One Man’s Quiet(ish) Revolution

As a natural-history writer newly arrived in Quebec, my first thought was to procure a copy of the local botany. "Marie-Victorin,” said the bookstore clerk. The name meant nothing, but the size and price of the tome he hefted made me gasp. Still, the real epiphany came when I thunked it down on the kitchen table and opened it.

In addition to the usual line drawings and technical descriptions, the exhaustive formal botany fairly hummed with ethno-botanical data, chemical properties, historical anecdotes, and literary references. As if to underscore the humanity of the work, traces of humour — a genre heresy — glimmered here and there.

I turned the pages, transfixed by the sheer magnitude of the scholarship. "Who is this guy?’’ I muttered.

Joseph Louis Conrad Kirouac was born in Quebec’s Eastern Townships in 1885, the only son of a successful merchant. A sickly and pampered boy, his tranquil bourgeois childhood offered little inkling of the swath he would cut through his people’s intellectual history. Even adolescence, with its potential for discord, saw young Conrad obediently enrolled in the Académie commerciale de Quebec, at his father’s request.

The Academie gave history its first glimpse of a man it would soon know well, for it was there that the two dominant themes of Conrad’s adult life came to the fore. One was a ravenous curiosity, tempered by scholastic discipline. The other, to his father’s heartbroken dismay, was a calling. There would be no succession to the family business, no grandson to bear the proud Kirouac name, legacy of a Breton knight. Instead, the young man would take monastic orders and live his life in a world devoid of wealth, heirs, and last names.

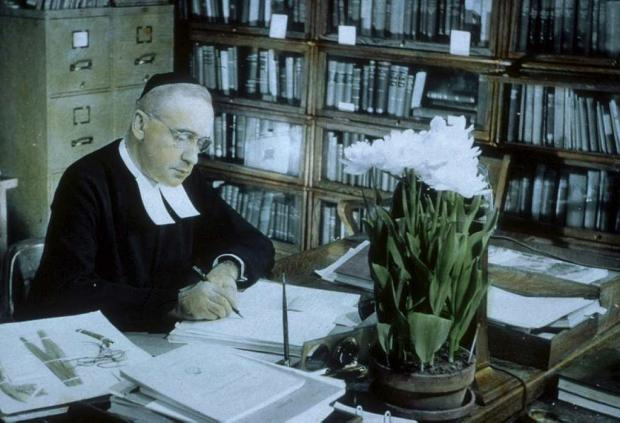

Contemporary historians tend to spin this decision as largely a practical one. The young scholar wanted to teach, a profession all but monopolized by the Church in Quebec, and so entered the Freres des Écoles chrétiennes, the same order that operated the Academic. But in fact the good brother’s calling was both deep and broad. For Marie-Victorin, as he was ordained, pursuing truth, opening minds, and questioning assumptions were primary Christian duties. His battle cry, so oft-repeated that it became a fond joke among his students, was paraphrased from Luke: Seigneur, faites que je voie! (Lord, let me see!).

The promising eighteen-year-old soon secured a teaching position in Saint-Jerôme, north of Montreal, but suffered a cruel setback when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis just months later. The Écoles chrétiennes immediately confined him to its bucolic Saint-Jerôme monastery for doctor- ordered rest. But what at first seemed a reversal soon proved the turning point in Marie-Victorin’s life, for it was there, surrounded by nature and little else, that his attention first turned to science. Armed with Flore canadienne, which passed for Quebec’s standard botany at the time, he resolved to beguile the hours by identifying all of the plants in the monastery’s forest.

The enormity of the undertaking astounded him. So many species, each precision-engineered for a specific environmental niche! Marie-Victorin soon whipped the TB, but the botany bug boiled in his veins for the rest of his life. On his release he was sent to teach in Longueuil, where he teamed up with Brother Rolland-Germain, an experienced botanist, and spent every free moment botanizing the upper St. Lawrence Valley.

Marie-Victorin’s scientific ambitions soon outstripped his self-taught skills, and in 1909 he entered correspondence study under Harvard botanist Merritt Lyndon Fernaid. His papers began appearing in professional journals around the world, and in 1914 he embarked on the daunting task of writing a comprehensive botany of Quebec. Yet his dedication to educating the general public never waned, and his regular newspaper articles on science, education, and political issues were popular breakfast-table reading for shop clerks and streetcar operators. In 1920, now a de facto scientist, Marie-Victorin founded the Institut botanique of the University of Montreal, and three years later helped to set up the Société canadienne d’histoire naturelle.

That same year, 1923, McGill botanist Francis Lloyd nominated Marie-Victorin to the biology section of the Royal Society of Canada. The all-anglophone review board refused, but relented the following year before heavy petitioning, placing Marie-Victorin in the French history and literature section-evidently judging that a more appropriate billet for a Quebecois. Only in 1927 did the Royal Society finally bow to the inevitable and grant Marie-Victorin the science appointment he so richly deserved.

But Marie-Victorin’s activities didn’t always sit well with his employers. Monks are called to selflessness and obedience, and though as a teaching order the Écoles chrétiennes were comparatively worldly, their leadership was growing increasingly uneasy with Marie-Victorin’s celebrity. He had become a pop-culture icon, his name synonymous with intelligence and erudition throughout French Canada. "He’s no Marie-Victorin," said trendy francophones of slow-witted individuals. Even more alarming, the ambitious cleric publicly advocated such anti-establishment causes as gender equity, school reform, and Quebec nationalism.

Marie-Victorin’s personal correspondence leaves little doubt of the strength of his convictions: "If there were female cardinals," he wrote to his sister, a nun and school director, "we’d see some changes in the Catholic Church." To a niece embarking on a tour of Europe, he wrote: “Don’t be shocked by the nudity you’ll see everywhere ... our education in these matters is crude." His advice to a nephew approaching ordination was shockingly apropos: “The day when the French Canadian priest... was a petty king in his rural parish, oblivious of the great noisy world, is gone. The priests of your generation will live by their wits."

Today these statements have the eerie ring of prophecy, anticipating as they do the Quiet Revolution by thirty years. His vision remains germane even in our time. He decried the plunder of Quebec by American corporations, saying it poisoned the environment and threatened Quebecois culture. He foretold the decline of the Catholic Church in Quebec in an age when it governed every thought and action. He fingered lazy, politically sanitized schools as a threat to civil liberties and economic independence. And he encouraged female students to pursue careers in science; Marcelle Gauvreau, one of the great pioneers of science education in Quebec, was a Marie-Victorin protégée and colleague.

All of this in the darkest days of la Grande Noirceur, more or less the first half of the twentieth century, when abject obedience to authority, both religious and secular, was judged key to Quebec’s cultural survival. Intellectual autonomy threatened that stratagem, and was zealously discouraged. In his 1992 book French Canadians. Michel Gratton excavates a pre-Quiet Revolution math curriculum that consisted of little more than calculating how many religious medallions a given sum of money might buy; his chapter on period schools is called "The Enemy Within." As late as 1960, Quebec’s newspapers were set ablaze by the blistering criticism of Frère Untel (later revealed to be the pseudonym of writer/journalist Jean-Paul Desbiens), who denounced Quebec’s hobbled school system, repressed intellect, and squandered potential.

Such was Marie-Victorin’s world, and his defiance of it did not amuse his superiors. The distinguished scientist was frequently ordered into periods of enforced "reflection," during which he was forbidden to publish or communicate with the media. He also took extended retreats into cloistered life, apparently by mutual consent. The paradox eloquently encapsulates the contradictions of Catholic Quebec: fellow frontline clerics, such as his sister and teaching colleagues, applauded his work, but those in the upper ranks found it threatening. And aggravating them was dangerous sport for a lowly monk, however famous.

Nor were secular authorities more kindly disposed. For example. Marie-Victorin’s campaign for a world-class botanical garden in Montreal was dogged by palace intrigue and dirty politics. Still, by banking on his unmatched name recognition, Marie-Victorin was able after a ten-year struggle to ram his Jardin botanique past nearsighted bureaucrats and Depression-era bean counters. As anti-German sentiment swelled in the late 1930s, he vociferously defended the garden’s German-born architect, Henry Teuscher, from spurious spying charges. Even after the Jardin botanique finally opened in 1938, its existence still wasn’t secure. With war on the horizon, a freshly elected anti-Marie-Victorin provincial premier leased the entire premises to the air force for one dollar. The thrust was typical, as was the parry by powerful Marie-Victorin supporters who stepped in and quashed the deal. Ultimately, they managed to get the garden transferred to municipal ownership, saving the cherished Montreal landmark from being bulldozed into a parade ground.

Marie-Victorin’s public escapades are so colourful that it’s tempting to dismiss his professional triumphs as routine or arcane. Yet, had he never come to public attention, his academic accomplishments alone would have earned him an enduring place in Canada’s pantheon. Of these, Flore laurentienne, his complete standard botany of subarctic Quebec, is certainly the greatest. Marie-Victorin laboured on this masterpiece, one of the world’s best examples of the genre, for twenty years. The final result, first issued in 1935, is breathtaking in scope and detail.

"In the Canadian countryside," we read under Arisaema atrorubens (jack-in-the-pulpit), (the rhizomes) are employed against ‘weak blood and stomach troubles’. The Iroquois give |it| the name Kah-a-hoo-sa, which means ‘Indian cradle’; there is indeed a resemblance between the spathe that envelops the long spadix and the nagane in which Indian women carry their babies.

Acorus calamus (sweet flag), we learn, was introduced to western and central Europe about 1574, when it was sent to Matthiole of Prague from Constantinople. ... In the Middle Ages, the rhizomes... were used in cathedrals as a fragrant floor covering and they are still used in perfume and to flavour beer, wine, and snuff. ... In India, sweet flag sugar is a universal remedy for infant colic.... the Chinese place Acorus (Pai-chang) at the head of the bed to repel lice.

More than a mere field guide, Flore laurentienne is a monument both to the man and the science that possessed his heart. Even the most dispassionate reader can’t help but feel the love and respect he had for his subject, and above all, his utter mastery of it.

The Jardin botanique and Flore laurentienne would have been impressive as Marie-Victorin’s only legacies, but they are just the most salient examples. Despite precarious health, he continued to teach classes, participate in international conferences, direct the University of Montreal science department and the Jardin botanique, and stump tirelessly for education reform. His article series appeared uninterrupted, and eventually won him a spot as moderator of a popular weekly CBC science program. Incredibly, while engaged in all of this, he also pursued epic expeditions through Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Caribbean. Cuba, whose warm breezes soothed Marie-Victorin’s damaged lungs, became his second home. Neglecting superiors’ orders to rest and heal, the ailing scholar botanized his way from one end of the island to the other. Shortly before his death, he received Cuba’s National Order of Merit for seminal work in Cuban botany. In a telling measure of the respect in which he was held, the Canadian monk shared the award ceremony with the Archbishop of Havana.

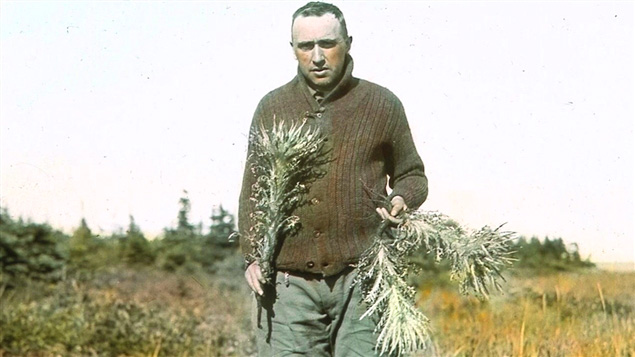

For all of his trekking and triumphs, Marie-Victorin’s end was touchingly prosaic. On July 15, 1944, he and several friends departed for Black Lake, about sixty kilometres south of Quebec City, to search for a rare fern. On the way home their car was struck head on by another. Seat belts were still twenty years in the future, and Marie-Victorin, seated beside the driver, was launched into the windshield with sufficient force to smash the glass. The head injury and broken foot were acutely painful, but not life-threatening. Still, as he lay beside the road, the bleeding monk requested a priest. "I don’t believe my heart will endure this," he explained through swollen lips.

The great scientist’s analysis proved tragically accurate. At just fifty-nine, having received the last rites from the local priest, Marie Victorin died in the back seat of a taxi en route to hospital.

Today, the venerated scholar’s memory has faded from popular consciousness in Quebec, where most inhabitants would be hard-pressed to explain the "Marie-Victorin’’ streets, schools, and parks that pepper their province. Canadians elsewhere don’t even enjoy that much information. However, to scientists and historians he remains one of the truly great Canadians, masterful and modest, a scholar who enhanced the international prestige of his young nation and profoundly changed the intellectual landscape of his society. Quebec’s world-renowned university science departments owe their existence to Marie-Victorin, as does the eminently Canadian figure of the populist scientist. Product of a bygone, jarringly different society, his groundbreaking career nevertheless laid the foundations for that which we most value today.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement