Nunavut’s Unfulfilled Promise

When the territory of Nunavut was founded in 1999, it promised to be a place where Inuit language and culture would not only survive but flourish. Elected the territory’s first premier on March 5 of that year, Inuk lawyer Paul Okalik modestly commented, “I want to give more opportunities to the communities.” Governor General Romeo LeBlanc was more effusive as he unveiled the Nunavut flag and coat of arms at a festive ceremony in the territory’s capital of Iqaluit a month later, on April 1. “These symbols recognize not only a new territory but an ancient heritage,” he said. “Your own spirit was always your main resource. But today your history is entering a new stage.”

This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the creation of Nunavut, and the people of the territory — now numbering nearly forty thousand — can be proud of their many accomplishments. But one important aspiration of Nunavut remains unfulfilled: to educate children, from kindergarten to the end of high school, in the native language of the Inuit. Although eighty-four per cent of the people in the territory are Inuit — and sixty-three per cent speak Inuktitut or the related language of Inuinnaqtun as their mother tongue — overwhelmingly, after the first few years of elementary school, the language of instruction in Nunavut is English.

In 2021, the Inuit political organization Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI) — along with two Inuit mothers, Bernice Tujjaaqtuqaq Clarke and Lily Anne Maniapik — launched a lawsuit in an effort to force the government of Nunavut to offer education in the Inuit language from kindergarten to grade twelve. (The author of this article, John Bainbridge, worked for NTI as a senior policy advisor before his retirement.)

In the lawsuit — which is still before the Nunavut Court of Justice — Clarke, Maniapik, and NTI allege that Nunavut’s government is discriminating against Inuit under section 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which guarantees that every individual “is equal before and under the law.”

The plaintiffs argue that Inuit are not equal with French- and English-speaking Canadians if they cannot go to school in their own language in a territory where they are in the majority. The current school system, they maintain, harms Inuit students by “undermining [their] ability to achieve their educational potential, and perpetuating historical disadvantages,” and they claim that it harms the Inuit as a people by damaging “their sense of individual and collective identity, cultural vitality, and belonging as Inuit of Nunavut.”

article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

In its defence, the government of Nunavut points out that it is elected by the people of Nunavut and consists in large majority of Inuit MLAs. It argues that section 15 of the Charter does not apply to languages taught in schools, and that its own plan to phase in Inuit language instruction in the upper grades over the next decade-and-a-half is more realistic, given “a limited pool of available, qualified Inuit language-speaking teachers and a lack of standardized Inuit language vocabulary, especially for technical subjects.”

But this approach to Inuit-language schooling may not be enough to ensure the transmission of Inuit culture and tradition to the next generation. The lawsuit makes this clear with the example of Clarke and her daughter, Alethea, who has been raised speaking Inuktitut as her mother tongue and was ten years old when the lawsuit was filed:

“Ms. Clarke was born and raised in Nunavut,” the statement of claim says. “The Inuit Language forms a vital part of her connection with her Inuit culture. It allows her to connect with and better understand her family and to access and understand the deep knowledge of her Inuit family tracing back generations. ... She wants to ensure her daughter possesses, throughout her life, the same depth of connection with the Inuit Language, her family, and Inuit culture.”

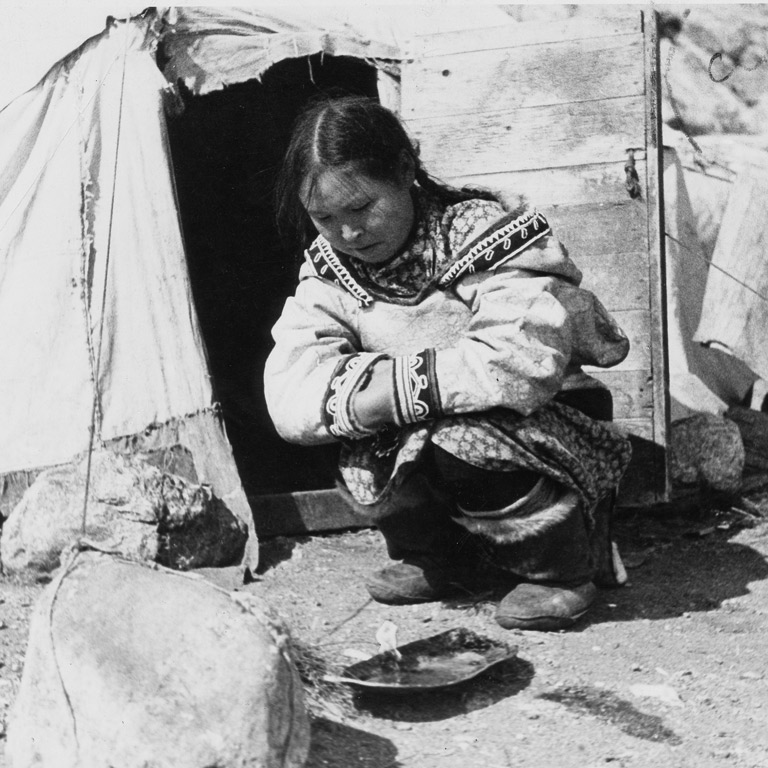

In Inuktitut, Nunavut means “our land.” It refers to the land that, for thousands of years, has been occupied by Inuit. Historically, no one owned the land; it was there for the use of every living thing. There was no estate that could be bought and sold or bequeathed to one’s children. Only the knowledge of how to live on the land could be passed on.

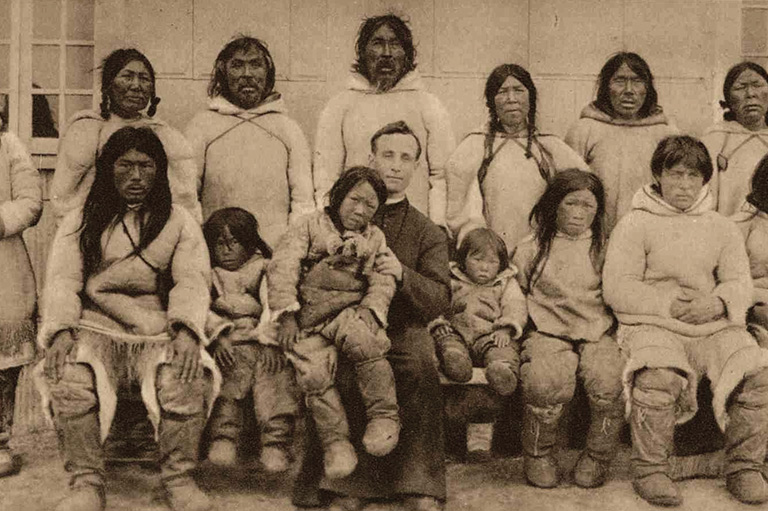

The sailor Martin Frobisher, who arrived at Baffin Island in 1576, was the first person to claim the Arctic for the British Crown, entirely without the knowledge or consent of the Inuit inhabitants. The British Crown also presumed to “grant” large parts of the Arctic to the Hudson’s Bay Company starting in 1670. However, the British didn’t follow up on their claims with serious attempts to colonize or to govern the Arctic, and until the end of the nineteenth century Inuit had mainly benign relations with European whalers, traders, and explorers.

In 1880 the British Crown transferred its claim on the Arctic to the government of Canada, and in the 1920s RCMP posts were established across the eastern Arctic, in part to bolster Canadian claims of sovereignty over the area in the face of rival claims by the United States and Denmark. Along with the RCMP came the enforcement of Canadian law. Missionaries arrived promoting alien notions of religion and insisting that Inuit cultural and spiritual beliefs must be discarded. Teachers came, and with them came a requirement to attend school in English. This, along with federal-government programs in the 1960s to build permanent villages, set in motion the destruction of the nomadic Inuit life. A new language and a foreign world view were imposed on the children. Inuit were confronted with the fact that the land they had always occupied might no longer be “our land.”

Advertisement

“We are told that we are Canadian citizens, but nobody has been able to explain how this happened,” the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (the precursor to NTI) told the Task Force on Canadian Unity in 1979. “We have never signed treaties or been conquered; we have never, in war or otherwise, surrendered our rights.”

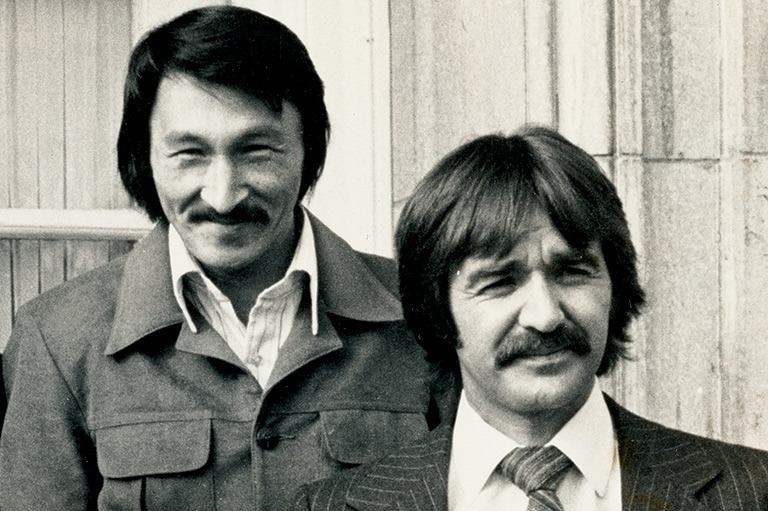

Inuit pushed back, driven by a growing sense that they were losing control of their lives, their land, and their culture. This new political awareness took concrete form in 1971 with the establishment of the Inuit Tapirisat (Inuit brotherhood) of Canada under the leadership of its first president, Tagak Curley. A charismatic Inuk from Coral Harbour in what is now Nunavut, Curley was not intimidated by white authorities, and he was moved by the belief that Inuit must keep control of the land they had occupied for thousands of years. The Canadian government was equally convinced that the land belonged to Canada and that, at best, Inuit might have some hunting and fishing rights.

“I started to think in my mind that we needed an Inuit movement, not so much for political independence but to protect our culture, language, and to exert our existence up here,” Curley told the Ottawa Citizen in a 1999 interview.

Meanwhile, in the 1970s and 1980s, Indigenous people across Canada were engaging in legal actions and seeking recognition of the concept of Aboriginal title: an ancestral territorial right predating European contact. (The Supreme Court of Canada would eventually recognize Aboriginal title in 1997.) The Inuit joined the movement, entering into land-claim negotiations with the federal government in 1976. In an April 1977 interview, Inuit negotiator John Amagoalik told CBC Radio that Inuit were seeking “a new political jurisdiction … to gain a measure of equality with French- and English-speaking Canadians.”

In 1992, after sixteen years of negotiations, Inuit of Nunavut were asked to vote on the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. This agreement with the federal government would establish, by 1999, “a new Nunavut Territory, with its own Legislative Assembly and public government,” covering about two million square kilometres. In return for surrendering Aboriginal title, Inuit secured collective ownership of eighteen per cent of the land and water in Nunavut — about 360,000 square kilometres — as well as mineral rights on about 35,000 square kilometres; a share of federal royalties from oil, gas, and mineral development on federal lands; and more than $1.1 billion in compensation. (More recently, in January 2024, the federal government transferred management of land, water, and natural-resource development to the government of Nunavut.) The agreement also addresses wildlife management and harvesting rights, parks and conservation areas, heritage resources, public-sector employment and contracting, and a range of other issues.

In November 1992, the Inuit of Nunavut voted sixty-nine per cent in favour of the agreement — and, seven years later, Nunavut became a reality.

Today, one of the greatest challenges facing Nunavut is to increase the number of Inuit in the public service, especially among teachers and school principals. While fifty-seven per cent of civil servants in Nunavut are Inuit, including forty-eight per cent of those in the Department of Education, only thirty-four per cent of teachers were Inuit as of 2022.

Far from providing full schooling in the Inuit language, the Nunavut government is focusing on the more modest goal of adding Inuit language-arts classes for all students up to grade nine by 2035 and up to grade twelve by 2039. There is no specific timeline for other subjects — like history, geography, or sciences — to be taught in the Inuit language beyond the fourth grade.

In its lawsuit, NTI is asking the Nunavut Court of Justice to rule that — within five years of the court’s decision — the government of Nunavut must offer instruction in the Inuit language across subjects to the end of high school. NTI recently won a small but significant legal victory: The Nunavut government had sought to have the case dismissed on the grounds that its constitutional arguments were invalid, leaving the plaintiffs without a legal leg to stand on. But, in March 2023, Justice Paul Bychok ruled that the case should go ahead, and, in August 2024, the Nunavut Court of Appeal upheld his decision.

“It is disappointing that Inuit must use the courts to ensure fair treatment of Inuit students, from a government created by Inuit, and that the government has used its resources to delay and stall the hearing,” said NTI president Aluki Kotierk. It remains to be seen how the courts will rule on the substance of the case — and whether this will herald a new era of language rights for Inuit and, potentially, for Indigenous people across Canada.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Timeline of Nunavut

2500 BCE

Earliest archaeological evidence of human occupation of the eastern Arctic.

1000

Inuit encounter Viking sailors along the northeast coast of North America.

1576

Inuit encounter Martin Frobisher, the first European to seek the Northwest Passage through the Arctic.

1880

Great Britain transfers its claims to the Arctic to Canada.

1920s

RCMP establishes posts in the eastern Arctic to assert Canadian sovereignty.

1971

Inuit Tapirisat of Canada is founded to assert Inuit territorial and cultural rights.

1992

Inuit and the government of Canada agree on the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement.

1999

Official creation of Nunavut Territory.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement