger John “Jack” McDonald, who had moved to Sioux Lookout after his NHL career and was playing for an amateur team sponsored by the local branch of the Royal Canadian Legion.

In competition, hockey matches were a chance for players to prove themselves by taking on, and usually beating, white teams that had much more experience, better equipment, and better facilities. Hockey was a welcome challenge and a source of pride for the boys, who had previously had to make do with cardboard for toboggans. The hockey players were also the few students at the school who had regular recreational programming and facilities, despite the new competitive-sports agenda encouraged by Eisenhardt. In a 1951 report, Anglican Church officials stated that no summer sports equipment had been provided by Indian Affairs. As Kelly Bull explained: “We were the lucky ones.”

The Black Hawks 1951 tour

In the winter of 1950, Paul Martin Sr., federal minister of health and welfare, and Percy Moore, director of Indian and northern health services, travelled to Sioux Lookout to officially open a new Indian hospital. During their visit, Martin and Moore attended a Black Hawks exhibition game. Martin was so impressed with the team that he began to work in co-operation with the minister of citizenship and immigration — whose portfolio included the DIA — to organize a hockey tour to Ottawa and Toronto for April 1951. In addition to that Southern Ontario tour, the team played a two-game exhibition series in February 1951 in Thunder Bay. They returned to the city for another tournament in July of that year and met Maurice “the Rocket” Richard, who refereed one of the games.

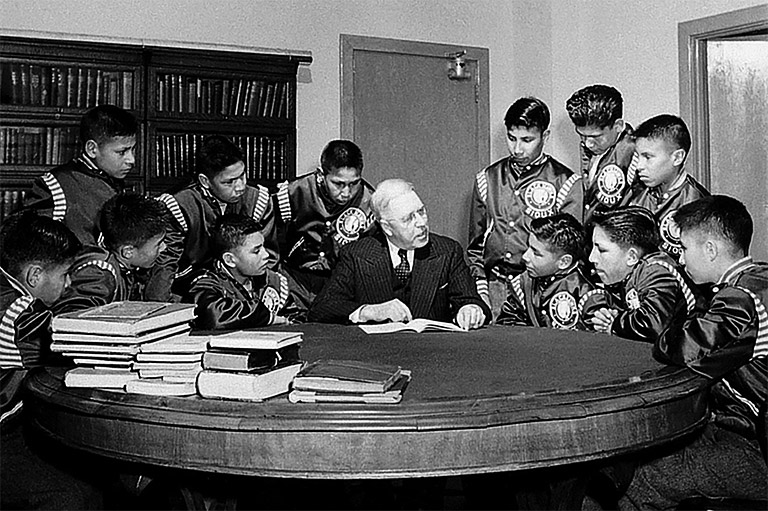

While the 1951 whirlwind hockey tour to Ottawa and Toronto was unique, the desire of residential school administrators to show off the results of their schooling program was not. Since the beginning of the residential school system, photographs of students supposedly transformed from a state of “savagery” to one of civilization appeared in missionary newsletters, government reports and exhibits, and other outlets. Sometimes, this transformation was presented as a before-and-after set of two photos. One showed the before with an Indigenous child or children in traditional clothing, and one showed the after, with the same child or children with short hair, dressed in Euro-Canadian clothing. The after image often had props, such as books or musical instruments, that suggested the schools were preparing Indigenous children for modern Canadian life. Another type of photograph that implied an uncivilized before and civilized after showed older Indigenous people in traditional clothing posed next to Indigenous children, possibly their children or grandchildren, dressed in Euro-Canadian clothing. These photos implied that, even if the older generation could not be assimilated, the younger generation could.

The set of photos Lunney took of the Black Hawks’ tour recalls the long history of before-and-after photographs that advertised the success of the government’s assimilation policies. One of the photos shows the boys looking at a totem pole in a museum while Eisenhardt appears to be teaching them about it. It is easy to imagine the totem pole in the background as the before and the boys in their Euro-Canadian hockey uniforms as the after. This image, like the other photos Lunney took on behalf of the NFBSPD, created the impression that the boys were preparing to take their places not as Cree, Oji-Cree, or Ojibway people but as future Canadian citizens under the steady guidance and care of the residential school system, the Anglican Church, and the federal government.

“Sports was my escape. I ran from all the negative.”

— Kelly Bull

Conforming to a Canadian identity

In the early 1950s, many Canadians longed for stability and unity after the Second World War. The NFBSPD projected an image of a unified, harmonious, multicultural society through its photography. It also focused on the country’s children as both innocent and in need of the care and guidance of the government. In terms of Indigenous peoples specifically, NFBSPD photographs were often intended to give the message that the Canadian government was carefully tending to their needs. During this period, the NFBSPD also favoured photographs that suggested the children of the country would be able to tackle the challenges of a modernizing Canada. These themes are apparent in the photographs Lunney took of the Black Hawks. In Lunney’s images, the team members seem to represent the government’s aspirations for the future of Indigenous people. The boys appear to be happy, healthy, and eager to be playing Canada’s game, like so many other boys across the country. That the Black Hawks were learning to be Canadian is emphasized by the images that show them at important Canadian sites, such as the Parliament Buildings and the National Archives. The boys are posed in the photographs in a manner that suggests they are literally learning from the government representative who is with them. In a photo taken in the National Archives, a man — probably Dominion archivist W. Kaye Lamb — explains a passage from a book as the team attentively looks on.

It is disturbing to consider that the Black Hawks’ Southern Ontario tour showcasing the supposedly positive effects of the school’s hockey program occurred against a backdrop of deprivation. In the photographs the boys appear to be well taken care of — with fresh haircuts and shiny new jackets — and undergoing a once-in-a-lifetime experience that would make other Canadian boys envious. In reality, all three of the former players with whom we spoke were being neglected and abused to varying degrees. Even the jackets were something of an illusion. “They never used to buy us new things,” David Wesley said. “I don’t know where they got those jackets.”

Chris Cromarty recalled being knocked unconscious by the school’s principal for speaking a single word in Ojibway. When playing hockey, he recalled, “we forgot a lot of things that were miserable about being in the residential school.” Bull was abused by multiple individuals at the school. Wesley explained that “sometimes the [bad memories] want to come back, and I’ve gotta rebuke [them].”

After graduation, Bull became a strong advocate for sports and recreation in Indigenous communities. He worked as recreation director for Grand Council Treaty Nine and was one of the founders of the North American Indigenous Games. Cromarty worked in the health field and, in the 1990s, became the first board chair of the amalgamated Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre. Wesley went on to play amateur hockey for the Port Arthur North Stars and the Port Arthur Bearcats. Although a severe head injury dashed his dreams of playing professionally, hockey continued to be part of his life. He was closely involved in building a hockey arena in Cochenour, Ontario, near where he worked as the Cochenour-Willans Gold Mine’s Native employment coordinator.

Today Wesley finds comfort in his strong Christian faith and purpose in preaching the principles of mino-bimaadiziwin, often translated from Ojibway as “living a good life.” Hockey was an escape from a school life that was so difficult, it took years for the former players to be able to speak about it. As Bull stated, “I must have … been strong to endure.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement