Home on the Plains

A tipi stands on the western prairie, its poles pointing toward the sky, its cover painted with bold designs. The tipi is a material and an architectural object — traditionally made of lodgepole pine and buffalo hides, designed to hold heat and withstand strong winds. It is also a social and a spiritual object — its interior divided into spaces to work, sleep, and pray, the painted designs on its exterior connecting its inhabitants to a celestial world.

The late Allan Pard, an Elder of the Piikani First Nation of the Niitsítapi (Blackfoot) people, believed that tipis embodied the harmony people sought between materials and life. In the past, archaeologists studied tipis mainly as physical objects; but today, multidisciplinary teams are bringing together scientific and traditional knowledge to understand the many aspects of these age-old dwellings.

Indigenous oral history, combined with new archaeological research and imagery, reveals the ingenious construction of tipis, their symbolic and spiritual significance, and how ideally suited they were to a bison-based economy of the North American grasslands.

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Why Aren’t Tipis Perfectly Symmetrical?

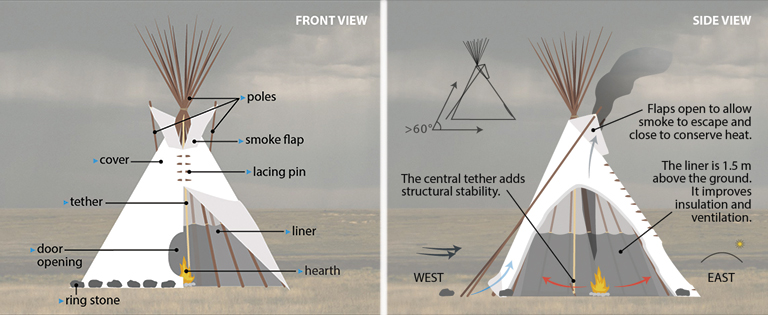

The Siouan word “tipi” is used today throughout North America to refer to a hide or fabric tent supported by a circle of wooden poles. Tipis may look symmetrical, but most tilt towards the back with a steep side that faces oncoming winds. The shallower, more sheltered side acts as a brace for structural stability and hosts the door opening, as well as an upper smoke hole with adjustable flaps on either side.

The steep side typically faces westerly winds, while the eastern doorway faces the spiritually renewing sun as it rises. Tethers are sometimes tied both inside and outside the tipi for added stability. This basic tipi design likely originated more than five thousand years ago and has persisted with minimal

How Many Bison Did It Take To Make A Tipi?

Tipi-dwelling people moved camp up to thirty times a year to track bison across the plains. Fortunately for archaeologists, many tipi perimeters were anchored by rings of large, smooth stones that were left behind when the people moved. It’s estimated that, when Europeans arrived, well over one million tipi stone circles from former camps were scattered throughout the grasslands that stretch across the present-day provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Many have since been displaced by farming and other developments.

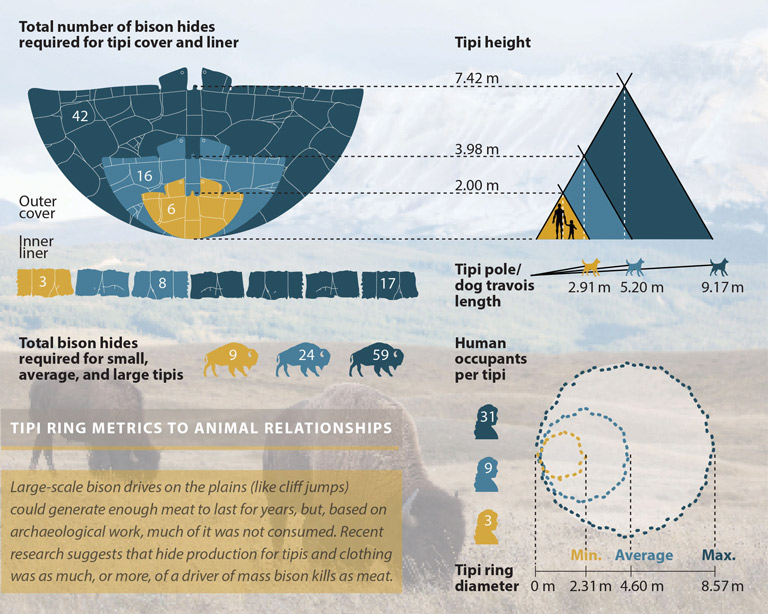

In a famous archaeological study in the 1980s, John Brumley and Barry Dau, two stalwarts of plains research, measured more than seven hundred surviving tipi rings in Alberta and detected an average ring diameter of 4.6 metres, with a minimum of 2.3 metres and a maximum of almost 9 metres. Current work on some of the fifty thousand recorded tipi rings confirms their measurements.

With ring metrics and Indigenous oral history, Jim Finnigan, a pioneering archaeologist in Saskatchewan, created statistical tables of tipi heights, showing the number of human occupants in tipis of various sizes and the number of bison hides required to cover them.

The average tipi needed a whopping twenty-four bison hides, while the largest needed almost sixty. Due to wear and tear, covers and liners needed to be replaced every year or two. For these reasons, Indigenous people — particularly women — spent hundreds of hours each year stretching, tanning, and stitching hides together.

Current research on rings across the Canadian plains reveals that the average encampment consisted of about a dozen tipis, for a total of roughly one hundred residents per camp. With twelve tipis requiring 24 hides each — 288 hides altogether — bison hunting throughout the year was likely as much of a pursuit for hides as it was for meat.

How Did Dogs Transport Tipis?

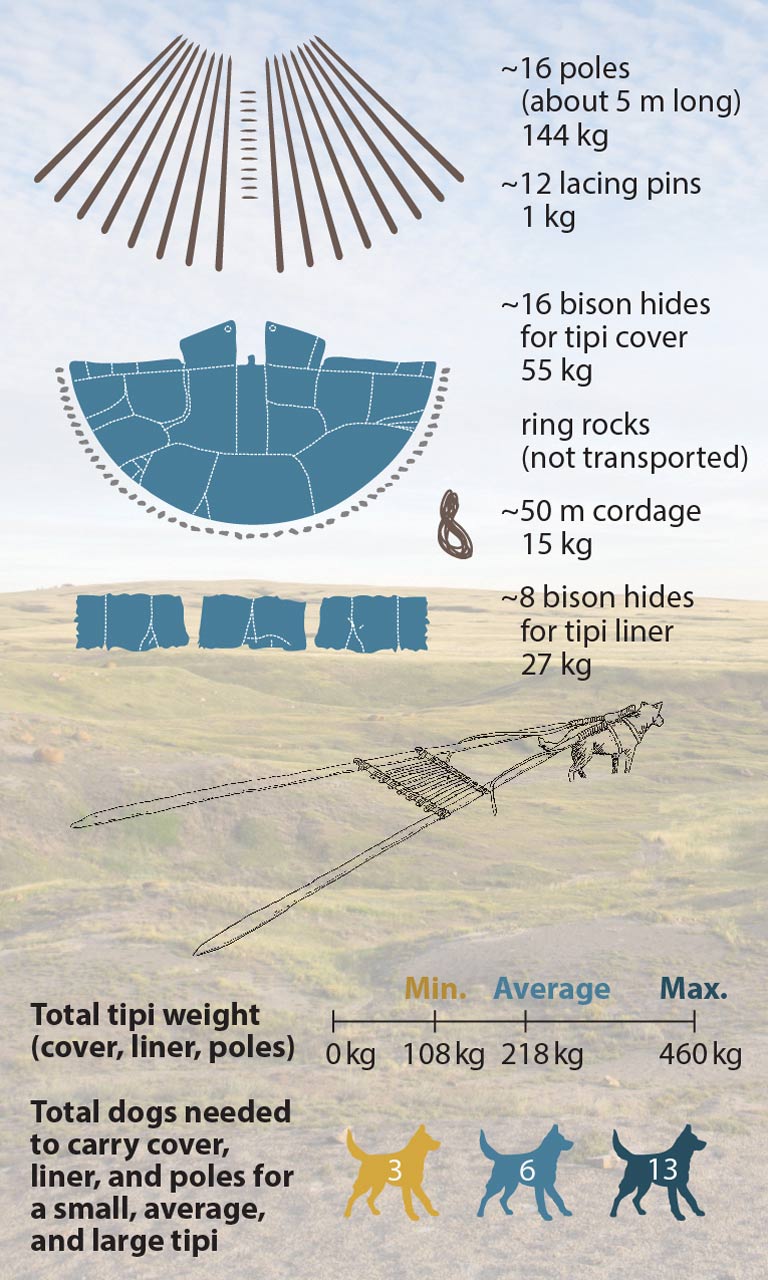

In addition to tanned hides, tipis need cordage for stitching, wooden lacing pins, and poles. Trees are rare in grassland environments, especially tall and straight ones from the appropriately named lodgepole pines, so the poles had to be carried each time people moved camp.

When poles and hides are combined, the typical tipi weighs about 220 kilograms. How did people manage to transport this enormous collective weight as they followed mobile herds of bison? Oral histories tell us that, prior to European arrival in North America, each Indigenous family had ten or more dogs whose main purpose was to transport gear. Dogs were loaded with pack saddles or wooden poles that dragged on the ground but held suspended bundles — a contraption known as manistsi to the Blackfoot and whose French name, travois, remains in common usage today. Each dog could carry about thirty-four kilograms of weight on a travois.

In fact, the Cree guide Saukamappee told map-maker David Thompson that, when searching for a name for the newly encountered horse, the Blackfoot reasoned, “as he was a slave to Man, like a dog, which carried our things, he was named Big Dog.” Although an early Blackfoot term for horse was mistatim, this word was later replaced by ponoka-mitta — a combination of elk (ponoka) and dog (imitáá).

How Did People Live Inside A Tipi?

At the University of Calgary, archaeologist Lindsay Amundsen- Meyer combines traditional and modern perspectives in a collaborative Indigenous archaeology field school, where students and Blackfoot community members excavate tipi rings and other features to interpret what life was like inside Indigenous dwellings.

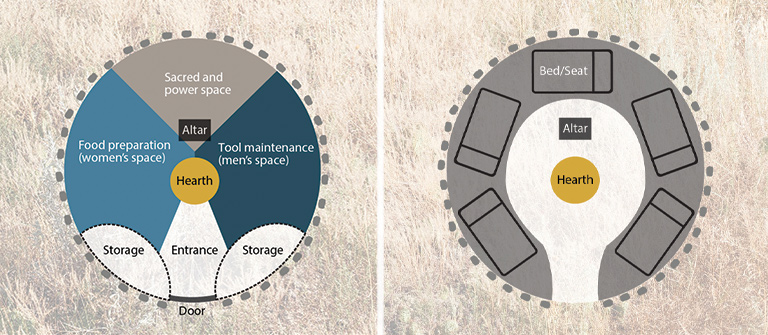

Her team works from the premise that tipi spaces are divided based on utilitarian needs, gender roles, and, just as importantly, the spirituality of space. Amundsen-Meyer and her Blackfoot partners use Indigenous oral histories, ethnographic records, and practical considerations — like how fire illuminates dwellings and how movement within a tipi affects objects on the ground — to develop models of tipi space.

When their trowels uncover charcoal and ash, it hints at a central fire; stone flakes on one side of the hearth indicate a place where men sharpened tools; pottery fragments and bits of burned bone on the other side tell stories of meals typically prepared by women. The researchers look at tipi spaces where artifacts are absent to surmise where bedding and blankets were laid and people generations ago laid down to sleep. In this way, they can deduce that people slept and performed private tasks near a tipi’s perimeter, while active and public tasks were accomplished in the inner space, near the light of the hearth.

How Do Tipis Connect Land And Sky?

Archaeology tells a practical side of the story, but hides, poles, and stones have symbolic roles, too. Indigenous Elders note that some tipi covers are elaborately painted with designs delivered through dreams and other mystical experiences. (These sacred designs should not be represented in photographs without the owners’ permission.)

Grant Many Heads of the Blackfoot says: “Tipi designs connect us with Spirit Beings in the world around us.” Earth elements, like spiritually important animals and landscapes, are drawn near the base, celestial beings or sky spirits near the top. The tipi is therefore a reflection of cosmology — Allan Pard’s harmony between the worlds outside and within.

In a balance of genders, painted tipi designs were traditionally owned by men, while the tipis themselves were the property of women. Although gender divisions are not as strict today as they once were, in the past women generally erected the tipis and maintained them, while men often selected the camp location and painted the exterior designs, which could be passed on to family or other community members through transfer ceremonies.

Tipi poles bridge the earthly world with that of the spirits above and, to the Blackfoot, serve as trails along which prayers reach the spirits. Messages to the higher world are also delivered upwards from tipi occupants through smoke and offerings from internal hearth fires and altars. To Pard, the stones of a tipi ring held bison hides in place, but also weighed down the sacred messages that tipi designs depicted, so that their blessings would remain with the land and the tipi occupants.

Over the years, most of the rings of stone that once anchored tipis to the ground have been ploughed under or trod apart by the hooves of grazing cattle. But, from those that persist on the Canadian plains, archaeologists learn why bison were hunted in such large numbers, how many families bustled around their lodges, the number of barking dogs at camp, and other general aspects of daily life in tipis. Indigenous knowledge and illustrative creativity can infuse lichen-covered rocks and archaeological statistics with meaning and, in the process, breathe life into records from the past.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Canada's History magazine was established in 1920 as The Beaver, a Journal of Progress. In its early years, the magazine focused on Canada's fur trade and life in Northern Canada. While Indigenous people were pictured in the magazine, they were rarely identified, and their stories were told by settlers. Today, Canada's History is raising the voices of First Nations, Métis and Inuit by sharing the stories of their past in their own words.

If you believe that stories of Canada’s Indigenous history should be more widely known, help us do more. Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share Indigenous stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement